полная версия

полная версияThe Major Operations of the Navies in the War of American Independence

With the destruction of the flotilla ends the naval story of the Lakes during the War of the American Revolution. Satisfied that it was too late to proceed against Ticonderoga that year, Carleton withdrew to St. John's and went into winter-quarters. The following year the enterprise was resumed under General Burgoyne; but Sir William Howe, instead of coöperating by an advance up the Hudson, which was the plan of 1776, carried his army to Chesapeake Bay, to act thence against Philadelphia. Burgoyne took Ticonderoga and forced his way as far as Saratoga, sixty miles from Ticonderoga and thirty from Albany, where Howe should have met him. There he was brought to a stand by the army which the Americans had collected, found himself unable to advance or to retreat, and was forced to lay down his arms on October 17th, 1777. The garrison left by him at Ticonderoga and Crown Point retired to Canada, and the posts were re-occupied by the Americans. No further contest took place on the Lake, though the British vessels remained in control of it, and showed themselves from time to time up to 1781. With the outbreak of war between Great Britain and France, in 1778, the scene of maritime interest shifted to salt water, and there remained till the end.

CHAPTER II

NAVAL ACTION AT BOSTON, CHARLESTON, NEW YORK, AND NARRAGANSETT BAY—ASSOCIATED LAND OPERATIONS UP TO THE BATTLE OF TRENTON

1776

The opening conflict between Great Britain and her North American Colonies teaches clearly the necessity, too rarely recognised in practice, that when a State has decided to use force, the force provided should be adequate from the first. This applies with equal weight to national policies when it is the intention of the nation to maintain them at all costs. The Monroe Doctrine for instance is such a policy; but unless constant adequate preparation is maintained also, the policy itself is but a vain form of words. It is in preparation beforehand, chiefly if not uniformly, that the United States has failed. It is better to be much too strong than a little too weak. Seeing the evident temper of the Massachusetts Colonists, force would be needed to execute the Boston Port Bill and its companion measures of 1774; for the Port Bill especially, naval force. The supplies for 1775 granted only 18,000 seamen,—2000 less than for the previous year. For 1776, 28,000 seamen were voted, and the total appropriations rose from £5,556,000 to £10,154,000; but it was then too late. Boston was evacuated by the British army, 8000 strong on the 17th of March, 1776; but already, for more than half a year, the spreading spirit of revolt in the thirteen Colonies had been encouraged by the sight of the British army cooped up in the town, suffering from want of necessaries, while the colonial army blockading it was able to maintain its position, because ships laden with stores for the one were captured, and the cargoes diverted to the use of the other. To secure free and ample communications for one's self, and to interrupt those of the opponent, are among the first requirements of war. To carry out the measures of the British government a naval force was needed, which not only should protect the approach of its own transports to Boston Bay, but should prevent access to all coast ports whence supplies could be carried to the blockading army. So far from this, the squadron was not equal, in either number or quality, to the work to be done about Boston; and it was not until October, 1775, that the Admiral was authorized to capture colonial merchant vessels, which therefore went and came unmolested, outside of Boston, carrying often provisions which found their way to Washington's army.

After evacuating Boston, General Howe retired to Halifax, there to await the coming of reinforcements, both military and naval, and of his brother, Vice-Admiral Lord Howe, appointed to command the North American Station. General Howe was commander-in-chief of the forces throughout the territory extending from Nova Scotia to West Florida; from Halifax to Pensacola. The first operation of the campaign was to be the reduction of New York.

The British government, however, had several objects in view, and permitted itself to be distracted from the single-minded prosecution of one great undertaking to other subsidiary operations, not always concentric. Whether the control of the line of the Hudson and Lake Champlain ought to have been sought through operations beginning at both ends, is open to argument; the facts that the Americans were back in Crown Point in the beginning of July, 1776, and that Carleton's 13,000 men got no farther than St. John's that year, suggest that the greater part of the latter force would have been better employed in New York and New Jersey than about Champlain. However that may be, the diversion to the Carolinas of a third body, respectable in point of numbers, is scarcely to be defended on military grounds. The government was induced to it by the expectation of local support from royalists. That there were many of these in both Carolinas is certain; but while military operations must take account of political conditions, the latter should not be allowed to overbalance elementary principles of the military art. It is said that General Howe disapproved of this ex-centric movement.

