Полная версия

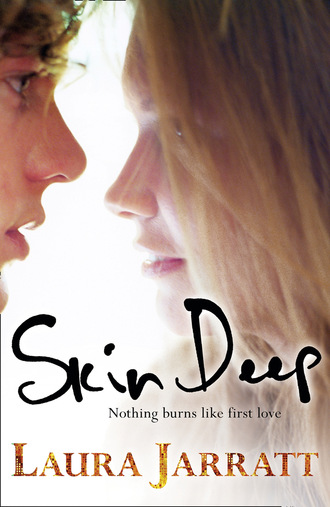

Skin Deep

‘Raggs! Raggs!’

‘Dead obedient, aren’t you?’ I said to him as he paid no attention to the voice and tried to hook his stumpy front legs over my shoulders so he could wash my hair too.

The girl appeared from out of the willow trees and stormed towards us. There was something odd about the way she walked – head down, hair over her face, shoulders tense. From what I could see, she had potential though – medium height, slim, sort of graceful even though she stomped along with her shoulders round her ears. Shiny hair the colour of a wheat field.

‘Hey, she’s hot,’ I whispered to the dog. ‘Stay here.’

She stopped about halfway, shouting ‘Raggs!’ again, not that it did any good. Her voice hitched on the name like she was close to crying and guilt pricked at me. Maybe she was a stupid up-herself bitch, but she was a girl on a deserted canal bank with a stranger . . . I didn’t like the idea I scared her.

‘Nice dog,’ I called out.

She didn’t come any closer.

‘He just wants to play,’ I shouted, but she still stayed close to the treeline. I gave up and pushed the dog down. ‘Go on, go back.’ He paid as much attention to me as he did to her, jumping straight back on to my legs. I nearly picked him up and took him over to her, but I reckoned I was less threatening crouched down. She started towards us again.

‘Raggs, come here!’

‘Who trained him?’ I said, grinning. ‘Cos you should ask for your money back.’

‘Raggs! Now.’

‘I think you’ll have to come and get him.’

‘I’m sorry he bothered you,’ she muttered when she got close enough for me to hear. I opened my mouth to say, ‘It’s all right, no worries,’ but the words choked in my throat when I saw the face behind the curtain of hair.

Jesus, her face . . .

The right side was chewed up by a wide scar running across her cheek, down her jaw and neck and disappearing into the collar of her T-shirt. Fuck, that was a mess. Not an old scar – still purple-red angry. But not brand new either as it was all healed up. The skin there wasn’t smooth like it should be, but rippled and puckered, especially on her neck.

What in hell had happened to her?

I didn’t see the rest of her face at first. The scar was all I could see, my eyes drawn to it like a driver rubbernecking at a crash scene.

She bent down and snatched the dog from me. That broke my trance and I caught a flash of her eyes springing tears before she turned away with the dog under her arm and hurried off.

I scrambled up. ‘Hey, no harm done. He was only playing . . .’

She all but ran down the path away from me.

No wonder she didn’t want to come over and get the dog. She must get that all the time – idiots staring at her with their gobs open, like Frankenstein’s monster had just lumbered into view.

You utter, utter dick! Why did you have to stare like that?’

Should I run after her and apologise? But what would I say . . . ‘Hey, I’m sorry I stared at your face’ . . . Hardly.

She disappeared into the trees.

I felt like shit. She only looked about fourteen and I’d made her cry. I should be ashamed of myself.

And I was.

I fished the bucket out of the canal. She’d gone and there was no way of making it right even if I had a clue where to start.

‘Ryan, I’ve got some tea for you here. Take a break,’ Mum called.

I went inside and Mum handed me tea in an enamel mug. I examined it. ‘What is it?’

‘Nettle.’ She beamed at me. ‘Very cleansing.’

Urgh! Gross. Reminded me of green piss. Not that I’d ever tasted green piss, but I reckoned nettle tea was how it would taste.

‘Did you finish the windows?’

‘No, I knocked the bucket over. I’ll go back out and do it.’

‘Drink your tea first. And you can tell me what you think of some of my new designs.’ Jewellery kit was spread across the table: stones, beads, silver wires and torcs and catches, leather cords.

I sat down on a floor cushion. No chance of chucking the tea in the canal then. Mum held up a silver torc with a jade stone carved into the shape of a dragon.

‘It’s great, Mum. You should make more of those. They’ll sell for sure.’

