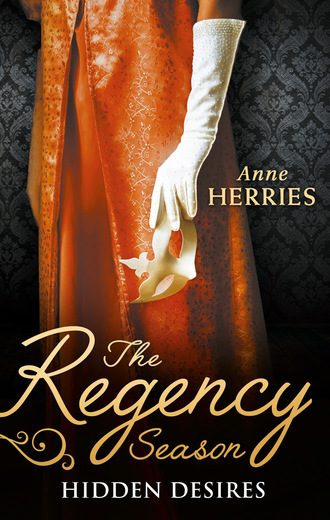

Полная версия

The Regency Season: Hidden Desires

‘I would not expect her to say anything else,’ Adam said. ‘You need not worry for her too much, sir. I shall take it upon myself to keep the young lady company. When the funeral is over I shall search his rooms for evidence—there may be something in his papers that will help us discover the truth of this terrible business.’

‘Yes, well, I shall leave it all to you and Hallam,’ Lord Ravenscar said. ‘Paul is in dark despair at the moment, but I think he will wish to help as soon as he is able.’

‘Yes, of course. We shall all do our utmost to bring this evil monster to justice, Uncle. I give you my word that if it is possible he will hang for his crimes.’

‘I know I can rely on you all. Now, if you will excuse me, I think I shall sit with Mark again for a while. Lucy ought to rest, but she cannot be brought to leave his side. Perhaps it is the best way for her to grieve, poor lass, but I shall persuade her to her bed as soon as I can.’

‘In the circumstances it is hardly to be expected that she would not be deeply affected. She would have been his wife next month.’

Lord Ravenscar passed a shaking hand over his brow and went away. Adam turned towards the parlour where he knew Miss Hastings to be sitting. Although it had been a warm day the evening had turned chilly and a fire had been lit in the parlour. Pausing on the threshold, Adam was struck by the quiet beauty of the young woman’s face as she sat staring into the flames. A glass of wine and a plate of almond comfits had been placed on a small wine table beside her and she had a book in her hand, but it was clear she had been unable to concentrate. She looked up as he entered the room, inquiry in her steady grey eyes.

‘Mr Miller—is there any news?’

‘I fear not and it may be some time before we can track him down, but I promised my cousin I would do it and I shall,’ he told her. He went forwards to warm himself by the fire as she sat down again. ‘You find us at a very sad time for all concerned, Miss Hastings.’

‘Do please call me Jenny,’ she said. ‘We have gone beyond formality, I think. I feel a part of this family for I grieve sincerely for your loss.’

‘How kind of you.’ Adam inclined his head. ‘How could it be different for at such times we are drawn together in grief. It is all the worse because we had such hopes for the future.’

‘Lucy is distraught,’ Jenny said. ‘I do not know how she can bear it, to be so close to happiness and have it snatched away so cruelly. I am determined to be here when she needs me. I know her mother is close at hand and I dare say she may come—but sometimes it is easier to talk to one’s friends, do you not think so?’

‘Yes, I agree entirely. This terrible tragedy will not change your plans?’

‘Oh, no. I shall stay for Lucy’s sake—and in truth for my own. I should not wish to return to my uncle’s house.’

‘Was he unkind to you?’

‘Not exactly—but he did not treat me just as he ought and I prefer to live at Dawlish for the moment. The family will be in mourning and perhaps there are ways in which I can help.’

‘Lucy will need a companion she can talk to. I dare say she may weep on your shoulder a deal of times.’

‘Then we shall weep together for I find this very sad.’

‘Indeed. I think my grief may ease a little in pursuit of my cousin’s killer. I can do nothing for the moment, but I intend to search him out—whoever he may be.’

‘Do you have a clue?’

‘One of the grooms saw a man running away—a gentleman by his clothes, dark hair and perhaps thirty-something in years.’

‘So many men fit that description. You will need more if you are to find him.’

‘Yes, I fear that is the case. We shall not give up until we catch him. There are ways to draw the devil out, I dare say.’

‘I wish you good fortune,’ Jenny said, and then as they heard voices in the hall she stood up once more and turned towards the door. ‘I believe that is Lady Dawlish...’

She was right for the lady in question surged into the room and opened her arms to Jenny, who went into a perfumed and tearful embrace with every evidence of warmth and affection.

‘Where is my poor darling girl?’ the lady said, sniffing into a handkerchief heavily doused in lavender water. ‘I do not know how she will bear this terrible blow.’

