Полная версия

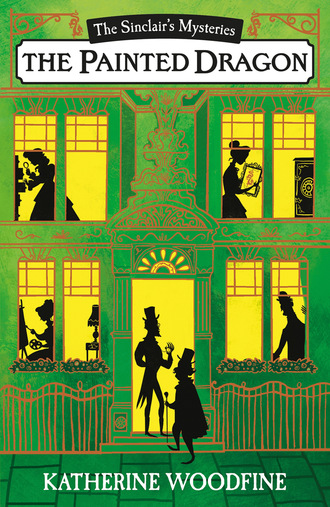

The Painted Dragon

First published in Great Britain 2017

by Egmont UK Limited

The Yellow Building, 1 Nicholas Road, London W11 4AN

Copyright © Katherine Woodfine, 2017

Illustrations copyright © Karl James Mountford, 2017

First e-book edition 2017

ISBN 978 1 4052 8289 5

Ebook ISBN 978 1 7803 1748 9

www.egmont.co.uk

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Stay safe online. Any website addresses listed in this book are correct at the time of going to print. However, Egmont is not responsible for content hosted by third parties. Please be aware that online content can be subject to change and websites can contain content that is unsuitable for children. We advise that all children are supervised when using the internet.

For Jackie and Zoe, for all the mysteries and adventures

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

PART I: White Dragon

CHAPTER ONE

CHAPTER TWO

CHAPTER THREE

CHAPTER FOUR

CHAPTER FIVE

CHAPTER SIX

PART II: Green Dragon

CHAPTER SEVEN

CHAPTER EIGHT

CHAPTER NINE

PART III: Red Dragon

CHAPTER TEN

CHAPTER ELEVEN

CHAPTER TWELVE

PART IV: Dragon Passant

CHAPTER THIRTEEN

CHAPTER FOURTEEN

CHAPTER FIFTEEN

CHAPTER SIXTEEN

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN

PART V: Dragon Courant

CHAPTER EIGHTEEN

CHAPTER NINETEEN

CHAPTER TWENTY

CHAPTER TWENTY-ONE

PART VI: Dragon Combatant

CHAPTER TWENTY-TWO

CHAPTER TWENTY-THREE

CHAPTER TWENTY-FOUR

CHAPTER TWENTY-FIVE

PART VII: Dragon Regardant

CHAPTER TWENTY-SIX

AUTHOR’S NOTE

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Back series promotional page

