Полная версия

She: A History of Adventure

“There,” he said, “I must go, you have the chest, and my will will be found among my papers, under the authority of which the child will be handed over to you. You will be well paid, Holly, and I know that you are honest, but if you betray my trust, by Heaven, I will haunt you.”

I said nothing, being, indeed, too bewildered to speak.

He held up the candle, and looked at his own face in the glass. It had been a beautiful face, but disease had wrecked it. “Food for the worms,” he said. “Curious to think that in a few hours I shall be stiff and cold – the journey done, the little game played out. Ah me, Holly! life is not worth the trouble of life, except when one is in love – at least, mine has not been; but the boy Leo’s may be if he has the courage and the faith. Good-bye, my friend!” and with a sudden access of tenderness he flung his arm about me and kissed me on the forehead, and then turned to go.

“Look here, Vincey,” I said, “if you are as ill as you think, you had better let me fetch a doctor.”

“No, no,” he said earnestly. “Promise me that you won’t. I am going to die, and, like a poisoned rat, I wish to die alone.”

“I don’t believe that you are going to do anything of the sort,” I answered. He smiled, and, with the word “Remember” on his lips, was gone. As for myself, I sat down and rubbed my eyes, wondering if I had been asleep. As this supposition would not bear investigation I gave it up and began to think that Vincey must have been drinking. I knew that he was, and had been, very ill, but still it seemed impossible that he could be in such a condition as to be able to know for certain that he would not outlive the night. Had he been so near dissolution surely he would scarcely have been able to walk, and carry a heavy iron box with him. The whole story, on reflection, seemed to me utterly incredible, for I was not then old enough to be aware how many things happen in this world that the common sense of the average man would set down as so improbable as to be absolutely impossible. This is a fact that I have only recently mastered. Was it likely that a man would have a son five years of age whom he had never seen since he was a tiny infant? No. Was it likely that he could foretell his own death so accurately? No. Was it likely that he could trace his pedigree for more than three centuries before Christ, or that he would suddenly confide the absolute guardianship of his child, and leave half his fortune, to a college friend? Most certainly not. Clearly Vincey was either drunk or mad. That being so, what did it mean? and what was in the sealed iron chest?

The whole thing baffled and puzzled me to such an extent that at last I could stand it no longer, and determined to sleep over it. So I jumped up, and having put the keys and the letter that Vincey had left away into my despatch-box, and stowed the iron chest in a large portmanteau, I turned in, and was soon fast asleep.

As it seemed to me, I had only been asleep for a few minutes when I was awakened by somebody calling me. I sat up and rubbed my eyes; it was broad daylight – eight o’clock, in fact.

“Why, what is the matter with you, John?” I asked of the gyp who waited on Vincey and myself. “You look as though you had seen a ghost!”

“Yes, sir, and so I have,” he answered, “leastways I’ve seen a corpse, which is worse. I’ve been in to call Mr. Vincey, as usual, and there he lies stark and dead!”

II

THe Years Roll By

As might be expected, poor Vincey’s sudden death created a great stir in the College; but, as he was known to be very ill, and a satisfactory doctor’s certificate was forthcoming, there was no inquest. They were not so particular about inquests in those days as they are now; indeed, they were generally disliked, because of the scandal. Under all these circumstances, being asked no questions, I did not feel called upon to volunteer any information about our interview on the night of Vinc-ey’s decease, beyond saying that he had come into my rooms to see me, as he often did. On the day of the funeral a lawyer came down from London and followed my poor friend’s remains to the grave, and then went back with his papers and effects, except, of course, the iron chest which had been left in my keeping. For a week after this I heard no more of the matter, and, indeed, my attention was amply occupied in other ways, for I was up for my Fellowship, a fact that had prevented me from attending the funeral or seeing the lawyer. At last, however, the examination was over, and I came back to my rooms and sank into an easy chair with a happy consciousness that I had got through it very fairly.

