Полная версия

Stakeholder Capitalism

Deng wanted to change that, and in 1978, he visited Singapore. At the time, the island city-state was one of the four so-called Asian Tigers (Hong Kong, Taiwan, Singapore, and South Korea), economies that saw a rapid development in the 1960s and 1970s based on foreign direct investments (FDI), the shielding of key industries from foreign competition, and export-led growth. Having been inspired by the city-state's example, he pursued a new economic development model for China as well: the Reform and Opening-Up, starting in 1979. The kernel of the economic turnaround in this model lay in attracting FDI from some of China's neighbors, including Hong Kong, and allowing these investors to set up businesses in Special Economic Zones (SEZs) on various stretches along the populous Guangdong (Canton) coastline in Southern China. Shenzhen, north of the Sham Chun River, was one of them.

The SEZs were a sandbox for private business to operate in China. Elsewhere in the country, rules on private ownership, incorporation, and profits remained restricted for another number of years. China was a communist country after all. But in the SEZs, foreign investors could set up a business (provided it was aimed at exporting), own or at least lease property, and enjoy special legal and tax treatments.

The goal, researcher Liu Guohong of Shenzhen-based China Development Institute told us in 2019,115 was to give China a taste of a “market-oriented economy” (Deng would call it “socialism with Chinese characteristics,” and his successor Jiang Zemin talked of a “socialist market economy”). But there was virtually no money to develop any economic activity, so having SEZs close to Hong Kong—with its broad pool of money and manufacturing—was the next best option.

The bold plan worked. In 1982, Nanyang Commercial Bank, a Hong Kong–based financial institution started by a Chinese immigrant, set up a branch in Shenzhen, just a few miles north of Hong Kong. It was the first commercial bank in mainland China,116 and its arrival marked a watershed moment in the development of the country. The Hong Kong bank set up a cross-border loan to its Chinese affiliate. It allowed the Shenzhen branch to finance long-term leases of land and the opening of factories in Shenzhen.

The Shenzhen authorities also did their part. Previously, land in China was solely state-owned, meaning it could not be accessed by private investors. Now, Shenzhen allowed foreign investors to use land for commercial and industrial purposes. In 1987 the Shenzhen SEZ even organized a public land auction, the first in China since the foundation of the People's Republic in 1949.117

During the 1980s, Shenzhen became the kernel from which an entire economy grew. Following the example of Hong Kong and Singapore, Shenzhen at first specialized in low-cost, low-value manufacturing. With incomes starting at under a dollar a day, it wasn't hard to offer competitive salaries, with workers producing goods for export.

The Asian Tigers took notice and were among the first to shift their production. Taiwanese, Hong Kong, Singaporean, and Korean firms moved in, creating wholly foreign enterprises aimed at export or partly owned joint ventures with Chinese investors, which allowed them to sell products within China too.

As a result, people from all over China began flocking to the SEZs, drawn by the jobs and the allure of being part of something new and growing. From some 30,000 residents in the early 1980s, Shenzhen grew to become a fully-fledged Tier 1 city of more than ten million people, alongside Beijing, Shanghai, and Canton's capital to its northwest, Guangzhou. Gone were the days of Shenzhen as a “sleepy fishing village” next to some paddies of rice.

As the Special Economic Zones were a runaway success, the Chinese government created more of them, mostly along China's east coast. Cities such as Dalian, close to Korea and Japan, and Tianjin, the main port city serving Beijing (and both now home to the World Economic Forum's Summer Davos meetings) as well as Fuzhou, home to many Chinese emigrants to Singapore, were added in 1984. In 1990, Shanghai's Pudong district was added, and another few dozen SEZs followed.

The export model functioned as a catalyst. Hundreds of millions of people moved to the coastal SEZs, confident that better salaries in factories, construction firms, or services awaited them there. China's cities exploded, and its rural hinterland emptied. Annual economic growth rates reached peaks of 10 percent and more. China grew from a poor country with a GDP of $200 billion in 1980, to a lower-middle-income one, with a GDP six times that size ($1.2 trillion in 2000).