PART I

White Dragon

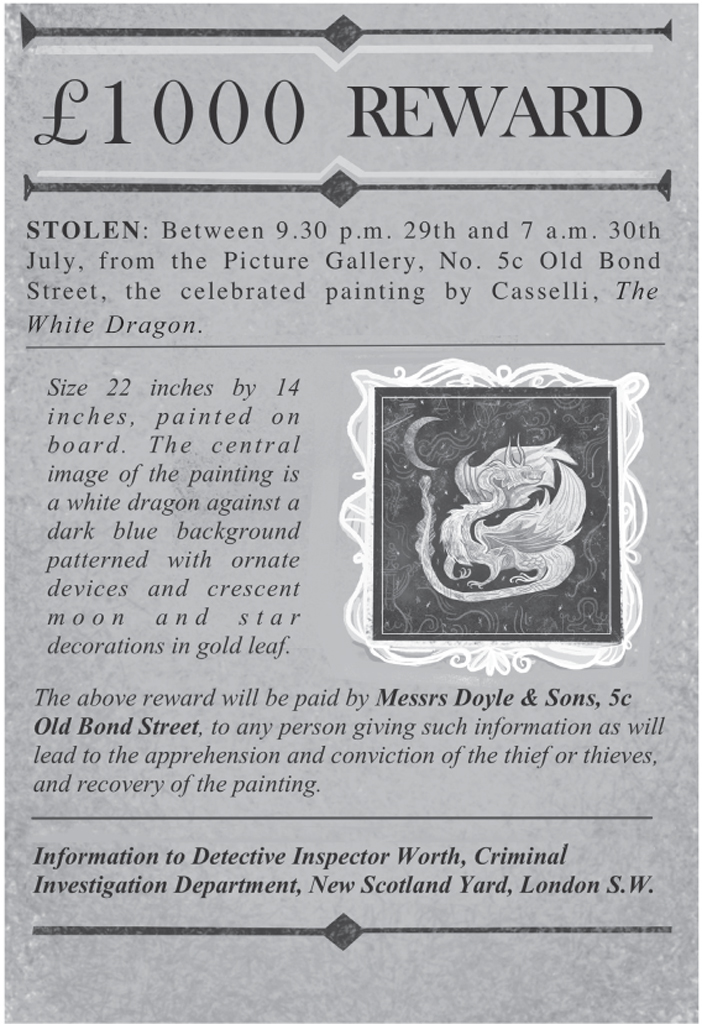

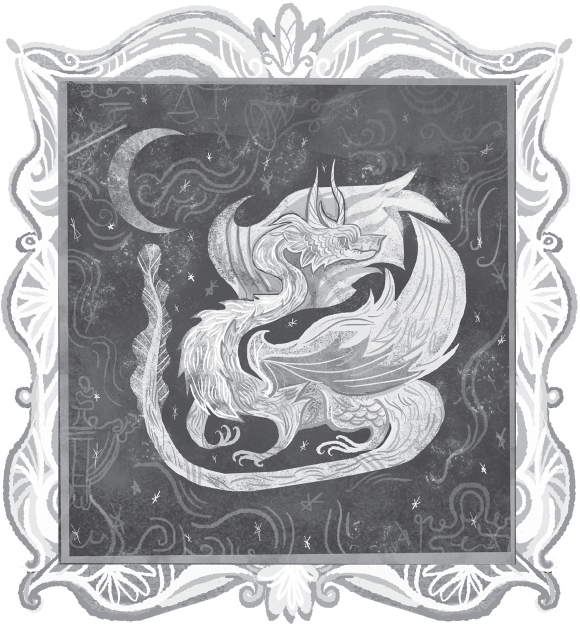

Visitors to London’s Bond Street galleries should not miss works such as Casselli’s The White Dragon, currently on display at the Doyle Gallery. This exquisite example of Italian painting has a fascinating history, having been owned by many of the crowned heads of Europe, including Philip II of Spain and Catherine the Great . . .

From Chapter IV of A Traveller’s Guide to London with 4 Maps and 15 Plans by the Reverend Charles Blenkinsop, 1906 (from the library at Winter Hall)

CHAPTER ONE

October 1909

She wasn’t sure exactly when she realised that someone was following her. The interview with Detective Worth had taken longer than she had expected, and when she stepped out on to the street, it was already dark. The daytime crowds had vanished and Piccadilly seemed unnaturally quiet, with only a few figures hurrying by in the rain, their faces hidden beneath their umbrellas.

In a different mood, she might have thought that the way the yellow light from the street lamps shimmered on the wet road was beautiful. She might have wondered about how she could paint the hazy reflections in the shop windows, or the headlamps glowing in the dark. But for once, she was not thinking about painting. She was too distracted by her conversation with Detective Worth to pay attention to anything around her.

The evening air was cold and dank: she found herself shivering in spite of her good coat. She thought longingly of tea and a warm fire, but she dared not hurry home too quickly – the pavement was slick with water, and slippery with damp leaves. Instead, she slowly picked her way towards the underground railway station.

When she became aware of the man walking behind her, she had the feeling that he must have been there for some time. Lost in her thoughts, sounds muffled by the rain, she had not noticed his presence. Now, she glanced up into a darkened shop window and saw his reflection for a split second: a shadowy shape with square shoulders and the outline of a bowler hat. He was a few yards behind, keeping pace with her – she could hear the regular rhythm of his footsteps. All at once, she felt the creeping sensation that there were eyes fixed upon her back.

She shook herself. She was being stupid, she squashed down the impulse to turn around and look. He was probably just some ordinary man leaving his office late after a long day. To prove it to herself, she made up her mind to cross the road, feeling sure that he would not follow. There, she told herself triumphantly, as she made her way across the street, and on to the opposite pavement. She knew she had been imagining things. The interview with Detective Worth had rattled her, that was all.

