Copyright

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers 2019

Copyright © C. J. Cooke 2019

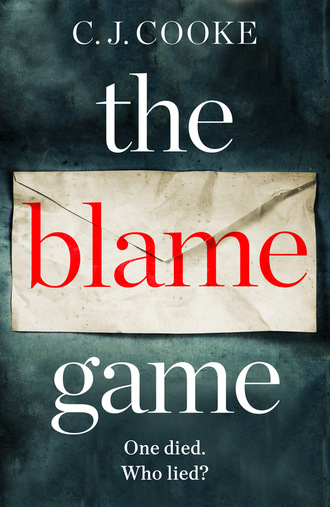

Jacket design by Dominic Forbes © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2019

Jacket photographs © Stephanie Frey / Arcangel Images (envelope); Shutterstock.com (extra texture).

C. J. Cooke asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008237561

Ebook Edition © March 2019 ISBN: 9780008237578

Version: 2019-01-21

Dedication

for Willow

Epigraph

But I know human nature, my friend, and I tell you that, suddenly confronted with the possibility of being tried for murder, the most innocent person will lose his head and do the most absurd things.

Agatha Christie, Murder on the Orient Express

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

Part One

1. Helen

2. Helen

3. Michael

4. Helen

5. Michael

6. Helen

7. Michael

8. Helen

9. Michael

10. Helen

11. Michael

12. Michael

13. Helen

14. Reuben

15. Helen

16. Helen

17. Helen

18. Michael

19. Helen

20. Helen

21. Michael

22. Helen

23. Reuben

Part Two

24. Helen

25. Reuben

26. Michael

27. Helen

28. Michael

29. Michael

30. Helen

31. Reuben

32. Michael

33. Helen

34. Helen

35. Helen

36. Helen

37. Michael

38. Helen

39. Michael

40. Michael

41. Helen

Part Three

42. Helen

43. Reuben

44. Helen

45. Helen

46. Helen

47. Reuben

48. Helen

49. Helen

50. Reuben

51. Michael

52. Helen

Part Four

53. Michael

54. Helen

Acknowledgements

A Q&A with C. J. Cooke

Keep Reading …

About the Author

Also by C. J. Cooke

About the Publisher

K. Haden

Haden, Morris & Laurence Law Practice

4 Martin Place

London, EN9 1AS

25th June 2006

Michael King

101 Oxford Lane

Cardiff

CF10 1FY

Sir,

We write again regarding the death of Luke Aucoin. The time to meet about this tragedy is long overdue. Please do not delay in writing to us at the above address to arrange a meeting.

Sincerely,

K. Haden

K. Haden

Haden, Morris & Laurence Law Practice

4 Martin Place

London, EN9 1AS

25th June 2010

Michael King

101 Oxford Lane

Cardiff

CF10 1FY

Sir,

We write again on behalf of our clients regarding the death of Luke Aucoin.

We request that you contact us immediately to avoid further consequences.

Sincerely,

K. Haden

28th January 2017

MURDERER

1

Helen

30th August 2017

I think I might be dead.

The scene in front of me looks like sea fret creeping over wasteland, closing in like a fist. A smell, too – sewage and sweat. There’s a flickering light, like someone bringing a torch towards the mist, and it grows so bright that I realise it’s my eyelids beginning to creak open, like two slabs of concrete breaking apart. Wake up! I shout in my head. Wake up!

Painful brightness. I can make out a ceiling with yellow stains and broken plasterboard, and a ceiling fan that spins limply. I try to lift my head. It takes enormous effort just to raise it an inch, as though an anvil is strapped to it. Where am I? My denim shorts and T-shirt are torn and caked in mud. I’m on a bed wearing one sandal. My other foot is twice its normal size, the blue nail polish that Saskia applied to my toes peeking through dried blood. I wiggle my toes, then my fingers.

I can feel my limbs. Good.

A nurse is busy replacing something at the foot of the bed. A urine drainage bag. A sharp tug at my side alerts me to the fact that the bag belongs to me.

‘Excuse me?’ I say. My voice is hoarse, no more than a croak.

The foreign chatter elsewhere in the room makes me think that the nurse might not speak English.

‘Sorry, but …? Excuse me? Can you tell me why I’m here?’

Even now, when I’ve no clue where I am or why, I’m apologising. Michael always said I apologise too much. I apologised all the way through both labours for screaming the place down.

A man arrives and consults with the nurse, both of them giving me worried looks as I try to sit up. He’s a doctor in plain clothes: a black polo shirt and jeans, a stethoscope and lanyard announcing his purpose. To my left is a window with a ripped insect net, and for some reason I want to go to it. I need to find something, or someone. ‘You must be careful,’ the doctor warns me in a thick Belizean accent. ‘Your head is very damaged.’