As China embarked on its Reform and Opening-Up economic policies, some inside and outside the country also hoped its political process would change, similar to what happened in the Soviet Union and its sphere of influence, including Poland, Hungary, Czechoslovakia, East Germany, and of course, Russia itself. But while this movement in Europe eventually led to the disintegration of the regime and the birth of new, democratic ones, the Chinese government maintained its central role in political and economic affairs. The 1990s became boom years for China, as many Western companies moved production there, boosting employment, pay, and consumption.

By 2001, China had grown so much and become such an export powerhouse that the time felt right to enter the World Trade Organization (WTO), which fueled yet another wave of export-led growth. Western companies, which had previously been wary or simply unaware of the possibility of manufacturing in China, now also followed suit. American, European, and Japanese companies were among the prime clients of Chinese and Taiwanese manufacturers or creating their own joint ventures.

But China's original star performer didn't stand still. As time went by, the profile of Shenzhen's industrial activities changed. Known for cheap electronics manufacturing and homegrown copycat firms at first, the city became the Silicon Valley of hardware and the home to the “maker movement of technology,” as Wired put it.118 Start-up entrepreneurs from all over China, and increasingly the world, started to meet and exchange ideas in Shenzhen, building new and innovative companies along the way.

Today, many foreign companies still have massive manufacturing bases in Shenzhen. The most famous facilities may be those of Foxconn, a Taiwanese electronics company that employs a few hundred thousand employees and produces the bulk of Apple's iPhones (or at least it did so until recently, when geopolitical concerns forced “a quiet and gradual production shift by Apple away from China,” including to a newly built Foxconn facility in India119). It is just one of many Taiwanese and Hong Kong companies that provided the backbone of Shenzhen's early industrial expansion and still have a major footprint there.

But Shenzhen may now be better known for its homegrown technology companies. Huawei, for example, is the single largest manufacturer of telecommunications equipment in the world, making hardware to power entire fifth generation (5G) mobile networks. It also produces smartphones that can be found all over the world (except the US), though the recent trade war between China and the US has put a break on its expansion.

Huawei's success was a long time coming. In 1983, its founder, Ren Zhenfei, was just one of many immigrants trying his luck as a worker in the blossoming Shenzhen electronics industry, after a career in the Chinese army. Four years later, he founded Huawei, a small firm doing contract work for a Hong Kong equipment dealer. The story of the company's rise in the following 30 years in many ways reflects that of China as a whole.

There are many more such examples of Shenzhen start-up success (years of founding in Shenzhen are shown in parentheses):

● ZTE (1985): Producer of a variety of telecom equipment, including phones.

● Ping An Insurance (1988): China's largest insurance company and a major player in artificial intelligence. It now has 200 million customers, almost 400,000 employees, and posted $160 billion in revenue.120

● BYD (1995): Short for “Build Your Dreams,” BYD is now the world's biggest manufacturer of electric vehicles (EVs), according to Bloomberg, “selling as much as 30,000 pure EVs or plug-in hybrids in China every month.”121

● Tencent (1998): A technology conglomerate that owns the popular Chinese social media app QQ, a large share in e-commerce website JD.com, and the developer of the popular game “League of Legends.” It was founded by a group of Shenzhen residents, including current CEO, Pony Ma. It is the world's largest gaming company and one of its biggest social media and e-commerce players.

Shenzhen long ago stopped being a cheap manufacturing base, but it is still the southern star for China's development, which has entered an entirely new phase. After an era in which it was the factory of the world, China has turned the page. It is the second-largest economy in the world now, and the magnetic pole for many Asian and other emerging markets’ economies.

In this phase, SEZs with their focus on export continue to play a significant part. But they are increasingly eclipsed by new types of pilot zones: those of science parks, start-up incubators, and innovation hubs. There, tech start-ups and innovators are incubating products for China's increasingly tech-savvy and wealthy consumers and businesses. Shenzhen again is a leader in this field, but other locations, including Beijing's Zhongguancun neighborhood in the Haidian district (where ByteDance, the creator of TikTok, was launched), Shanghai's Zhangjiang hi-tech zone, and others are also contenders.