‘Good. It took me ages to get that right. Very delicate job, especially the tail. What’s wrong with your face?’

‘Nothing. Why?’

‘You keep rubbing it.’ She put her fingers on her right cheek. ‘Here.’

I flushed hot. ‘I do?’

She poked her tongue between her teeth in concentration as she threaded red beads on to a leather thong. ‘Mmm.’ Her hair was piled up in a scrunchie on top of her head. She looked like a pineapple.

‘Mum, if you get injured, like an accident, they can do plastic surgery to take the scars away, can’t they?’

‘Yes, but I don’t think they can make them disappear. Sometimes perhaps, but not always.’

‘What would give you really bad scars?’

‘I’ve no idea. I once saw a child with a terrible scar from pulling a hot pan off the cooker. Why?’

‘Just wondered. I’ll go and finish the windows.’

I filled the bucket again at the sink and managed to chuck the nettle tea away at the same time.

As I scrubbed the rest of the insect debris off the windows, I couldn’t get the puckered skin on the girl’s face out of my head, or the look in her eyes when she’d turned away. She’d have been pretty before that. Nothing incredible, just normal average pretty like a lot of girls are. Kind of cute in a quiet way. If I ran into her again, I wouldn’t stare. After all, I used to hate it when kids stared at me and Mum.

5 – Jenna

I towed Raggs down the lane away from the canal and we looped through the village so I didn’t have to go near that boat again. The stupid dog kept pausing to look anxiously at me and I tried to stop the tears rolling down my cheeks.

Even before the accident, that boy would be out of my league. I guessed he was a few years older than me and he was tall, around six foot, but he didn’t have that stretched-out look boys have when they’ve grown too fast. His shoulders were too broad for that and he had a whippy muscled thing going on that made me wonder if he worked out. The honey-coloured hair was streaked blonder on top and his nose had a touch of sunburn as if he spent a lot of time outside. He wasn’t boy-band pretty, but nobody would’ve thought him anything other than good-looking. Especially without a shirt.

If my feelings had gone away when I became ugly, life would be easier, but the wobble in my tummy when I saw a boy like that was still there. Even though he looked at me like I was a monster.

The tears fell faster, blurring the road ahead. ‘It’s all your fault, you useless dog! I told you to come back. I hate you!’

Raggs pulled out of the clump of brambles he was nosing in and ran towards me, his tail wagging.

‘Come on, you. We’re going home.’ Forget the weekend stretching ahead of me. I wanted to go home and crawl under my duvet and hide. Forever.

We passed Charlie in the garden where he was kicking a football around on the lawn. ‘Want to be in goal?’ he yelled as he dribbled the ball along on spindly ten-year-old legs.

‘No!’

He stopped and stared at me in surprise as I hurried into the house, leaving Raggs behind with him. ‘Jen, what’s up?’

I slammed the back door and ran upstairs.

In the bottom of my wardrobe, right at the back and wrapped in a towel, I’d hidden a make-up mirror, the only mirror I still had. I knelt down and unwrapped it with shaking hands. A wave of nausea rose up when I looked in it. It was as bad as ever. Like a horror film. The ugliest thing I’d seen outside the movies. No wonder that boy had looked disgusted. I bet he’d wanted to throw up at the sight of me. I did.

Better to have been Lindsay. Better to be dead than look like this.

The thing that lived inside me since the accident woke again. The thing that chewed me with grinding teeth. I wanted to hurl the mirror across the room. Scream. Break everything in sight. Rip the curtains down. Smash the window. Let the animal thing out.

But good girls don’t do that, don’t make a fuss, don’t upset parents. And I was a good girl so I curled up on the floor and sobbed silently instead.

When they took the bandages off in hospital for the first time, my dad had looked at me and cried. In fourteen years I’d never seen my dad cry, but he sat there and wept as if something inside him had broken. Mum tried to make him to stop, but he couldn’t so a nurse came and led him away gently. They weren’t sure they should give me the mirror after that. Mum and Dad were supposed to support me, but that wasn’t going quite to plan. I had to look in the end though. It couldn’t be put off forever. I told them that.

‘Now remember, you’ve still got a lot of healing left to do. This graft needs to take and it’ll be a while before the colour fades. The mask will reduce the scarring as long as you wear it properly. In a year’s time, it’ll look very different,’ the nurse said.

Mum’s hands trembled as the nurse raised the mirror to my face.

