Полная версия

India

The Nanda family undeniably commanded the most formidable standing army yet seen in India. Military statistics readily lend themselves to exaggeration, especially when provided by a disappointed adversary. Yet the Nandas’ army of 200,000 infantry, twenty thousand cavalry, two thousand four-horse chariots and three to six thousand war-elephants would have represented a formidable force even if decimated by roll-call reality. It was certainly enough to strike alarm in stout Greek hearts, to awaken in them fond memories of Thracian wine and olive-rich homesteads beside the northern Aegean, and to send packing the age’s only other contender as a ‘one umbrella’ world ruler.

THE MACEDONIAN INTRUSION

Alexander the Great’s Indian adventure, though a subject of abiding interest to generations of classically-educated European historians, is not generally an episode on which historians of Indian nationality bother to dwell. They rightly note that it ‘made no impression historically or politically on India’, and that ‘not even a mention of Alexander is to be found in any [of the] older Indian sources.’8 ‘There was nothing to distinguish his raid in Indian history [except “perfidious massacres” and “wanton cruelty”]… and it can hardly be called a great military success as the only military achievements to his credit were the conquest of some petty tribes and states by instalment.’9

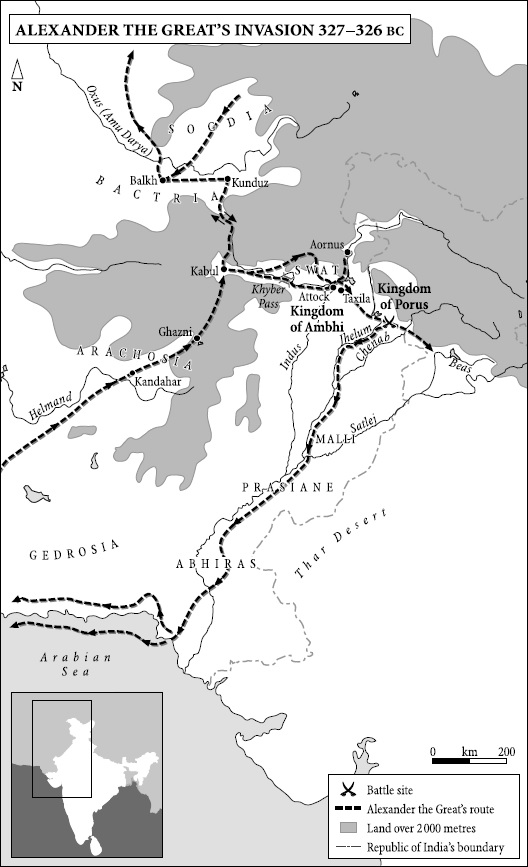

Alexander’s great achievement was not invading India but getting there. A military expedition against the Achaemenid empire, originally planned by his father, became more like a geographical exploration as the men from Macedonia triumphantly probed regions hitherto undreamed of. Anatolia, the modern Turkey, was overrun in 334–3 BC. To protect his southern flank before invading Persia, Alexander then swept down through Phoenicia (Syria and Palestine) to claim Egypt and Libya. That was in 333–2. In 331–0 the last Achaemenid ruler was chased from his homeland and Persepolis was sacked. The twenty-five-year-old Alexander was now master of all that had comprised the largest empire the world had yet seen – all, that is, except for its easternmost provinces, including Gandhara and ‘India’.

Although Indian troops still served in the Achaemenid forces, it seems that Gandhara and ‘India’ had probably slipped from direct Achaemenid rule some time in the mid-fourth century BC. For Alexander it was enough that once upon a time these provinces had indeed been Persian; to excel Darius and Xerxes, he must needs take them. First, though, another long detour was necessary, this time along his northern flank. In 329–8 he pushed north-east into Arachosia (Afghanistan) and then crossed in succession the snows of the Hindu Kush, the swirling Oxus river and the parched scrubland of Sogdia (Uzbekistan). He then laid claim to the Achaemenids’ central Asian frontier on the distant Jaxartes (Syr) beyond Samarkand. It was not till late 327 BC that, returned to the vicinity of Kabul, he was ready with a force of fifty thousand to cross India’s north-west frontier.

