Полная версия

Blow by Blow: The Story of Isabella Blow

BLOW BY BLOW

THE STORY OF ISABELLA BLOW DETMAR BLOW WITH TOM SYKES

Blow by Blow is dedicated to Isabella’s memory

Contents

Chapter 1 The Call

Chapter 2 Johnny

Chapter 3 The Curse of the Delves Broughtons

Chapter 4 Evelyn

Chapter 5 Poor Relations

Chapter 6 Helen

Chapter 7 Heathfield

Chapter 8 Rona

Chapter 9 Evelyn’s Leg

Chapter 10 Eighteenth Birthday

Chapter 11 The Lovats

Chapter 12 Wolf

Chapter 13 Nicholas

Chapter 14 The Dispoasal of Doddington

Chapter 15 Texas

Chapter 16 Issie ♥ NY

Chapter 17 Anna

Chapter 18 André

Chapter 19 Divorce

Chapter 20 Tatler

Chapter 21 Independence

Chapter 22 Andy

Chapter 23 Inspiration

Chapter 24 Meeting Issie

Chapter 25 Falling in Love

Chapter 26 Courtship

Chapter 27 Engagement

Chapter 28 The Blows

Chapter 29 A Church Wedding

Chapter 30 The Restoration of Hilles

Chapter 31 Philip

Chapter 32 Duggie

Chapter 33 The Wedding

Chapter 34 Morocco

Chapter 35 London Babes

Chapter 36 The Death of Evelyn

Chapter 37 The Great Betrayal

Chapter 38 Alexander

Chapter 39 Elizabeth Street

Chapter 40 Sydney Street

Chapter 41 Exotic Fruits

Chapter 42 Highland Tragedy

Chapter 43 Alexander’s Betrayal

Chapter 44 Sophie

Chapter 45 Freelancing

Chapter 46 Theed Street

Chapter 47 Money Worries

Chapter 48 The Sunday Times

Chapter 49 Hotel du Cap

Chapter 50 Jeremy

Chapter 51 Modern Art

Chapter 52 Swarovski

Chapter 53 Russia

Chapter 54 ‘WOW’

Chapter 55 Dinner with Elton

Chapter 56 Economy, Issie-style

Chapter 57 Helen’s Last Visit

Chapter 58 New York, via Iceland

Chapter 59 Economy, Issie-style (II)

Chapter 60 Triumph, Disaster and Recovery

Chapter 61 The 3 Cs

Chapter 62 When Philip Met Isabella

Chapter 63 The Battle of Hilles

Chapter 64 Separation

Chapter 65 Reconcilliation

Chapter 66 Eaton Square

Chapter 67 Shock Treatment

Chapter 68 The First Attempt

Chapter 69 ‘I always hated Tesco’

Chapter 70 The Overpass

Chapter 71 Battles

Chapter 72 India

Chapter 73 Cancer

Chapter 74 St Joan

Chapter 75 Issie’s Farewell

Sources and Acknowledgements

Picture Credit

Index

Copyright

About the Publisher

CHAPTER ONE

The Call

I was at our flat in Eaton Square in London when I got the call. It was Issie’s devoted younger sister, Lavinia.

‘Detmar, I have just come home from shopping,’ Lavinia said frantically, ‘Issie has swallowed some poison. She says not to worry, as she has sicked most of it up. She seems ok. What shall I do?’

It was my wife Isabella’s seventh suicide attempt in fourteen months, and I felt a surge of anxious nausea as I tried to process Lavinia’s words.

Maybe this was it. Maybe this time she’ll succeed.

But poison? Where the hell had she found that? Was it weedkiller, like my father had used? And if it was, then how could she possibly still be alive? Issie was only 5′2½″ and weighed 7 stone. My father – 6′1″ and 18 stone – had drunk a bottle of paraquat in 1977 and it killed him in half an hour as the liquid burned out his insides. Amaury, my curly-haired 12-year-old brother, was there. He said Dadda never cried out, but that his fists were clenched in pain.

The only thing I knew was that if I was to be of any use to Issie at all, I had to remain calm and non-hysterical. ‘Take her to hospital,’ I told Lavinia. ‘I’ll be down as soon as possible.’

In a trance I called the milliner Philip Treacy, Issie’s best friend, who was meant to be picking me up later, because we had already planned to go down to Hilles, our house in the country, that weekend. I told him what had happened and he came round with his boyfriend Stefan and picked me up and we set off in his car for Gloucester Royal Hospital.

How could she still be alive? Maybe, I found myself hoping, as we crawled at an agonizingly slow pace through west London towards the M4, it wasn’t weedkiller. But I had a dreadful hunch that it was, because just a couple of months beforehand I had taken delivery of a bottle of paraquat at Hilles, ordered by Isabella.

