Полная версия

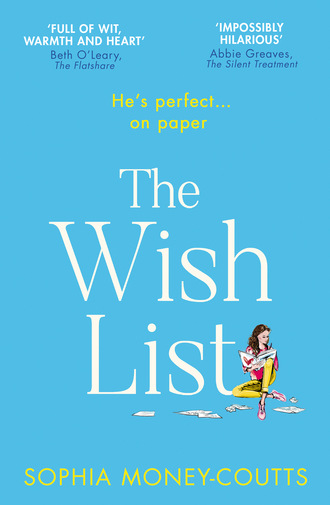

The Wish List

Then there was my colleague Eugene. He was a middle-aged actor who’d worked at the shop for the past decade to pay his rent since he was rarely cast in anything. He had a bald head that shone like a bed knob, wore a bow tie every day and made me rehearse lines with him behind the counter, which often startled customers. Recently, there’d been a dramatic death scene when Eugene, rehearsing for a minor role in King Lear, had ended up lying across the shop floor.

Either he or I opened up before Norris arrived late every morning, his shirt fastened by the wrong buttons, thermos in hand; this was special coffee he ground at home and made in a cafetière before decanting it and solemnly carrying it into work in his satchel. I’d made the mistake of asking what was so wrong with Nescafé not long after I started work there and the cloud that passed his face was so dark I’d wondered if I’d be fired.

Anyway, he’d arrive and there was always grumbling about the traffic or the weather before he went downstairs into his office to drink this coffee from his favourite mug – ‘To drink or not to drink?’ it said on the outside. Half an hour later, he would reappear on the shop floor in cheerier humour and ask whether any customers had been in yet.

But that morning, I was still standing behind boxes of new stock when Norris arrived early and rapped on the glass.

‘You all right?’ I asked, unlocking the door to let him in. He looked more dishevelled than usual, shirt and trousers both crumpled, and he was panting, as if 73-year-old Norris had decided to run into work that morning from his house in Wimbledon.

‘Let me go downstairs for my mug and I’ll be up to explain.’ He strode towards the stairs and disappeared. I returned to the boxes and wondered if he’d tried to get on the Tube using his Tesco Clubcard again.

He thumped back up the wooden stairs not long afterwards and put his coffee on the counter with a sigh.

‘What?’ I asked, frowning. ‘What’s up?’

‘Rent hike.’

‘Another one?’

Norris nodded and wiped his fingers across his forehead. There’d been a rent rise last year but we’d expected that. Uncle Dale had had a long lease on generous terms and it had been up for renewal. Also, Chelsea had changed since he died. What was always a wealthy area of the city had become even more saturated with money: oligarchs from the East, American banking dollars from the West, along with the odd African despot who wanted his children to go to British boarding school. This meant the shops changed. Gone were the boutiques and coffee shops. In came curious replacements selling £150 gym leggings and cellulite cures made from gold leaf – shops for oligarchs’ wives. But although Norris had grumbled about the new lease for several weeks, he’d said it was fine and I’d believed him. It remained business as usual.

But this was different. Norris was panicked.

‘Is it manageable?’

‘I don’t know. It’s a lot,’ he replied, his voice uneven. ‘I’m going to ring the accountant later to discuss it but I wanted to let you know now. Just in case… Well, we’ll see. I’ll let you know.’ Then, as if he couldn’t bear to discuss it any longer, he changed topic. ‘Any post this morning?’

‘Not really. A few orders overnight but I’ll deal with those.’

‘All right, I’m going back downstairs. Shout if you need me.’

‘OK,’ I said, before looking around the shop, trying to imagine it as luxury flats with underfloor heating, marble floors and those hi-tech loos with nozzles that wash and dry your bottom. It was an absurd idea. It couldn’t happen. Not on my watch.

When I got home that night, I found Hugo and Mia bickering at the kitchen table. He’d moved in about six months before, a temporary measure while they did up a house in Herne Hill (‘the new Brixton’, Hugo pompously told anyone who asked).

I had mixed feelings about their house being finished. On the one hand, this meant Mia would move out and, for the first time in a decade, she, Ruby and I would be separated. And although my sisters were closer to one another than they were to me, Mia’s departure would mean change and I’d miss her. On the other hand, it would also mean that Hugo stopped creeping upstairs to my bathroom to do a poo when I wasn’t there. He denied this but I knew he was lying; he left traces on the porcelain and I’d once found a copy of Golfing Monthly lying on the floor.