The Price of Progress

If you cross the Sham Chen River today, you enter a concrete jungle, the sprawling metropolis that is Shenzhen. But on a hot day in summer, you will hardly see more people in the street than you might have in the sleepy fishing village that preceded it. In part because of global warming, summer temperatures are now often so high that it's impossible to walk in the city without breaking a sweat. Instead, people have moved underground. They get around through the air-conditioned halls of Link City, an underground commercial street, or they stay in the cooled offices of the city's many skyscrapers. At other times, Shenzhenites suffer from flash floods,122 another phenomenon that has gotten worse as climate change has intensified. The city has gotten wealthy, but all its wealth could not save it from the forces of nature.

China's rise represents an incredible milestone, but it shouldn't distract us from the even bigger picture. The global trends we outlined in Chapter 2 are as valid for Asia as they are for the Western world. The entire world has been on an unsustainable growth path, endangering the environment and the fate of future generations. Moreover, the economic growth that China, India, and others achieved in recent years was often shared just as unequally as in the West.

For China, the inequality challenge is equally present, but the greater problem may be the looming burden of its debt. Until the financial crisis in 2008, China's total debt-to-GDP ratio of 170 percent was in line with that of other emerging markets, as Martin Wolf of the Financial Times noted in a 2018 essay.123 But in the decade since then, it has risen explosively. In July 2019, it stood at 303 percent, according to an IIF estimate, and after the first few months of the COVID-19 crisis it ballooned to 317 percent.124

This is a dangerous trend because much of Chinese debt is owned by nonfinancial state-owned enterprises and local governments who may use debt to boost economic output in the short run. However, with marginal returns on public and private investments sharply decreasing in recent years, top-line economic growth is decelerating as a result, and the debt overhang is becoming increasingly concerning. Trade tensions, a decline in population growth, or other factors may trigger a further slowdown in growth. If that happens, a Chinese crisis may reverberate globally.

Finally, while China led the world in installing new wind and solar facilities in the past few years, and President Xi at the UN General Assembly in September 2020 announced it wanted to achieve carbon neutrality before 2060,125 there are still some major hurdles left to get there. First, in spite of the new Chinese ambitions, the building of new renewable energy facilities in the country slowed in 2019, a trend that continued into the new decade.126 Second, China saw its oil demand rebound quicker than elsewhere after the COVID crisis, with 90 percent of its pre-COVID demand recovered by early summer of 2020. It was a good sign for the global economic recovery but less good news for emissions, as China is the world's second-largest consumer of oil, behind the US. And third, Bloomberg reported,127 Asia's share in total global coal demand will expand from about 77 percent now to around 81 percent by 2030. China, which produces and burns about half of global coal, and Indonesia were the world's largest coal producers, and each also produced significantly more in 2019 than the previous year, BP indicated in its 2020 Statistical Review of World Energy.128

Emerging Markets in China's Slipstream

China wasn't the only economy to make enormous leaps forward in the past few decades. In its slipstream, countries from Latin America to Africa and from the Middle East to Southeast Asia also rose. China needed commodities, and many of its fellow emerging markets could provide them.

Indeed, while China is a giant in both geographical and demographical terms, it is more modest in its possession of the world's most important resources, with the exception perhaps of rare-earth minerals. As it grew, constructing new cities, operating factories, and expanding its infrastructure, it needed the help of others to supply it with the necessary inputs.

This was a blessing for other emerging markets, especially those in China's immediate vicinity (including Russia, Japan, South Korea and the ASEAN region, and Australia) and those who had struggled to attain high growth rates before (including many developing countries in Latin America and Africa).