For a few yards, she walked more easily. But a moment or two later, she heard it behind her again: the steady beat of footsteps. A chill swept over her. The man was still there.

She couldn’t help glancing over her shoulder now, but in the darkness all she could see was the silhouette of the bowler hat moving towards her. Alarmed, she turned and crossed the street again: a minute later, the man followed. Her heart had begun to thump painfully in her chest, and her breaths were quick and sharp. She hurried on, as quickly as she dared, but the footsteps just seemed to grow louder. She went faster, panic rising, sure of nothing except that she must get away.

As she drew closer to the station, the street became busier, and she saw to her relief that a little crowd of people had gathered outside a brightly lit concert hall. The evening performance was about to start: there were motor cars and hansom cabs outside, and the sound of voices and music. She made her way into the crowd, weaving her way through the mass of people, and then out again, on to the street beyond, red-cheeked and panting – but alone.

Just around the corner was the entrance to the underground station. She hurried thankfully down the steps and out of the rain, her heart still bumping, fumbling for her ticket with shaking fingers. She made her way along the empty tiled passageway, moving more slowly now. The sudden quiet was a relief.

There was no one to be seen on the station platform – not even a guard on duty. She stood alone at the edge of the platform, staring up at the big clock, watching the second hand flick forwards. Here, everything seemed ordinary again. The ticking of the clock, the tattered advertisements for Bird’s Custard and Fry’s Milk Chocolate, the colourful poster instructing her to ‘Take the Two-Penny Tube and Avoid All Anxiety!’ were soothing. Her breathing began to slow. She almost began to wonder if she had imagined the man in the bowler hat was following her, after all.

She felt more tired than ever now, and she stared down the tunnel into the darkness beyond, willing a train to appear. But even as she did so, she heard it again: the heavy, hollow thud of footsteps approaching along the empty platform.

There was no time to turn around; no time to think; no time even to scream. The man was behind her; she felt the scratch of his rough coat sleeve, the cold leather of his gloved hand, pressed hard and shiny across her mouth, silencing her before she could make a sound.

Even as she tried to twist away, she knew it was hopeless. The leather glove covering her mouth was scarlet: the bold cadmium red of her paintbox. It was the last thing she saw clearly before he pushed her. There was a clatter and a gasp, and she was falling through the air for a moment, landing on the train tracks with a sickening thump – then everything was still.

She groaned. Her eyelids fluttered. She was sprawled painfully across the tracks: she could feel the hard metal rail pressed against her side. Before her, the dark mouth of the railway tunnel yawned open, vast and pitch black. Then came a flicker of light ahead – and the scream of a train, rushing out of the tunnel towards her.

CHAPTER TWO

Three months earlier – July 1909

The letter was lying on the silver tray on the hall table when she came down to breakfast. A narrow white envelope with her name, Miss Leonora Fitzgerald, typed at the top. The sight of it made her mouth suddenly dry, and her chest squeeze tight. She knew there was only one thing it could be.

She reached for the envelope, but before she could take it, Vincent came swaggering into the hall, still doing up the studs on his collar. She snapped her hand back at once, but it was too late.

‘What’s this? A letter – for you?’ He grabbed for it, but Leo shot out her hand and snatched it up first. She might not be very fast on her feet, but she had learned to be quick in other ways.

‘That’s mine,’ she said. She began to back away, but Vincent stepped forwards and seized her wrist.

‘I know what that is,’ he said, his voice triumphant. ‘That’s a letter from your little art school, isn’t it? Let me guess what it says: Dear Miss Fitzgerald, We are terribly sorry but we can’t accommodate talentless lady daubers at our establishment.’ He twisted her wrist hard and Leo gasped, but she kept clutching the letter. ‘Shall we have a look and see?’

To her enormous relief, just then, she heard the jingling of the housekeeper’s keys: Mrs Dawes was coming along the corridor towards them. Scowling, Vincent let go of her wrist, and Leo shoved the letter into the pocket of her frock, darting down the passage and away.

