Полная версия

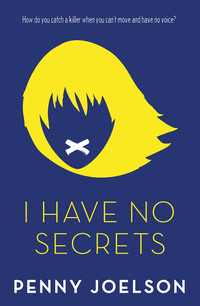

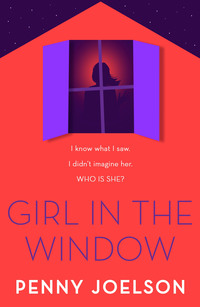

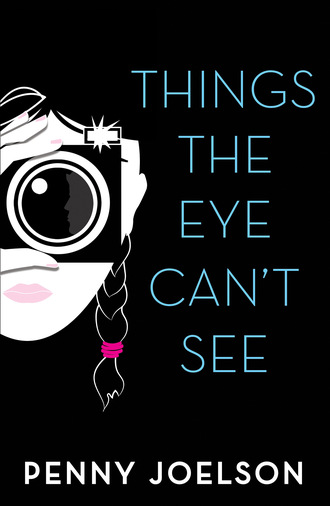

Things the Eye Can't See

First published in Great Britain in 2020

by Electric Monkey, an imprint of Egmont UK Limited

2 Minster Court, London EC3R 7BB

Text copyright © 2020 Penny Joelson

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

ISBN 978 1 4052 9491 1

eBook ISBN 978 1 4052 9514 7

www.egmont.co.uk

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher

Stay safe online. Any website addresses listed in this book are correct at the time of going to print. However, Egmont is not responsible for content hosted by third parties. Please be aware that online content can be subject to change and websites can contain content that is unsuitable for children. We advise that all children are supervised when using the internet.

To my nephews and niece,

Asher, Sammy and Layla

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

39

40

41

Acknowledgements

Back series promotional page

1

The voice startles me because it sounds like Charlie. I’m good at recognising voices, but it can’t be him, can it? Charlie used to be in my form group at school, but no one’s seen him for about six months. I’m down a quiet path – not far from my house. He’s calling my name.

I move my camera from my eye and stand upright. The poppy on the grassy verge, the one I was about to photograph with my macro lens, shape-shifts from perfect crimson petals around deep dark stamens to a slight fleck of red. I can only see clearly one or two centimetres in front of my eyes. My guide dog Samson shuffles beside me and stands as if expecting us to move on.

‘Wait, Samson,’ I say, pulling gently on his harness as I turn in the direction of the voice. Someone’s there, but he’s just a vague, dark blob.

‘Libby!’

He says it again – my name. His voice distinctive, gravelly, but sounding older than I remember. He’s coming nearer and the blur of him is familiar: the height, taller than me, light hair, the way he moves. It’s him – now I’m as sure as I can be. But I’m not sure if I want to talk to him – or if I ought to.

‘Charlie? Is it really you?’

I feel a pull as Samson turns too, his warm back nudging at my legs. ‘Sit, Samson,’ I tell him. ‘Sit.’ Samson sits obediently and I stroke his head.

‘Yeah . . .’ Charlie’s close now. He sounds nervous, awkward – and I’m not surprised.

‘Where’ve you been all this time?’ I demand. ‘You just dropped out of school. No one knew why.’

When he speaks his voice is low, bitter, emphatic. ‘Stuff . . . life . . . y’know?’ he says. ‘Things happen.’

‘I guess,’ I say.

‘And you,’ he says. ‘You got a dog now!’

‘Yeah – this is Samson,’ I tell him.

‘He’s lovely. You’re lovely, boy!’ he says to Samson. ‘I like dogs.’ He sounds sad now, wistful.

‘What happened, Charlie? Can’t you tell me?’

‘Na. But . . . I want to ask you something – a favour.’

My heart speeds up, wondering what he could possibly want. Perhaps I should have ignored him. I’ve always felt nervous around Charlie. He got excluded from school for fighting – more than once. He was sent to a referral unit for a while, for kids who can’t cope in school. Then he came back – only for about a month – and then he disappeared. No one knew where he’d gone. The truth is, no one cared all that much. School was calmer; there was far less tension without him.

‘What?’ I ask nervously.

‘D’you think you can take a message for me – give it to someone?’

‘Can’t you just DM them? Or text or something?’ I ask.