China's rise, in fact, fueled a great emerging-markets bonanza. A glance at the World Bank's and UN's trade databases for 2018129 gives an insight into just how much China's rise contributed to that of other countries. China today is the world's second-largest importer of goods and services, to the tune of some $2 trillion. In reaching that size, it gave more than one economy a huge boost, buying loads of commodities every year.

In 2018,130 for example, it imported huge amounts of oil from Russia ($37 billion), Saudi Arabia ($30 billion), and Angola ($25 billion). For mining ores, besides Australia ($60 billion), it counted on Brazil ($19 billion) and Peru ($11 billion). Precious stones such as diamonds and gold were imported mostly through Switzerland, with South Africa a runner-up. China also bought copper from Chile ($10 billion) and Zambia ($4 billion), while various types of rubber came mostly from Thailand ($5 billion).

Those were just the raw materials. As China climbed up the value chain, it started to outsource some of its production, moving factories to the new low-cost economies of Vietnam, Indonesia, and Ethiopia, to name but a few. The technology it once needed to import through foreign joint ventures, China now created itself, allowing it to become an importer of the finished goods it had produced abroad and an exporter of them to consumers in other countries.

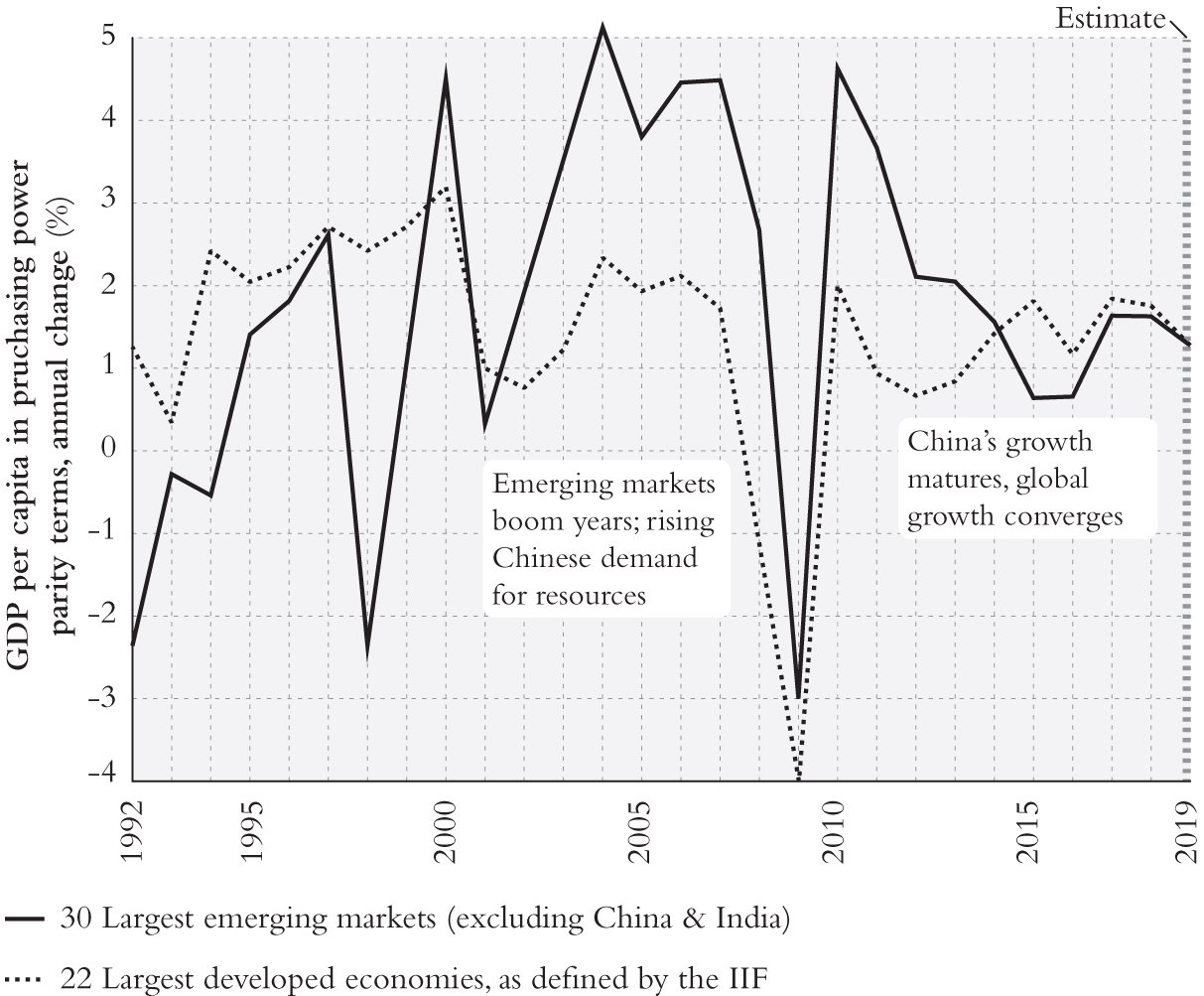

It is no surprise then, that just like China, many emerging markets experienced their own wonder years in the past two decades. The trend started slowly in the 1990s, when the world moved toward free trade, and it accelerated in the years following China's inauguration into the WTO in 2001. For over a decade, from 2002 to 2014, the Financial Times calculated,131 emerging markets consistently outperformed their developed world peers, not just in growth but in per capita GDP growth (Figure 3.1). The result was, as economist Richard Baldwin dubbed it, “the great convergence”:132 the incomes and GDP of poorer, emerging markets, moved closer to that of richer, developed markets.