Breakfast didn’t matter. She was too excited to eat anyway, and it wasn’t as though her absence would bother anyone. Most days Father barely grunted at her from behind the newspaper; and as for Mother, she always took her breakfast in bed, then spent the morning relaxing in her room. The main thing was to get as far away from Vincent as fast as she could, so she could open her letter in peace.

She slipped around a corner where an old tapestry hung on the wall, woven with a design of lions and unicorns. Glancing quickly around her to be sure that Vincent hadn’t followed, she lifted up one corner, revealing a small door in the wooden panelling. A moment later, she was through the door and into the narrow, stone-flagged passageway that lay beyond, letting the tapestry fall back across the door behind her.

Winter Hall was an enormous old mansion, rich in secret stairways, forgotten cubbyholes and concealed corridors that no one seemed to know or care about, except for Leo herself. These hidden passageways had fascinated her for as long as she could remember – but what’s more, they came in useful. This wasn’t the first time they’d helped her escape from her family.

Now, she made her way carefully along the crooked passage, and then up a skinny staircase. There was a hidden room tucked away at the top that was one of her favourite corners, which she had furnished with an old chair and an oil lamp. She kept her sketchbooks there, away from Vincent’s prying eyes, as well as a collection of objects that were interesting to draw, but that Nanny would certainly say were ‘nasty old rubbish’: some pieces of wood twisted into interesting shapes; a couple of small animal skulls that she had picked up on her walks in the grounds; an abandoned bird’s nest.

Safe at last, she felt able to take out her letter – a little crumpled from being stuffed into her pocket, but no less precious for that. She held it for a moment, weighing it in her hands, and then she ripped it open, drawing out the thin sheet of typed paper inside.

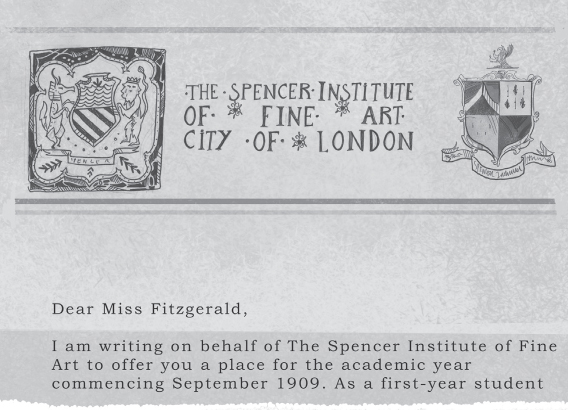

The rest of the words swam in front of Leo’s eyes: she couldn’t take them in. She sank into the chair, the letter fluttering down into her lap. She had actually done it. She had been accepted to the best art school in London!

It still seemed incredible that she had been allowed to apply to the Spencer at all. She had been begging Father and Mother to let her go to art school for more than a year, but they had barely listened, while Vincent had scoffed and jeered. Even Nanny had said ‘nonsense’ and that such places weren’t for young ladies. If it hadn’t been for Lady Tremayne, she doubted that any of them would ever have taken her seriously.

Lady Tremayne was Leo’s godmother. She was an old friend of Mother’s, a wealthy widow who lived in London, and who seemed to Leo to be unimaginably sophisticated. She always wore wonderful clothes: gracefully draped dresses in jewel colours; embroidered silk shawls; gorgeously feathered hats. She talked of the writers and musicians she knew; the art galleries and concert halls she visited; the new books she had read.

Lady Tremayne was the only one who cared about Leo’s passion for drawing. Mother just said ‘very nice, dear’ in a bored voice; while Nanny grumbled that the charcoal marks on her muslin frock were dreadful to get out, and suggested she might like to learn some nice embroidery stitches instead. But Lady Tremayne was different. On her all-too-rare visits to Winter Hall, she always asked to see Leo’s sketchbooks; and sometimes she even brought her presents – pencils, a new drawing book with lovely paper inside, once a little set of watercolour paints in a neat leather case.

It was to Lady Tremayne that Leo had been able to pour out her dream of going to a London art school. She longed to learn from proper teachers; to work in a real artist’s studio; and perhaps most of all, to see London and explore its wonderful galleries and museums. She had told all this to her godmother, who had promised she would try to help.