I looked in it and any shred of hope I had was butchered.

They gave me a jab to calm me down and the counsellor came later. Her face swam woozily in front of me. ‘Jenna, I need to check first that you understand what the doctors have told you about your burns.’

Yes, I’m not stupid. Third degree. Full thickness burns. They’ve been through all this with me when they harvested my skin for the grafts, and then again afterwards.

It means the burns are skin deep.

And beauty’s skin deep.

Mum knocked on the door. ‘Jenna, I’m going to the library. Do you want to come?’

No, I never wanted to leave the house again.

But that wouldn’t do. I’d promised I’d go out when the mask came off after those six long months. They’d been patient and hadn’t hassled me before that, but now they took every opportunity to get me out of the house. Refusing would lead to one of those conversations I didn’t have the strength for.

We got into Mum’s red Corsa and she drove carefully into town, making a fifteen-minute journey last twenty. She always expected me to be nervous in cars now, but I wasn’t. How much worse could it get?

Once we were in the library, she left me alone in the Fantasy section while she headed for the Crime and Thriller shelves. I found something I liked the look of and settled into a comfy chair to check it out. I hated taking a book home only to find it was unreadable so I always flicked through the first chapter before deciding.

I heard a voice at the desk counter next to me. ‘Is the craft shop closed?’

I looked up sharply. The boy from the canal . . . He was still in the shorts, but he had a white T-shirt on now.

‘Yes, the lady who runs it has gone for lunch,’ the librarian replied. ‘Can I help?’

‘My mum makes jewellery. I was going to ask if you’d be interested in a sample,’ he said, pulling a pouch out of his pocket. I wondered if I could slip away out of sight or if moving would make him notice me.

‘You’ll have to talk to Clare about that. She’ll be back in twenty minutes if you want to wait. Feel free to browse.’

Urgh! Now I had to move. I got up as stealthily as I could and ducked into an aisle. I sat down close to the shelf and let my hair fall over my face as I pretended to read.

Footsteps sounded on the cord carpet, the soft pad of trainers coming closer. And then . . .

‘Oh!’ He walked into me as he came round the corner and knocked the book from my hands. It skidded under the shelf.

‘Oh, sorry!’ He crouched down to fish the book out. ‘Didn’t see you there. Are you . . .’ He tailed off and I waited for the shudder.

He grinned at me.

What?

‘Hi again!’ He pulled my book out and handed it back to me. ‘I’m glad I’ve bumped into you . . . well, fallen over you! I wanted to say this morning, only you ran off . . . that . . . your dog . . . it’s fine. Dead friendly, isn’t he? I like dogs. Sorry if I came over as rude.’

I was too shocked to move away or speak. And . . . and he was looking me full in the face . . .

He had nice eyes – a sort of brown colour, warm and smiley. He’d looked at Raggs that way too.

He went on. ‘You surprised me, that’s all. The scar’ – he touched his face – ‘took me by surprise. I didn’t mean to be rude, honest.’

I gaped at him. Nobody ever, ever mentioned the scars. Their eyes slid away or they turned aside or they pretended they couldn’t see them at all. But nobody ever acknowledged them directly. Even my own family avoided talking about them in front of me, apart from those humiliating and painful times when Mum felt it was necessary for a serious chat about my progress. But in the way that he’d just done? So blunt? So matter-of-fact? No, nobody did that.

He scratched at his neck. His grin was sort of lopsided this time. ‘What I mean is, sorry if I screwed up.’

Screwed up? Oh yeah, you did that. For a few minutes in eight horrible months, I’d forgotten my face and enjoyed something as basic as taking the dog out. And then he’d made me feel like an ugly freak. Which I was, but I didn’t want to be reminded of it . . .

I blinked hard and opened my book, hoping he’d go away.

‘Good book? You read any of his before?’

I shrugged, unable to get words out, not knowing what to say if I could. Charlie aside, this was the first boy to talk to me since the accident. I avoided them at school and I’d have been shy of this one even before the accident. Close up, he was even cuter – the kind of boy girls would be drawn to like a magnet. My skin felt scratchy with nerves at having him so close, and having his eyes on my face.

‘I’ve read a couple. Not bad. He goes on a bit though.’ The boy chuckled. ‘So, do you come here often?’

Oh, I got it. That’s why he was talking to me. I was a joke. One big bloody joke. Talk to the freak and laugh behind her back about it later.