Determined now to upstage not only the empires of Darius and Xerxes but also the mythical conquests of Heracles and Dionysos, Alexander seems increasingly to have seen his progress in terms of a Grail-like quest for the supposedly unattainable. He sought the ‘ocean’, the ultimate limit of terrestrial empire. Through knowledge of this great ‘beyond’, he aspired to a kind of enlightenment which, although very different from that of the Buddha, would become a cliché of Western exploration. More crudely, he hankered after sheer bloody immortality. ‘His motives need a little imagination,’ writes the best of his biographers, who then quotes one of Alexander’s companions: ‘The truth was that Alexander was always straining after more.’10

More was precisely what India offered. Like a tidal wave, news of Alexander’s prowess had swept ahead of him, flattening resistance and sucking him forward. Indian defectors from the Achaemenid forces primed his interest and paved the way; local malcontents promised support and provided elephants; judicious potentates sought his friendship. Principal amongst the latter was a king known to the Greeks as ‘Omphis’ or ‘Taxiles’. As the latter name implied, he was the ruler of Taxila, reportedly the largest city between the Indus and the Jhelum; and from a chance mention in an appendix to Panini’s grammar he has since been identified as Ambhi, an otherwise enigmatic figure in Indian tradition.

‘The first recorded instance of an Indian king proving a traitor to his country’11 seems an over-harsh judgement on the ambiguous Ambhi of Taxila. Alexander had divided his forces so that half marched largely unopposed down the Kabul river and across the Khyber Pass, while he himself led the remainder by a northerly route through the wintry hills to Swat. There, up among the pine forests of the supposedly impregnable hill fort of Aornos (Pir-i-Sar), he inflicted one of several vicious and salutary defeats on the mountain tribes. By the spring of 326 BC, when back in the plains he crossed the Indus to join up with the rest of his forces, the Macedonian’s reputation stood high.

A city built on trade and scholarship with little in the way of natural defences stood no chance. Taxila had survived the Achaemenids, indeed was a part-Achaemenid city. It could manage the Greeks in the same way. When Alexander descended to the Indus he found thousands of cattle and sheep, as well as elephants and silver, awaiting him. Ambhi, with nought to gain by resistance except the annihilation of his illustrious city and the applause of a very remote posterity, was playing safe. Alexander confirmed him as his satrap and generously repaid his liberality.

At the time Taxilan territory extended modestly from the Indus to the Jhelum. Beyond, occupying the next sliver of the Panjab between the Jhelum and the Chenab, the kingdom of ‘Porus’ lay across the invaders’ line of march. In Greek as in Indian tradition, Porus is all that Ambhi is not. A giant of a man, proud, fearless and majestic, he may have owed his name to Paurava descent, the Pauravas being only slightly less distinguished than the Bharatas in the pecking order of Vedic clans. Alexander had summoned him, along with other local rulers, to meet him and render tribute. Porus welcomed a meeting, adding casually that an appropriate venue would be the field of battle.

As good as his word, and despite the fact that the monsoon had already broken, Porus massed his forces on the banks of the Jhelum. Normally the monsoon brought all campaigning in India to an end. Indian troops were ill-equipped to fight in the rain, and Porus probably trusted to the flooding Jhelum to halt the enemy. But Alexander, well used to river crossings, organised boats, duped the enemy as to his crossing place, and between torrential downpours gained the further bank. The battle that followed was anything but a formality. Porus’ chariots slithered uncontrollably in the mud and his archers could find no purchase for their massive bows, one end of which had to be planted in the ground. Yet the Indian forces, though outnumbered as more of the enemy crossed the river, fought valiantly. Abristle with spearsmen, the elephant corps trundled across the battlefield like towering bastions on the move. Their repeated charges drove all before them, the Greeks merely peppering them with missiles as they reformed. But Alexander now knew enough of elephants to bide his time. His tactical skills were unmatched, and his cavalry easily outmanoeuvred their rivals. As the battle wore on, the Indians found themselves penned into an ever smaller circumference. Enraged elephants now trampled friend and foe alike. Exhausted, ‘they then fell back like ships backing water, and merely kept trumpeting as they retreated with their face to the enemy’. With shields linked, the Macedonian phalanx then pressed in for the kill. ‘Upon this, all turned to flight wherever a gap could be found in the cordon of Alexander’s cavalry,’ according to the account compiled by Arrian.

Porus, wounded but still conspicuously fighting from the largest of the elephants, was captured. ‘How did he expect to be treated?’ asked Alexander. ‘As befits a king,’ he famously replied. To the Greeks it sounded, under the circumstances, like an extraordinarily noble and fearless request. Alexander responded magnanimously, reinstating him as king and subsequently augmenting his territories. But Porus’ words could as well have been those of Lord Krishna, whose advice to Arjuna in the Mahabharata made much the same point. Each must live according to his dharma; it was the dharma of a ksatriya to fight and to embrace the consequences. Probably Porus was not boldly appealing to Alexander’s clemency, nor presuming on some brotherhood of sovereignty; he was simply stating his dharma.