Leo was not supposed to have heard Lady Tremayne’s conversation with Mother, but it had been an easy thing to listen in from the secret passage with its discreet ‘peephole’ that ran behind the boudoir sitting room. Leo knew that she ought not to eavesdrop on other people’s conversations, but any sense of guilt she might have felt was swept away, as she realised what her mother was saying in her high, whining voice.

‘The truth is that I haven’t the slightest idea what to do with her. She’s so sulky and difficult. I never had any of these troubles with Helen!’

‘Leo’s growing up,’ came Lady Tremayne’s voice, clearer and deeper. ‘She needs something to occupy her. Don’t forget, at her age, Helen was busy planning her coming-out ball, and getting ready for her first Season.’

‘But whatever am I to occupy her with?’ Leo’s mother demanded, sounding even more petulant than usual. ‘A London Season is quite out of the question for her. If she was a different sort of girl, I suppose I might have taken her abroad with me this autumn, but Horace doesn’t like her to be on show. She doesn’t care for society, and she doesn’t take any interest in anything except fiddling around with pencils and paint – and this preposterous idea of going to a London art school.’

‘It’s more than just fiddling, Lucy. Leo has a real talent – I’ve always thought so. Are you so sure that art school is out of the question for her?’

‘Really, Viola! Art school! She couldn’t possibly – what would people think? We couldn’t allow her just to racket about London, all by herself!’

Mother’s voice was shocked, but Lady Tremayne laughed. When she spoke, her voice was warm and amused: ‘Oh, Lucy, don’t be so old-fashioned! She’d be far too busy for any racketing. Why, at the Spencer Institute they have drawing classes every day, and then there are lectures and museum visits. It would be good for Leo to have that sort of occupation, and to meet other young people who share her interests. Far better than moping around here, with only her old nanny for company.’

Mother sighed heavily. ‘I suppose you’re right. Something ought to be arranged. Perhaps a good finishing school might help to rub off her corners?’

Leo’s heart sank to her stomach, but Lady Tremayne had not given up. ‘Finishing school?’ she repeated. ‘I hardly think dancing and deportment are going to be of any use to Leo! Art school would be a much better use of her time. They are perfectly respectable places these days – after all, the Duke of Roehampton’s sister went to the Spencer, you know.’

Leo smiled to herself in the dark. Her mother’s sudden little sound of interest and approval did not surprise her in the least. ‘Oh! Did she really? I had no idea!’

Evidently aware she had an advantage, Lady Tremayne continued: ‘So, you see, it couldn’t possibly do Leo any harm. Perhaps she may become a little more unconventional, but that doesn’t really matter, does it? After, all, it’s not as if . . .’

Her godmother’s voice trailed away, but Leo could have finished the sentence for her. It’s not as if she will marry. Suddenly feeling that she didn’t want to hear any more, Leo turned away from the peephole.

Marriage was something that girls from a good family were supposed to do. It was all that was expected of them – to look pretty, to be charming, and then to eventually marry a ‘suitable young man’ and produce lots of children, exactly like her perfect older sister Helen had done.

But Leo knew that no ‘suitable young man’ would ever want to marry her. For one thing, she was not in the least bit pretty. Pretty girls had curls and rosy cheeks and dimples; Leo was thin and pale, and her hair hung straight and smooth, refusing to curl in spite of Nanny’s best efforts. Pretty girls dressed in dainty gowns with ribbons and lace trimmings. Leo preferred plain things: as a child she had always looked enviously at Vincent’s clothes, admiring the smart cut of his velvet jackets, the shiny leather of his riding boots. Mother had been horrified when she had asked why she couldn’t dress like her brother, and Nanny had told her to ‘hold her tongue’ and to ‘act like a little lady’.

What’s more, she knew she wasn’t charming. She had always spent so much time alone that she never seemed to know what to say to people. Then, just before her eighth birthday, she had been ill, and that had changed everything. The long illness had confined her to bed for months. One of her legs had been badly affected; they had thought she might never walk again but she had been determined, and at last she had been able to manage with the help of a crutch. It was this, of course, that Lady Tremayne was referring to. Far more important than being pretty, marriageable young ladies were expected to be perfectly healthy: as glossy and energetic as prize racehorses. They could not possibly have what Mother referred to, in a hushed voice, as an affliction.