Soon, however, my thoughts, relieved of the pressure that had crushed them into a single groove during the last few days, turned to the events of the night of poor Vincey’s death, and again I asked myself what it all meant, and wondered if I should hear anything more of the matter, and if I did not, what it would be my duty to do with the curious iron chest. I sat there and thought and thought till I began to grow quite disturbed over the whole occurrence: the mysterious midnight visit, the prophecy of death so shortly to be fulfilled, the solemn oath that I had taken, and which Vincey had called on me to answer to in another world than this. Had the man committed suicide? It looked like it. And what was the quest of which he spoke? The circumstances were uncanny, so much so that, though I am by no means nervous, or apt to be alarmed at anything that may seem to cross the bounds of the natural, I grew afraid, and began to wish I had nothing to do with them. How much more do I wish it now, over twenty years afterwards!

As I sat and thought, there came a knock at the door, and a letter, in a big blue envelope, was brought in to me. I saw at a glance that it was a lawyer’s letter, and an instinct told me that it was connected with my trust. The letter, which I still have, runs thus: –

“Sir, – Our client, the late M. L. Vincey, Esq., who died on the 9th instant in – College, Cambridge, has left behind him a Will, of which you will please find copy enclosed and of which we are the executors. Under this Will you will perceive that you take a life-interest in about half of the late Mr. Vincey’s property, now invested in Consols, subject to your acceptance of the guardianship of his only son, Leo Vincey, at present an infant, aged five. Had we not ourselves drawn up the document in question in obedience to Mr. Vincey’s clear and precise instructions, both personal and written, and had he not then assured us that he had very good reasons for what he was doing, we are bound to tell you that its provisions seem to us of so unusual a nature, that we should have bound to call the attention of the Court of Chancery to them, in order that such steps might be taken as seemed desirable to it, either by contesting the capacity of the testator or otherwise, to safeguard the interests of the infant. As it is, knowing that the testator was a gentleman of the highest intelligence and acumen, and that he has absolutely no relations living to whom he could have confided the guardianship of the child, we do not feel justified in taking this course.

“Awaiting such instructions as you please to send us as regards the delivery of the infant and the payment of the proportion of the dividends due to you,

“We remain, Sir, faithfully yours,

“Geoffrey and Jordan.“Horace L. Holly, Esq.”I put down the letter, and ran my eye through the Will, which appeared, from its utter unintelligibility, to have been drawn on the strictest legal principles. So far as I could discover, however, it exactly bore out what my friend Vincey had told me on the night of his death. So it was true after all. I must take the boy. Suddenly I remembered the letter which Vincey had left with the chest. I fetched and opened it. It only contained such directions as he had already given to me as to opening the chest on Leo’s twenty-fifth birthday, and laid down the outlines of the boy’s education, which was to include Greek, the higher Mathematics, and Arabic. At the end there was a postscript to the effect that if the boy died under the age of twenty-five, which, however, he did not believe would be the case, I was to open the chest, and act on the information I obtained if I saw fit. If I did not see fit, I was to destroy all the contents. On no account was I to pass them on to a stranger.

As this letter added nothing material to my knowledge, and certainly raised no further objection in my mind to entering on the task I had promised my dead friend to undertake, there was only one course open to me – namely, to write to Messrs. Geoffrey and Jordan, and express my acceptance of the trust, stating that I should be willing to commence my guardianship of Leo in ten days’ time. This done I went to the authorities of my college, and, having told them as much of the story as I considered desirable, which was not very much, after considerable difficulty succeeded in persuading them to stretch a point, and, in the event of my having obtained a fellowship, which I was pretty certain I had done, allow me to have the child to live with me. Their consent, however, was only granted on the condition that I vacated my rooms in college and took lodgings. This I did, and with some difficulty succeeded in obtaining very good apartments quite close to the college gates. The next thing was to find a nurse. And on this point I came to a determination. I would have no woman to lord it over me about the child, and steal his affections from me. The boy was old enough to do without female assistance, so I set to work to hunt up a suitable male attendant. With some difficulty I succeeded in hiring a most respectable round-faced young man, who had been a helper in a hunting-stable, but who said that he was one of a family of seventeen and well-accustomed to the ways of children, and professed himself quite willing to undertake the charge of Master Leo when he arrived. Then, having taken the iron box to town, and with my own hands deposited it at my banker’s, I bought some books upon the health and management of children and read them, first to myself, and then aloud to Job – that was the young man’s name – and waited.

