Полная версия

India

Another salient of black and red ware suggests a south-east movement from Mathura along the edge of the Vindhya hills. These form the southern perimeter of the Gangetic basin whence, in Bihar, the BRW descends again into the plain. It there re-meets the painted grey ware, a parallel arm of which is discernible extending east along the skirts of the Himalayas. The impression gained is therefore that of a pincer movement, possibly dictated by the problems of clearing the dense forest and draining the swamps which blocked progress along the banks of the Ganga itself. Instead the tide of migration and acculturation seems to have worked its way round the edges, and especially round the top edge. Thus the principal chain of janapada, or clan territories (literally ‘clan-feet’), lay well to the north of the main river, on the banks of the Ganga’s tributaries as they flow down from what is now Nepal. In the Satapatha Brahmana there is even a detailed description of Agni burning a trail eastwards and eventually leapfrogging what is thought to have been the Gandak river so as to ignite the forest beyond and clear its land for settlement and tillage by the Videha clan.

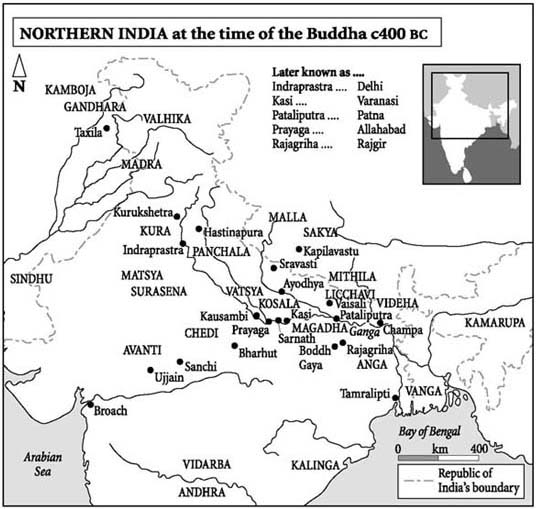

This northerly route of east – west transit and trade, extending from the Panjab and the upper Indus to Bihar and the lower Ganga, now became as much the main axis of Aryanisation as it would subsequently of Buddhist proselytisation and even Magadhan imperialism. It was known as the Uttarapatha, the Northern Route, as distinct from the Daksinapatha (whence the term ‘Deccan’) or Southern Route. The latter, largely the Yadava trail from the Gangetic settlements to Avanti (Malwa) and Gujarat, would also become a much-travelled link giving access to the ports of the west coast and the riches of the as yet un-Aryanised and historically inarticulate peninsula. But it was along the Uttarapatha that the Aryanised territories would first begin to assume the trappings of statehood. Initially those at the western end in the Panjab and the Doab tended to look down on those on the eastern frontier in Bihar and Bengal; the latter were mleccha, uncouth in their arya speech and negligent in their sacrificial observance. By mid-first millennium BC it would be the other way round. As the eastern settlements grew into a network of thriving proto-states, many laid claim to exalted pedigrees and, assuming the mantle of Aryanised orthodoxy, would be happy to disparage their Panjabi cousins as vratya or ‘degenerate’.

THE MAHABHARATA VERSUS THE RAMAYANA

The Ramayana, second of the great Sanskrit epics, has been subjected to the same sort of revision processes as the Mahabharata. So much so that attempting to tease India’s past from such doubtful material has been likened to trying to reconstruct the history of ancient Greece from the fables of Aesop, or that of the Baghdad caliphate from The Thousand and One Nights. The Ramayana’s story is, however, simpler than the Mahabharata’s and its purpose is clearer. No one under Lord Rama’s sway would swap a king for ten harlots, let alone for a thousand slaughterhouses. For in the form we now know it, the Ramayana may be seen as ‘an epic legitimising the monarchical state’.8

When it took this form is uncertain. A condensed version of the story is told in the Mahabharata, but it would appear to be an interpolation. It is certainly no proof that the characters in the Ramayana preceded those in the Mahabharata. The opposite seems more probable, in that Lord Rama’s capital of Ayodhya lay astride the Uttarapatha and five hundred kilometres east of the Kuru/Pandavas’ Hastinapura. That, in its final form, the Ramayana is definitely later than the Mahabharata is shown by the prominence given to regions which are unheard of in the latter. Indeed, while the main wanderings of the exiled Pandavas seem to have been restricted to the immediate neighbourhood of the Doab, those of Lord Rama and his associates are made to extend deep into central and southern India. No doubt much of this was a gloss by later redactors, but it is still precious evidence of the continuing spread of Aryanisation during the first millennium BC. If the Mahabharata hints at the pattern of settlement in the north and west, the Ramayana continues the story eastwards.