I reach a hand to my head and feel the padding of a dressing on my left temple. The skin around my left eye feels swollen and sore to the touch. I remember now. I remember what I was searching for.

‘Do you know where my children are?’ I ask him, the realisation that they’re nowhere to be seen making my heartbeat start to gallop.

The room lists like we’re rolling on high seas. The doctor insists that I lie down but I’m nauseous with fear. Where are Saskia and Reuben? Why aren’t they here?

‘This is you?’ The doctor holds a shape in front of me. My passport. I stare at it through tears. My face stares back blankly and my name is there. Helen Rachel Pengilly.

‘Yes. Look, I have two children, a son and daughter. Where are they?’

The doctor gives the nurse another deep look instead of answering me. Please don’t say they’re dead, I beg you. Don’t say it.

I begin to hyperventilate, my heart clanging like an alarm in my ears. And right as blackness reaches up to claim me, a sharp odour tugs me back into the room. Smelling salts. A cup of water materialises in front of me. The water’s got bits of dirt in it. Someone tells me to drink, and I do, because instinct tells me that perhaps if I obey they’ll tell me Saskia and Reuben are alive. Give me arsenic, a pint of oil. I’ll drink it. Just say they’re OK.

Another nurse brings a rickety wheelchair. She and the doctor help me off the bed and manoeuvre the drip-stand as I lower, my muscles trembling, on to the roasting hot seat-pad. Then we squeak through the ward towards a narrow, dimly lit corridor.

2

Helen

16th August 2017

It’s paradise here. Picture a narrow curve of white sand that arcs into the twinkling Caribbean. Six beach huts stood on stilts at a comfortable distance from one another along the strip, each with its own patch of ivory sand and acidic-blue ocean. No one around for about twenty miles, with the exception of the other two groups of people staying in the beach huts. A group of five from Mexico – I can’t tell if they’re family or just friends; their English is minimal and my Spanish is limited to ‘hello and ‘thanks’ – and at the very far end, the McAdam family from Alabama. Michael was suspicious of them at first when the husband asked a lot of questions about us, and I felt that familiar sting of panic, voices arguing in my head. ‘We’ll keep to ourselves,’ Michael announced cheerily as we made our way back to our hut, but I knew what he meant, and for one horrible afternoon I was wrenched back over two decades, into another century and another skin.

I make coffee and clear away the bowls left on the kitchen table. Saskia and Reuben are playing on the beach outside, their laughter drifting through the warm air. I pull two boxes of pills marked Cilest and Citalopram from my handbag and pop one of each out of the blister packs, knocking them back with a chug of water at the sink. Usually a glimpse of sunlight is enough to turn me into a lobster but my reflection shows I’ve caught my first actual tan in I don’t know how long, a deep bronze that knocks years off my face. Bright golden streaks have started to flash amongst my natural blonde, concealing the grey strands that have started to show. The sadness in my eyes, though – that’s always there.

We’ve been running for twenty-two years and I’m tired. I want to stop, lay down roots. It’s not in my make-up to live a peripatetic existence but we’ve had eight different addresses in Scotland, England, Wales, and even Northern Ireland. We tried to move to Australia but in the end it was too difficult to get visas. We don’t vote, don’t have social media accounts. Most of the time, we’re as normal as any other family. We’re content. Four years ago we made the huge decision not to rent any more and bought our first home, a pretty cottage in Northumberland. We have a dog and a guinea pig and Saskia and Reuben are thriving at their schools. But every now and then, I’m reminded of Luke. My first love. Especially at moments like this, when I’m happy and I remember I have no right to be.

Luke is dead because of me.

I’m putting on my sarong when Saskia comes screaming into the beach hut.

‘Mum, you have to come and see,’ she shouts, both hands splayed in front of her like a mime navigating invisible glass. When I don’t move she wraps her hands around my arm and yanks me with surprising force to my feet.

‘Starfish!’ she yells, skipping down the steps to the beach. ‘Careful,’ Michael says as we kneel on the sand to inspect them. A dozen orange starfish, bigger than Michael’s hand, studded with intricate patterns. He scoops one up, but instead of staying flat it begins to squirm.

Saskia bounces on the balls of her feet and points at something in the water. ‘Look! Right there!’ Reuben and I get to our feet and look out at the silky jade-green water. About twenty feet ahead is a pod of dolphins arcing through the waves, sunlight bouncing off their silvery backs. We all gasp. None of us have ever seen a dolphin in real life.

Saskia is weepy with excitement. ‘I have to go swim with them, Mum! Please, please, please!’

‘Here,’ Michael says, squatting in front of her. ‘Climb on.’

She jumps on his back and Michael quickly wades out to them while I hold my breath. Michael is capable, a strong swimmer. Dolphins are amazing creatures but the water is deep and there are endless dangers out there.