At length the child arrived in the charge of an elderly person, who wept bitterly at parting with him, and a beautiful boy he was. Indeed, I do not think that I ever saw such a perfect child before or since. His eyes were grey, his forehead was broad, and his face, even at that early age, clean cut as a cameo, without being pinched or thin. But perhaps his most attractive point was his hair, which was pure gold in colour and tightly curled over his shapely head. He cried a little when his nurse finally tore herself away and left him with us. Never shall I forget the scene. There he stood, with the sunlight from the window playing upon his golden curls, his fist screwed over one eye, whilst he took us in with the other. I was seated in a chair, and stretched out my hand to him to induce him to come to me, while Job, in the corner, was making a sort of clucking noise, which, arguing from his previous experience, or from the analogy of the hen, he judged would have a soothing effect, and inspire confidence in the youthful mind, and running a wooden horse of peculiar hideousness backwards and forwards in a way that was little short of inane. This went on for some minutes, and then all of a sudden the lad stretched out both his little arms and ran to me.

“I like you,” he said: “you is ugly, but you is good.”

Ten minutes afterwards he was eating large slices of bread and butter, with every sign of satisfaction; Job wanted to put jam on to them, but I sternly reminded him of the excellent works that we had read, and forbade it.

In a very little while (for, as I expected, I got my fellowship) the boy became the favourite of the whole College – where, all orders and regulations to the contrary notwithstanding, he was continually in and out – a sort of chartered libertine, in whose favour all rules were relaxed. The offerings made at his shrine were simply without number, and I had serious difference of opinion with one old resident Fellow, now long dead, who was usually supposed to be the crustiest man in the University, and to abhor the sight of a child. And yet I discovered, when a frequently recurring fit of sickness had forced Job to keep a strict look-out, that this unprincipled old man was in the habit of enticing the boy to his rooms and there feeding him upon unlimited quantities of brandy-balls, and making him promise to say nothing about it. Job told him that he ought to be ashamed of himself, “at his age, too, when he might have been a grandfather if he had done what was right,” by which Job understood had got married, and thence arose the row.

But I have no space to dwell upon those delightful years, around which memory still fondly hovers. One by one they went by, and as they passed we two grew dearer and yet more dear to each other. Few sons have been loved as I love Leo, and few fathers know the deep and continuous affection that Leo bears to me.

The child grew into the boy, and the boy into the young man, while one by one the remorseless years flew by, and as he grew and increased so did his beauty and the beauty of his mind grow with him. When he was about fifteen they used to call him Beauty about the College, and me they nicknamed the Beast. Beauty and the Beast was what they called us when we went out walking together, as we used to do every day. Once Leo attacked a great strapping butcher’s man, twice his size, because he sang it out after us, and thrashed him, too – thrashed him fairly. I walked on and pretended not to see, till the combat got too exciting, when I turned round and cheered him on to victory. It was the chaff of the College at the time, but I could not help it. Then when he was a little older the undergraduates found fresh names for us. They called me Charon, and Leo the Greek god! I will pass over my own appellation with the humble remark that I was never handsome, and did not grow more so as I grew older. As for his, there was no doubt about its fitness. Leo at twenty-one might have stood for a statue of the youthful Apollo. I never saw anybody to touch him in looks, or anybody so absolutely unconscious of them. As for his mind, he was brilliant and keen-witted, but not a scholar. He had not the dulness necessary for that result. We followed out his father’s instructions as regards his education strictly enough, and on the whole the results, especially in the matters of Greek and Arabic, were satisfactory. I learnt the latter language in order to help to teach it to him, but after five years of it he knew it as well as I did – almost as well as the professor who instructed us both. I always was a great sportsman – it is my one passion – and every autumn we went away somewhere shooting or fishing, sometimes to Scotland, sometimes to Norway, once even to Russia. I am a good shot, but even in this he learnt to excel me.

When Leo was eighteen I moved back into my rooms, and entered him at my own College, and at twenty-one he took his degree – a respectable degree, but not a very high one. Then it was that I, for the first time, told him something of his own story, and of the mystery that loomed ahead. Of course he was very curious about it, and of course I explained to him that his curiosity could not be gratified at present. After that, to pass the time away, I suggested that he should get himself called to the Bar; and this he did, reading at Cambridge, and only going up to London to eat his dinners.