The force destined for the Southern coasts assembled at Cork towards the end of 1775, and sailed thence in January, 1776. The troops were commanded by Lord Cornwallis, the squadron by Nelson's early patron, Commodore Sir Peter Parker, whose broad pennant was hoisted on board the Bristol, 50. After a boisterous passage, the expedition arrived in May off Cape Fear in North Carolina, where it was joined by two thousand men under Sir Henry Clinton, Cornwallis's senior, whom Howe by the government's orders had detached to the southward in January. Upon Clinton's appearance, the royalists in North Carolina had risen, headed by the husband of Flora Macdonald, whose name thirty years before had been associated romantically with the escape of the young Pretender from Scotland. She had afterwards emigrated to America. The rising, however, had been put down, and Clinton had not thought it expedient to try a serious invasion, in face of the large force assembled to resist him. Upon Parker's coming, it was decided to make an attempt upon Charleston, South Carolina. The fleet therefore sailed from Cape Fear on the 1st of June, and on the 4th anchored off Charleston Bar.

Charleston Harbour opens between two of the sea-islands which fringe the coasts of South Carolina and Georgia. On the north is Sullivan's Island, on the south James Island. The bar of the main entrance was not abreast the mouth of the port, but some distance south of it. Inside the bar, the channel turned to the northward, and thence led near Sullivan's Island, the southern end of which was therefore chosen as the site of the rude fort hastily thrown up to meet this attack, and afterwards called Fort Moultrie, from the name of the commander. From these conditions, a southerly wind was needed to bring ships into action. After sounding and buoying the bar, the transports and frigates crossed on the 7th and anchored inside; but as it was necessary to remove some of the Bristol's guns, she could not follow until the 10th. On the 9th Clinton had landed in person with five hundred men, and by the 15th all the troops had disembarked upon Long Island, next north of Sullivan's. It was understood that the inlet between the two was fordable, allowing the troops to coöperate with the naval attack, by diversion or otherwise; but this proved to be a mistake. The passage was seven feet deep at low water, and there were no means for crossing; consequently a small American detachment in the scrub wood of the island sufficed to check any movement in that quarter. The fighting therefore was confined to the cannonading of the fort by the ships.

Circumstances not fully explained caused the attack to be fixed for the 23d; an inopportune delay, during which Americans were strengthening their still very imperfect defences. On the 23d the wind was unfavourable. On the 25th the Experiment, 50, arrived, crossed the bar, and, after taking in her guns again, was ready to join in the assault. On the 27th, at 10 A.M., the ships got under way with a south-east breeze, but this shifted soon afterwards to north-west, and they had to anchor again, about a mile nearer to Sullivan's Island. On the following day the wind served, and the attack was made.

In plan, Fort Moultrie was square, with a bastion at each angle. In construction, the sides were palmetto logs, dovetailed and bolted together, laid in parallel rows, sixteen feet apart; the interspace being filled with sand. At the time of the engagement, the south and west fronts were finished; the other fronts were only seven feet high, but surmounted by thick planks, to be tenable against escalade. Thirty-one guns were in place, 18 and 9-pounders, of which twenty-one were on the south face, commanding the channel. Within was a traverse running east and west, protecting the gunners from shots from the rear; but there was no such cover against enfilading fire, in case an enemy's ship passed the fort and anchored above it. "The general opinion before the action," Moultrie says, "and especially among sailors, was that two frigates would be sufficient to knock the town about our ears, notwithstanding our batteries." Parker may have shared this impression, and it may account for his leisureliness. When the action began, the garrison had but twenty-eight rounds for each of twenty-six cannon, but this deficiency was unknown to the British.