‘She is sitting with Mark,’ Jenny said. ‘I fear she is suffering greatly, ma’am, but we shall help her to bear her grief.’

‘He has gone then...’ Shock was in the lady’s face and she made the sign of the cross over her breast. ‘How terrible for Lord Ravenscar—and my poor child. She was so happy...’

‘Yes, I know. This has been a terrible blow—to lose the man she would have married, her childhood hero...it is devastating.’

‘You will not leave us,’ Lady Dawlish said. ‘My poor child will need you to support her in this her hour of need. I know it will be hard for you and not what was promised.’

‘Do not fear, ma’am. I shall not desert her. Lucy is as dear to me as the sister I never had. You may rely on me to be there for her whenever she needs me.’

‘I was certain I might.’ Lady Dawlish blew her nose. ‘My sensibilities are almost overset. I do not know how I could have borne to see my child in such affliction, but you will be my strength, Jenny. You will help us to face what must be.’

Adam saw that Jenny was well able to cope with the lady’s slightly histrionic behaviour and felt it a good thing that Lucy would not have to rely solely on her mama for support.

He rang the bell and asked for tea to give the distressed ladies some temporary relief and left them to comfort each other. Having remembered that Mark kept some of his belongings in the boot room, he decided to go through the pockets of his greatcoats. There might just be a letter or a note of some kind that would give him a starting point.

Watching Lady Dawlish’s distress and seeing the reflection of it in Jenny’s eyes had affected him deeply. Anger and grief mixed in him, sweeping through him in a great tide.

When he discovered who had murdered his cousin in cold blood he would thrash him to within an inch of his life.

Chapter Four

‘Paul...’ Adam cried as he saw his cousin in the boot room removing the muddy boots he’d worn for riding. ‘Thank God you’re back safe. I was beginning to think you might have come to harm. There is a murderer out there and he might not have finished with this family.’

Paul turned his head to look at him, a glare of resentment in his deep-blue eyes. ‘You’ve changed your tune. Earlier today you thought I’d killed Mark. Do not deny it, for I saw it in your eyes.’

‘You had the shotgun and...’ Adam shook his head. ‘I’m sorry if I doubted you. I know you loved him.’

‘So you damned well should,’ Paul muttered furiously. ‘Yes, I love Lucy and if she’d ever looked at me I should have asked her to marry me—but it was always going to be Mark. I would never have harmed him. You must know it, Adam?’

‘It was just something Mark said.’

‘Explain,’ Paul demanded and Adam told him word for word. He nodded. ‘I see why you might have thought—but I swear it was not me.’

‘Then you must be careful. I came here to go through the stuff Mark keeps here. I cannot search his rooms yet, but I need to be doing something. I want that devil caught, Paul. When I get him I’ll teach him a lesson he’ll not forget before I hand him over to the law.’

‘He won’t live long enough for the law to deal with him if I find him first,’ Paul said and cursed. ‘Mark didn’t deserve this, Adam. It makes me so angry...and it hurts like hell.’

‘Yes, it must. I know. We shall all miss him like the devil.’

‘It’s as if a light has gone out,’ Paul said and dashed a hand across his cheek.

‘We’ll find him,’ Adam promised. ‘We shall search until we find him whoever he is. He will not escape justice.’

‘I shall not rest until he is found.’

‘Nor I.’ Adam had begun to go through the pockets of Mark’s coats. He found an assortment of string, bits of wood and a receipt for two hundred guineas for a new chaise. ‘There is nothing here—unless he fell out with someone over this?’

‘The chaise he bought from Parker? No, nothing wrong there—they were both quite happy with the deal.’

‘Well, we must wait until after the funeral...’

‘Don’t!’ Paul said and struck the wall with his fist. ‘I can’t bear to think of him lying dead in his room.’

‘There is nothing you can do for him except help to find his killer.’ Adam placed a hand on his shoulder, but Paul shrugged it off and strode from the room, leaving him alone. He swore beneath his breath. ‘Damn it...damn it all to hell...’

* * *

‘Miss...Jenny,’ Adam called as he saw her at the bottom of the stairs, clearly preparing to retire for the night. Her air of quiet composure struck him once more. What a remarkable woman she was—an oasis in a desert of despair. ‘Are you all right? Is there anything I can do for you—or Lady Dawlish?’

‘Lady Dawlish is with Lucy for the moment. I am going to the room, which I shall share with Lucy. Her mama is trying to persuade her to rest for a while. She looks so drained.’