I had only one trouble about him, and that was that every young woman who came across him, or, if not every one, nearly so, would insist on falling in love with him. Hence arose difficulties which I need not enter into here, though they were troublesome enough at the time. On the whole, he behaved fairly well; I cannot say more than that.

And so the time went by till at last he reached his twenty-fifth birthday, at which date this strange and, in some ways, awful history really begins.

III

The Sherd of Amenartas

On the day preceding Leo’s twenty-fifth birthday we both journeyed to London, and extracted the mysterious chest from the bank where I had deposited it twenty years before. It was, I remember, brought up by the same clerk who had taken it down. He perfectly remembered having hidden it away. Had he not done so, he said, he should have had difficulty in finding it, it was so covered up with cobwebs.

In the evening we returned with our precious burden to Cambridge, and I think that we might both of us have given away all the sleep we got that night and not have been much the poorer. At daybreak Leo arrived in my room in a dressing-gown, and suggested that we should at once proceed to business. I scouted the idea as showing an unworthy curiosity. The chest had waited twenty years, I said, so it could very well continue to wait until after breakfast. Accordingly at nine – an unusually sharp nine – we breakfasted; and so occupied was I with my own thoughts that I regret to state that I put a piece of bacon into Leo’s tea in mistake for a lump of sugar. Job, too, to whom the contagion of excitement had, of course, spread, managed to break the handle off my Sèvres china tea-cup, the identical one I believe that Marat had been drinking from just before he was stabbed in his bath.

At last, however, breakfast was cleared away, and Job, at my request, fetched the chest, and placed it upon the table in a somewhat gingerly fashion, as though he mistrusted it. Then he prepared to leave the room.

“Stop a moment, Job,” I said. “If Mr. Leo has no objection, I should prefer to have an independent witness to this business, who can be relied upon to hold his tongue unless he is asked to speak.”

“Certainly, Uncle Horace,” answered Leo; for I had brought him up to call me uncle – though he varied the appellation somewhat disrespectfully by calling me “old fellow,” or even “my avuncular relative.”

Job touched his head, not having a hat on.

“Lock the door, Job,” I said, “and bring me my despatch-box.”

He obeyed, and from the box I took the keys that poor Vinc-ey, Leo’s father, had given me on the night of his death. There were three of them; the largest a comparatively modern key, the second an exceedingly ancient one, and the third entirely unlike anything of the sort that we had ever seen before, being fashioned apparently from a strip of solid silver, with a bar placed across to serve as a handle, and leaving some nicks cut in the edge of the bar. It was more like a model of an antediluvian railway key than anything else.

“Now are you both ready?” I said, as people do when they are going to fire a mine. There was no answer, so I took the big key, rubbed some salad oil into the wards, and after one or two bad shots, for my hands were shaking, managed to fit it, and shoot the lock. Leo bent over and caught the massive lid in both his hands, and with an effort, for the hinges had rusted, forced it back. Its removal revealed another case covered with dust. This we extracted from the iron chest without any difficulty, and removed the accumulated filth of years from it with a clothes-brush.

It was, or appeared to be, of ebony, or some such close-grained black wood, and was bound in every direction with flat bands of iron. Its antiquity must have been extreme, for the dense heavy wood was in parts actually commencing to crumble from age.

“Now for it,” I said, inserting the second key.

Job and Leo bent forward in breathless silence. The key turned, and I flung back the lid, and uttered an exclamation, and no wonder, for inside the ebony case was a magnificent silver casket, about twelve inches square by eight high. It appeared to be of Egyptian workmanship, and the four legs were formed of Sphinxes, and the dome-shaped cover was also surmounted by a Sphinx. The casket was of course much tarnished and dinted with age, but otherwise in fairly sound condition.

I drew it out and set it on the table, and then, in the midst of the most perfect silence, I inserted the strange-looking silver key, and pressed this way and that until at last the lock yielded, and the casket stood before us. It was filled to the brim with some brown shredded material, more like vegetable fi-bre than paper, the nature of which I have never been able to discover. This I carefully removed to the depth of some three inches, when I came to a letter enclosed in an ordinary modern-looking envelope, and addressed in the handwriting of my dead friend Vincey.