Unfortunately, that trend in recent years has come to an end for most emerging markets, bar China and India. Since 2015, per capita GDP growth in the 30 largest emerging markets fell back below that of the 22 largest developed ones. The fact that China's growth in those years fell to under 7 percent is no exception. Its appetite for commodities is no longer insatiable, which put the brakes on their prices and trading volumes.

Figure 3.1 After a China-Fuelled Boom in the 2000s, Emerging Markets Growth Lags That of Developed Economies Again

Source: Redrawn from IMF, Real GDP growth, 2020.

That doesn't mean growth has petered out everywhere. Three regions in particular continue to perform well:

First there is the ASEAN economic community, home to some 650 million people, including from large and growing countries such as Indonesia (264 million people), the Philippines (107 million), Vietnam (95 million), Thailand (68 million), and Malaysia (53 million).133,134 Though an extremely diverse group of nations, both culturally and economically, the whole ASEAN community is set to return to the GDP growth path it had built up in the last few years before the COVID crisis hit, averaging some 5 percent per year.135 In the IMF's latest World Economic Outlook, dating from October 2020, the five largest ASEAN economies were in fact expected to experience a smaller than global average economic contraction in 2020 (–3.4 percent) and return to a 6.2 percent growth in 2021.136

One important reason for their sustained growth is that as a group, they are the closest to being the next factory of the world, a title China held before them. Wages in countries like Vietnam, Thailand, Indonesia, Myanmar, Laos, and Cambodia are often lower than in China, and their proximity to China and some of the world's most important sea lanes make for easy export to consumers around the world. Already, hundreds of multinationals from countries including China, the US, Europe, Korea, and Japan are producing there.

Another reason for their sustained economic success is that they're an agreeable neutral territory for the world's two major economic powers. Because of the ongoing trade tensions between the US and China, many companies are looking to shift production away from China to avoid tariffs. ASEAN, which has so far stayed out of the trade wars, has proven an attractive alternative. Vietnam has been a clear winner in this regard.137

