Полная версия

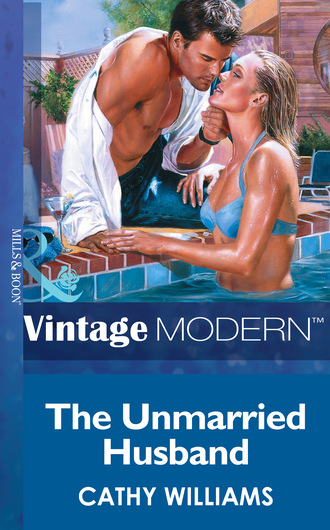

The Unmarried Husband

“You’re damned stubborn,” he murmured.

“If you say so.”

“Yes, I do. Not that you don’t look quite captivating with that pout.”

Had she been pouting? Jessica tried to rearrange her features into some semblance of calm. I’m still furious with you, she thought. I still resent it that you feel you can lecture me on my abilities as a mother—even if what you say is true….

But when she looked down, all she could see was the sprinkling of dark hair on his arms. When she breathed, she breathed in the aroma of his maleness. It was powerful, disorienting.

And she knew, before he kissed her, exactly what he was going to do.

CATHY WILLIAMS is Trinidadian and was brought up on the twin islands of Trinidad and Tobago. She was awarded a scholarship to study in Britain, and went to Exeter University in 1975 to continue her studies into the great loves of her life: languages and literature. It was there that Cathy met her husband, Richard. Since they married, Cathy has lived in England, originally in the Thames Valley but now in the Midlands. Cathy and Richard have three small daughters.

The Unmarried Husband

Cathy Williams

MILLS & BOON

Before you start reading, why not sign up?

Thank you for downloading this Mills & Boon book. If you want to hear about exclusive discounts, special offers and competitions, sign up to our email newsletter today!

SIGN ME UP!

Or simply visit

signup.millsandboon.co.uk

Mills & Boon emails are completely free to receive and you can unsubscribe at any time via the link in any email we send you.

CONTENTS

CHAPTER ONE

CHAPTER TWO

CHAPTER THREE

CHAPTER FOUR

CHAPTER FIVE

CHAPTER SIX

CHAPTER SEVEN

CHAPTER EIGHT

CHAPTER NINE

CHAPTER TEN

CHAPTER ONE

THERE was the sound of the front door being opened and shut, very quietly, and Jessica woke with a start. For a few seconds she experienced a feeling of complete disorientation, then everything resettled into its familiar outlines.

She waited, motionless, in her chair, which had been soft enough for her to fall asleep on but too soft to guarantee comfortable slumber, so that now the back of her neck hurt and her legs needed stretching.

She watched as Lucy tiptoed past the doorway, and then she said sharply, ‘What time do you call this?’

Captured on film, it would have been a comic scenario. The darkness, the stealthy figure creeping towards the stairs, the piercing ring of a voice shocking the figure into total immobility.

Unfortunately, Jessica Hirst didn’t find anything at all funny about the situation. She hated having to lie in wait like this, but what else could she do?

‘Oh, Mum!’ Lucy attempted a placating laugh, which was too nervous to be credible. ‘What are you doing up at this hour?’

‘It’s after two in the morning, Lucy!’

‘Is it?’

‘It most certainly is.’

‘But tomorrow’s Saturday! I don’t have to get up early for school!’

Lucy switched on the light in the hall, and the dark shape was instantly transformed into a sixteen-year-old teenager. An extremely pretty sixteen-year-old teenager, with waist-length dark hair and hazel eyes. The gauche body of two years ago had mellowed into a figure, so that the woman could easily be discerned behind the fresh-faced child.

Where had the years gone? Jessica straightened in her chair, quite prepared to have this one out here and now, even though she felt shrewish and sleepy, and depressingly like the stereotyped nagging mum.

‘Come in here. I want to have a word with you.’

‘What, now?’ But Lucy reluctantly dragged her feet into the sitting room, switching on the overhead light in the process, and slumped defensively into the chair opposite her mother. ‘I’m really tired, Mum.’