After exceptionally elaborate celebrations, the Macedonians moved on, continuing east and south across the grain of the Panjab river system. The rains ended and the land blossomed. They crossed the Chenab, then the Ravi. Countless ‘cities’ capitulated, others, some evidently republican gana-sanghas, offered a short-lived resistance. Even to Alexander it was becoming apparent that ‘there was no end to the war as long as an enemy remained to be encountered’. Rumours of the vast forces commanded by the Nandas of Magadha (the ‘Gangaridae’ and ‘Prasii’ to the Greeks) now began to infiltrate the ranks. ‘This information only whetted Alexander’s eagerness to advance further,’ says Arrian. The Ganga, mightier even than the Indus, must surely carry them to the ocean at the end of the world. Its plain was reported as exceedingly fertile, its peoples excellent farmers as well as doughty fighters, and its governments civilised and well organised. Alexander sniffed the prospect of an even more glorious dominion.

But his men were unimpressed. They crossed what is now the frontier between Pakistan and India somewhere in the vicinity of Lahore. Then, near Amritsar, they reached the Beas, fourth of the Panj-ab, the ‘five rivers’. In this weird and interminable land where the clothes were all white and the complexions all black, it was as good a place as any for a showdown with their commander.

Alexander sensed the mood of mutiny. In a lengthy appeal to his commanders he invoked their past loyalty and stressed the consequences of retreat. Extricating themselves would be difficult. Were the tide of conquests now to ebb, they would find the sands sucked from under their feet. New friends would review their allegiance and old enemies would take their chance. Trumpeting an empty defiance, the Greeks would find themselves backing away amidst a shower of missiles just like Porus’ exhausted elephants.

But to men who had been on the march for eight years, such arguments had little appeal. They had bathed in the Tigris and the Indus, the Nile and the Euphrates, the Oxus and the Jaxartes. Across desert, mountain, steppe and field they had trudged for over twenty-five thousand kilometres. Of victory, booty, glory and novelty they had had their fill. With respect and real affection, they listened to their leader, moved but unpersuaded.

Alexander withdrew to his tent like his hero Achilles. A three-day sulk made no greater impression on the men’s resolve, while a sacrifice for safe passage of the river produced only adverse omens. In the end Alexander had no choice but to announce a withdrawal. The banks of the Beas erupted with cheers of relief; many wept but all rejoiced. As Arrian noted, Alexander was vanquished only once – and that by his own men.

To round off his conquests, complete his explorations, and disguise his failure, Alexander opted to return by sailing down the Jhelum and the Indus to the ocean. Ships were readied and he sailed in late 326 BC. The voyage downriver took six months. Stern opposition came from numerous riverine peoples, some of whom have been tentatively identified, and from sizeable townships which clearly included well established brahman communities. Some of these townships no doubt occupied sites beneath which the Harappan cities had already lain, cocooned in alluvial oblivion, for 1500 years.

In an engagement with the ‘Malloi’ Alexander himself was seriously wounded. An arrow struck him in the chest and may have punctured his lung. He barely recovered. The wisdom of forgoing a contest with the Nandas’ multitudinous cohorts was amply demonstrated; so were the dangers of withdrawal. With few regrets, in September 325 BC the fleet sailed out of the Indus into the Arabian Sea. Meanwhile Alexander led the rest of his men west on what proved to be, for many, a death-march to Babylon along the desert coast of Gedrosia (Makran). There was still some talk of returning to India, of resuming the march with fresh troops, and of consummating the ultimate conquest. But other appetites proved Alexander’s undoing. Within two years he died from hepatoma following a massive banquet in Babylon.

With him from India had gone the wherewithal for a vastly enriched Western image of the land beyond the Indus. He had prised open a window on the East through which emissaries would pass, ideas would shine, and prying eyes would covet. With him too went all those Hellenised personae and places – Omphis, Aornos, Porus, the Malloi and countless others – never to be heard of again in India’s history. The ‘invasion’ had amounted to little more than a hasty intrusion, scuffing a corner of the carpet but neither baring its boards nor troubling its political furniture.

With Alexander there had also gone one ‘Calanus’, a figure worth remembering in that he seems to be the first Indian expatriate to whom a name and a date can confidently be given. One of a group of ascetics encamped near Taxila, Calanus had accepted Alexander’s invitation to join him in that city and subsequently accompanied him back to the west. There, in Persia shortly before his patron’s death, his own death would cause a sensation.