I scrambled up. ‘Fuck off!’

‘Hey, what’s wrong? I was –’

‘Fuck off!’

People turned to look at us and the shameful tears came again as they stared. As he stared.

I ran to find Mum.

She hurried towards me as I burst into the aisle. ‘Jenna, was that you shouting? What on earth is wrong?’

‘I want to go home! I want to go home now!’

‘Calm down. What’s happened?’

‘Now!’

From the corner of my eye, I could see the boy watching us, but he melted away when Mum stuffed her books on to a shelf and shepherded me to the door.

When we reached the car, she hesitated. ‘Are you sure you want to go home?’ she asked. ‘Only . . . well, Dad’s having one of his meetings.’

‘Oh, so that’s why you wanted me out of the house. I should’ve guessed.’

‘Darling, I know it upsets you and –’

‘I want to go home!’

She winced and put the car in reverse. I stared out of the window as we drove home in silence.

Dad’s meetings. His campaign group. The sorest of sore points. He hadn’t even had the courtesy to tell me about it. I’d found out when I came across a discarded newspaper. I came down one morning to find he’d rushed out and left the local rag open on the table by accident. I was folding it up when I saw the headline on the front page:

STRENTON MAN TAKES ACTION AGAINST THE MENACE OF DANGEROUS DRIVERS

I frowned and sat down to look at the article, my skin flushing and crawling the more I read:

Local businessman Clive Reed has taken his campaign to Parliament after enlisting the support of Whitmere M.P. Trevor Davies.

Following the car crash that led to the death of two teenagers and left his fourteen-year-old daughter horrifically disfigured, Clive Reed has been campaigning for action to be taken by county police to combat dangerous driving on our roads. The outcry caused when the eighteen-year-old driver of the car, Steven Carlisle, also of Strenton, was given a suspended sentence has made him even more determined to bring the issue to national attention. Carlisle was driving under the influence of alcohol and drugs, but walked free from court in June after the judge heard a range of character witnesses speak in his defence, including representatives from Whitmere Rugby Club. Carlisle received a lengthy driving ban, but with local opinion running high, Mr Reed’s pressure group has swelled in number.

David Morris, whose daughter was one of the two girls who died in the accident, has given the campaign his full support. ‘Clive has been amazing,’ he said. ‘After Charlotte was killed my wife and I were too distraught to organise something on this scale. Clive’s made people around here sit up and realise that we need to do something to keep our children safe.’

Mr Reed spoke to our reporter yesterday. ‘This verdict is a travesty of our justice system. The only fair result would have been a custodial sentence. We are now seeking a review of the handling of this case and we’re calling for tougher sentencing and a greater police presence on our roads.’ Mr Reed’s distress was clear as he added, ‘I would hate for any other parent to have to go through what we have all suffered.’

I was shaking when I stopped reading, and I was shaking again when Dad got home that evening and I confronted him. ‘When were you going to tell me?’ I asked as I threw the paper down on the table.

He sat down wearily. ‘When we thought you were ready.’

‘Horrifically disfigured – you let them print that in the newspaper. And down here’ – I prodded the paper – ‘it says a photo of me will be used in your leaflets. You’re going to put my photo in there. Without telling me. Without asking me.’ My voice rose to a scream. ‘What the hell gives you the right to do that?’

‘That was taken out of context,’ he protested. ‘It was only a suggestion from Charlotte’s dad. He thought it might help. Your mum said it wasn’t the right time to talk to you about it. We wouldn’t have done it without –’

‘Oh yes, like you told me about this whole campaign?’

‘Jenna, for God’s sake, we have to do something. That boy has ruined your life!’

The words were out there, though he looked like he could have bitten his tongue off for saying them. I got up and ran blindly to the door. He followed me up the stairs, putting his foot in my bedroom door as I tried to slam it.

‘Jenna, I didn’t mean that your life is over. Of course not, it’s all ahead of you. But look what he’s put you through, the pain, the operations. You could have died too!’

‘You didn’t even wait until the mask is off.’ I tore at the plastic mould on my face, but he grabbed my hands to stop me. ‘It’s me who has to wear this. Me!’

He hung on to my wrists. ‘Don’t. You’ll hurt yourself. It’ll be off soon. You’ll get back to normal then, see your friends.’