That evening, they were squabbling over their wedding list and Hugo, his shirtsleeves rolled up to his elbows, was stabbing at the list with one of his weird fingers.

‘Hi, guys,’ I said, making my way to the fridge.

‘I’m sorry you don’t like him,’ went on Hugo, in a high-pitched voice, ‘but he’s my boss and it’s imperative that he’s invited. I’m sure he didn’t mean to graze your bottom. It was probably an accident.’

Mia sighed and leant back from the table. ‘Well he did and we’ve already got half your office. Anyone else you need? The receptionist? The window cleaner? Someone from your IT department?’

‘Actually, Kevin has always been very helpful with my computer.’

I opened the fridge and stared into it as I wondered, for the ninety billionth time, why Mia had said yes to him. Was a house in Herne Hill with an island in the kitchen, underfloor heating in the bathrooms and Farrow & Ball-coloured walls worth it?

She sighed again behind me. ‘Fine. Your boss can come. But that means we still need to lose…’ she went quiet for a few seconds, tapping her pen down the list, ‘about twenty people.’

I closed the fridge. It would have to be eggs on toast. I didn’t have the energy for anything complicated. After Norris’s announcement that morning, he’d stayed downstairs for most of the afternoon, leaving Eugene and me on the shop floor.

I’d leant on the counter, writing a list of ways I could try and help. A petition was my first thought. People always seemed to be launching petitions online. Sign this petition if you think our prime minister should be in prison! Sign this petition to make sugar illegal! Sign this petition to make the earthworm a protected species! I could set up a Facebook page for the shop and launch the petition on there, with a hard copy of it by the till for our less computer-friendly customers. I liked the idea of a cause, imagining myself as a modern-day Emmeline Pankhurst. Perhaps I could wear a sash? Or that might be taking it too far. But a petition, anyway. That was the first thing to organize.

The shop needed an Instagram account, too. Norris still refused to have a mobile phone and insisted that Frisbee could do without social media. I’d long protested, saying that it wasn’t the 1990s, but it had fallen on Norris’s deaf, hairy ears. So, a petition and an Instagram account. Plus, a new website. That was a start.

‘How was your day, Flo?’ asked Mia.

‘Fine. I’m making scrambled eggs. Anyone want some?’

‘No thanks. Wed-shred starts now.’

‘Eggs do terrible things to my stomach,’ added Hugo, but luckily none of us could dwell on this because Mia’s phone rang.

‘Hi, Mum,’ she said, picking it up.

I cracked two eggs into a mug and reached for a fork.

‘Yep, yep, no, I know, yep, we’re doing it now, yep, no, yep…’ she went on while I whisked.

‘Yep, she’s here, hang on,’ said Mia, holding her phone in the air without standing up so I had to cross the kitchen.

I put the mobile to my ear with a sense of dread. ‘Hi, Patricia.’

My stepmother went straight in. ‘I’ve spoken to this woman’s office and she can see you on Tuesday afternoon at five.’

‘Which woman?’

‘The love coach. She’s called Gwendolyn Glossop. Does five on Tuesday work for you?’

‘The shop doesn’t close until six, so—’

‘Florence, darling, you’re selling books, not giving blood transfusions. I’m sure they can spare you for an hour. I’ve told your father and—’

‘All right all right all right. I’ll be there.’

‘Right, have you got a pen? Here’s her address, it’s—’

‘Hang on,’ I said, hunting for a pen on the sideboard. No pens. Why were there never any pens?

‘Floor 4, 117 Harley Street,’ carried on Patricia.

‘OK, I’ll just remember it.’

‘I’m so glad, darling, I do hope she helps. Now can I have Mia back again, I need to talk to her about vicars.’

I handed Mia her phone just as the toast popped up. Black on both sides, a bit like my mood, I thought, sliding them both into the bin.

While Eugene dusted shelves the following morning, I told him about this appointment. He was more enthusiastic than me.

‘Darling, how thrilling,’ he said, his back to me as he swished the pink feathers back and forth like a windscreen wiper. ‘Do you think she’ll have a crystal ball? I saw a palm reader after Angus left and she told me that I’d soon meet the third great love of my life.’

‘And did you?’

‘No.’ He lowered the duster and held his palm close to his nose, inspecting it. ‘It’s this line that runs from your little finger.’ He looked up. ‘But perhaps I just haven’t met him yet? I expect he’ll be along any second, waiting for me on the 345 bus.’

