Полная версия

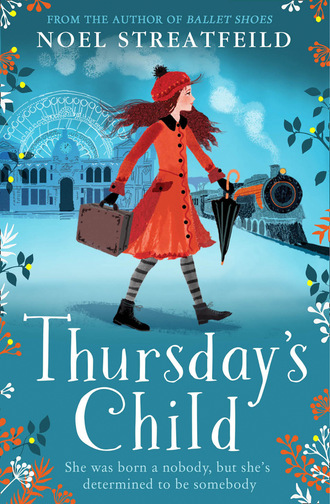

Thursday’s Child

Lavinia could see she was meant to curtsey and say ‘Thank you’, and she wished she could have, but she must arrange her days off.

‘Please, ma’am,’ she said, ‘what about my time off?’

Mrs Tanner frowned.

‘Her Ladyship does not give time off to you young girls, but sometimes, if there are no guests, you may go out together in the afternoon providing you do not leave the grounds.’

Lavinia swallowed nervously.

‘I quite understand, ma’am, but you see I have two little brothers at the orphanage. The younger is only six. So I can only take a place where I am permitted to visit them. I had thought perhaps every other Sunday.’

Mrs Tanner, as she told Lady Corkberry later, was so surprised she did not know how to answer.

‘A personable young woman, m’lady, very nicely spoken. I did not know what to answer because I understand she wants to keep an eye on the brothers. Still, it wasn’t for me to go against your rules so I said I would speak to you.’

Lady Corkberry was a good woman. Taking Jem into her house when he had pneumonia was not an isolated kindness. She expected to serve her fellow men when the opportunity offered; that, in her opinion, was what great positions and possessions were for. It was not her custom to meet her junior maids for she left their care to those immediately in charge of them, but this was an exceptional case.

‘Very well, Tanner, I will see the young woman in the morning room after breakfast tomorrow.’

Although it was her first day, Lavinia found that after she had unpacked and changed she was expected to work, but not before she had eaten. Midday dinner was over in the servants’ hall, but there was plenty of food about. Mrs Smedley, a large red-faced woman, pointed to a table by the window.

‘Sit there.’ She nodded at a dark-haired, anxious-looking girl. ‘This is Clara. You share her room. Give her some dinner, Clara.’

Lavinia remembered her instructions.

‘Thank you, ma’am.’ She sat while Clara put in front of her a huge plate of cold meat with a large potato in its jacket, a jar of pickles, a loaf of bread, at least a pound of butter and a great hunk of cheese.

‘Eat up, girl,’ said Mrs Smedley. ‘You’ll find you need to keep your strength up here.’

After the food she had eaten at the orphanage Lavinia needed no encouragement.

‘My goodness,’ she thought, ‘if all the meals are like this it will be a great temptation to take some leavings in my pocket for the boys.’

Mrs Smedley was right about Lavinia needing to keep her strength up for she did find herself very tired before she stumbled behind Clara up to their attic. There had been guests for dinner, and after running to and fro waiting on Mrs Smedley all the evening there had been a great mound of washing-up to do in the scullery. Then, after a supper taken standing, the girls set to at their housework. Blackleading the range, hearthstoning the kitchen and scullery floors and a long passage.

‘Terrible, isn’t it?’ Clara groaned. ‘And we’ve been one short until you came. Sometimes I’ve been that tired I haven’t known how to get up the stairs.’

But in spite of going to bed late and rising early, Lavinia looked, Lady Corkberry thought, remarkably fresh and pretty when Mrs Tanner brought her to her the next morning.

‘The young person Beresford, m’lady,’ Mrs Tanner said, giving a curtsey.

It was clear Mrs Tanner meant to stay, but Lady Corkberry did not permit that.

‘Thank you, Tanner. You may leave us. Your name is Lavinia Beresford?’ she asked.

Lavinia curtseyed.

‘Yes, m’lady.’

‘And you have two brothers in the orphanage?’

‘Yes, m’lady. Which is why I asked if I could have time off every other Sunday. I must see they are all right.’

Several things were puzzling Lady Corkberry.

‘You speak very nicely. Where were you at school?’

Pain showed in Lavinia’s face.

‘We did lessons at home with my mother.’

Lady Corkberry looked sympathetic.