“To my son Leo, should he live to open this casket.”

I handed the letter to Leo, who glanced at the envelope, and then put it down upon the table, making a motion to me to go on emptying the casket.

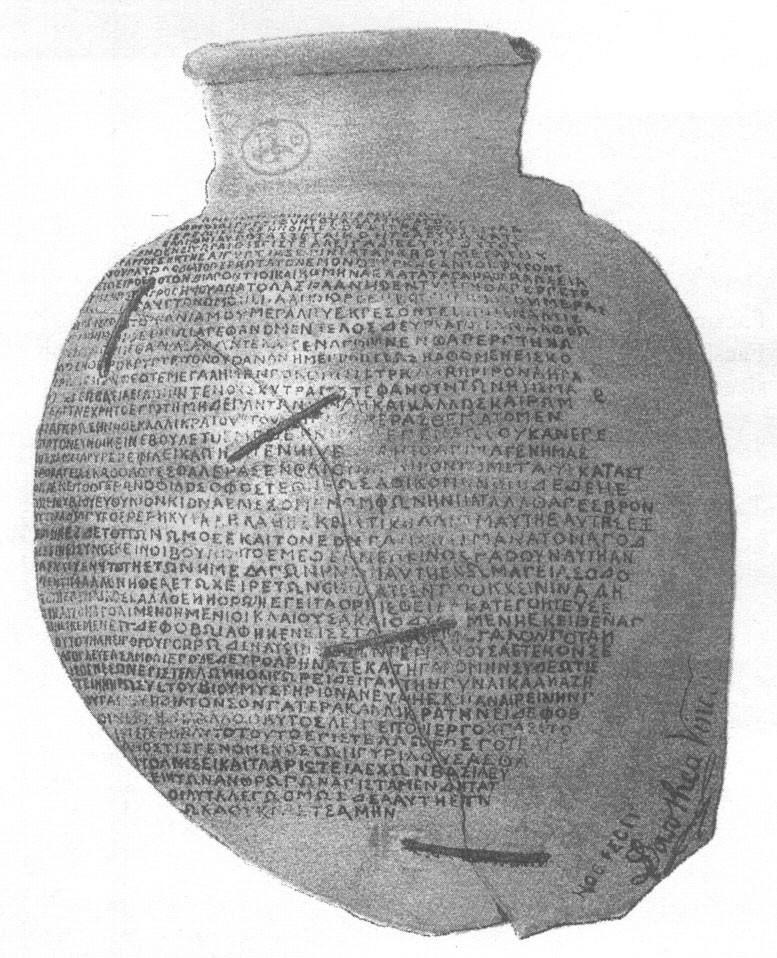

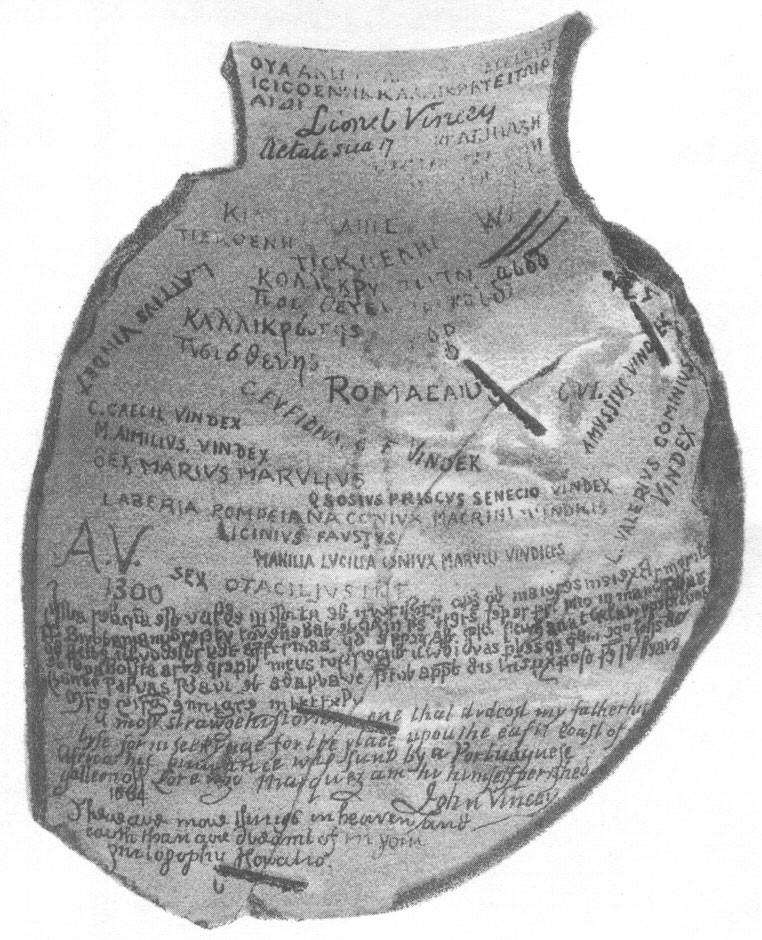

The next thing that I found was a parchment carefully rolled up. I unrolled it, and seeing that it was also in Vincey’s handwriting, and headed, “Translation of the Uncial Greek Writing on the Potsherd,” put it down by the letter. Then followed another ancient roll of parchment, that had become yellow and crinkled with the passage of years. This I also unrolled. It was likewise a translation of the same Greek original, but into black-letter Latin, which at the first glance from the style and character appeared to me to date from somewhere about the beginning of the sixteenth century. Immediately beneath this roll was something hard and heavy, wrapped up in yellow linen, and reposing upon another layer of the fibrous material. Slowly and carefully we unrolled the linen, exposing to view a very large but undoubtedly ancient potsherd of a dirty yellow colour! This potsherd had in my judgment, once been a part of an ordinary amphora of medium size. For the rest, it measured ten and a half inches in length by seven in width, was about a quarter of an inch thick, and densely covered on the convex side that lay towards the bottom of the box with writing in the later uncial Greek character, faded here and there, but for the most part perfectly legible, the inscription having evidently been executed with the greatest care, and by means of a reed pen, such as the ancients often used. I must not forget to mention that in some remote age this wonderful fragment had been broken in two, and rejoined by means of cement and eight long rivets. Also there were numerous inscriptions on the inner side, but these were of the most erratic character, and had clearly been made by different hands and in many different ages, and of them, together with the writings on the parchments, I shall have to speak presently.

[plate 1]