I wasn’t sure about that. I’d never seen anyone who looked like a great love on the 345, so I merely nodded and Eugene returned to his dusting.

Angus was Eugene’s ex-boyfriend, the second great love of his life after Shakespeare, he always said. They’d met while studying drama at university and had been together for twenty years, but not long after I started working at Frisbee, Angus moved to New York to direct a performance of Evita and they’d separated. He’d remained there since and was now considered one of Broadway’s top musical directors while, back in London, Eugene constantly auditioned for roles he never got.

Barely a day went by when he didn’t mention Angus, as if a proud parent watching his offspring blossom from afar. He kept up with his shows, read his New York Times reviews out loud to me in the shop and occasionally emailed him to say congratulations. I was never sure if Angus replied to these, I didn’t like to ask. Still, Eugene was one of life’s sunbeams, a positive person who remained admirably upbeat in the face of these disappointments, so his enthusiasm towards Gwendolyn Glossop didn’t surprise me.

‘So you think I should definitely go and see this woman? It isn’t a bit… tragic? Or mad?’

Eugene tutted. ‘Absolutely not. What have you got to lose?’ He turned back to me and held the duster high in the air. ‘Boldness be my friend.’

‘What’s that?’

‘Cymbeline, act one. And I think you should look upon this as an exciting opportunity.’ He spun to face me again. ‘Because without meaning one jot of offence, angel, I think my mother gets more action than you.’

‘Doesn’t your mother live in a retirement home?’

‘In Bournemouth, exactly my point.’

I was about to object but heard Norris’s heavy footsteps on the stairs.

He glanced from Eugene to me, tufty eyebrows raised. ‘You two all right up here?’

‘We are indeed,’ said Eugene. ‘I’m just advising our young colleague on matters of the heart.’

Norris had been married decades ago to a lady called Shirley but now lived alone. On quiet days in the shop, Eugene and I sometimes speculated about his private life. Had Shirley run off with the postman, driven away by Norris’s gruffness? Had waking up beside that amount of ear hair become too much to bear? Had Shirley given up life in an untidy Wimbledon flat for a dashing younger man on the Costa Del Sol? Eugene’s dramatic nature meant he tended to get quite carried away with these speculations but we remained none the wiser. Norris wasn’t the sort to discuss anything emotional.

‘I don’t want to know,’ he said, waving his hands in the air as if protesting. ‘I just came up for the post.’

I handed it over to him and mouthed ‘Shhhh!’ at Eugene. The fewer people who knew about my appointment with Gwendolyn, the better.

The following Tuesday, I arrived at 117 Harley Street and was told by a receptionist to take the lift to the fourth floor.

‘Are there any stairs?’ I hated the jerkiness of lifts in old London buildings like this, clanking and creaking like a dodgy fairground ride.

‘Take the fire exit next to the lift,’ instructed the receptionist, not looking up from her magazine.

I played Consequences as I walked up. If the steps were even, it would be a helpful hour, which made me feel less freakish for never having had a boyfriend. But what would it be if the stairs were odd? What was the worst outcome of this session? If they were odd numbers, I’d never have a relationship and I’d become one of those little old ladies you see shopping by themselves in the supermarket, hunched over a wheelie trolley and buying tins of fish paste for their solo suppers.

The first flight had thirteen stairs and I felt a spasm of panic. The next two had eleven and the last nine. Disaster.

I walked along a corridor which smelt of instant coffee and stopped at the door with a small sign that said ‘Gwendolyn Glossop, MS, Love Coach and Energy Healer.’

I knocked.

‘Come i-hin!’ came a high-pitched voice.

I pushed it open to find a salmon-pink room. Salmon-pink walls, salmon-pink curtains, salmon-pink sofa and armchair. On the sofa were four cushions – two shaped like red hearts and one which had the letters ‘LO’ on it beside another that said ‘VE’. Grim.

Decorating a wooden dresser behind this sofa were several statues of naked women. My eyes slid along them. Nineteen in total, with rounded bottoms and pert breasts. Wooden statues, bronze statues, statues carved from stone, even a purple wax statue, although that one had started melting and was headless. On the opposite wall was a mural of clouds and classical figures in togas. It was as if I’d stumbled through the back of a wardrobe, from the clinical starkness of Harley Street into a deranged computer game.