They’ll be fine, don’t spoil it.

I can’t watch. I busy myself by helping Reuben with his sand sculpture until Michael and Saskia emerge from the waves laughing and the dolphins have moved further down the bay.

We’ve been here two weeks, and by ‘here’ I mean the coast of Belize. Our original plan was to spend the school holidays travelling around Mexico. At Mexico City we joined a tour bus to the Yucatán via some jaw-dropping (and knee-wrecking) sights, such as the pyramids at the City of the Gods, where Reuben delighted in telling Saskia about mass human sacrifices. We saw the soaring white peak of the Popocatépetl volcano, the Temple of Inscriptions at Palenque, the pretty pastel-coloured streets of Campeche, and finally Cancún.

Reuben has adapted to the foreign setting more easily than I expected. The tour group was mostly older couples, so the bus was quiet and the air conditioning during long journeys helped to keep him comfortable. We had a problem at first with the lack of pizza – which is all he will eat – but we learned to improvise with tortillas laid flat and covered with salsa and cheese.

We went to Mexico for Reuben’s benefit. At least, that’s what we told everyone, including each other. Reuben did a stunning Year 9 project on the Mayans, involving a hand-crafted scale model Mayan temple and a 3D digital sketch that he projected on to black card surrounding the temple. We’d no idea he was capable of something like that and Michael said we should reward him. A trip to the real Chichén Itzá seemed the perfect way to do this, and as we’d not had a proper family holiday in a long time we figured a bit of a splurge was well overdue. But I also sensed that Michael was on edge, eager to run again. We’ve lived in Northumberland for four years now. Far longer than any other place.

When we arrived at Chichén Itzá Reuben sat in the tour bus for a long time, his face turned to the grey pyramid visible through the trees. Michael, Saskia and I all held our breaths, wondering whether he was going to start screaming or banging his head off the window.

‘Should I do the feet thing?’ Michael asked me nervously. The ‘feet thing’ is how we calm Reuben when he gets really worked up. I discovered it by accident when he was just a baby, and it grew out of the nights that I bathed him and then laid him on his mat to dry his little body. He’d lift his feet up towards my lips and I’d grab his ankles and blurt on the soles of his feet. It tickled him, made him laugh. As he got older and more sensitive to sound and chaos we tried everything to calm him. One night, when he’d worn himself out from screaming and lay down in bed on top of my legs, I ran my fingers up and down his shins. He started to calm down, then lifted his bare feet to my lips. I blurted them. He stopped crying altogether.

Ever since then, we do ‘the feet thing’ when he seems to be building up to a paroxysm – kissing a teenager’s smelly size tens and stroking his hairy shins somehow doesn’t have the same appeal as when he was a baby, but whatever works.

‘I think he’s OK,’ I told Michael, studying Reuben, reading the air around him. The trick is to approach him as you might approach a wild horse. No questions, no fuss – even when he strips naked in public places. We’d somehow convinced him to wear shorts in Mexico and he complied (we made sure to buy blue shorts), but he was still ignoring Michael at that point. I tried to tell myself that this was progress. After the thing between Michael and Josh’s dad, Reuben had gone ballistic, crying, screaming, smashing up his bedroom. I managed to get him to stop being so violent, but he withdrew and wouldn’t speak. Instead, he took to writing ‘Dad’ on his iPad and then vigorously crossing it out, signalling that Michael was dead to him.

At Chichén Itzá, though, I hoped that we could put everything behind us. Reuben looked from me to the pyramid – El Castillo – as though he couldn’t quite believe it was real; that he was here. I glanced at Michael, signalling that now was his chance to make amends. He turned around in the driver’s seat and grinned at Reuben.

‘We’re here, son. We’re actually at Chichén Itzá.’

Reuben kept his head turned away. Definitely not a sign that he wanted his feet to be stroked.

‘Do you want to climb to the top with me, Reuben?’ Michael asked gently.

He reached out to take Reuben’s hand, but Reuben sprang up from his seat and raced up the bus aisle, his long limbs moving in fast strides towards the clearing.

‘I’ll go,’ I said, and I reached down for my bag and followed after. Once I caught up with him I put my arm around his waist. We fell into step. He’s already six foot, even though he’s only fourteen. I wish he wasn’t so tall. It would make the sight of him clambering on to my knee for a cuddle or breaking down in tears when we’re out in public far less likely to draw stares.

‘You OK, sweetheart?’

He nodded but kept his head down. I handed him his iPad and followed at a comfortable distance while he raced off and began to film the site. We spent the day with the rest of the tour group exploring, giving Reuben hourly countdowns, as promised, so that he could anticipate leaving and manage his feelings of sadness a little better. Even so, when we got back into the bus at dusk I saw that his lip was trembling, and my heart broke for him.