‘She taught you well. A pretty speaking voice is a great advantage.’ She hesitated. ‘You say you must see your brothers are all right. Surely you know they are all right at the orphanage. It is highly spoken of.’

Lavinia did not know how to answer. She did not want Lady Corkberry descending on the place for Matron would, of course, guess who had talked, which might make things harder for the boys. So she hedged.

‘It’s not what they are used to. It will be better when they settle down.’

Lady Corkberry could feel Lavinia was hiding something, but she did not want to bully the child.

‘Very well,’ she said. ‘Every other Sunday.’ Then she smiled. ‘Perhaps one day in the summer I might have the little boys here for a treat. You would like that?’

A flush spread over Lavinia’s face.

‘Oh, I would, m’lady. It will be something for them to look forward to.’

‘Very well. Now go back to your work. I will see what can be arranged.’

Chapter Eight

A LETTER

Because she enjoyed the school and truly was getting to love both Miss Snelston and Polly Jenkin, Margaret, though she still meant to run away, had no immediate plans to do so. This was not only because of her promise to Lavinia and that she was growing fond of Peter and Horry, but also because of her Sunday underclothes. Whenever she thought of that lace-edged petticoat and those drawers she was so full of rage she felt she could not run away until in some way she had paid Matron back. Poor Susan, on the walk to school, would have been bored to exhaustion with the lace on Margaret’s Sunday underclothes only Margaret was always inventing new things she would like to do to Matron and Susan enjoyed hearing about those.

‘I would like a great enormous saucepan full of frying fat,’ Margaret would whisper through the hood of her cape, ‘and I’d push her in and fry her and fry her until she was dead,’ or, another day: ‘I thought of something in bed last night. I would shut her up in a cupboard with thousands and thousands of hungry rats so they would eat every bit of her.’

But Margaret did not only plan horrible ends for Matron, she collected information about her from the children, particularly those who had been in the orphanage since they were babies. As a result, she gradually built up a picture of the way Matron managed things. She learnt that in May each year Matron had a holiday. She went up north, it was said, to visit a brother, and that was when – so the story went – she sold any clothes belonging to new orphans which were worth selling.

‘She goes away with a great big box,’ a child called Chloe told Margaret, ‘and it weighs ever such a lot because Mr Toms has to carry it’ – Mr Toms was the Beadle – ‘and he swears ever so, but when she comes back it’s so light anyone could carry it.’

‘Clothes wouldn’t weigh all that lot,’ said Margaret.

‘It’s not only clothes,’ Chloe whispered, ‘it’s food. Our food. Last year we nearly starved before she went so she could take a huge joint of beef to her brother, and sausages and pounds of cheese and that.’

‘How do you know?’ Margaret asked.

‘Winifred, of course. They think because she works in the kitchen she’s one of them, but she never is, she’s still one of us.’

Margaret, turning over these scraps of information in her head, saw that they made a pattern. Somehow, before Matron went away in May, she must get back the clothes Hannah had made for her. And somehow she must get hold of her jersey and skirt before she ran away.

Meanwhile, Margaret did what she could to look after Peter and Horry, often getting punished for it. Punishments in the orphanage were tough. They ranged from being sent to bed without supper to beatings, but in between there were other terrors, such as being locked in a cupboard, being tied to a tree in the garden or being shamed by being sent to church on Sundays without a white fichu or, in the case of the boys, a white collar; this told the whole congregation a child was in disgrace. By suggestion, the children had learnt to look upon being disgraced in church as the worst punishment of all.

The very morning Lavinia left Margaret had secreted Peter’s two books under her cape and carried them to school. At school she had put them in his desk.

‘You can read all through playtime,’ she told him, ‘and other times, perhaps, if you ask Miss Snelston.’

Peter was delighted to see his books again, but he absolutely refused to keep both in his desk.

‘I must have a book in the orphanage, Margaret, it’s awful as it is, but with no book I think I’d die.’

‘But when could you read?’ Margaret asked him. ‘I know we are supposed to have free time every day, but mostly we don’t.’

‘It’s better for us boys, I think,’ Peter explained. ‘At least that’s what the boys say. They say Mr Toms doesn’t seem to mind if they don’t do much as long as Matron doesn’t know. They say he hates Matron.’

