Полная версия

Stakeholder Capitalism

Swabia's prominent companies surfed this wave of globalization, too. “China was at the top of ZF's agenda,” Siegfried Goll, then a prominent ZF manager, testified in the company's written history.22 “The development of our business relations began already in the 1980s, initially by means of license contracts. When I retired in 2006, we had no fewer than 20 production locations in China.” According to the company's own records, “The first joint venture was established in 1993,” and by 1998, “ZF's position in China was so firmly entrenched that the first-ever founding of a fully owned Chinese subsidiary was possible: ZF Drivetech Co. Ltd. in Suzhou.”

For some, though, this globalization was too much, too quickly. In 1997, several Asian emerging economies experienced a severe financial crisis, caused in large part by unchecked financial globalization, or the flow of hot money, international investor money that flows easily from one country to another, chasing returns, relaxed capital controls, and bond speculation. At the same time, in the West, an anti-globalization movement took hold, as multinational companies started to have more control over national economies.

Even Ravensburger didn't escape the backlash. In 1997, the company management announced that it wished to “introduce a ‘pact for the safeguarding of production sites,’ as a ‘preventive initiative for the maintenance of national and international competitiveness,’” the European Observatory of Working Life wrote in a later case study on the mater.23 The result was the so-called Ravensburger Pact, in which the company offered its employees job security in exchange for concessions.

Although the pact was accepted by most workers, it also led to a deterioration in employee-employer relations. The industry union argued it went against collective bargaining agreements for the sector and that it was unnecessary, as the company had good economic performance. In the end, the hotly contested pact made all parties reconsider their relationship to each other. The union, which had typically been weak in the family-owned enterprise, grew stronger, and management took on a more constructive approach to its Works Council going forward.

In Germany, similar societal and corporate stresses around economic growth, employment, and the integration of the former East German states ultimately led to a new social pact in the early 2000s, with new laws on co-determination, “mini jobs,” and unemployment benefits. But the new equilibrium was for some less beneficial than before, and even though Germany afterward returned to a period of high economic growth, the situation soon got more precarious for many other advanced economies.

A first warning sign came from the dot-com crash in late 2000 and early 2001, when America's technology stocks came crashing down. But the greater shock to US society and the international economic system came later in 2001. In September of that year, the US faced the greatest attack on its soil since the attack on Pearl Harbor in World War II: the 9/11 terrorist attacks. Buildings representing both the economic and the military hearts of America were hit: the Twin Towers in Manhattan and the Pentagon in Washington, DC.

I was in New York that day on a work visit to the UN, and like everyone there, I was devastated. Thousands of people died. The United States came to a standstill. As a sign of solidarity, the following January we organized our Annual Meeting of the World Economic Forum in New York—the first it was held outside Davos. After the dot-com crash and 9/11, the Western economies entered a recession. For a while, the path of economic growth through trade and technology advances hung in the balance.

But the seeds of yet another economic boost had already been planted. As exemplified by ZF's increased presence there, China, the world's largest country by population, had become one of the fastest-growing economies after 20 years of Reform and Opening-Up, and in 2001, it entered the World Trade Organization. What other countries had lost in economic momentum, China gained and surpassed. The country became the “factory of the world,” lifted hundreds of millions of its own citizens out of poverty, and at its peak became responsible for more than a third of global economic growth. In its path, commodity producers from Latin America to the Middle East and Africa benefitted as well, as did Western consumers.

Meanwhile, on the ruins of the dot-com crash, surviving and new technology firms started to lay the beginnings of a Fourth Industrial Revolution. Technologies such as the Internet of Things came to the forefront, and machine learning—now dubbed “artificial intelligence”—had a revival and rapidly gained traction. Trade and technology, in other words, were once more back as twin engines of global economic growth. By 2007, globalization and global GDP had reached new peaks. But it was globalization's last hurrah.

The Collapse of a System

From 2007 onward, the global economy started to change for the worse. The world's major economies saw their growth motors sputter. The US went first, with a housing and financial crisis turning into a Great Recession that lasted several quarters. Europe followed next, with a debt crisis that started in 2009 and lasted several years. Most other global economies were caught in the middle, with a global recession in 2009 and real economic growth that hovered around between 2 and 3 percent in the following decade. (Specifically, between a low of 2.5 percent in both 2011 and 2019 and a high of 3.3 percent in 2017, according to the World Bank.24)