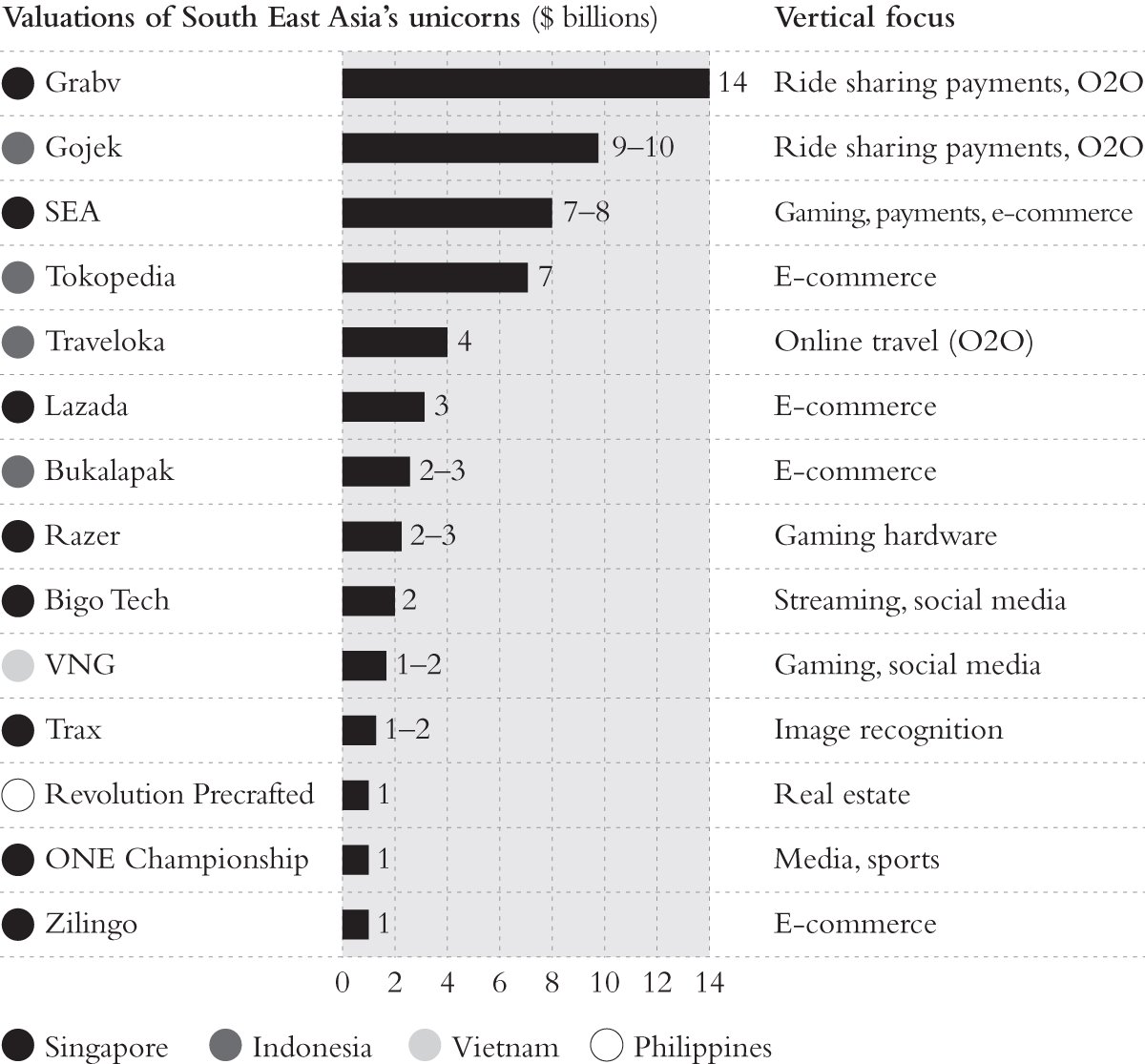

The third and final reason for its continued positive outlook is the mix of regional integration and technological innovation. ASEAN is arguably the most successful regional economic community after the European Union. Regional trade is rising and integration increasing. And it also created several homegrown tech unicorns, a term to describe privately held companies with a valuation of $1 billion or more. Singapore-based ride hailing app Grab is the most famous, but Indonesia's Go-Jek, Tokopedia, and Traveloka, several Singaporean start-ups, Vietnam's VNG, and the Philippines’ Revolution Precrafted also achieved that hallowed status (at least before the COVID crisis), according to consulting firm Bain & Company138 (Figure 3.2).