I had been horrified, furious, and had asked Isabella, ‘What the hell is this? What are you doing?’ She had just remained silent.

I took it back to the farm shop in Gloucester where she had ordered it and told them, ‘The person who ordered this is trying to kill herself. Never send it again.’ The poor lady I spoke to was very upset.

I stared out of the car window in a daze as we hit the motorway and finally started picking up some speed. Surely the same farm shop wouldn’t have sold her paraquat? Could it be something she had found in the garage from my father’s stack of poison, left there since the seventies, which would be 30 years out of date?

When we finally arrived in Gloucester, we got lost. The Gloucester Royal Hospital is a big 1970s building with a huge chimney. I thought you couldn’t miss it, but because of the new housing developments around it the road was obscured.

After driving around the hospital for a while and getting nowhere I said, ‘Let’s get out and walk.’ Philip and I had to scramble over a wall to get into the hospital grounds.

We went to the hospital reception and asked for Isabella, but no one knew where she was. Eventually we found out she was in the Accident and Emergency ward, so we rushed there.

And that’s where we found her. My heart went out when I saw her. She was propped up in bed, looking sallow, and wearing a thin white hospital nightgown. She was on a drip, and looked and sounded weak.

‘Hi Det,’ she said.

CHAPTER TWO

Johnny

Why did my wife, Isabella Blow, the fashion icon, the legend, the toast of glossy magazines from London to New York, want to kill herself? To answer that question I would have to go back to the very beginning of Issie’s life, to her extraordinary childhood, to her relationship with her parents and to the great, central trauma of her life.

On 12 September 1964, her little brother Johnny, aged 2½ died in an accident in the garden when he fell into a body of water.

Issie was supposed to be looking after him. She was five years old.

‘Everything went wrong for the family after the death of that little boy,’ recalled Issie’s now 94-year-old godmother Lavinia Cholmondley (pronounced ‘Chumley’) when she was interviewed for this book at Cholmondley Castle in 2009.

Confusingly, there are conflicting versions of the events that led to Johnny’s death.

Issie had told me about it the first time we met, at a mutual friend’s wedding in 1988. She told me that Johnny was chasing a ball and followed it into the swimming pool, which had been built by her father to celebrate a good harvest that year. After inhaling water, he vomited up a half-digested baked bean – it was ‘nanny’s day off’, Issie said, so dinner had been from a tin – and choked on it. She said that she remembered the smell of the honeysuckle, and Johnny stretched out on the lawn. ‘My mother went upstairs to put her lipstick on,’ she said. ‘That explains my obsession with lipstick.’

A local press announcement about the birth of Isabella’s baby brother. In the photograph is Helen Broughton with her new son, John Evelyn, Isabella and Julia.

Issie knew this was a pivotal moment in her life, and, with typical disregard for the comfort zones of polite society, she would often describe the events of Johnny’s death – the swimming pool, the ball, the honeysuckle and, above all, the lipstick – to relative strangers. She would even talk about it to newspaper interviewers, prompting her mother, Helen, to retort that the story about the lipstick was, ‘An awful, unfounded lie.’

The version of Johnny’s death told by Issie’s stepmother, Rona, whom Evelyn married just under a decade after the accident (he and Helen were divorced in February 1974) is very different. Rona related this account at a meeting in the Sloane Club in London 2009:

Helen went inside to do something, not put on lipstick; that was a very cruel thing for Isabella to say. But she went in to do something, I don’t know what. And when she went inside, she said to Issie, ‘Keep an eye on Johnny,’ or ‘Watch out for Johnny’. So Isabella was playing with John, but then somebody who was coming down the lane stopped at the gate and called Issie over to the gate. Issie went over, and while she was over there – it happened. He choked on a piece of dry biscuit and suffocated, and then fell in a small pond, not a swimming pool. And then everybody blamed each other.

Had Issie felt responsible for what happened to Johnny?

‘No,’ replied Rona. ‘There wouldn’t have been anything she could have done anyway. She was five years old.’

But such rational reasoning doesn’t always stop people, especially small children, from feeling the emotion and burden of guilt, does it?

Rona conceded, ‘She felt blamed.’

By who?

‘She wasn’t blamed by her father,’ was all Rona, now 70, and cautious to the end, would say. ‘By someone else.’

Memory, of course, plays tricks us on all, but it is quite extraordinary how Isabella’s story and Rona’s story (presumably relayed via Evelyn) diverge. Isabella very deliberately painted her mother as self-centred and vain by constantly reiterating the detail about her not being present because she was applying lipstick. When she told me the story of Johnny’s death, it was always portrayed as a result of him falling into the swimming pool. Indeed, she added more and more detail to the story – how the pool had then been filled in by her grief-stricken father and another built to replace it. I was therefore amazed when, after we were married, Evelyn used to tell me that Issie swam like a fish as a child in the pool.