‘Welcome, Florence,’ said Gwendolyn, pushing herself up from the armchair. She was a large woman wearing purple dungarees that fastened with buttons shaped like daisies. Silver earrings dangled from her ears and she had the sort of cropped haircut you get when you join the army. The tips of her eyelashes were coated with blue mascara and the look was completed with a pair of green Crocs.

She pointed at a woman in the mural, a brunette whose toga had slipped off one bosom but not the other. ‘That’s Aphrodite, the goddess of sexual pleasure. Are you familiar with her?’

‘No, I don’t know her, er, work.’

‘Ah, never mind.’ We shook hands, a row of bangles dancing up and down Gwendolyn’s forearm, and she gestured at the sofa. ‘Please have a seat.’

She reached for a pad of paper and a pen from a coffee table while I leant back against the cushions and tried to relax. All the pink made me feel like I was sitting in someone’s intestines.

‘And how are we today?’ Gwendolyn asked, glancing up from her pad with a smile.

‘All right.’

‘Not nervous?’

‘No,’ I fibbed. This was mad. This room was mad. This woman was mad. Patricia was mad. I pretended to scratch my wrist so I could push up the cuff of my jumper and look at my watch: fifty-eight minutes to go.

‘I’m going to ask a few preliminary questions before we get stuck into the real work,’ said Gwendolyn, raising her chin and cackling before dropping it and becoming serious again. ‘Can you tell me why you’re here?’

‘Because I have a socially ambitious stepmother who thought it would be helpful, so I said I’d try this out so long as she never interrogated me about my love life again,’ I replied. I might as well be honest.

Gwendolyn cackled again and scribbled a note. ‘And can you tell me about your relationship history?’

‘Not much to tell. There was someone briefly at university ten years ago. Very briefly. But that’s pretty much it.’

‘Nobody else?’ said Gwendolyn, her forehead rippling with concern.

I picked at a scrap of cuticle on my thumb then met her gaze. ‘A few one-night things. But nothing more than that. I’d like to fall in love,’ I said, trying to sound casual, as if I’d just said I’d like a cup of tea. ‘Course I would. But the right person hasn’t come along.’

‘Mmm,’ murmured Gwendolyn, looking from me to her pad. She shifted in her armchair and crossed her right ankle over her left knee so a Croc dangled from her foot. She looked up and squinted, as if she was trying to see inside me, then back at the list. ‘Mmm, yes, what I think we need to do is clear your love blocks out. I can sense them. Your subconscious is very powerful. You’re stuck. Hurting. Lonely. Do you want to stay lonely, Florence?’

But before I had a chance to reply and say I wasn’t lonely and, actually, I quite liked going to bed at whatever time I wanted, Gwendolyn ordered me to lie back on the sofa and close my eyes.

‘Across the whole thing?’

‘Yes, yes, stick your legs over the end. That’s it. Put a cushion under your head. There we go.’

Resting my head on a heart-shaped cushion, I noticed a cherub painted on the ceiling. I closed my eyes to banish it, wondering how many minutes were left now.

‘I’ll light a candle to dispel the forces of darkness and then we’ll get going,’ she said. ‘Eyes closed.’

I shut them as she started asking questions in a velvety voice. ‘What grievances are you hanging on to, Florence? What can you let go?’

I thought about replying ‘trapped wind’ but suspected Gwendolyn wouldn’t find this funny. Then I smelt herbs so opened one eye again; she was circling her hands around my face without touching it, as if my head was a crystal ball.

‘What’s that smell?’

‘It’s sage and frankincense oil for emotional healing. But forget the herbs. Close your eyes and think, who are you holding on to in your heart? Can you let them go?’

The questions continued while Gwendolyn wafted her oily fingers above my face.

‘Set an intention for your healing. Ask yourself: what do I need right now to open my heart to the love I deserve?’

I wondered what to have for supper when I got home. I was starving. Soup? The thought of ending a day with soup was depressing.

‘We need to break down the wall around your heart,’ she went on. ‘Imagine a bulldozer smashing that wall, Florence, opening the path to true intimacy.’

A baked potato? No, it would take too long and I hated it when they weren’t cooked in the middle.

‘Now open your eyes and sit up, and we can make a start,’ said Gwendolyn. ‘I’ve cleared those blocks and you should be feeling clearer and calmer. Less defensive.’

I opened my eyes feeling exactly as I had nine minutes earlier.