‘Yes, she must be. I am relieved that she has you to turn to, Jenny. You have behaved with great restraint and yet so much sympathy. Many young ladies would have needed comforting themselves after what you saw.’

‘My feelings have been affected, but to give way at such a time when others had so much more right to be distressed would have caused unnecessary suffering. I did only what I considered proper, sir.’

‘No, no, you must call me Adam.’ He smiled at her. ‘You must know that your conduct has given me the greatest respect for your character. I think we were fortunate that you were here.’

Jenny flushed delicately. ‘You make too much of my part. Lucy is my friend and I thought only of her feelings—and your family.’

‘Yes, precisely. But I am keeping you when I am certain you must need some privacy and a place to rest. Goodnight, Jenny.’ He took her hand and touched it briefly to his lips.

‘Goodnight...Adam.’

She blushed prettily before turning away. Adam watched her mount the stairs. He noticed that she had a way of walking that was quite delightful. Her presence had lightened the load he might otherwise have found unbearable.

A swathe of grief rushed through him, but he fought it down ruthlessly. He would not give way to the arrows of grief that pierced him; anger should sustain him—anger and his admiration for a quiet young woman who had problems of her own to combat, but had unselfishly thought only of her friends.

* * *

Jenny closed the bedroom door. It had been a difficult evening and at times she’d felt close to giving way to a fit of weeping. However, she’d sensed that Lucy was on the verge of hysteria so she’d controlled her own nerves and done all she could to ease her friend’s terrible grief. And then Lady Dawlish, a kind but sensitive lady who seemed almost as overset by the tragedy as her daughter.

However, Mr Adam Miller’s kind words and the look in his eyes had lifted Jenny’s spirits. She was astonished at the change in his character, for at the ball in London he’d seemed proud and arrogant—but in times of stress and tragedy one discovered the truth about the people around one. She had gone from feeling wary when he offered to take her up in his phaeton, to being amused and now her feelings were far warmer than was sensible for a man she hardly knew.

Jenny had realised shortly after she was taken up in Mr Miller’s phaeton that he thought her in the position of an unpaid companion—perhaps some kind of poor relation. Her uncle’s antiquated carriage, the plainness of her gown, which her aunt had purchased in a spirit of generosity, but according to her own notions of economy, and something Jenny had said had made him think her if not penniless, then close to it.

Mr Miller—or Adam, as he’d invited her to call him—had taken pity on her because of her situation. What would he think if he knew that her father had left her comfortably situated? He might despise her, think her a liar or that she had deliberately deceived him. Yet there was no need for him to know. None of her friends knew the truth. Most must have assumed that her father had lost much of his money—why else would her uncle have disposed of his house, horses and carriages? Jenny thought it nonsensical for had she still been able she might have lived in her own home and paid a companion. Yet she was content to live with her friends. She liked pretty clothes and trinkets, but would not have bought an extensive wardrobe even had she been consulted. However, her aunt’s taste for very severe ensembles was not precisely what Jenny liked and, as soon as she received the allowance Mr Nodgrass had agreed to, she would indulge herself with some prettier gowns. For the moment grey or dark colours would be more suitable, because Lucy and her family would undoubtedly wear mourning for a time.

Taking the pins from her hair, Jenny let it fall on her shoulders. Dark and springy with red tones, it was apt to tangle and she had to attack it with her brush to make it settle into acceptable waves and curls. Her eyes were a soft grey, her mouth inclined to curve at the corners most of the time and her nose short with a sprinkling of freckles. She knew that she was considered attractive, though she thought her nose too short for beauty. Had Papa and Mama lived she would have been having her Season this year—or perhaps she might already have been married. Her father’s tragic death had led to her living in seclusion for months at her uncle’s house. The prospect of Lucy’s wedding had been enticing for she was due some gaiety and a relief from mourning, but that was no longer to be.

Her heart was too tender to feel resentment. For the moment all that mattered was to be of comfort to Lucy and her family. However, she could not help thinking that Adam Miller was one of the most attractive men she’d ever met. When he’d kissed her hand a tingle had gone down her spine and she’d been aware of an urgent desire to be taken into his arms and be kissed on the lips—and that thought was too disgraceful!

How could she think of such a thing at a time like this? Was she shameless?

Her thoughts were nonsensical. Besides, he had made his feelings about heiresses plain in London. Adam might need to marry one, but he did not like them. If he discovered that she was not the poor companion he thought her, he would probably imagine she’d lied on purpose to entrap him.