‘Nah. This is too sensitive. Top secret – and I can’t trust most people, but I trust you. I can, can’t I? Right?’

‘I guess . . . What’s this all about, Charlie?’

‘And you mustn’t tell anyone you’ve seen me,’ he goes on. ‘You get that?’

‘Are you serious? Why?’ I wish I could see his face, but I’d need to get too close to really see his eyes.

‘You gotta swear – this is dead serious,’ he says.

I can hear the desperation in the raspy tone of his voice. My mind slips back to one time at school when he was kind and helped me out. It was last year, before I got Samson. I was walking down the stairs with my cane and some impatient boy kicked it out of the way. I nearly fell – but Charlie was there and he caught me and gave the boy a right earful. I was a bit shaky and he was really sweet. I’d never seen that side of him before.

‘Please,’ he begs.

‘OK. I swear I won’t tell anyone.’ I say it – though I’m not sure I should, or if I mean it. ‘What’s the message?’

‘Here.’ He touches my arm, presses something into my hand. A small envelope. I hold it – at arm’s length initially, as if it might explode.

‘Put it away – in your pocket,’ he tells me.

I feel for my skirt pocket and slip the envelope in.

‘That’s right,’ he tells me. ‘Now give it to Kyle at school tomorrow, OK?’

‘Kyle?’ I repeat.

‘Yeah, don’t tell him you saw me or that I gave it you. Just give it to him quiet, like. You got it?’

Kyle’s the tallest boy in our year. Even I can generally pick him out.

‘OK,’ I tell him.

‘I knew I could trust you,’ he says. ‘I knew you’d help.’

‘Charlie . . .’ I start, but the blur of him is moving away and in an instant he’s gone from my vision.

I finger the straight edges of the envelope in my pocket. I’m anxious. I wish I’d said no – but part of me also feels chuffed that he’s chosen me for this task. He’s not seeing me as ‘the blind girl’ like most people do – but as someone who can help him, someone he can trust. It’s nice, in a weird sort of way.

I want to go home. ‘Forward,’ I tell Samson and he walks on eagerly, but my legs don’t seem to want to move and I stop. Samson stops too and nudges me in confusion as if to say, ‘Come on!’

I can hardly believe what just happened. My friend Madz is going to lose it when I tell her. But I shouldn’t tell her, should I? I promised Charlie. I wish I hadn’t promised that.

The flowers in the long grass are swaying, the dots of colour catching my eye as if beckoning me. I’m still holding my camera, so I lean over and take a few more close-ups, breathing deeply, calming myself until I feel ready to move.

‘OK, Samson,’ I tell him. ‘Forward. Yes – we’re going home.’

Samson’s up instantly and guiding me towards home. It’s a bright, warm day in early June, but something makes me shiver. I’m still thinking about Charlie. Why did he turn up here today? And what is in the note for Kyle?

2

When we get home, I ring the doorbell because I know Gran will be there and it’s easier than fiddling around with my key. My brother Joe should be home too.

‘Hi Libby!’ says Gran, opening the door. ‘You’re late. I was getting worried.’

‘Only a couple of minutes!’ I come in and take off Samson’s harness. ‘Good dog. Well done,’ I tell him, rubbing his head. Samson wags his tail against me and then pads off to the kitchen for a drink.

‘How was your day?’ says Gran, her voice softening. ‘D’you want a cup of tea?’

‘Ok, Gran – just a quick one,’ I tell her. ‘I’ve got tons of homework.’

I don’t mind a short natter with Gran, but sometimes it’s hard to get away. I’ve tried to tell Mum and Dad that I don’t need her here every day after school – and neither does Joe. I’m fifteen and he’s thirteen. We’re fine on our own. Mum works long hours, but Dad teaches at a primary school so he’s not back that late.

Mum gets it. She’s always wanted me to be as independent as possible. She said it was fine for Gran to stop coming – but then Dad got involved and he said he feels happier knowing Gran’s here. I was cross because I don’t want to be treated differently just because I’m visually impaired – but Dad explained that Gran is lonely and likes to feel useful. He said she’d be gutted if he told her we didn’t need her any more.

I can hear water gushing from the tap as Gran fills the kettle in the kitchen. I take the note from my skirt pocket and zip it into the front pocket of my school rucksack, before putting that on the bench by the front door where it lives. Everything has its place. I can’t be tripping over things all the time, or hunting them down because I can’t remember where I put them.