We headed to the hotel at Cancún, and that’s where things started to go wrong. It was just too busy. Reuben’s noise-cancelling headphones usually keep him calm but the crowds and heat were overwhelming for him. Saskia and I were worn out by the searing temperatures and squabbling couples amongst our tour group too, and the guide seemed intent on traipsing around tourist-tat stalls instead of taking us to more ancient ruins. At one point Saskia lost her teddy, Jack-Jack, in a market and we had to spend an entire day trawling through souvenirs to find it. She’s had Jack-Jack since birth – a gift from my sister, Jeannie – and wouldn’t be consoled until we found him.

Luckily, we did, but we were all agreed – noise and crowds weren’t for us. So Michael went online and changed our booking to a small resort in Belize, within driving distance of a Mayan site even bigger than Chichén Itzá. Reuben was elated. We hired a car, broke free of the tour group and drove to this place.

I go back inside and pull laundry out of the washing machine, then take it out to the side garden to hang on the line. Michael comes into the garden, soaking wet from his swim. He’s in the best shape of his life, his arms broad and sculpted from deadlifts, his legs strong and muscular from cycling most nights to counter long days at the bookshop. His deep tan suits him, though I’m not sure about the beard he’s grown. He likes to say he’s ‘an auld git’ (he’s forty-one) but to me, he’s never looked better.

‘Where’s Saskia?’ I say, looking past him at the tide that has begun to creep up the beach, devouring Reuben’s sand sculpture.

He slicks his dark wet hair off his face. ‘Oh, I just left her to swim on her own.’

‘You what?’ I take a step forward and scan the part of the beach further to the left. In a moment, Sas comes into view, wrapping a strand of seaweed around her waist to make a mermaid tutu.

‘Honestly, Helen,’ Michael says, grinning. ‘You think I’d leave her to swim out in open water on her own?’

I slap his arm lightly for winding me up. ‘I wouldn’t put anything past you.’

‘Ouch,’ he says, flinching at my slap. ‘Oh, I found something in this shed here. Come have a look.’

He steps towards the plastic bunker that I’d assumed was the cistern and flings open the doors to reveal a storage cupboard chock-full of beach boards, wet suits, snorkels, windsurfing sails, inflatables, rockpool nets, and surfboards. He takes out a rolled up piece of thick cotton and inspects it.

‘Doesn’t look very waterproof. What do you think it’s for?’

We unravel it, each taking an end, until it’s clear that it’s a hammock. Michael nods at the palm trees behind me and suggests I tie one end to the fattest trunk while he fastens the other to a tree about eight foot in the opposite direction. Both trunks conveniently have metal hooks where other guests have secured the hammock.

‘Climb in,’ he says once we’ve set it up. I shake my head. I worry that I’m too heavy for it. I haven’t weighed myself in almost a year but last time I did – under protest – I was thirteen stone, an unfortunate side effect of long-term antidepressant use. I’m five foot nine so can carry it, but most of the weight has settled around my waist.

‘This is the life,’ Michael says, climbing into the hammock. Then, when he spots me tidying up the storage cupboard: ‘Helen. Get. In.’

The hammock stretches as I lie beside him, almost touching the ground, but it holds.

‘See?’ Michael says, slipping an arm under my neck and holding me close to his wet skin. For a moment there is nothing but the rustle of palm trees and Saskia’s singing on the back of the wind. I try to resist sitting up to check she’s OK and that Reuben is still on his iPad on the deck.

‘That’s better,’ Michael says, kissing the top of my head. He has his hands clasped around me and I can feel his chest rise and fall with breaths that grow gradually slower and deeper. How long has it been since we lay like this? It feels nice.

‘Maybe we should move out here,’ he says.

‘Definitely.’

‘Serious. You could home-school the kids.’

‘Mmmm, way to sell it to me. And what would you do? Build a book shack?’

‘Not a bad idea. I could be our designated hunter-gatherer. I reckon I’d make a good Caribbean Bear Grylls. I’ve got the beard for it, now.’

‘Bear Grylls doesn’t have a beard, idiot.’

‘Robinson Crusoe, then.’

I stroke the side of his foot with my toe. ‘I wish we could.’

‘Why can’t we?’

‘Blimey, if we’d the money, I’d move out here in a shot.’

‘Cheaper to live out here than England. We could make money by taking tourists out on boat trips.’

‘Stop winding me up,’ I say.

‘I’m not winding you up …’

‘Neither of us speak a word of Spanish, Michael.’

‘Buenos días. Adiós, per favor. See? Practically fluent.’

‘You wally.’

‘Anyway, they speak Kriol here.’

‘We don’t speak that either …’

‘Belize is a British colony. We probably wouldn’t even need a visa.’