Growth in India

Another country that was experiencing strong growth prospects before the COVID crisis hit is India, though it was harder hit than most during the pandemic. For decades after its independence, the country struggled with the so-called Hindu rate of growth, a euphemistic way of saying “low growth.” Despite enthusiasm about its independence and young workforce, India's economy never achieved the runaway success of the Asian Tigers or China. The protectionist policies it pursued, alongside the red tape of the so-called Licence Raj system, which effectively created monopolies, precluded it from making such progress.

Figure 3.2 By 2019, Southeast Asia Had at Least 14 Tech “Unicorns”

Source: Redrawn from Bain & Company, November 2019.

India also remained largely unindustrialized, with hundreds of millions of people living on the countryside, earning only what they could get from small-scale farming. The resulting socioeconomic picture until well into the 1990s was one of a massive rural population living close to or under the poverty line and another large part of the population trying to come by in the country's mega-cities, which nevertheless offered less opportunities for advancement than those in Japan, the Asian Tigers, or China.

Starting the 1980s, however, some entrepreneurs started to gradually change the face of this rural, under-industrialized India. As the computer revolution took off, some entrepreneurial individuals, often hailing from the country’s Indian Institutes of Technology (IIT), managed to build some of the world’s most successful IT outsourcing firms, such as Infosys and Wipro. Leading industrialists also added to the burgeoning tech scene with the creation of offshoots such as Tata Consultancy Services (TCS) (founded already 1968) and Tech Mahindra.

A number of industrial companies also emerged, initially focusing on basic products in raw materials, chemicals, and textile but later expanding to modern technologies such as telecommunication and the Internet. The best-known and largest example is probably Reliance Industries, led by Mukesh Ambani. By diversifying and investing in large new projects centered on Fourth Industrial Revolution technologies, Reliance and other large Indian conglomerates are playing a substantial role in ushering in the digital era in India. Their scope is comparable to that of the large Chinese tech firms, as they offer everything from e-commerce to banking and from Internet to TV.

Before India got hit by COVID, the country was making structural efforts to do away with its checkered macroeconomic legacy. Under Prime Minister Modi, in office since 2014, the central government made substantial market reforms, including a unified tax on goods and services, allowing for foreign investment in a variety of industries, and running a more transparent auction of the telecom spectrum.139 GDP growth in years before 2020 hovered between 6 and 7 percent per year, putting it on par or even higher than that of China.

COVID, however, halted that ascent abruptly. India's economy was expected to contract by over 10 percent, putting it on par with Spain and Italy as the worst hit economies, the IMF said in late 2020.140 And that top-line economic decline hid an even more dramatic situation on the ground, as millions of the country's poorest city dwellers felt forced to return to rural home villages on foot when the country went in lockdown on March 24. With 10 million migrant workers returning home,141 it became one of the largest intra-country migrations of the 21st century so far. Many of them walked for weeks to their home provinces, in the hopes of being better off there during the crisis. But the long journey brought many additional problems, not in the least for their physical health and safety.

Yet there are also a few reasons to remain optimistic about India in the longer term. The country will soon have the largest working-age population in the world (25 years old on average), and its government has done away with some of the biggest impediments to growth. The Licence Raj, which effectively rationed supplies and limited competition for many goods before, was abolished, and more steps toward a unified internal market are underway.

Still, many of its 1.3 billion people are underprepared to join a modern workforce. One major reason for this is the literacy rate in India, which is still only 77.7 percent in 2020,142 caused in large part by a low schooling rate among girls. It does not need to be this way. In the US, Indian immigrants are already heading some of the largest tech firms in the world, leaders like Sundar Pichai at Google, Satya Nadella at Microsoft, and Shantanu Narayen at Adobe Systems. In recent years, tech unicorns such as Paytm and Flipkart were started in India.