‘Here you go, love,’ says Gran, as I come into the kitchen. I reach for my usual chair and sit down at the kitchen table. I can hear Samson lapping water noisily from his bowl in the corner. Gran pushes a mug towards me and guides my hand to it.

‘Be careful, that’s hot,’ she says, as if I might not know. ‘Want a biscuit too? They’re shortbread.’

She holds out a plate and I take one. The best thing about Gran being here is her homemade shortbread.

‘Is Joe home?’ I ask, taking a bite and letting it melt gently in my mouth.

‘Yes – upstairs, like always,’ Gran sighs. ‘Hardly get a word out of him these days. But as long as he doesn’t bring any of those creatures down here . . .’

Joe, who goes to a different school and gets home before me, somehow manages to whisk himself off to his room without getting caught up with Gran. I don’t think Gran minds because it’s not easy having a conversation with Joe. He’s not exactly sociable. He used to be obsessed with computer games, but Mum and Dad got worried about it and decided to get him a pet as a distraction. Joe chose an iguana. Now Joe is reptile mad and has a room full of tanks and assorted creatures. He still hardly ever comes out.

‘Tell me all about your day,’ says Gran.

This is the bit I hate. Not much interesting happens, and even if it did, I’d not want to be telling Gran every detail. She always manages to say something that annoys me. Anyway, if I told her about Charlie and the note, she’d demand that I show her and she’d have no qualms about opening and reading it. She’d take over completely. It crosses my mind that maybe I should open it and read it myself with my magnifier. I’m tempted. I’d love to know what it says – but I promised. I can hear Charlie saying how he trusts me; I remember the desperation in his voice. Somehow, I don’t want to let him down.

‘English was good,’ I tell Gran. ‘We’re reading Pride and Prejudice. And I’ve got art tomorrow. I’m looking forward to getting on with my painting.’

Gran tuts. ‘Why you want to do art when you can barely see, I’ll never understand,’ she says. ‘Wouldn’t you rather do music? There are some amazing blind pianists, you know.’

This is Gran at her most irritating.

‘Gran!’ I protest. ‘I love art – and photography – and I’ve never wanted to play the piano! Mum says . . .’

‘Oh, please don’t start telling me what your mother says,’ Gran interrupts, sighing. ‘She and I will never agree. I hear she’s off to one of her conferences again next week? Where is it? Amsterdam, did your dad say?’

‘Yes.’

‘How long is it for this time?’ Gran’s disapproving tone is so obvious it makes me cross.

‘Five days, I think,’ I tell her. ‘But we’ll be fine. It’s important work that she’s doing. I’m proud of her, Gran. She’s trying to make a difference – to help to save this planet!’

Mum’s an engineer, developing environmentally friendly alternatives to plastic, and she gets asked to speak all over the world.

‘Yes, but you and Joe are important too,’ Gran insists. ‘She should get her priorities straight. He needs help, that brother of yours – spending all his time stuck in that room with those reptiles. It can’t be healthy. And you’re doing well, Libby, but you’re only just getting used to having a guide dog. Your mum should be helping you.’

I love Gran, but I’ve had enough of biting my tongue for one day. I stand up and push my chair back. ‘I’d better get on with my homework.’

‘Yes, I guess you had,’ says Gran, sighing. ‘But before you go – guess who I bumped into today?’

‘Who?’

‘Dominic!’ Gran exclaims. ‘Would you believe it – after all this time!’

Gran goes to a Book Group at U3A (University of the Third Age – classes for old people) on Thursdays and had started getting friendly with a guy called Dominic. We teased her because she seemed to bring his name into every conversation for a while, though she insisted they were ‘just good friends’. But then he stopped coming, and they turned out not to be such ‘good friends’ because they hadn’t even exchanged contact details so she had no way of keeping in touch. I wondered secretly whether he’d stopped because he got fed up with Gran, though I know that was a mean thought. He wasn’t young, and it also seemed possible that he might have died.

‘So where’s he been?’ I asked.

‘In hospital, poor soul. He had a heart attack, but he’s doing fine now. He’ll be back at the group next week, he says. And he asked if I’d like to meet him for coffee tomorrow!’