Never did Issie tell me about being called over to the gate, or about being asked to watch Johnny.

As her husband, I, of course, believe Issie’s account unquestioningly over that of her stepmother, which I never heard until researching this book. Rona was not there at the time and would have heard it secondhand, years and years after the event. And yet, when I recall how Issie recounted this horrific, defining event of her childhood, it is impossible not to notice the foundation stones on which Issie built both her personal myth and her dark aesthetic was being laid.

All the elements of the black fairy story that she told to and about herself are there: the indifferent, heartless mother, the father more interested in his drinks and his friends than his son, and the terrible irony of the fatal pool being built to celebrate the harvest.

Isabella remembered her mother blaming Evelyn, her father. Helen once told the story of Johnny’s death to a cousin of Isabella’s who herself had just been bereaved. Later, the cousin told Isabella and I that Helen blamed Evelyn – despite the fact that, even in her telling, the death of Johnny was clearly an accident.

When I was researching this book I discovered a contemporary report of the accident from The Times, dated Monday 14 September, 1964. It was headlined ‘Heir to Baronetcy found Drowned’:

John Evelyn Delves, aged two, heir of Sir Evelyn Delves Broughton and Lady Broughton, of Doddington Park, near Nantwich, Cheshire, was found drowned on Saturday in a shallow ornamental pool which was being built in the garden of his home. The boy was heir to a baronetcy dating back to 1660.

Mr Giles Tedstone, farm manager to Sir Evelyn, said today, ‘Sir Evelyn and Lady Broughton had been having tea with their children and friends on the lawn and the children wandered off afterwards to play. Lady Broughton missed young John a couple of minutes later and he was found dead in the pool.’

Artificial respiration was tried and Sir Evelyn then drove the boy to hospital but it was too late. The pool was only 18 inches deep and has now been filled in.

Lady Broughton is expecting another baby in a few months time. They have two daughters aged five and three.

The following day an inquest was held in Nantwich. Evelyn attended the inquest, and The Times also reported on it. At the inquest it was ruled that his son and heir had died of asphyxiation.

Dr John Heppleston, pathologist, said that a post-mortem showed that the death was due to a blockage of the windpipe by food, caused by vomiting which had followed immersion in water.

Questioned by Sir Evelyn, Dr Heppleston said it was possible that the boy slipped or fell into the water and the shock made him vomit. He could have been dead within part of a second.

Mr Leonard Culey, West Cheshire deputy Coroner, recording a verdict of accidental death, said by a chance in a million the shock of the water made the boy sick and he asphyxiated. It was a case that could not have been foreseen.

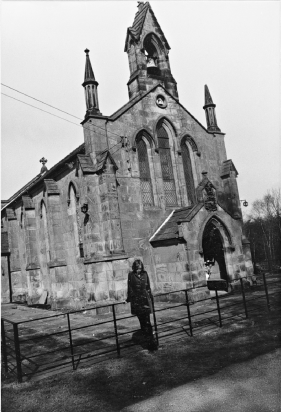

Isabella looking down at the grounds of St John’s Church, Doddington Park - the church where her brother John Evelyn is buried.

Whatever the exact sequence of events, there is no disputing that Johnny’s death, as well as traumatising Issie for life, destroyed the family utterly.

Evelyn’s reaction to Johnny’s death was extraordinary. Rather than trying for another son, he apparently became convinced that the death of John was a sure sign that the Delves Broughton line should come to an end with him.

The death of John, he appears to have decided, was to be the end of it all. It was a resolution from which he never wavered.

Johnny was buried in a small leather casket in St John’s Church in the grounds of Doddington Park, next to General Sir Delves Broughton, who built the church in 1837. Helen and Evelyn commissioned a stained-glass window in memory of their lost son. Isabella thought the window was ‘ugly but along the right tracks’. She respected their gesture of love.

CHAPTER THREE

The Curse of the Delves Broughtons

Tragedy ran deep in Issie’s family, and the stain on the Delves Broughton name went back to Issie’s grandfather, Jock. Sir Jock Delves Broughton had committed suicide, injecting himself with morphine in the Adelphi hotel in Liverpool after being accused of a notorious murder of a fellow aristocrat who was having an affair with his beautiful young second wife in Kenya in the 1940s (the subject of the book and film White Mischief). He was acquitted, but could not escape the smears of the press and his contemporaries, and many saw his suicide as a posthumous admission of guilt. Issie believed she had inherited her depression from Jock and was later to base one of her own unsuccessful suicide attempts closely around Jock’s successful one.