Thus while the Mahabharata belongs to the Ganga-Jamuna Doab, the Ramayana is firmly rooted in the middle Ganga region. Rama’s Ayodhya was the capital of an important janapada called Koshala, roughly north-eastern Uttar Pradesh, which some time in mid-millennium would absorb its southern neighbour. The latter was Kashi, which is the old name for Varanasi (Benares). In a popular Buddhist version of the epic, Varanasi rather than Ayodhya actually becomes the locus of the story. And much later, in Lord Shiva’s city, in a quiet whitewashed house overlooking the Ganga and well away from the crowds thronging Dashashwamedh Ghat, the seventeenth-century poet Tulsi Das would pen for the delight of future generations the definitive Hindi version of the epic. Varanasi would make the Ramayana its own, and to this day slightly further upstream, on rolling parkland beside the ex-Maharaja of Varanasi’s palace, the annual week-long performance of the Ram Lila (a dramatised version of the epic) remains one of the greatest spectacles in India.

This suggests that whereas the Mahabharata survives in the popular imagination as a hoard of cherished but disjointed segments, like the scattered skeleton of a fossilised dinosaur, the Ramayana is still alive – indeed kicking, if one may judge by the events of the early 1990s. Casting about for an evocative issue around which to rally Hindu opinion, it was to the sanctity of Ayodhya and its supposed defilement by the presence of a mosque that fundamentalist Hindu opinion turned. Loudly invoking Lord Rama, in 1992 saffron-clad activists duly assailed the Ayodhya mosque and so plunged the proud secularism of post-Independence India into its deepest crisis of conscience.

That Ayodhya/Varanasi score higher in the sacral stakes than Hastinapura/Indraprastra may also have something to do with the different cosmic perspectives of the two epics. A clue is provided by the language of the Puranas, whose genealogies undergo an unexpected change of tense when they reach the Bharata war. From one of Sanskrit’s innumerable past tenses the verb suddenly switches to the future; in effect, subsequent generations as recorded in these genealogies are being prophesied. Given that the lists were not written down until centuries later, the succession of future descendants may be just as authentic as that of past antecedents, indeed rather more so since later names extend into historic times and can be verified from other sources. But the point that the authors of these lists were trying to register was that the great war marked a watershed in time. It was literally the end of an era. The Dvapara Yug, the ‘Third Age’ of Hindu cosmology, came to a close as Pandavas slew Kauravas in the great Bharata holocaust at Kurukshetra, ‘the field of the Kuru’; thereafter the dreaded Kali Yug, the still current ‘Black Age’, began.

Although the battle does not mark the end of the epic, the impression gained is that the Mahabharata is essentially retrospective. It celebrates a vanishing past and may be read as the swansong of an old order in which the primacy of clan kinship, and the martial ethic associated with it, is being slowly laid to rest. In the eighteen-day battle nearly all the Kauravas, plus a whole generation of Pandavas, are wiped out. Yudhisthira, ostensibly the principal victor, surveys the carnage and is overcome with remorse; the rivalry and conflicts endemic in the clan system are repudiated; with the intention of returning to the forest, Yudhisthira asks his followers to accept his abdication. Krishna will have none of it: the ruler must rule just as the warrior must fight; release depends on following one’s dharma, not indulging one’s grief. Reluctantly Yudhisthira concurs, performing the royal sacrifices of rajasuya and aswamedha. But regrets continue, and when Krishna himself dies, it is as if the last remaining pillar of the old order has been removed. All five Pandavas, plus their shared wife Draupadi, can then gratefully withdraw from public life to wander off into the Himalayas.