But it had been when she was ill in bed that Leo’s drawing had really begun. She had spent hours drawing anything and everything she could see: Nanny, the medicine bottles by the window, the view of leafless trees outside. When she had at last been able to hobble about the house, she had amused herself by exploring the long passageways, opening doors on neglected rooms and drawing what she found there. She spent hours contemplating strange old oil paintings, sketching the shapes of Chinese vases and marble statuettes, copying the intricate patterns of old carpets, and later painting her own careful imitations of the portraits of her Fitzgerald ancestors.

‘Of course, the Spencer is very competitive,’ Leo heard Lady Tremayne say, as she turned back to the peephole. ‘It’s the finest school in the country – they take only the very best.’

‘She probably wouldn’t even be able to win a place,’ said Mother, more comfortably. ‘I suppose I’ll speak to Horace about it – perhaps he may consent to her writing to them. But really, Viola, that’s quite enough about the matter. I’m longing to hear about your trip to Vienna – is the opera as splendid as they say?’

Now, remembering this, Leo felt hot inside. She knew that Mother had never believed she stood even the slightest chance of winning a place at the Spencer – but she had been accepted. The Spencer Institute of Fine Art, she read again, tracing her fingers along the shape of the letterhead, and murmuring the words to herself as though they were a magic spell. She couldn’t wait to write to Lady Tremayne to tell her the news.

But first, she had work to do. She grabbed her crutch and pulled herself to her feet. She was going to the Spencer, and she would not let Mother or Father or anyone else stand in her way. Moving quickly, she made her way along the secret passageway, and back out into the corridor. So much for Mother’s relaxing breakfast in bed, she thought grimly. She pushed open the door to Mother’s bedroom. ‘Mother!’ she announced. ‘The Spencer Institute have written – and I’ve got in!’

CHAPTER THREE

September 1909

It was a wet afternoon in London, and on Piccadilly Circus the windows of Sinclair’s seemed to shimmer. The city’s most famous department store spilled out golden light on to the dull grey street. The people hurrying by under their umbrellas were unable to resist pausing for a moment to look at the glittering displays of glorious autumn fashions in the store window, or to peep through the grand entrance, at the throng of elegant shoppers within.

Up the steps and through the great doors, the store was warm and inviting, delicious with the fragrance of chocolate and warm caramel that drifted from the Confectionery Department. Customers were dawdling in the Book Department, flicking through the latest novels, or dallying in Ladies’ Fashions, taking their time to choose exactly the right fur tippet, or silk umbrella. Meanwhile, others simply luxuriated in the thick softness of the carpets and the glitter of the chandeliers, watching the people go by. There was always something – or someone – to watch, at Sinclair’s.

No one knew that better than Sophie Taylor. But that afternoon, she was walking swiftly past the store windows, without even a glance at the brightness within. Today, she was quite unrecognisable as a smart salesgirl from the Millinery Department. Her fair hair was windblown; her frock was streaked with mud; her buttoned boots were dirty; and her thin coat did little to keep off the rain. In fact, she was so bedraggled that one or two people looked askance as she came through the door of Lyons Corner House. Holding her head high, and ignoring their curious glances, she dripped over to a corner table for two, spread with a white cloth and laid for tea. She dropped down into a chair with relief.

‘Tea, miss?’ asked the waitress hovering at her elbow.

Sophie looked up at her with a rueful smile as she peeled off her sodden gloves. ‘Yes please,’ she said. ‘Tea would be heavenly.’

The pot was almost empty when the door opened again, and a young lady hurried in. She was tall and striking, snug in a smart blue coat with a velvet trim. A matching hat with a crest of feathers was pinned at a dashing angle upon her shiny dark hair. She was not dressed expensively, nor in the very latest fashion, yet there was something about her appearance that made the tea-shop customers sit up straighter in their chairs. Suddenly, an ordinary wet afternoon seemed tinged with a sparkle of glamour.