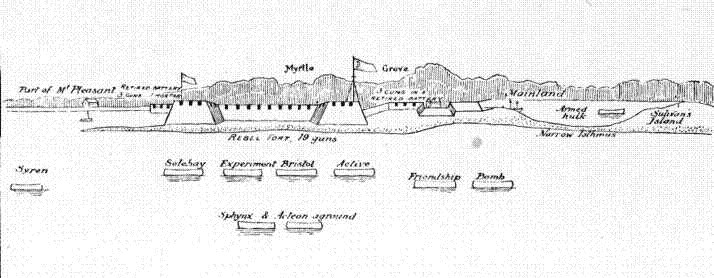

Attack on Fort Moultrie in 1776

Parker's plan was that the two 50's, Bristol and Experiment, and two 28-gun frigates, the Active and the Solebay, should engage the main front; while two frigates of the same class, the Actæon and the Syren, with a 20-gun corvette, the Sphinx, should pass the fort, anchoring to the westward, up-channel, to protect the heavy vessels against fire-ships, as well as to enfilade the principal American battery. The main attack was to be further supported by a bomb-vessel, the Thunder, accompanied by the armed transport Friendship, which were to take station to the southeast of the east bastion of the engaged front of the fort. The order to weigh was given at 10.30 A.M., when the flood-tide had fairly made; and at 11.15 the Active, Bristol, Experiment, and Solebay, anchored in line ahead, in the order named, the Active to the eastward. These ships seem to have taken their places skilfully without confusion, and their fire, which opened at once, was rapid, well-sustained, and well-directed; but their position suffered under the radical defect that, whether from actual lack of water, or only from fear of grounding, they were too far from the works to use grape effectively. The sides of ships being much weaker than those of shore works, while their guns were much more numerous, the secret of success was to get near enough to beat down the hostile fire by a multitude of projectiles. The bomb-vessel Thunder anchored in the situation assigned her; but her shells, though well aimed, were ineffective. "Most of them fell within the fort," Moultrie reported, "but we had a morass in the middle, which swallowed them instantly, and those that fell in the sand were immediately buried." During the action the mortar bed broke, disabling the piece.

Owing to the scarcity of ammunition in the fort, the garrison had positive orders not to engage at ranges exceeding four hundred yards. Four or five shots were thrown at the Active, while still under sail, but with this exception the fort kept silence until the ships anchored, at a distance estimated by the Americans to be three hundred and fifty yards. The word was then passed along the platform, "Mind the Commodore; mind the two 50-gun ships,"—an order which was strictly obeyed, as the losses show. The protection of the work proved to be almost perfect,—a fact which doubtless contributed to the coolness and precision of fire vitally essential with such deficient resources. The texture of the palmetto wood suffered the balls to sink smoothly into it without splintering, so that the facing of the work held well. At times, when three or four broadsides struck together, the merlons shook so that Moultrie feared they would come bodily in; but they withstood, and the small loss inflicted was chiefly through the embrasures. The flagstaff being shot away, falling outside into the ditch, a young sergeant, named Jasper, distinguished himself by jumping after it, fetching back and rehoisting the colours under a heavy fire.

In the squadron an equal gallantry was shown under circumstances which made severe demands upon endurance. Whatever Parker's estimate of the worth of the defences, no trace of vain-confidence appears in his dispositions, which were thorough and careful, as the execution of the main attack was skilful and vigorous; but the ships' companies, expecting an easy victory, had found themselves confronted with a resistance and a punishment as severe as were endured by the leading ships at Trafalgar, and far more prolonged. Such conditions impose upon men's tenacity the additional test of surprise and discomfiture. The Experiment, though very small for a ship of the line, lost 23 killed and 56 wounded, out of a total probably not much exceeding 300; while the Bristol, having the spring shot away, swung with her head to the southward and her stern to the fort, undergoing for a long time a raking fire to which she could make little reply. Three several attempts to replace the spring were made by Mr. James Saumarez,—afterwards the distinguished admiral, Lord de Saumarez, then a midshipman,—before the ship was relieved from this grave disadvantage. Her loss was 40 killed and 71 wounded; not a man escaping of those stationed on the quarter-deck at the beginning of the action. Among the injured was the Commodore himself, whose cool heroism must have been singularly conspicuous, from the notice it attracted in a service where such bearing was not rare. At one time when the quarter-deck was cleared and he stood alone upon the poop-ladder, Saumarez suggested to him to come down; but he replied, smiling, "You want to get rid of me, do you?" and refused to move. The captain of the ship, John Morris, was mortally wounded. With commendable modesty Parker only reported himself as slightly bruised; but deserters stated that for some days he needed the assistance of two men to walk, and that his trousers had been torn off him by shot or splinters. The loss in the other ships was only one killed, 14 wounded. The Americans had 37 killed and wounded.

The three vessels assigned to enfilade the main front of the fort did not get into position. They ran on the middle ground, owing, Parker reported, to the ignorance of the pilots. Two had fouled each other before striking. Having taken the bottom on a rising tide, two floated in a few hours, and retreated; but the third, the Actæon, 28, sticking fast, was set on fire and abandoned by her officers. Before she blew up, the Americans boarded her, securing her colours, bell, and some other trophies. "Had these ships effected their purpose," Moultrie reported, "they would have driven us from our guns."