Calanus’ doctrinal persuasion is uncertain. As one of his companions at Taxila had put it, trying to explain one’s philosophy through a wall of interpreters was like ‘asking pure water to flow through mud’. In that Calanus and his friends went naked, a condition in which no Greek could be persuaded to join them, they may have been nigrantha or Jains. Jain nudity was dictated by that sect’s meticulous respect for life in all its forms. Clothes were taboo because the wearer might inadvertently crush any insect concealed in them; similarly death had to be so managed that only the dying would actually die. Jains bent on ending their life, therefore, usually starved themselves to death. Yet Calanus, a man of advanced years, chose to immolate himself on his own funeral pyre. Though an extraordinarily stoical sacrifice in Greek eyes, this was a decidedly careless move for one dedicated to avoiding casual insecticide. Evidently the Persian winter had induced a chill, if not pneumonia, and Calanus had decided it was better to die than be an encumbrance. No one, not even Alexander, could dissuade him from his purpose. He strode to his cremation at the head of an enormous procession and reclined upon the pyre with complete indifference. This composure he maintained even as the flames frazzled his flesh.

Visibly shaken by such an exhibition, the Greeks held a festival in his honour and drowned their sorrows in a Bacchanalian debauch. Calanus, though he had made no converts, had won many friends. He also left a profound impression well worthy of India’s first cultural emissary. ‘Gymnosophists’, or ‘naked philosophers’, henceforth became stock figures in the Western image of India. As ‘Pythagoreans’, they were also identified with Greek traditions of abstinence and the conjectures of Pythagoras about rebirth and the transmigration of the soul. Lucian, Cicero and Ambrose of Milan all wrote of Calanus and his naked companions. Much later, as the epitome of ascetic puritanism, India’s gymnosophists would be revered by, of all people, Cromwellian fundamentalists. And later still, as mystics, gurus and maharishis, they would come again to minister to another spiritually impoverished Western clientele.

5 Gloria Maurya C320–200 BC

FLASHES OF INSPIRATION

ALTHOUGH SEVERAL of those who marched east with Alexander wrote of their travels, and although other contemporaries and near-contemporaries compiled lives of Alexander and geographies based on his exploits, none of these survives. Such accounts were, though, still current in Roman times and were used by authors, including Plutarch, the first-century AD biographer, and Arrian, the second-century AD military historian, to compile their own works on Alexander. These do survive. They do not always agree; scraps of information gleaned from other later sources are included indiscriminately; and when describing India, they often dwell on fantastic hearsay. To the gold-digging ants of Herodotus were now added a gallery of gargoyle men with elephant ears in which they wrapped themselves at night, with one foot big enough to serve as an umbrella, or with one eye, with no mouth and so on.

Allowing for less obvious distortions, these accounts yet provide vital clues to the emergence after Alexander’s departure of a new north Indian dynasty, indeed of an illustrious empire, one to which the word ‘classical’ is as readily applied as to those of Greece and Rome – and with good reason, in that it has since served India as an exemplar of political integration and moral regeneration.

In 326 BC, when Alexander was in the Panjab, ‘Aggrames’ or ‘Xandrames’ ruled over the Gangetic region according to these Graeco-Roman accounts. His was the prodigious army at which Alexander’s men had balked; and his father was the low-born son of a barber and a courtesan who had founded a dynasty with its capital at Pataliputra. ‘Andrames’ was therefore a Nanda, probably the youngest of Mahapadma Nanda’s sons. And since, unusually, these Graeco-Roman accounts agree with the Puranas that Nanda rule lasted only two generations, he was the last of his line. Immensely unpopular as well as dismally documented, the second Nanda was about to be overthrown.

According to Plutarch, Alexander had actually met the man who would usurp the Magadhan throne. His name was ‘Sandrokottos’ (‘Sandracottus’ in Latin) and in 326 BC he was in Taxila, perhaps studying and already enjoying Taxilan sanctuary as he prepared to rebel against Nanda authority. No such person, however, is known to Indian tradition, the voluminous king-lists in the Puranas containing no mention of a ‘Sandrokottos’ sound-alike. Although from other Greek sources, especially the account of Megasthenes, an ambassador who would visit India in C300 BC, it was evident that someone called Sandrokottos had indeed reigned in the Gangetic valley, it was still not clear to which if any of the many listed Indian kings he corresponded, nor whether he ruled from Pataliputra, nor whether he could be the same as Plutarch’s Sandrokottos. Like Porus and Omphis, it looked as if Sandrokottos was either a minor figure or else someone whose name had been so hopelessly scrambled in its transliteration into Greek that it would never be recognisable in its Sanskritic original.