‘Yet not so tired that you couldn’t find your way home earlier?’ Don’t raise your voice, she told herself, try to sound reasonable. Treat her the way you’d treat a possibly unexploded bomb. It seemed odd, though, because she could still remember a squawking, red-faced baby in nappies. And now here she was, sixteen years later, having it out with a rebellious teenager who at times might well have been a stranger. She couldn’t quite put her finger on when this transformation had taken place, but certainly in the last few months Lucy had altered almost beyond recognition.

Lucy sighed and threw her a mutinous look. ‘I’m not a child, Mum.’

‘You are a child!’ Jessica said sharply. ‘You’re sixteen years old…’

‘Exactly! And capable of taking care of myself!’

‘Do not interrupt me when I’m talking to you!’ Which brought another mutinous glare from under well defined dark brows. ‘You told me that you would be back by eleven.’

‘Eleven! None, but none of my friends have to be home by eleven! Anyway, I had every intention of getting back here by then. It’s just that…’

‘Just that what?’

‘You’re shouting.’

‘I have every reason to shout!’ She wanted to march over to the chair and forcibly shake some common sense into her daughter’s head. ‘Lucy,’ she said wearily, ‘you’re too young to be out and about at these sorts of hours in London.’

‘I wasn’t “out and about” in London, Mum. You make it sound as though I’ve been walking the streets! We went to watch a video at Kath’s house, and then afterwards…’

‘And then afterwards…?’ Jessica could feel her stomach going into small, uncomfortable knots. She knew that in a way she was lucky that Lucy would at least still sit and talk to her, where some others might just have stormed off up to bed and locked the door, but that didn’t stop her mind playing its frantic games.

She had read enough in the newspapers to be all too aware of the dangers out there. Drugs, drink, Lord only knew what else. Was Lucy sensible enough to turn her back on all of that? She thought so, she really did. But then, at two-thirty in the morning, it was difficult to cling onto reason.

‘Well, we went over to Mark Newman’s house.’ Lucy glanced sheepishly at her mother. ‘I wouldn’t have gone,’ she mumbled, ‘but Kath wanted to go, and Mark promised that he’d give me a lift back here. I didn’t want to get the underground back.’

As if that made it all right.

‘I gave you money for a taxi.’

‘I spent it on renting the videos.’

‘You spent it on renting the videos.’ Jessica sighed, feeling as though she was battling against a brick wall. ‘Wasn’t that a little short-sighted, Lucy?’

Lucy fidgeted and glared, and then muttered something about her pocket money being inadequate.

‘Inadequate for what?’ Jessica asked tersely, which met with no response this time at all. ‘I can’t afford to throw money at you, Lucy. I thought you understood that. There’s the mortgage to pay off, bills, clothes, food…’

‘I know.’

Lucy knew, but Jessica could tell from that tone of voice that knowing and accepting were two different things, and she could feel tears sting the backs of her eyes. Did Lucy imagine that she was economical because she wanted to be?

‘You could have telephoned me,’ she said eventually. ‘I would have come to collect you.’

No response. Lately this had been Lucy’s way of dealing with all unpleasant discussions between them. She simply switched off.

‘So Ruth let Katherine go?’ Jessica asked eventually.

‘She wasn’t there,’ Lucy admitted uncomfortably. ‘She and Mike have gone to visit some relative or other who’s recovering from a stroke.’

‘So who was there? Who gave you permission to go to this boy’s house? At that hour of the night!’

‘Her brother said it’d be all right. I don’t know why you’re in such a state about this, Mum!’

‘Mark Newman… You’ve mentioned that boy’s name in the past. Who is he?’ She decided, reluctantly, to let the question of permission from an adult drop. She didn’t see that it would get either of them anywhere.

Instead she frowned, concentrating on the familiar sound of that name, realising with a jolt that it had been on Lucy’s lips ever since her daughter had started being more interested in parties than in studying. Who the heck was Mark Newman? No one from her class, certainly. She knew the names of all the children in Lucy’s class, and that wasn’t one of them.

She swallowed back visions of beards, motorcycles and black leather jackets with names of weird rock groups embroidered on the back.

‘Well? Who is he, this Mark Newman character?’ Jessica repeated sharply. ‘Precisely?’