Slow growth now seems the new normal, as the motor of all economic growth, productivity gains, is lacking. Many people in the West are stuck in low-paying, insecure jobs, with no outlook for progress. Moreover, the IMF had already noted well before the COVID crisis that the world had reached unsustainable debt levels.25 Anno 2020, public debt, which had previously reached a high in the 1970s crises, was again at or near record levels too in many countries. According to the IMF's 2020 fiscal monitor, public debt in advanced economies reached more than 120 percent of GDP in the wake of the COVID crisis, an increase of over 15 percent in a single year, and in emerging economies shot up to over 60 percent of GDP (from just over 50 percent in 2019).26

Finally, more and more people are questioning even how useful it is to pursue growth as an indicator of progress. According to the Global Footprint Network,27 1969 was the last time the global economy didn't “overspend” nature's resources for the planet. Fifty years on, our ecological footprint is greater than ever, as we use up more than 1.75 times the resources the world can replenish.

All these macroeconomic, social, and environmental trends are mirrored in the incremental effects of decisions taken by individuals, companies, and governments, both local and national. And it confronts those same societies, which have come so far from the era of wars, poverty, and destruction, with an unpleasant new reality: they grew rich but at the expense of inequality and unsustainability.

▪▪▪Swabia in the 21st century, is in many ways as wealthy as it has ever been, with high wages, low unemployment, and many leisurely activities. The beautiful city centers of Ravensburg and Friedrichshafen in no way resemble the sorry state they were in in 1945. Ravensburg still provides a welcome for refugees, but this time the wars are further afield. Even the city's puzzle game manufacturer has adapted to a world of global supply chains and jigsaws disrupted by digital gaming.

But the puzzle the people of this region, its drivetrain and jigsaw manufacturers, and other societal stakeholders here and in other parts of the world have to solve is not an easy one. It is a global one, with many complex and interdependent pieces. So before we attempt to solve it, we need to list those pieces. It is this assignment that we will take on in the next chapter. And to guide us, we will get the help of a famous economist.

2

Kuznets’ Curse : The Issues of the World Economy Today

There might have been no better person to piece together the puzzle of the world economy today than Simon Kuznets, a Russian-born28 American economist, who died in 1985.

It may seem odd at first that a man who passed away in the mid-1980s would be so relevant to today's global economic challenges, but I believe the issues we are facing today may not have become so problematic had we better heeded the lessons of this Nobel Prize–winning economist.

Indeed, Kuznets warned more than 80 years ago that gross domestic product (GDP) was a poor tool for economic policymaking. Ironically, he had helped pioneer the very concept of GDP a few years earlier and had a hand in its becoming the holy grail of economic development. He also warned that his own Kuznets curve, which showed that income inequality dropped as an economy developed, was based on “fragile data,”29 meaning data from a relatively brief period of the post-war Western economic miracle that took place in the 1950s. If the period of his study turned out to be an anomaly, the theory of this curve would be disproven. Kuznets also never approved of the curve's off-shoot, the so-called environmental Kuznets curve, which asserted countries would also see a drop in the environmental harm they produced as they reached a certain state of development.

Today we live with the consequences of not having been more rigorous in our analyses or having been too dogmatic in our beliefs. GDP growth has become an all-consuming goal, and at the same time, it has stalled. Our economies have never been so developed, yet inequality has rarely been worse. And instead of seeing a drop in environmental pollution, as one might have hoped, we are in the midst of a global environmental crisis.

That we are facing this myriad of economic crises may well be Kuznets’ curse. It is the ultimate “I told you so” of an oft misunderstood economist and forms the root of the feeling of betrayal people have toward their leaders. But before we get deeper into this curse, let's examine who exactly Simon Kuznets was and find out what people remembered him for.

The Original Kuznets’ Curse: GDP as Measure of Progress

Simon Smith Kuznets was born in Pinsk, a city in the Russian Empire in 1901, the son of Jewish parents.30 As he made his way through school, he showed a talent for mathematics and went on to study economics and statistics at the University of Kharkiv (now in Ukraine). But despite his promising academic results, he would not stay in the country of his birth after reaching adulthood. In 1922, Vladimir Lenin's Red Army won a years-long civil war in Russia. With the Soviet Union in the making, Kuznets, like thousands of others, emigrated to the United States. There, he first got a PhD in economics at Columbia University and then joined the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER), a well-respected economic think tank. It was here he built his illustrious career.

His timing was impeccable. In the decades after his arrival, the US grew to become the leading world economy. Kuznets was there to help the country make sense of that newly found position. He pioneered key concepts that dominate economic science and policymaking to this day such as national income (a forerunner to GDP) and annual economic growth and became himself one of the world's most prominent economists along the way.