‘Oh yes, except my best friend is dead! It won’t be back to normal for her, will it? It won’t ever be normal.’ I hated Dad then. I’d heard him talk to Mum about how Lindz changed after her mum left and seen the frown crease his forehead when we went out together. He thought she was a bad influence. He couldn’t see her the way I did. How she glowed brighter than other people and that I wanted to sparkle like her.

‘But you’re alive, Jenna. Thank God, you’re alive.’

‘Yes, and I wish I wasn’t!’

Dad let me go and backed away. Mum came running upstairs and pushed him aside and he left me for her to deal with.

What he said stayed with me. There was no way out of this. I couldn’t go running to my parents and have them make it better like when I cut my knee playing with Charlie when we were little, or when I got stuck on my maths homework. This was never, ever going to go away. Like the man on the market stall, I’d be stared at. I’d be wrong all my life. No going back. No making me right.

Too soon we pulled into the drive. Mum had to park on the lawn because there were so many other cars there.

‘Why is he having it here?’ I muttered, wanting to know, but not wanting to speak to her either.

She hesitated before she answered. ‘Last time they met at the village hall, but the cars were vandalised. Paintwork keyed and the tyres let down.’

And I knew who’d have done that. We all knew.

‘They’ll be in the kitchen,’ Mum said. ‘Go in through the front door and straight upstairs if you don’t want to see them. I’ll bring you a hot chocolate.’

Charlie was doing trumpet practice in his room so I lay on my bed with my iPod turned up high to drown him out. Sometimes now I scared myself. Sometimes I couldn’t hold it in and go back to being Mum and Dad’s normal Jenna, even in the safety of my home. I wasn’t sure if any of that girl was still left. Perhaps the thing inside me had eaten her all away. Maybe I only acted at being her now.

Before the accident, I used to daydream about meeting a boy who didn’t want Lindsay or a Lindsay wannabe. He only wanted me. That was crazy thinking because Lindz was catnip for boys. She could get anyone she wanted. I’d watch her go into action, torn between admiration and jealousy, knowing I could never be like that. When she wanted the rich and unattainable Steven Carlisle, she’d even hooked him. But this dream boy would only be interested in me. We’d do regular things like go to the cinema, bowling with friends, hold hands, kiss eventually. Things I was ready for. Things Mum and Dad would be happy with. Things Lindz would laugh at as babyish.

And sometimes, after the accident, I used to dream it could still be possible. That someone would see past the scars and not care about them. Hopeless dreams. Stupid little girl dreams.

Dad sat on my bed and I jumped. With my headphones on I hadn’t heard him come in.

‘We’re having coffee and cakes. Come down and say hello.’

I turned the iPod off. ‘Why? So you can exhibit your freak to the crowd?’

His eyes registered his hurt and disappointment. ‘Where did that come from? Have some manners. Those people down there care about you. You’ve known most of them since you were a little girl. They’re doing this for you.’

‘If they care then they should leave me alone, like I want.’ I reached to turn my iPod on again, but he snatched it away.

‘Don’t be so selfish and rude. I want you down there in five minutes.’

So five minutes later, I went down to play the part of Daddy’s good, tragic little daughter. I smiled at the people while they smiled at my left ear. Mrs Crombie from the village shop cut me an enormous piece of chocolate cake and pressed me to eat it. Charlotte’s dad asked me heartily how school was going, which was brave of him, I guess, considering. Mrs Atkins from Belle Vue Cottage told me about her new kittens.

‘Does it make you sick to look at me?’ I wanted to ask. But Mum and Dad would never have forgiven me if I did, so I put the old Jenna on for them until I could escape back to my room.

Later, when they’d all left and the coast was clear, I crept down to the kitchen for a glass of milk. Mum and Dad were in the sitting room whispering to each other. I paused at the half-closed door to listen.

‘I’m worried, Tanya. She hardly comes out of her room. She won’t talk to people unless we make her. She never sees her friends. You said it would be different once she took the mask off.’

‘It’s only been a few weeks. She needs time to readjust. She’s gone back to school. That’s a start.’

‘But it seems as though she’s getting worse, not better. And what was all that about in the library today?’

‘I don’t know. She wouldn’t tell me.’

‘I know you’re worried too. I can see it in your face. She’s shutting herself off from everyone. I don’t want her getting like that poor bastard next door. He’s practically a hermit since Lindsay died.’

And I couldn’t stand to hear any more after that. I slunk back upstairs, the milk forgotten. Back to the safety of my room where I could lock the door on them all.