By way of contrast, the Ramayana may be considered as decidedly forward-looking. It opens new frontiers and it formulates a new ideal. Although nothing is said about a new era or a system of governance specifically designed for it, the implication is clear. When Rama eventually regains his capital, it is not to indulge in remorse or even to reaffirm Vedic values but to usher in a dazzling utopia of order, justice and prosperity under his personal rule. The resultant Rama-rajya (or Ram-raj in Hindi, ‘the rule of Rama’) quickly became, and is still, the Indian political ideal, invoked by countless dynasts and pledged by countless politicians, secularist as well as Hindu nationalist. Likewise Ayodhya itself would come to represent the model of a royal capital and as such would feature in many subsequent Aryanised state systems. In this guise it would travel far, making landfalls in Thailand where Ayuthia, the pre-Bangkok capital of the Thai monarchs, supposedly replicated Rama’s city, and even in central Java where the most senior sultanate is still that of Jogjakarta, or Ngajodya-karta, the first part of which is a Javanese rendering of ‘Ayodhya’.

MONARCHIES AND REPUBLICS

Legitimising monarchical rule, in India as in south-east Asia, was the Ramayana’s prime function. But in both places its use for this purpose was dictated as much by current challenges as by residual loyalties to a past order. For in north India of the mid-first millennium BC other experiments in the organising of a state were already well underway. Monarchical authority was not, it seems, essential to state-formation. Nor was its absolutism, as heavily promoted by its brahman supporters, congenial to all. Other sources suggest dissent and bear copious testimony to alternative state systems with very different constitutions.

The textual sources concerned are all either Buddhist or Jain. Nataputta, otherwise Mahavira (‘Great Hero’), would formulate the Jain code of conduct in the sixth-to-fifth centuries BC, just when Siddhartha Gautama, otherwise the Buddha (‘Enlightened One’), was preaching the Middle Way. This was a coincidence of profound moment. It would make the history of the mid-Gangetic plain in the first millennium BC a subject of abiding and even international interest; more immediately, it directs the historian’s attention to aspects of contemporary Indian society that would otherwise be ignored. For the lives and teachings of the great founding fathers of Buddhism and Jainism quickly inspired a host of didactic and narrative compositions which supplement and sometimes contradict orthodox sources like the Puranas. Moreover, both men were born into distinguished clans which belonged not to kingdoms modelled on Rama’s Ayodhya but to one of these alternative, non-monarchical state systems. Jain and Buddhist versions of the Ramayana story, or of episodes within it, thus show a rather different emphasis. They also incorporate significant information on places other than Ayodhya and on state systems other than monarchies.

These alternative state systems have been variously interpreted as oligarchical, republican or even democratic. The term now used for them is gana-sangha, evidently a compromise reached after some early-twentieth-century scholarly sniping, since we are told that ‘in the years 1914–16 a great controversy raged [presumably amongst blissfully bunkered academics] about the term gana.’9 A variant of jana, basically it means a ‘clan’ or ‘horde’ which, qualified by sangha, an ‘organisation’ or ‘government’, supposedly gives a meaning of ‘government by discussion’. Such ‘governments by discussion’, or more commonly ‘republics’, could of course take many forms. The extent to which all or only some of their constituents participated in decision-making, the institutions and assemblies through which they did so, and the degree to which they elected or merely endorsed a leadership are not clear. Nevertheless, all these matters are currently the subject of debate, partly because of obvious parallels with the contemporary republics and democracies of ancient Greece, and partly because modern India itself has a republican and democratic constitution whose pedigree occasionally generates some warmth.

That a clan-based society should opt for a constitution which was more egalitarian and less autocratic than monarchy seems perfectly logical. In a sense the republics merely institutionalised traditions of consultation amongst the leading clansmen which go back to Vedic times. These took the form of assemblages which ranged from the open samiti to the more restricted and specialised sabha and parisad. As consultative groups the latter would develop into ministerial councils in the monarchical states, while the former seems to have retained its sovereign status in the republics.

Most of the mid-millennium republics of Bihar and Uttar Pradesh (UP) – those of the Licchavis, Sakyas, Koliyas, Videhas, etc. – came into being as a result of the usual process of segmenting off from a parent clan. In due course the breakaways claimed their own janapada, their territory, and perhaps intentionally, perhaps through neglect or penury, they skimped on performing the full programme of Vedic sacrifices and paid scant attention to brahmanical authority. Surplus produce and booty, when they materialised, would not therefore have necessarily been ‘burned off’ in ritual orgies designed to impress the gods and enhance the sacrificer’s prestige. Instead they would have become available for other purposes, like administration, urbanisation, industry and trade.