‘No one important,’ Lucy said flippantly, eyes diverted, so that Jessica instantly smelled a rat.

‘And where does this child live?’

‘He’s not a child! He’s seventeen, actually.’

Oh, God, Jessica thought. An out of work labourer with nothing better to do than prey on young, vulnerable girls like Lucy. Probably a drug pusher. Oh, God, oh, God, oh, God. She could feel her hands, tightly clenched, begin to tremble.

‘And what do his parents have to say about this? Turning up at their house with a horde of young girls in tow?’ Why am I mentioning parents? she thought. He probably lives in a squat somewhere and hasn’t seen his parents in years.

‘There’s only his dad, and he’s never at home. And there weren’t hordes of young girls in tow. Just Kath and me.’

‘And where, precisely, is home?’

‘Holland Park.’

Which silenced some of the suspicions, but only momentarily. Holland Park might not be a squat in the bowels of the East End, but that said nothing.

‘Lucy,’ she said quietly, ‘I know you’re growing up, getting older, but life in the big, bad world can be dangerous.’

‘Yes. You’ve told me that before, Mum.’ Lucy looked down, so that her long hair swung around her face like two dark curtains, hiding her expression.

Whoever this Mark Newman was, couldn’t he see that she was just a child? Younger than he was, for heaven’s sake, and with a fraction of the experience, for all the obligatory black clothes and strange black boots, which Jessica had tried to talk her out of buying!

Her mind accelerated towards thoughts of sex, and skidded to a halt. She just couldn’t think of Lucy in terms of having sex with someone.

‘Boys, parties…all that can wait, Luce. Right now, you’ve got your studies. Exams are just around the corner!’

‘I know that! As if you ever let me forget!’

‘And I don’t suppose it’s occurred to you that a little study might go a long way towards your passing them?’ She could hear her voice raised in alarm at the possibility of her daughter rejecting academic education in favour of education of a different sort. Under the influence of the likes of Mark Newman.

‘Can we finish this in the morning? I’m really tired.’

‘Do you imagine that you will ever be able to do anything with your life without qualifications?’

‘You keep going on about this.’

‘Because it’s important! Because it’s the difference between going somewhere and remaining rooted to…to this…!’ She spread her hands expansively, to encompass the small sitting room.

Do you want to end up like me? she wanted to cry out. I made my mistakes, and I’ve spent a lifetime paying for them.

She didn’t want her daughter to go the same way.

But Lucy had switched off. Jessica could see it in the blank expression on her face. The conversation would have to be continued the following day, a semipermanent onslaught which she hoped would eventually have the effect of water dripping on a stone.

‘Go to bed, love,’ she said in a tired voice, and Lucy sprang up as though she had been waiting for just such a cue. ‘Lucy!’

The slender figure paused in the doorway, looking back over one shoulder.

‘I love you, darling. That’s the only reason I say these things. Because I care.’ She felt choked getting the words out, and once out they barely seemed to skim the depth of emotion she felt towards her daughter.

‘I know, Mum.’ There was a glimmer of a smile, a bit of the old Luce coming out. ‘Love you, too.’

It was after four by the time Jessica was finally in bed, but her thoughts would not let her get to sleep.

Every time she played over these arguments with her daughter in her head she thought back to those days of innocence, when watching Lucy growing up had been like watching a flower unfolding, each stage as fascinating and as beautiful as the one before. First smile, first step, first word, first day at school. Everything so new and uncomplicated.

Just the two of them, locked in a wonderful world. It was easy to forget all the bad times before.

She closed her eyes and realised that it had been a very long time since she had dwelled on the past. It was strange how the years blunted the edges of those disturbing times, until memories of them turned into fleeting snapshots, still sharp but without the power to hurt.

She could have been something. Something more than just a secretary working in a law firm. It didn’t matter that they gave her a lot of responsibility, that they entrusted her with a great deal of important work. It didn’t even matter that she had picked up enough on the subject to more than hold her own with most of the junior lawyers in the firm.

No. But for circumstances, she could have been one of them. A barrister. Well-read, treading a career path, moving upwards and onwards. Qualified.