‘Ooh, Gran! Did you say yes?’

‘’Course I did!’ Gran chuckles. Then she adds, ‘I’d like to see you finding yourself a nice fella – someone who’ll look after you.’

‘Gran!’ I exclaim. ‘I don’t want or need some boy to look after me! And I don’t want a boyfriend right now, anyway.’

‘Sorry, sweetheart – have I put my foot in it again?’ Gran says. ‘Of course, there’s no rush, you’re right. I was sixteen when I met your granddad though,’ she adds. ‘And it might be harder for you – to find someone who’ll be prepared to . . .’

‘Gran!’ I exclaim again before she can finish that sentence.

I can hear Dad’s voice in my head saying, ‘I know she doesn’t always say the right things, but she means well, Libs. Her heart’s in the right place.’ But Gran really does go too far sometimes – and this is one of those times. I open my mouth to tell her how I feel, but then I close it again. Gran hurt my feelings, but hurting hers back won’t make it better.

‘I’m off upstairs,’ I tell her, and I go. Samson pads up the stairs behind me. I think he’s had enough of Gran too.

I sit at my desk and open my BrailleNote – it’s a laptop which converts my work from Braille to print and vice versa. So I can type Braille and print out a text version for the teacher to mark. I can also convert online handouts into Braille. I used to prefer to enlarge everything or use a magnifier, but now I have to do so much reading and writing, I’ve got faster at Braille and it’s much quicker and less strain on my eyes.

Samson curls up by my feet while I try to get on with my history homework – but my mind keeps slipping back to Charlie and the note. I wonder what it says, and I’m tempted once again to open it. But I’d have to go back downstairs to get it – and anyway, I promised. I wonder how I’m going to give it to Kyle without anyone else knowing. I wonder what kind of trouble Charlie’s in. I feel a nervous kind of excitement in the pit of my tummy. This isn’t the sort of thing that happens in my very ordinary life. Everything’s routine – at home and at school, going from lesson to lesson. But now I have a challenge – a task that takes me out of my normal zone.

Maybe I shouldn’t have stopped when Charlie called my name. Maybe I shouldn’t have taken the note. I could have said ‘no’. But I didn’t.

3

I’m walking to school, telling Samson, ‘Straight on,’ so he guides me along the road. Today I don’t feel like going down the path that cuts through to the station, where I was when Charlie gave me the note yesterday. The sun’s bright and I enjoy the warmth on my face. Cars zoom past one after the other, a constant hum. This, along with the smooth, hard pavement underfoot, feels reassuring right now, even though I usually prefer the birdsong of my usual route, with the occasional rattle of a train passing nearby, and the gravel, grass-edged path. There’s nothing to stop and photograph here.

I’ve put the note back in my skirt pocket, but it feels like it’s burning a hole. I’m still wondering what’s going on with Charlie, and also why and how Kyle is involved. He’s not exactly a friend of Charlie’s. I’ve never been aware of them hanging out. Kyle’s a bit off my radar. He doesn’t say much, so I don’t really notice him. The only thing I’ve noticed is his height. I’ve been paired with him a couple of times for projects and he has a nice voice, but he’s a bit of a loner and he seems to be absent from school more than most. He’s never been in trouble though – not even a detention for late homework as far I know.

My challenge is to somehow approach Kyle and give him the note without attracting attention. It isn’t going to be easy. I might think that he’s on his own, but there could be a bunch of people nearby who I don’t even know are there and who can see everything.

I always meet my best friend Madz at the school gate. I want to tell her. I wasn’t going to, but as I get closer to school I think maybe I will. I can trust Madz – and it would be a lot easier to do this with her help.

‘Hey Libs! Hey Samson!’ Madz is in her usual spot on the wall. She jumps down to greet me.

‘Hi Madz. You all right?’

‘Yeah. But last night was a disaster!’

‘Why?’ I ask.

‘I think I’ve made a mess of things with Ollie.’

‘Oh – what happened?’ I ask.

‘You know I was meeting him to see that film?’

I do know this. I was actually a bit peeved because I wanted to go to the film with Madz. And yes – I do enjoy the cinema. Once, when I had just started secondary school, a group of girls that I was hanging out with arranged to go to the cinema and didn’t even tell me, as they thought I’d be upset to be left out. When I told them I could have used headphones and audio-description (a voice describes the action through the headphones) and that I love going to the cinema, they were completely shocked. At least they didn’t leave me out again after that.