Wiping her hands with a tissue, Gwendolyn explained that she wanted me to write a list.

‘A list? Like a shopping list?’

Gwendolyn nodded, the silver teardrops swinging in her earlobes. ‘Exactly, my precious. Like a shopping list, except for what you want from a man, not Asda. Ha ha!’ Her mouth opened wide at her own joke before she was serious again. ‘What do you want in a man, Florence?’

‘Er…’

‘Because you need to ask the universe for it,’ she said solemnly. ‘These things don’t just fall into our laps. You need to manifest your desires and attract the right vibrations into your life, summon them to you.’ Gwendolyn stretched her arms in front of her and pulled them back as if playing a tug of war with these vibrations.

‘OK,’ I replied. I was going to play along with this mad hippie. Play along for the session then leave and tell Patricia that she was never, ever to interfere with my love life again.

Gwendolyn tore a piece of paper from her pad and handed it to me. ‘Use a book to lean on.’

I reached underneath the glass table for the nearest book, which had a silhouette of a cat on the front. The Power of the Pussy: How To Tame Your Man, said the title. I covered it quickly with my piece of paper. The power of the pussy indeed. Marmalade would be horrified.

‘Help yourself to a pen,’ went on Gwendolyn, ‘and I want you to write down the characteristics that are important to you so the universe can recognize them and deliver what you’re looking for.’

‘How many characteristics does the universe need?’

‘As many as you like, poppet,’ she replied, flourishing a hand in the air like a flamenco dancer. ‘But the more specific the better. Don’t just say “handsome”. The universe needs clear instructions. Write down “has all his own hair”. Don’t say “athletic”. Say “goes to the gym once or twice a week”. Remember, it’s your list. Your wish list for the universe to answer.’

I wished she’d stop talking about the universe. I went quiet and blinked at my piece of paper. What to write? I couldn’t possibly take this seriously, but on the other hand, I had to write something to convince this nutter that I’d at least thought about it.

After twenty minutes of sighing, chewing the biro, nearly swallowing the little blue stopper at the end of the biro, laughing to myself, closing my eyes and shaking my head before sighing again, I’d come up with a few suggestions. I totted them up and felt uneasy. That was fifteen. I needed one more to make it even. I gnawed the end of the biro once more and thought of a final addition.

THE LIST

– LIKES CATS.

– INTERESTING JOB. NOT GOLF-PLAYING INSURANCE BORE LIKE HUGO.

– BOTTOM AND SEXUAL ATHLETICISM OF JAMES BOND.

– NICE MOTHER.

– NO POINTY SHOES.

– NO HAWAIIAN SHIRTS.

– NO UMBRELLAS.

– READS BOOKS. NOT JUST SPORTS BIOGRAPHIES.

– NO REVOLTING BATHROOM HABITS. E.G. SKID MARKS.

– AMBITIOUS.

– ADVENTUROUS.

– GOOD MANNERS. E.G. SAYS THANK YOU IF SOMEONE HOLDS THE DOOR OPEN FOR HIM.

– ISN’T OBSESSED WITH INSTAGRAM OR HIS PHONE.

– FUNNY.

– ACTUALLY TEXTS ME BACK.

– DOESN’T MIND ABOUT MY COUNTING.

I handed the piece of paper to Gwendolyn who inspected it while I checked my watch. In twelve minutes, I could go home for supper, whatever it was. Eggs again? Could one overdose on eggs?

‘Well,’ said Gwendolyn, looking up. ‘You clearly listened to what I said about being specific. This line about James Bond, for instance…’

I spread my hands in mock innocence. ‘You said it was a wish list. So I thought, why not? If I can truly put down any bottom I wanted, why not go for his?’

The corners of Gwendolyn’s mouth tightened as she glanced back at the list. ‘What’s wrong with umbrellas?’

‘Not very manly,’ I said. I had a thing about this. Hugo never left the house without his umbrella. It seemed fussy and faint-hearted; you’d never catch Mr Rochester or Rhett Butler faffing about with an umbrella.

‘And you want someone who’s both ambitious and adventurous?’

I nodded. Ambition was to guard against the sort of man whose dreams stopped at ‘golf club membership’ and someone with a spirit of adventure might encourage me to be braver, to venture further afield than south London.

‘Fine,’ she went on, ‘but you could jot down a few more personality characteristics. What about kindness, or generosity? And does he want children?’