Shaking her head, Jenny hid her smile of amusement as the door opened and Lucy entered. She looked pale, but her tears had dried and when Jenny held out her hands she took them.

‘I have left him with his family,’ she said. A little sob escaped her. ‘Do you think he knows that I sat with him, told him I loved him? There is so much I wished to say and now it is too late.’

‘I am sure he knew you loved him...’

Lucy shook her head and turned away to unpin her hair. She slipped off her dress, but did not remove her petticoats. ‘I feel so guilty,’ she said. ‘Oh, Jenny. If only I could bring him back...if I could explain...’

‘Explain what, dearest?’

‘Nothing. I cannot speak of it now,’ Lucy said and dashed away her tears. ‘I must try to sleep if I can.’

‘We shall be quiet, but I am here if you want to talk.’

‘I need to talk, but I cannot yet,’ Lucy said, an oddly defensive expression in her eyes. ‘Perhaps in a few days—but you must not condemn me when I tell you and you must promise not to leave me. I do not think I could bear Mama’s smothering if you were not here.’

Jenny pulled back the sheets for her. ‘Come to bed, Lucy.’

Lucy smiled gratefully. ‘I think that perhaps I could sleep now.’

‘Yes, we shall both sleep if we can.’

Jenny lay listening to the sound of Lucy’s laboured breathing as she tried to smother her tears. Her body trembled as the grief poured out of her, but after a while she quietened and then fell asleep. Jenny was too thoughtful and uncertain to sleep herself for some time and the reason for her restlessness was a pair of dark eyes and a face that was almost too handsome.

* * *

‘Mark slipped away quietly with all his family about him,’ Adam said to the vicar when he called the next day. ‘I am certain Lord Ravenscar will want to talk to you about the arrangements, perhaps later this afternoon. He is resting for the moment.’

‘Yes, of course. I am entirely at his disposal. I shall return later.’

Adam nodded. Lord Ravenscar had already arranged for his son’s body to lie in state in the chapel for three days before the funeral.

‘The tenants and workers will want to pay their respects,’ he’d told Adam earlier. ‘He would have been their lord when I depart this earth and it is only fitting that they should have the chance to say goodbye.’

Adam had agreed. It also meant that he could now make a search of his cousin’s rooms, which he needed to do as soon as possible. Hallam had remained at the house through the night and he, Paul and Adam were to meet shortly to begin their search. Lucy and her mother were at that moment enclosed with Lord Ravenscar, but would be leaving for home later that morning. So if he were to make his search before escorting them, he must begin now.

After taking leave of the vicar, Adam went up to Mark’s room. Hallam and Paul were already there and had begun the search in Mark’s sitting room. Paul had the top drawer of the desk open and was looking through some papers he’d discovered.

‘I thought I’d take the dressing room,’ Hallam said. ‘Adam—would you do the bedchamber, please?’

‘Yes, of course.’

Adam walked into his cousin’s room. The bed had been stripped down to the mattress and left open, the maids having been told to leave it that way for the time being. All the bloodstained sheets and covers had been taken away to be burned. A shiver of ice ran down Adam’s spine as he approached the bedside cabinet. Pictures of his cousin lying in the bed made it feel wrong to be searching this room, which was why Paul and Hallam had decided against the task.

In normal circumstances the room would have been left for weeks or months before being touched, but they did not have that luxury. Painful as it was, it must be done now. Gritting his teeth, Adam pulled open the drawers of the chest at the right-hand side one by one. Mark’s trinkets had been thrown carelessly into them and there was an assortment of fobs, shirt pins, buttons, a silver penknife, a small pistol with a pearl handle, a pair of grape scissors and some gloves—a woman’s by the look of them. Also a scented handkerchief that smelled of roses, also a lady’s, almost certainly Lucy’s. There was besides a bundle of letters tied with pink ribbon.

Extracting the top one, Adam discovered that they were from a lady, but not Lucy—instead, her name was Maria. After dipping into the first, Adam formed the opinion that the lady had been Mark’s mistress for a time. She seemed to have accepted that their liaison must end when he married, but asked that they meet one last time—and she thanked him for a ruby bracelet, which he’d given her as a parting gift. He replaced the remaining letters unread.

In another drawer, Adam discovered a jeweller’s receipt for the ruby bracelet and also two more for a set of pearls and an emerald-and-diamond ring, also a gold wedding band. He searched all the drawers in the expectation of perhaps finding the jewels, but they were not to be found. He would have to ask if Paul knew anything of them and if they might be in Lord Ravenscar’s strongroom.