Madz and I go to the cinema quite often – or we did, until Ollie came on the scene three weeks ago. Now he’s all that Madz can talk about. I don’t want to be jealous of her having a boyfriend, but sometimes it’s difficult.

‘So what happened?’ I ask.

‘I only went to the wrong cinema, Libs! I went to the Vue and Ollie had booked for the Odeon!’

‘Oh no! What did you do?’

‘I felt such an idiot. I waited for ages – and then I called him, and I couldn’t believe it! I said I’d get the next bus, but he said it was crazy to miss the beginning and he’d get his mate to come instead. I’m gutted, Libby. I’ve got to find him now and make sure things are OK between us. I’m scared he thinks I’m stupid or that I wasn’t bothered enough to turn up. You don’t mind, do you?’

‘No, sure,’ I say. ‘He’ll be OK about it, won’t he?’

‘I hope so – I’ll see you at registration.’

‘Yes,’ I say, as we reach the doors.

‘Great.’ She touches my shoulder gently. And then she’s gone.

Someone shoves past me and I call out, ‘Hey, watch it!’

I hate the crowded corridors first thing in the morning. I direct Samson towards our form room and he leads me there, carefully weaving in and out of the crowds. I’m relieved when we reach the room and I’m in my chair, with Samson snuggled under the desk by my legs. I didn’t get to tell Madz about Charlie, and now I’m thinking about it, I’m glad I didn’t. I don’t need her help with this. I want to do it myself.

Five minutes later, Madz sneaks in beside me just as Miss Terri starts the register.

‘Well?’ I whisper.

‘He’s cool. I’m so relieved!’ she whispers back. ‘He’s asked me to watch him play cricket at lunch. Would you mind? Can you manage without me?’

‘You’re not my carer,’ I remind her. ‘I’ll be fine.’

I’m irritated that she thinks I can’t cope without her, but also that she didn’t ask me to join her. Not that I want to sit around at a cricket match.

Samson shuffles against my feet, as the implications of what she said start to filter through. I start to worry. Lunch in the dining hall is much easier with Madz. I don’t have to think too much because she always finds us a table, and makes sure I don’t put my lunch down too close to the edge, and that there’s an empty chair so I’m not sitting on someone’s bag where they’ve saved a seat.

I have other friends, but not close like Madz, and everyone has their lunch groups and routines. I’d feel awkward saying, ‘Can I sit with you at lunch?’ to Kaeya or Lilly. And then I’d have to ask them for that little bit of help too, but without them fussing over me. Madz does everything with no fuss. I forget she’s even doing it.

‘Are you OK? I feel really bad,’ Madz says.

‘It’s fine,’ I assure her. ‘You’ve got to have a life. I’m happy for you. I have to get used to doing stuff without you.’

I’m used to spending a lot of time with Madz – before school, lunchtimes, at least one night after school each week and one day at the weekend. I’ve never wanted her to feel that I’m relying on her. Our friendship hasn’t felt like that. Being with her is effortless and I don’t have to explain anything. Yet now she’s got a boyfriend and isn’t going to be around so much, I feel vulnerable and needy, and I don’t like it.

As well as the cinema, we go shopping together, take Samson to the park – all sorts of things. Apart from that, if I am out it’s with Mum or Dad and sometimes Joe too. All I actually do on my own, with Samson, is simple, familiar, routine journeys – the walk to and from school, sometimes the walk to the station to meet someone, the walk to Madz’s house and the walk to the shop at the end of our road.

We’d been talking about extending my reach – learning new routes to new places. It’s something I’d mentioned to Dad before, but he got all nervous and said we’d have to get Gina, my guide dog mobility instructor, to teach me and Samson the routes. Madz was going to help me, but now she won’t have time. I feel like my world is suddenly a little smaller.

‘I’ll still be around,’ says Madz, putting her hand on mine and squeezing. ‘We can still do things.’

I squeeze her hand back. ‘I’ll be fine. You’ll have to tell me every detail of how it’s going!’

‘Maybe not every detail!’ she giggles, as the bell rings for first lesson.