This, however, is a simplistic explanation for the emergence of states, and would certainly not have encouraged the formation of monarchies. In brahmanic tradition kingship is said to have been pioneered by the gods. Facing defeat by their supernatural enemies, the gods put their heads together and decided to choose a leader; Indra got the job. A raja, in other words, should be chosen by his peers, his role was principally military, and his raj had the sanction of divine precedent. Other myths reformulated the concept. One, already noticed, promoted kingship as the only insurance against anarchy. In the evil times ushered in by the Kali Yug, men found themselves obliged to compete with one another for wealth, women and favour. Society was thus reduced to the free-for-all of matsya-nyaya (‘the law of the fishes’, i.e. of the jungle); and men were accordingly obliged to formulate rules of conduct and to seek a means of enforcing them. The gods, or Lord Vishnu in the shape of that rapidly growing fish, proposed a raja; and they selected Manu. He agreed, but only on four nicely judged conditions – that he receive a tenth of his subjects’ harvest, one in every fifty of their cows, a quarter of all the merit they earned, and the pick of their choicest maidens. In other words, authority and law-enforcement were the now raja’s main responsibilities; he was chosen by the gods rather than men; and under an advantageous reciprocal arrangement he had a right to a substantial contribution of the good things his subjects produced.

Here, then, was a firm ideological basis for kingship. But while the element of contract implicit in the Manu myth was much emphasised by Buddhist sources, brahmanic sources focused on the element of divine sanction. Either way, a monarch was theoretically subject to constraints, human or divine, and should not be regarded as an outright despot. Conversely, all theories of kingship provided ample justification for the administrative and coercive structures which would constitute a state system.

But as with the more spontaneous evolution of the gana-sanghas (republics), state-formation was prompted not simply by the appeal or logic of a particular constitution. Just as important were the challenges and opportunities created by new technologies and new social and economic conditions. It seems fairly certain from the abundance of artefacts unearthed by archaeology that, by mid-millennium, population densities had increased, and that migration had slowed as the more easily worked tracts became settled. The population increase owed as much to the incorporation, or Aryanisation, of indigenous peoples as to a soaring birth-rate amongst the immigrants; and both processes would heighten social awareness and caste/class distinctions.

On the other hand, agricultural production seems to have more than kept pace with the growing population. The use of heavy ploughs drawn by eight oxen or more, the widespread adoption of rice and the development of irrigation are all well attested by 500 BC: ‘Buddhist texts describe rice and its varieties with as much detail as the Rig Vedic hymns refer to cows.’10 It has been suggested that the wetter soils of northern Bihar were so unsuitable for barley that only some understanding of wet rice-cultivation would have made them worth settling. The effort of clearing such lands and building embankments for water retention would still have been arduous; yet it paid off. By the sixth-fifth centuries BC the Lichhavi and other republics north of the Ganga would together represent a formidable power well capable of meeting a challenge from their monarchical neighbours, notably the Koshala/Kashi kingdom in the south-west and, south-east across the Ganga, the aggressive new dynasty of Magadha.

More intensive farming regimes also made for new attitudes towards the land. The grazier’s seasonal parameters had given way to the fixed dimensions of the ploughman’s field. Anchored to a dependable supply of water and labour, the grama grew into a village of mud-brick housing which was home both to families of clan descent and to a growing band of socially differentiated dependants and subordinates. From the village there now spread a quilt of carefully supervised plots within a network of ditchings. The common rights of ownership typical of a pastoral society were being edged out by local initiative and the use of subject labour. Quick to claim the fields which they had reclaimed, the grhpatis, or heads of households, pressed for title to land, labour and water as the best way to meet their obligation of supplying the livestock and, increasingly, the grain needed for the leadership’s ritual sacrifices. Imperceptibly terms like bali, which originally meant an offering intended for the clan-chief’s sacrificial disposal, came to denote a fixed and regular contribution which, when subject to record and assessment, duly became a tax. Similarly bhaga, originally a ‘share’ of the spoils of war exacted by the chief, came to signify a tax on produce, usually of one sixth.