The economic development curve of the United States in those years was a turbulent one. In the 1920s, the country was on an economic high; it came out of the First World War swinging. The US emerged as a political and economic power and put its foot next to that of an already enfeebled British Empire. Britain had dominated the world during the First Industrial Revolution, ruling a third of the world until 1914. America instead became a leader of the Second Industrial Revolution, which really took off after World War I. US manufacturers introduced goods such as the car and the radio to the country's huge domestic market, selling them to a public hungry for modern goods. Aided also by a spirit of free trade and capitalist principles, a positive spiral of investment, innovation, production, consumption, and trade ensued, and America became the world's wealthiest country in GDP per capita terms.

But the heady experience of the “Roaring Twenties” turned into the calamitous Great Depression. By 1929, the booming economy had spiraled out of control. Inequality was sky-high, with a handful of individuals, such as John D. Rockefeller, controlling colossal amounts of wealth and economic assets, while many workers had a much more precarious existence, still often depending on payday jobs and agricultural harvests. Moreover, an ever-rising stock market, not backed by any similar trend in the real economy, meant financial speculation was reaching a fever pitch. In late October 1929, a colossal collapse of the stock market occurred and set in motion a chain reaction all over the world. People defaulted on their obligations, credit markets dried up, unemployment skyrocketed, consumers stopped spending, protectionism mounted, and the world entered a crisis from which it would not recover until after the Second World War.

As US policymakers grappled with how to contain and end the crisis at home, they lacked the answer to a fundamental question: How bad is the situation, really? And how will we know if our policy answers will work? Economic metrics were scarce, and GDP, the measure we use today to value our economy, had not been invented.

Enter Simon Kuznets. An expert in statistics, mathematics, and economics, he developed a standard way of measuring the gross national income (GNI) or gross national product (GNP) of the United States. He was convinced this measure would give a better idea of just how much goods and services were produced by American-owned companies in a given year. A few years later, he also became the intellectual father of the closely linked GDP, presenting the slightly different concept in a 1937 report to US Congress.31 (GDP takes into account only the domestically produced goods and services, while GNI or GNP include income or products produced abroad by companies owned by a country's citizens.)

It was a stroke of genius. Over the remainder of the 1930s, other economists helped standardize and popularize this measure of economic output to such an extent, that by the time the Bretton Woods conference was held in 1944, GDP was confirmed as the main tool for measuring economies.32 The definition of GDP that was used then is still valid today: GDP is the sum of the value of all goods produced in a country, adjusted for the country's trade balance. There are various ways of measuring GDP, but the most common is probably the so-called expenditure approach. It calculates total gross domestic production as the sum of consumption that stems from it (adjusting for exports and imports):

Since then, GDP has been the metric you will find in World Bank and IMF reports on a country. When GDP is growing, it gives people and companies hope, and when it declines, governments pull out all the policy stops to reverse the trend. Although there were crises and setbacks, the story of the overall global economy was one of growth, so the notion that growth is good reigned supreme.

But there is a painful end to this story, and we could have foreseen it had we better listened to Simon Kuznets himself. In 1934, long before the Bretton Woods Agreement, Kuznets warned US Congress not to focus too narrowly on GNP/GDP: “The welfare of a nation can scarcely be inferred from a measure of national income,” he said.33 In this he was right. GDP tells us about consumption, but it does not tell us about well-being. It tells us about production but not pollution or the resource use. It tells us about government expenditure and private investments but not about the quality of life. Oxford economist Diane Coyle told us in an August 2019 interview34 that, in reality, GDP was “a war-time metric.” It tells you what your economy can produce when you're in war, but it does not tell you how you can make people happy when you're at peace.

Despite the warning, no one listened. Policymakers and central banks did everything they could to prop up GDP growth. Now, their efforts are exhausted. GDP does not grow like it used to, and well-being stopped increasing a long time ago. A feeling of permanent crisis has taken hold of societies, and perhaps with good reason. As Kuznets knew, we never should have made GDP growth the singular focus of policymaking. Alas, that is where we are. GDP growth is our key measurement and has permanently slowed.