‘I bet he does. Who wouldn’t?’ Margaret agreed. ‘But where will you keep a book?’

‘I’ll find a place,’ said Peter confidently. ‘Out of doors somewhere, but of course safe from rain.’

Margaret looked in surprise at Peter. He was such a thin, pale little boy, most of his face seemed to be eyes. Yet he wasn’t at all weak, at least he wasn’t about things he cared about – like books. She had been thinking of him as a small boy, but now she remembered he was as old as she was.

‘Will you take a book home tonight?’

‘Of course,’ said Peter calmly. ‘Those horrible cloaks aren’t good for anything except hiding things in.’

But in spite of Peter’s confidence, Margaret felt responsible for him, so after tea she nipped out before tasks to see where the book was to be hidden. Peter had been ordered to act as donkey to the big lawnmower, tugging it along by ropes worn over each shoulder while another boy pushed. This suited Peter perfectly.

‘This is grand,’ he told Margaret. ‘Harry’ – he indicated the other boy – ‘says it’s all right if I read while I’m doing it, he’ll shout if I go crooked.’

That was the first time Margaret was caught and punished. She was slipping back into the orphanage when she ran slap into Miss Jones, who turned puce with rage.

‘Margaret Thursday! Where have you been? I distinctly heard Matron say you were to help in the kitchen.’

Margaret thought quickly. Whatever happened she must not mention Peter.

‘I thought I heard a cat crying.’

‘A cat!’ Miss Jones’s face turned even more puce. ‘We have no cats here, with a hundred orphans to feed and clothe we cannot afford to keep a cat.’

‘Thank goodness!’ thought Margaret. ‘Poor cat, it would starve in this place.’ Out loud she said: ‘May I go to the kitchen?’

‘At once,’ Miss Jones ordered, ‘but this will, of course, be reported to Matron and you will be punished.’

‘I think that’s mean when I was only trying to help a cat that wasn’t there,’ said Margaret, and dashed off to the kitchen.

Miss Jones, on her way to Matron’s office, muttered: ‘That is a very unpleasant child. There is something impertinent about her.’

Matron, when told about Margaret and the supposed cat, agreed with Miss Jones about the unpleasantness of Margaret.

‘One of these independent children,’ she agreed. ‘It will take time before she is moulded to our shape. Send her to me when she comes in from school tomorrow, she shall have ten strokes on each hand. That will teach her who is the ruler in this establishment.’

It was very difficult to help Horatio, but he so badly needed help Margaret did all that she could. There were two periods when he needed her most. One was morning washing time and the other was his free time when he came home from school. Two ex-orphans not suitable for farm work were employed on the boys’ side of the home to help keep discipline and to wash the little boys. They were loutish types in their late teens who enjoyed their small power and showed it by bullying and taking pleasure in being rough. It made Margaret mad to see poor Horry come into the dining room, his eyes red from soap, his cheeks shiny from tears. But Margaret, though seething with rage, kept her temper. She could do nothing for the time being for it was past imagining what the punishment would be if a girl was found in the boys’ dormitory.

‘Most likely I’d be beaten so hard I’d die,’ she thought, ‘and that wouldn’t help Horry.’

Then she had an idea. When on the train she had opened her wicker basket to give everybody toffee, she had told Lavinia she had three stamps. Lavinia already had a pretty shrewd idea what the orphanage was going to be like.

‘Hide them,’ she advised. ‘Stick them inside one of your boots, they won’t find them there.’ So far Margaret had not used a stamp for she did not want to write to Hannah or the rector with news which must depress them, for what could they do? And she certainly was not going to tell Hannah what had happened to her underclothes. But that meant she still had her three stamps and one of these she used to write to Lavinia. She took off the boot in which the stamps were stuck to the inside of the toe and took one out, then Miss Snelston gave her a piece of lined paper and an envelope and promised to post the letter.

Margaret had never received a letter. Although she did not know it, she would have been receiving letters regularly from the rector, had not the archdeacon warned him that it had been found that letters upset the orphans and so they were discouraged, so Margaret was very hazy how a letter should be worded. However, she did her best and at last she got over what she wanted to say. She wrote:

Margaret Thursday says when you come on Sunday she would be obliged if you could bring some sweets to bribe that beast Ben who washes Horatio very faithfully Margaret Thursday.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.