FACSIMILE OF THE SHERD OF AMENARTAS

One 1/2 size

Greatest length of the original 10 1/2 inches

Greatest breadth 7 inches

Weight 1lb 5 1/2 oz

[plate 2]

FACSIMILE OF THE SHERD OF AMENARTAS

One 1/2 size

“Is there anything more?” asked Leo, in a kind of excited whisper.

I groped about, and produced something hard, done up in a little linen bag. Out of the bag we took first a very beautiful miniature done upon ivory, and secondly, a small chocolate-coloured composition scarabaeus, marked thus: –

symbols which, we have since ascertained, mean “Suten se Ra,” which is being translated the “Royal Son of Ra or the Sun.” The miniature was a picture of Leo’s Greek mother – a lovely, dark-eyed creature. On the back of it was written, in poor Vincey’s handwriting, “My beloved wife.”

“That is all,” I said.

“Very well,” answered Leo, putting down the miniature, at which he had been gazing affectionately; “and now let us read the letter,” and without further ado he broke the seal, and read aloud as follows: – “My Son Leo, – When you open this, if you ever live to do so, you will have attained to manhood, and I shall have been long enough dead to be absolutely forgotten by nearly all who knew me. Yet in reading it remember that I have been, and for anything you know may still be, and that in it, through this link of pen and paper, I stretch out my hand to you across the gulf of death, and my voice speaks to you from the silence of the grave. Though I am dead, and no memory of me remains in your mind, yet am I with you in this hour that you read. Since your birth to this day I have scarcely seen your face. Forgive me this. Your life supplanted the life of one whom I loved better than women are often loved, and the bitterness of it endureth yet. Had I lived I should in time have conquered this foolish feeling, but I am not destined to live. My sufferings, physical and mental, are more than I can bear, and when such small arrangements as I have to make for your future well-being are completed it is my intention to put a period to them. May God forgive me if I do wrong. At the best I could not live more than another year.”