It was Sir William Jones, the charismatic father of Oriental studies and pioneer of Indo-Aryan linguistics, who in another flash of inspiration rescued the reputation of Sandrokottos. ‘I cannot help mentioning a discovery which accident threw my way,’1 he told members of the Bengal Asiatic Society in his 1793 annual address. In the course of exploratory forays into Sanskrit literature he had earlier worked out that Sandrokottos’ capital could indeed have been the Magadhan city of Pataliputra. He had now come across a mid-first-millennium AD drama, the Rudra-rakshasa, which told of intrigues at the court of a King Chandragupta who had usurped the Magadhan throne and received foreign ambassadors there. The flash of inspiration, the ‘chance discovery’, was that ‘Sandrokottos’ might be a Greek rendering of ‘Chandragupta’. This was later established by the discovery of an alternative Greek spelling of the name as ‘Sandrakoptos’. The ‘Sandrokottos’ of Plutarch and of Megasthenes, and the Chandragupta of this play and of occasional mention in the Puranas, must be the same person. Crucially and for the first time, a figure well known from Graeco-Roman sources had been identified with one well-attested in Indian tradition.

At the time, the late eighteenth century, the excitement generated by this discovery stemmed from its relevance for Indian chronology. Very little was yet known of Chandragupta or the empire he had founded; the latter would only be recognised as an exceptional creation following even more exciting discoveries in the nineteenth century. In Jones’s day his breakthrough was applauded solely because it at last made possible some cross-dating between, on the one hand, kings (with their regnal years) as recorded in the Puranas and, on the other, ascertainable dates in the history of western Asia. Thus, for instance, if Chandragupta was planning his rebellion against the Nandas when Alexander was in the Panjab, if according to Indian tradition he ruled for twenty-four years, and if Megasthenes, the Greek ambassador to the court of ‘Sandrokottos’, could not have been sent until after 305 BC, it followed that Chandragupta’s revolt must have started soon after 326 BC and have lasted three to four years, so that he then reigned from his many-pillared palace in Pataliputra from approximately 320 to 297 BC. That meant that his successor, Bindusara, ruled from 297 to 272 BC, and that Bindusara’s successor, an enigmatic figure who had yet to be clearly identified (let alone accorded universal recognition as ‘one of the greatest monarchs the world has ever seen’2), must have acceded (after a four-year interregnum) in about 268 BC.

These dates have since been further substantiated by cross-reference with later Buddhist sources. Buddhist and Jain texts have much to say about the dynasty they call ‘Maurya’ and, along with surviving extracts of the report written by ambassador Megasthenes, plus a truly remarkable series of inscriptions, they constitute important sources for the period. But what would make the early Mauryan empire potentially the best-documented period in the entire history of pre-Muslim India was the discovery of that classic of Indian statecraft, the immensely detailed if almost unreadable text known as the Arthasastra. For it would appear that Kautilya, the steely brahman to whom the work is credited, was none other than the instigator, operative, ideologist and chief minister of the self-same Chandragupta. In fact orthodox tradition has it that Kautilya was the kingmaker, and Chandragupta little more than his adopted protégé. Kautilya’s great compendium, therefore – with its exhaustive listing of the qualifications and responsibilities required of innumerable state officials, its schema for the conduct of foreign relations and warfare, its enumeration of the fiscal and military resources available to the state, its ruthless suggestions for law enforcement and the detection of dissent, its advocacy of state intervention in all aspects of social and economic activity, and its rules-of-thumb for just about every conceivable political eventuality – such a work should indeed supply uniquely well informed and authoritative insights into the workings of the Mauryan state.

There are, though, grounds for caution. The full text of the Arthasastra is comparable in size and excruciating detail to the Kamasutra but, though cited ‘sometimes eulogistically and sometimes derisively’3 in other ancient works, it was only discovered in 1904. For Dr R. Shamasastry, the then government of Mysore’s chief librarian, as for Sir William Jones, the discovery was accidental. An anonymous pandit simply handed over the priceless collection of palm leaves on which it was written, and then disappeared. Happily, Shamasastry quickly divined the importance of his acquisition; he was also well qualified to undertake its organisation and elucidation. His English translation was published in 1909, since when other editions have appeared and controversy may be said to have raged.