Lucy might not appreciate the importance of completing her education, but Jessica was damned if she would let opportunity slip through her daughter’s fingers the way that it had slipped through hers.

Mark Newman. The name that had cropped up on several occasions. She racked her brains to try and locate when that name had first been mentioned. Had Lucy mentioned anyone else’s?

Jessica couldn’t remember, but she didn’t think so. No, Lucy had been happily drifting through with her schoolfriends, and her only show of rebellion had been her rapid change of dress code, from jeans and jumpers to long black skirts and flamboyant costume jewellery.

She could remember laughing with Kath’s mum at the abrupt transformation, astonished at how quickly it had marked the change from girl to teenager, quietly pleased that really there was nothing for her to worry about.

How on earth could she have been so complacent? Allowed herself to think that difficult teenagers were products of other people? That her own daughter was as safe as houses?

Her last thought as she drifted into sleep was that she would have to do something about the situation. She wasn’t going to sit back and let life dictate to her. She would damn well do the dictating herself.

It was only on the Sunday evening, after she had made sure that Lucy sat down with her books, after she had checked her work, knowing that her efforts at supervision were tolerated, but only just, after she had delivered several more mini-lectures on the subject of education—after, in fact, Lucy had retired to bed in a fairly good mood despite everything—that the idea occurred to her.

No point fighting this battle single-handedly.

She could sermonise until she went blue in the face, but the only way she could get Lucy back onto the straight and narrow would be to collect her from school and then physically make sure that she stayed rooted inside the house.

It was an option that she shied away from. Once down that particular road, she might find the seeds she had sown far more dangerous than the ones she was hoping to uproot.

No, there was a better way. She knew relatively little about Mark Newman, but she knew enough to realise that he was an influence over Lucy.

And Mark Newman had a father.

She doubted that she could appeal to the boy’s better instincts. A seventeen-year-old who saw nothing wrong in keeping a child of sixteen out until two in the morning probably had no better instincts.

She would go straight to the father.

Naturally, Lucy couldn’t be told. Jessica felt somewhat sneaky about this, but in the broader scheme of things, she told herself, it was merely a case of the end justifying the means.

Nevertheless, at nine-thirty, when she picked up the telephone to make the call, the door to the sitting room was shut and she knew that she had the studied casualness of someone doing something underhand.

It hadn’t helped that the man was ex-directory and she had had to rifle through Lucy’s address book to find the telephone number.

She listened to the steady ringing and managed, successfully, to persuade herself that what she was doing she was doing for her daughter’s sake. Most mothers would have done the same.

The voice that eventually answered snapped her to attention, and she straightened in her chair.

‘May I speak to Mr Newman, please?’

‘I’m afraid he’s not here. Who’s calling?’

‘Can you tell me when he’ll be back?’

‘May I ask who’s calling?’

‘An old friend,’ Jessica said, thinking on her feet. No point launching into an elaborate explanation of her call. She had no idea whose voice was at the other end of the phone, but it sounded distinctly uninviting. ‘I haven’t seen Mr Newman for years, and I just happened to be in the country so I thought I’d give him a ring.’

‘May I take your name?’

‘I’d prefer to surprise him, actually. He and I…well, we once knew each other very well.’

It suddenly occurred to her that there might be a Mrs Newman on the scene, but then she remembered what Lucy had said—‘there’s only his dad’—and she must be right, because the voice down the line lost some of its rigidity.

‘I see. Mr Newman should be back early tomorrow morning. He’s flying in from the States and going straight to work.’

Jessica chuckled in a comfortable, knowing way. ‘Of course. Well, he hasn’t changed!’ It was a good gamble, and based entirely on the assumption that men who travelled long haul only to head straight to the office belonged to a certain ilk.

‘Perhaps you could tell me where he works? It’s been such a while. I’m older now, and the memory’s not what it used to be. Is he still…where was it…? No, just on the tip of my tongue…” She laughed in what she hoped was a genuine and embarrassed manner, feeling horribly phoney.

‘City.’ The voice sounded quite chummy now. He rattled off the full address which Jessica dutifully copied down and secreted in her handbag.