Isabella’s childhood was, by any normal standards, enormously privileged. It was, however, simultaneously defined by the economic anxiety of her father who was permanently terrified that what remained of the family fortune was about to slip through his fingers. As a boy, and later as a young man, Evelyn had watched helplessly while Jock spent, gambled and otherwise lost almost all his money.

Conversions into today’s money are notoriously unreliable, but by any reckoning the fortune Jock inherited in 1913 was staggering. In various family trusts, Issie’s grandfather was bequeathed not one but two stately homes (Broughton and Doddington Hall) and a collection of paintings, furniture and objets d’art accumulated over six centuries. There was also the not-so-small matter of 15,000 acres of prime farmland in three counties, a London residence, and a multitude of assorted stocks and shares. Isabella’s grandfather was the fortunate beneficiary of the aristocratic British tradition of concentrating all of the family wealth in the hands of the eldest son. The reasoning behind the right of primogeniture was – and is – to keep intact the great family homes and seats, the income from the land being used to ‘keep the title up’. This allows the title holder, if he so chose, to cut a dash in society, thereby adding to the lustre and importance of the family.

Jock and Vera at Royal Ascot in the 1930s.

Jock most certainly chose to do just that.

Doddington Hall was a grand house and Jock ran it on a correspondingly grand scale, retaining a large household staff. Oranges, melons and other exotic marvels issued forth from the laboriously tended (and heated) hothouses year round, and the Hall’s splendidly stocked cellar ensured the finest wines were served at dinner every night. He entertained lavishly, and his extravagance was legendary in society circles: a jazz band would frequently be engaged to play his weekend guests up on the 3½-hour train journey from Euston to Crewe.

The aristocracy were the celebrities of the day and the Broughtons enjoyed their fame. Vera – Issie’s grandmother whom she knew and adored – made particularly good copy for the era’s social diarists: amongst her many claims to fame, she held the record for the largest tuna ever caught in northern waters. She hooked it off Scarborough, in Yorkshire. Her fish weighed 317.5kg (700lb).

In Jock’s extravagance, some people discerned a desire to eclipse the events that overshadowed the beginning of his reign as the 11th baronet. For, just a year after he had inherited, in August 1914, the First World War broke out. Jock had supposedly been a professional soldier in the Irish Guards for over a decade, but was taken off the boat sailing for France to halt the invading German armies. The cause?

Sunstroke.

Jock sat out the war years at a desk in London, returning only occasionally to Doddington Hall. The Hall – which today is boarded up and languishes in a sorry state of disrepair – is a neo-classical fantasy built by Samuel Wyatt in 1770. The Hall was surrounded by a 500-acre park designed by ‘Capability’ Brown, with red and fallow deer and a 55-acre lake to the south ornamented with swans and birds. The lake boasted a banqueting hall on an island in the middle of it, which was subsequently demolished on the orders of a Broughton on account of his suffering too many hangovers. There were elegant stables designed by Wyatt, well stocked with fine horses to ride and take hunting, a tennis court and a croquet lawn.

The front of Doddington Hall. Country Life, 1950.

Doddington Hall’s circular salon with its huge chandelier. Isabella always loved the circular design - she had, at one time, a fl at in London with a circular room. Country Life, 1950.

The rear of Doddington Hall. Country Life, 1950.

Things began to go wrong for Jock when the money started to run out. Since the late nineteenth century, the British upper classes had been feeling an economic chill owing to the invention of refrigeration for container ships, which allowed imports of cheap food from abroad. In a speech in 1920 in the billiard room at Doddington to some of his angry and bemused tenants whose farms he was selling to raise £150,000, Jock explained to them that he believed that the landowning class was finished and he had no alternative but to sell their farms and look to the future.

He was far from alone in these views. The First World War had destroyed the political power of the European aristocracy and overthrown many monarchies. In Russia, Germany, Austro-Hungary and Turkey there had been revolutions deposing tsars, kings and sultans. Revolution was in the air, even in England.

During the 1920s and 1930s, Jock continually sold off land, investing heavily in commodities and what Isabella’s father Evelyn would later derisively refer to as a ‘tin pot gold mine’. In addition there were large, often unsuccessful horse-racing bets and other gambling debts. Broughton Hall was sold early on to a family that had made their money from reinforcing concrete with steel mesh. The economic depression of the 1930s only exacerbated Jock’s deteriorating financial situation, and, in desperation, towards the end of the decade, Jock started to make a series of fraudulent insurance claims. On one occasion he arranged for an out-of-work soldier to break into the Hall and steal some of the paintings whose insurance value he had recently increased. There were also claims on alleged thefts of jewellery, including one from the glove compartment of his car in the south of France. When Isabella was a child, a farm worker found a string of black pearls her grandfather claimed had been stolen wrapped around a branch in some farm woodland. Evelyn, his son and Issie’s father, handed them back to the insurance company.