Low GDP Growth

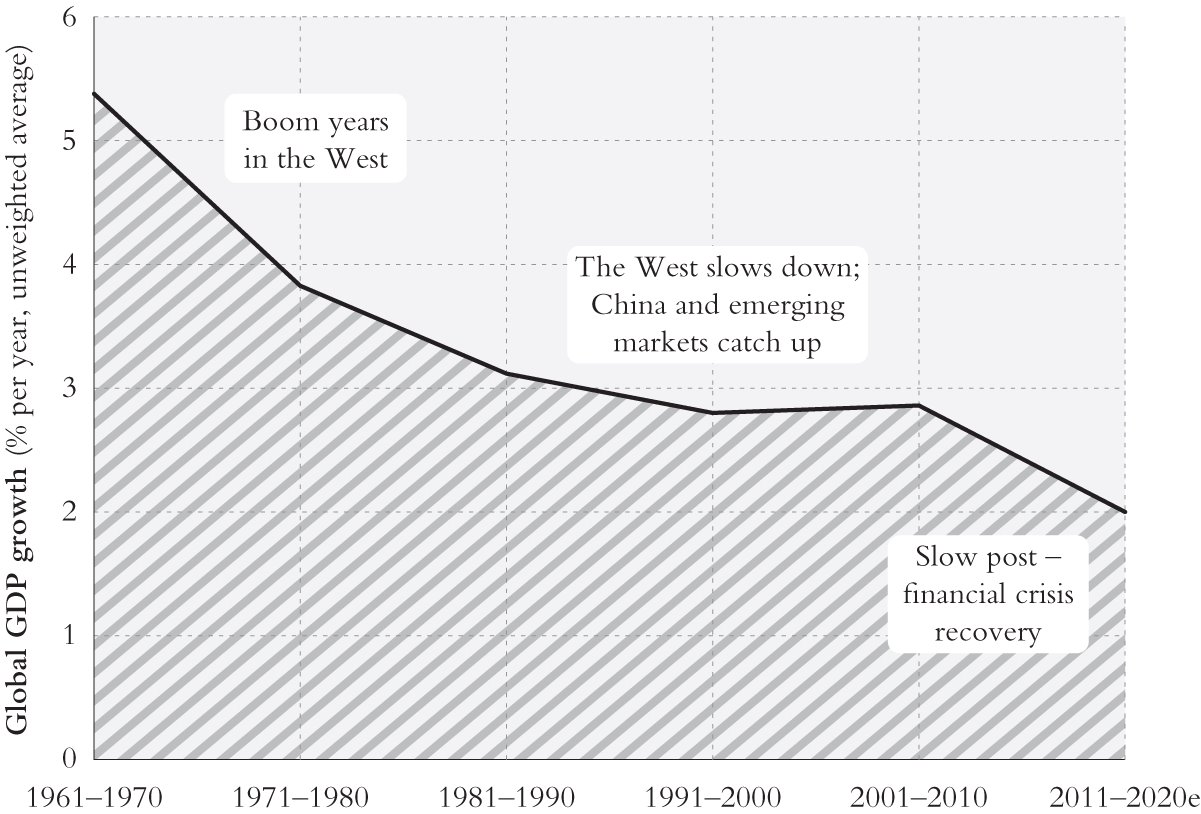

As we outlined in Chapter 1, the global economy in the last 75 years has known many periods of rapid expansion, as well as some significant recessions. But the global economic expansion that started in 2010 has been tepid. While global growth35 reached peaks of 6 percent and more per year until the early 1970s and still averaged more than 4 percent in the run up to 2008, it has since fallen back to levels of 3 percent or less36 (see Figure 2.1).

The number three matters, because it acted for a long time as a pass-or-fail bar of standard economic theory. Indeed, until about a decade ago, the Wall Street Journal pointed out, “Past IMF chief economists called global growth lower than either 3% or 2.5%—depending on who was the chief economist—a recession.”37 One explanation came from simple math: from the 1950s until the early 1990s, global demographic growth almost consistently lay at 1.5 percent growth per year or higher.38 A global growth rate that was only slightly over the rate of population growth meant large parts of the world population were in effect experiencing zero or negative economic growth. That type of economic environment is discouraging to both workers, companies, and policymakers because it indicates little opportunity for advancement.

Figure 2.1 World GDP Growth Has Been Trending Downward since the 1960s

Source: Redrawn from World Bank GDP growth (annual %), 1960–2019.

Perhaps in response to slowing economic growth, economists have since changed their definition of what constitutes a global recession. But it does not alter the fact we have seen meager global economic growth ever since. As a matter of fact, economic growth of less than 3 percent per year seems to be the new normal. Even before the COVID crisis, the IMF did not expect global GDP growth to return to above the 3 percent threshold for the next half decade,39,40,41 and that outlook has been negatively affected by the worst public health crisis in a century.

From the perspective of conventional economic wisdom, this could lead to systemic fault lines, as people got used to economic growth. There are two reasons for that.