As cultivable land came to be considered as familial property, so the wider but ill-defined janapada, the ancestral territory of a particular clan, assumed fixed boundaries. The Gangetic basin’s abundant rivers and riverbeds made convenient frontiers for the newer janapada in the east. Buddhist texts list sixteen maha-janapada, or major janapada, as having been extant in the sixth century BC. They extended from Gandhara and Kamboja in the north-west of what is now Pakistan to Avanti and Chedi in central India and Anga and Kalinga in Bengal and Orissa. Soon to be known as rashtra, or ‘kingdoms’, many still retained their tribal names; Kuru was still the land of the Kuru, and Malla of the Malla. But allegiance was now dictated less by the horizontal bonds of kinship and more by the vertical ties of economic and social dependency. Instead of being focused on tribe or clan, loyalty was increasingly to the territory itself, to the individual or body which had sovereignty over it, and to the town or city where that power resided.

CITY AND CASTE

India’s second urbanisation (the first being that of the long-forgotten Harappans) may be attributed partly to this process of state-formation and to the institutions it engendered, and partly to the surplus generated by the new agricultural regime pioneered in the east. The post-Vedic texts, of course, would have us believe that towns and cities had dotted the land for aeons. But it is only from C600 BC that archaeology lends any weight to their optimistic imagery. Earthen ramparts of about this period have been uncovered at Ujjain (in Malwa), Varanasi and Kaushambi (the post-Hastinapura capital of the Kuru, west of Allahabad). These ramparts have ‘civic dimensions and must have enclosed real cities’.11 Other sites like that of Sravasti, the post-Ayodhya capital of Koshala, and Rajgir, the Magadha capital, seem soon to have followed suit. In the west, Taxila and Charsadda may have preceded them; but that was under a different impetus if not a different dispensation. In the north-west, with stone plentiful, there is also evidence of monumental structures.

Nothing comparable is found in the city sites of the Gangetic basin; even kiln-fired brickwork, the Harappans’ speciality, does not reappear until the last centuries BC. Buildings, including state edifices and royal residences, were evidently of timber and mud. The first Buddhist stupas (commemorative mounds, often erected over relics of the Buddha) were of just such perishable materials, although it was precisely these sacred structures which would be amongst the earliest to be clad, then gloriously cloistered, in stone. Of architecture and sculpture, the signposts to so much of later Indian history, nothing remains.

Although unused, the technology for kiln-fired bricks was familiar enough, for what distinguishes this period of urbanisation is a new and invasive ceramic ware. Known as the northern black polished (NBP), it first appears after 500 BC, rapidly supersedes the earlier styles (PGW, BRW) in Bihar and UP, and eventually extends west across the Doab and deep into Panjab, east to Bengal and south to Maharashtra. Were there no other evidence for urbanisation, the concentrated finds of this high-quality ware would prompt the idea of city life. Similarly, were there no other evidence than its widespread distribution, one might yet guess that such standardisation amongst the numerous kingdoms and gana-sanghas of north India during the last half of the first millennium BC must presage some major new integrational influence. Sure enough, within two centuries of the NBP ware’s first appearance, all of north India (plus much more besides) would be conspicuously linked by the first and the most extended of India’s home-grown empires.

Trade, of course, also played its part. The first coins are datable to the mid-millennium and are found mostly in an urban context. Of silver or copper, they were punch-marked (rather than minted) with symbols thought to be those of particular professional groups, markets and cities. They ‘were therefore a transitional form between traders’ tokens as units of value and legal tender issued by royalty’.12 The cash economy had evidently arrived, and with references to money-lending, banking and commodity speculation becoming commonplace in Buddhist literature it is clear that venture capital was readily available. Items traded included metals, fine textiles, salt, horses and pottery. Roads linked the major cities, although river transport seems to have been favoured for bulky consignments.

All of which presupposes the existence of specialised professions: artisans and cultivators, carters and boatmen, merchants and financiers. It was all a far cry from the clan communities of the Vedas. North Indian society had been undergoing structural changes every bit as radical as those affecting its agricultural base and its political organisation. These changes are usually interpreted in terms of the emerging caste system. They have to be extracted, with some difficulty, from the changing terms used to designate individuals and social groups in the different texts. And it would appear that the process of change was gradual, uneven and complex.