His search extended to a handsome mahogany tallboy, which contained Mark’s shirts, handkerchiefs, gloves, silk stockings and smalls. It was when he came to the very last drawer that he found a black velvet purse hidden under a pile of cravats and waistcoats. Drawing it out, he tipped the contents into his hand and gasped as he saw the diamond necklace. It lay sparkling on the palm of his hand, the stones pure white and large, an extremely expensive trinket—and not one that he’d seen an invoice for.

‘Found anything?’ Hallam’s voice asked from the doorway. Adam held up the necklace. ‘What is that? Good grief! That must have cost a fortune!’

‘Yes, I should imagine so. I found a receipt for some pearls and an emerald-and-diamond ring, but a bill for the diamonds was not amongst the receipts. This was in the tallboy, but no receipt.’

‘Mark bought pearls and a ring for Lucy,’ Hallam said. ‘I know because Ravenscar asked me if he should give them to her today. I thought it best to wait for a few weeks. He did not mention the diamonds so I have no idea...’

Paul walked in. ‘You’ve found something?’

‘This...’ Adam held it out for him to see. Paul took it, whistling as he saw the purity of the diamonds and their size.

‘This cost the earth. I wonder where he bought it. I saw Lucy’s wedding gift and I know where he bought the pearls and her ring—but he made no mention of diamonds. These would be worth a king’s ransom, I think. I’m certain Mark did not buy them for Lucy or he would have mentioned it.’

‘If he did buy them.’

‘You didn’t find a receipt for them?’ Adam shook his head.

Paul shook his head. ‘There was a load of receipts in a wooden coffer in the dressing room, but all for small things like gloves—oh, and a pair of pistols. I can’t imagine that Mark would have been careless over something like this. If he kept receipts for his shirts, why not keep one for a necklace like this?’

‘It should be here if he had one,’ Hallam said.

‘If?’ Adam frowned. ‘He must have bought it—mustn’t he?’

‘Mark wouldn’t steal, if that’s what you’re implying.’

‘Of course not—but what is the alternative?’

‘He might have won it in a card game,’ Paul suggested.

Adam nodded grimly. ‘Precisely. Now supposing the previous owner came to demand the return of his property?’

‘You think they might have quarrelled over it?’

‘Perhaps.’ Adam frowned. ‘It’s the only clue we have.’

‘I don’t see how it helps,’ Paul said.

‘A necklace like this will be recorded somewhere,’ Hallam said. ‘It must have come from a London jeweller. At least that is where I shall start to enquire as soon as the funeral is over.’

‘It must be put away in Father’s safe for the moment,’ Paul said, a wintry look in his eyes. ‘If that devil killed Mark to get this, he won’t leave it there. He may return and look again.’

‘Yes. I’ve searched all the furniture, but I haven’t been through Mark’s pockets yet.’ Adam glanced at his gold pocket watch. ‘I must take Lucy and Lady Dawlish home. I’ll finish in here later.’

‘Couldn’t face it myself,’ Paul said. ‘I’ll lock the necklace away—and then Father wants me to sort out the details of the service. He’s feeling under the weather.’

‘I ought to go home and make some arrangements,’ Hallam said. ‘If you wouldn’t mind finishing in here alone later, Adam?’

‘Of course not. Mark would understand why we have to do this. You shouldn’t feel awkward, either of you—but I know how it feels.’

The cousins left the suite of rooms together. Adam then locked them and pocketed the key. He was frowning as he went down to the hall, where Lucy and Lady Dawlish had paused to say farewell to their host.

‘It was so kind of you to come.’ Lord Ravenscar took Lady Dawlish’s gloved hand. ‘And you, Miss Dawlish. Words cannot express my feelings.’

‘Or mine, sir,’ Lucy said, looking pale and distressed. ‘Forgive me.’ She dashed a tear from her cheek.

‘Miss Hastings. You will come again on a happier day, please.’

‘Of course, sir.’ Jenny impulsively leaned up and kissed his cheek. ‘I am so sorry for your loss, sir.’

‘Thank you.’ He pressed her hand. ‘If you will excuse me now. Adam is to escort you both home.’

‘How kind,’ Lady Dawlish said, shaking her head as the elderly gentleman walked away. ‘It breaks my heart to see him so, Captain Miller.’

‘Yes, I fear he suffers more than any of us,’ Adam said. ‘His health is not all it should be. This is a severe blow. All his hopes were centred on Mark and Lucy for the future.’