First, global GDP growth is an aggregate measure, which hides several national and regional realities that are often less positive still. In Europe, Latin America, and Northern Africa, for example, real growth is edging closer to zero. For Central or Eastern European countries that still have economic catching up to do with their neighbors to the West or North, such low growth is discouraging. It may accelerate the brain drain, as motivated and educated people seek economic opportunities in higher-income countries, thereby exacerbating the problems of their home countries. The same is true in regions like the Middle East, Northern Africa, and Latin America, where many people still don't have a fully middle-class lifestyle and where jobs that offer financial security are lacking, as are social insurance and pensions.

Second, in regions where growth is higher than the average, like in Sub-Saharan Africa, even top-line growth of 3 percent or more per year isn't enough to allow for rapid per capita income growth, given their equally high rate of population growth. Low- and lower-middle-income countries that have posted relatively high growth levels in recent years include Kenya, Ethiopia, Nigeria, and Ghana.42 But even if they were to grow consistently at 5 percent per year for the foreseeable future, it could take an entire generation (15–20 years) for their people's incomes to double. (And that is assuming that most of the fruits of economic growth are shared widely, which often is not the case.)

Rapid progress and shared economic growth, like that seen in China in the early 21st century, require real growth rates of 6 to 8 percent in the least developed economies. Lacking this kind of super boost, the great convergence of economic standards of living between North and South, as predicted by some economists, will materialize very slowly, if at all. As Robin Brooks, chief economist at the Institute of International Finance (IIF) told James Wheatley of the Financial Times in 2019: “More and more, there is a discussion that the growth story for emerging markets is just over. There is no growth premium to be had any more.”43

Looking beyond GDP does not provide more promising prospects. Other economic metrics, notably debt and productivity, are also pointing in the wrong direction.

Rising Debt

Consider first rising debt. Global debt—including public, corporate, and household debt—by mid-2020 stood at some $258 trillion globally, according to the Institute of International Finance,44 or more than three times global GDP. That number is hard to grasp, because it is so big and because it includes all sorts of debt, going from public debt sold through government bonds to mortgages from private consumers.

But it has been rising fast in recent years, and that certainly is “alarming,” as Geoffrey Okamoto of the IMF said in October 2020. Not since World War II were debt levels in advanced economies so high, the Wall Street Journal calculated,45 and unlike in the post-war period, these countries “no longer benefit from rapid economic growth” as a means to decrease their burden in the future.

The COVID pandemic, of course, brought an exceptional acceleration of the debt load in countries around the world, and especially for governments. According to the IMF, by mid-2021, in the span of a mere 18 months, “median debt is expected to be up by 17 percent in advanced economies, 12 percent in emerging economies, and 8 percent in low-income countries”46 compared to pre-pandemic levels.

But even without the pandemic, debt had been creeping up in the past three decades. As one example: in advanced economies, public debt rose from about 55 percent in 1991, to over 70 percent in 2001, and more than 100 percent in 2011. It is estimated to reach more than 120 percent in 2021.47

Faced with slowing global growth over the past decades, especially in advanced economies, governments, companies, and households nevertheless increased their debt. Could that have ever been a good idea? Theoretically, yes. When used to invest in productive assets, debt can be a lever of future economic growth and prosperity. But all debt does of course need to be repaid at some point (unless it evaporates because of inflation, but that has been less than 2 percent on average in advanced economies in the past 20 years48). The only alternative is to default, but that is akin to playing Russian roulette.

So what kind of debt has been made in recent decades? The debt of governments is often a mix of high-quality and low-quality debt. High-quality debt includes that used for building modern infrastructure or investments in education, for example. High-quality debt is typically paid back over time—and can likely even provide a return on the investment. Such projects should be encouraged. By contrast, low-quality debt, such as deficit spending to boost consumption, generates no returns, even over time. This type of debt should be avoided.

Overall, it is safe to say low-quality debt is on the rise. In part, this is because low interest rates in the West incentivize lending, which discourages borrowers from being careful with their spending. For governments, deficit spending has become the norm in recent decades, rather than the exception. The COVID crisis that erupted in the early months of 2020 hasn't made that picture any rosier. Many governments have effectively used “helicopter money” to sustain the economy: they printed money, creating an even higher debt with their central banks, and handed it to citizens and businesses in the form of one-off subsidies and consumption checks so they could get through the crisis unscathed. In the short term, this approach was necessary to prevent an even worse economic collapse. But in the long run, this debt too will need to be repaid. Overall, it adds to the large amounts of debt in recent years that wasn't used to spur long-term economic growth or to make the switch toward a more sustainable economic system. This debt will thus remain a millstone, hanging around many governments’ necks.