The main division held its ground until long after nightfall, firing much of the time, but stopping at intervals. After two hours it had been noted that the fort replied very slowly, which was attributed to its being overborne, instead of to the real cause, the necessity for sparing ammunition. For the same reason it was entirely silent from 3.30 P.M. to 6, when fire was resumed from only two or three guns, whence Parker surmised that the rest had been dismounted. The Americans were restrained throughout the engagement by the fear of exhausting entirely their scanty store.

"About 9 P.M.," Parker reported, "being very dark, great part of our ammunition expended, the people fatigued, the tide of ebb almost done, no prospect from the eastward (that is, from the army), and no possibility of our being of any further service, I ordered the ships to withdraw to their former moorings." Besides the casualties among the crew, and severe damage to the hull, the Bristol's mainmast, with nine cannon-balls in it, had to be shortened, while the mizzen-mast was condemned. The injury to the frigates was immaterial, owing to the garrison's neglecting them.

The fight in Charleston Harbour, the first serious contest in which ships took part in this war, resembles generically the battle of Bunker's Hill, with which the regular land warfare had opened a year before. Both illustrate the difficulty and danger of a front attack, without cover, upon a fortified position, and the advantage conferred even upon untrained men, if naturally cool, resolute, and intelligent, not only by the protection of a work, but also, it may be urged, by the recognition of a tangible line up to which to hold, and to abandon which means defeat, dishonour, and disaster. It is much for untried men to recognise in their surroundings something which gives the unity of a common purpose, and thus the coherence which discipline imparts. Although there was in Parker's dispositions nothing open to serious criticism,—nothing that can be ascribed to undervaluing his opponent,—and although, also, he had good reason to expect from the army active coöperation which he did not get, it is probable that he was very much surprised, not only at the tenacity of the Americans' resistance, but at the efficacy of their fire. He felt, doubtless, the traditional and natural distrust—and, for the most part, the justified distrust—with which experience and practice regard inexperience. Some seamen of American birth, who had been serving in the Bristol, deserted after the fight. They reported that her crew said, "We were told the Yankees would not stand two fires, but we never saw better fellows;" and when the fire of the fort slackened and some cried, "They have done fighting," others replied, "By God, we are glad of it, for we never had such a drubbing in our lives." "All the common men of the fleet spoke loudly in praise of the garrison,"—a note of admiration so frequent in generous enemies that we may be assured that it was echoed on the quarter-deck also. They could afford it well, for there was no stain upon their own record beyond the natural mortification of defeat; no flinching under the severity of their losses, although a number of their men were comparatively raw, volunteers from the transports, whose crews had come forward almost as one man when they knew that the complements of the ships were short through sickness. Edmund Burke, a friend to both sides, was justified in saying that "never did British valour shine more conspicuously, nor did our ships in an engagement of the same nature experience so serious an encounter." There were several death-vacancies for lieutenants; and, as the battle of Lake Champlain gave Pellew his first commission, so did that of Charleston Harbour give his to Saumarez, who was made lieutenant of the Bristol by Parker. Two years later, when the ship had gone to Jamaica, he was followed on her quarter-deck by Nelson and Collingwood, who also received promotion in her from the same hand.

The attack on Fort Moultrie was not resumed. After necessary repairs, the ships of war with the troops went to New York, where they arrived on the 4th of August, and took part in the operations for the reduction of that place under the direction of the two Howes.

The occupation of New York Harbour, and the capture of the city were the most conspicuous British successes of the summer and fall of 1776. While Parker and Clinton were meeting with defeat at Charleston, and Arnold was hurrying the preparation of his flotilla on Champlain, the two brothers, General Sir William Howe and the Admiral, Lord Howe, were arriving in New York Bay, invested not only with the powers proper to the commanders of great fleets and armies, but also with authority as peace commissioners, to negotiate an amicable arrangement with the revolted Colonies.