And tomorrow, Mr Newman, you’re in for a surprise visit.

At ten past ten on Sunday evening, sleep came considerably easier.

She made her way to the City offices as early as she could the following morning, after a quick call to Stanford, James and Shepherd, telling them that she needed to have the day off because something unexpected had turned up, and then the usual battle with the underground, packed to the seams because it was rush hour and coincidentally heading into the height of the tourist season.

She had dressed for the weather. A sleeveless pale blue dress, flat sandals. Yet she could still feel the stifling heat seeping into her pores. Temperatures, the weather men had promised, were going to hit the eighties again. Another gorgeous cloud-free day.

She wished that she could close her eyes and forget all these problems. Go back to a time when she’d been able just to whip Lucy along to the park for a picnic, when the nearest thing to defiance had been a refusal to eat a ham sandwich.

She allowed herself to travel down memory lane, and only snapped back to the present, with all its worrying problems, when her destination confronted her—a large office block, all glass and chrome, like a giant greenhouse in the middle of London.

Inside it bore some resemblance to a very expensive hotel foyer. All plants and comfortable sitting areas and a circular reception desk in the middle.

Jessica bypassed that and walked straight to the lifts. She knew what floor the Newman man was located on. She had managed to prise that snippet of information from the unwelcome recipient of her phone call the evening before, still working on the lines of the wonderful surprise she would give him by turning up, and shamelessly using a mixture of charm and flirtatiousness to wheedle the information from him.

The man, she had thought since, would never have made a security guard. Did he dispense floor numbers and work addresses to every caller who happened to telephone out of the blue and claim acquaintanceship with his employer?

But she had been grateful for the information, and she was grateful now as the lift whizzed her up to the eighth floor.

Receptionists, she knew from first-hand experience, could be as suspicious as policemen at the scene of a crime, and as ruthless in dispatching the uninvited as bouncers outside nightclubs. Paragons or dragons, depending on which side of the desk you were standing.

Stepping out on the eighth floor was like stepping into another world.

There was, for starters, almost no noise. Unlike the offices where she worked, which seemed to operate in a permanent state of seemingly chaotic activity—people hurrying from here to there, telephones ringing, a sense of things that should have been done sooner than yesterday.

The carpet was dull green and luxuriously thick. There was a small, open-plan area just ahead of her, with a few desks, a few disconcertingly green plants, and secretaries all working with their heads down. No idle chatter here, thought Jessica, trying to think what this said about their bosses. Were they ogres? Did they wield such a thick whip that their secretaries were too scared to talk?

She slipped past them, down the corridor, passing offices on her left and pausing fractionally to read the name plates on the doors.

Anthony Newman’s office was the very last one along the corridor.

Strangely, she felt not in the least nervous. She had too many vivid pictures in her head of her daughter being led astray by the neglected son of a workaholic for nerves to intrude. If people couldn’t rustle up time for their children, then as far as she was concerned they shouldn’t have them.

She knocked on the door, not in the least anticipating that the workaholic Newman person might be involved in a meeting somewhere else, and her knock was answered immediately.

Jessica pushed open the door, hardly knowing what to expect, still fuelled by a sense of fully justified parental concern, and was immediately confronted by a large expanse of carpet, an imposing oak desk, and behind that a man whose initial appearance momentarily made her stop in her tracks.

The man was on the phone. His deep voice was barking orders down the line. Not loudly, but with a certain emphatic quietness that made some of her sense of purpose flounder.

She looked at him as he gestured to her to take a seat, and was unwillingly fascinated by the curious, disorientating feeling of power and authority he seemed to give off.

Had she been expecting this? She realised that at the back of her mind she had anticipated someone altogether less forbidding.

It was only when she was seated that she became aware that he was watching her with an equal amount of curiosity. He continued talking, but his cool grey eyes were focused on her, and she abruptly looked away and began inspecting what she could see of his office from where she was sitting.

Not much. Not much, at any rate, that didn’t include him in the general picture.

‘Who,’ he said, replacing the telephone and catching her while her attention was focused on a painting on the wall—an abstract affair whose title she was trying to guess—‘the hell are you? What do you want and how were you allowed into my office?’