Sir William Howe had awaited for some time at Halifax the arrival of the expected reinforcements, but wearying at last he sailed thence on the 10th of June, 1776, with the army then in hand. On the 25th he himself reached Sandy Hook, the entrance to New York Bay, having preceded the transports in a frigate. On the 29th, the day after Parker's repulse at Fort Moultrie, the troops arrived; and on July 3d, the date on which Arnold, retreating from Canada, reached Crown Point, the British landed on Staten Island, which is on the west side of the lower Bay. On the 12th came in the Eagle, 64, carrying the flag of Lord Howe. This officer was much esteemed by the Americans for his own personal qualities, and for his attitude towards them in the present dispute, as well as for the memory of his brother, who had endeared himself greatly to them in the campaign of 1758, when he had fallen near Lake Champlain; but the decisive step of declaring their independence had been taken already, on July 4th, eight days before the Admiral's arrival. A month was spent in fruitless attempts to negotiate with the new government, without recognising any official character in its representatives. During that time, however, while abstaining from decisive operations, cruisers were kept at sea to intercept American traders, and the Admiral, immediately upon arriving, sent four vessels of war twenty-five miles up the Hudson River, as far as Tarrytown. This squadron was commanded by Hyde Parker, afterwards, in 1801, Nelson's commander-in-chief at Copenhagen. The service was performed under a tremendous cannonade from all the batteries on both shores, but the ships could not be stopped. Towards the middle of August it was evident that the Americans would not accept any terms in the power of the Howes to offer, and it became necessary to attempt coercion by arms.

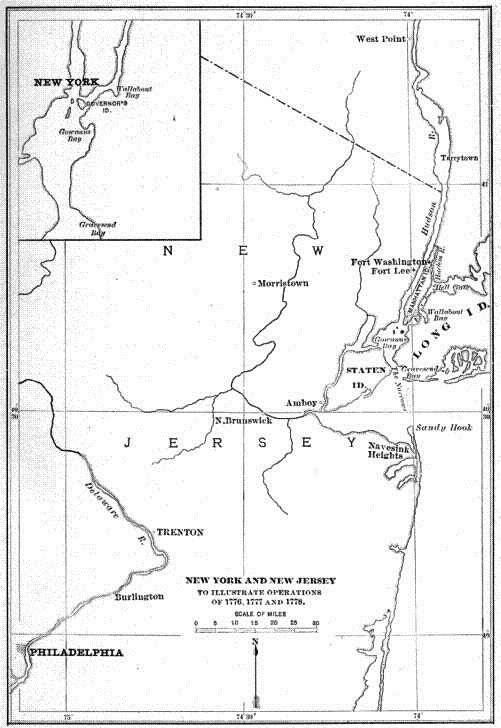

New York and New Jersey: to illustrate Operations of 1776, 1777, and 1778

In the reduction of New York in 1776, the part played by the British Navy, owing to the nature of the campaign in general and of the enemy's force in particular, was of that inconspicuous character which obscures the fact that without the Navy the operations could not have been undertaken at all, and that the Navy played to them the part of the base of operations and line of communications. Like the foundations of a building, these lie outside the range of superficial attention, and therefore are less generally appreciated than the brilliant fighting going on at the front, to the maintenance of which they are all the time indispensable. Consequently, whatever of interest may attach to any, or to all, of the minor affairs, which in the aggregate constitute the action of the naval force in such circumstances, the historian of the major operations is confined perforce to indicating the broad general effect of naval power upon the issue. This will be best done by tracing in outline the scene of action, the combined movements, and the Navy's influence in both.

The harbour of New York divides into two parts—the upper and lower Bays—connected by a passage called the Narrows, between Long and Staten Islands, upon the latter of which the British troops were encamped. Long Island, which forms the eastern shore of the Narrows, extends to the east-north-east a hundred and ten miles, enclosing between itself and the continent a broad sheet of water called Long Island Sound, that reaches nearly to Narragansett Bay. The latter, being a fine anchorage, entered also into the British scheme of operations, as an essential feature in a coastwise maritime campaign. Long Island Sound and the upper Bay of New York are connected by a crooked and difficult passage, known as the East River, eight or ten miles in length, and at that time nearly a mile wide15 abreast the city of New York. At the point where the East River joins New York Bay, the Hudson River, an estuary there nearly two miles wide, also enters from the north,—a circumstance which has procured for it the alternative name of the North River. Near their confluence is Governor's Island, half a mile below the town, centrally situated to command the entrances to both. Between the East and North rivers, with their general directions from north and east-north-east, is embraced a long strip of land gradually narrowing to the southward. The end of this peninsula, as it would otherwise be, is converted into an island, of a mean length of about eight miles, by the Harlem River,—a narrow and partially navigable stream connecting the East and North rivers. To the southern extreme of this island, called Manhattan, the city of New York was then confined.