Полная версия

Post Wall, Post Square

The Soviet leader also elaborated on his vision of a Common European Home. This ruled out ‘the very possibility of the use or threat of force’ and postulated ‘a doctrine of restraint to replace the doctrine of deterrence’. He envisaged, as the Soviet Union moved towards a ‘more open economy’, the eventual ‘emergence of a vast economic space’ right across the continent in which the ‘eastern and western parts would be strongly interlocked’. He continued to believe in the ‘competition between different types of society’ and saw these kinds of tensions as ‘creating better material and spiritual conditions of life for people’. But he was looking forward to the day when ‘the only battlefield would be markets open for trade and minds open to ideas’.

Admitting that he had ‘no finished blueprint’ in his pocket for the Common European Home, he reminded his listeners of the work of the 1975 Helsinki Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe (CSCE), when thirty-five nations had agreed common principles and values. It was now time, he declared, for the present generations of leaders in Europe and North America ‘to discuss, in addition to the most immediate issues, how they contemplate future stages of progress towards a European Community of the twenty-first century’. At the cornerstone of Helsinki 1975 were the two superpowers and, Gorbachev believed, that situation had not changed. ‘The realities of today and the prospects for the foreseeable future are obvious: the Soviet Union and the United States are a natural part of the European international and political structure. Their involvement in its evolution is not only justified, but also historically conditioned. No other approach is acceptable.’[56]

Gorbachev returned home via Romania, where he led a Warsaw Pact meeting that formally and publicly renounced the Brezhnev Doctrine – in other words cementing his statements in New York and more recently Strasbourg that force would not be used to control the development of individual socialist states. Combined with Gorbachev’s PR offensive of drastic, unilateral Soviet force reductions in Eastern Europe and his express desire for the Warsaw Pact states to make progress with NATO countries on producing a conventional arms accord by 1992,[57] this was another deeply worrying moment for Honecker and the other hardliners in the bloc – Ceaușescu and Miloš Jakeš of Czechoslovakia – especially considering that they had used the summit to lobby vehemently for Warsaw Pact military intervention in Hungary. Champions of repression and intransigence, they must have felt that the Kremlin was abandoning them.[58] Gorbachev certainly left his fellow communist leaders in no doubt what he thought about the dinosaurs among them. He stressed that ‘new changes in the party and in the economy are needed … Even V. I. Lenin said that new policies need new people. And this does not depend on subjective wishes any more. The very process of democratisation demands it.’[59]

The Soviet leader left Bucharest on 9 July, just as the president of the United States was arriving in Warsaw. Each superpower was putting down markers on a Europe in turmoil.

*

Bush had been alarmed by the Soviet leader’s peace offensive around Europe, not least because America’s NATO allies appeared to be in the grip of some kind of ‘Gorbymania’ which made them susceptible to Soviet blandishments about arms reduction. His own European tour – to Poland and Hungary ahead of the G7 meeting in France – had been planned in May but it was now all the more imperative, in order to ‘offset the appeal’ of Gorbachev’s message.[60]

Indeed, before even setting off for Europe, Bush made a point of quickly and strongly rebuffing Gorbachev’s Paris proposals: ‘I see no reason to stand here and try to change a collective decision taken by NATO,’ he declared, and reiterated that there would be no talks on SNFs until agreement had been reached in Vienna on reducing conventional forces in Europe, an area in which the USSR was vastly superior. He wrote sarcastically in his memoirs about Gorbachev’s attempt to persuade the West that it ‘need not wait for concrete actions by the Soviet Union before lowering its guard and military preparedness’.[61]

That said, Bush did not want his European trip to be about scoring points off Gorbachev. The president had already laid down his own ideological principles in the spring and, far from wishing to mount a ‘crusade’, he was sensitive both to the volatile situation in Eastern Europe and to Gorbachev’s delicate political position at home. He did not intend to ‘back off’ from his own values of freedom and democracy but was acutely conscious that ‘hot rhetoric would needlessly antagonise the militant elements within the Soviet Union and the Pact’. He even worried about the impact of his own presence, regardless of what he said. While wanting to be what he called a ‘responsible catalyst, where possible, for democratic change in Eastern Europe’, he did not want to be a stimulus for unrest: ‘If massive crowds gathered, intent on showing their opposition to Soviet dominance, things could get out of control. An enthusiastic reception could erupt into a violent riot.’ Although he and Gorbachev were jockeying for position, the two leaders agreed on the importance of stability within a bloc that was in flux.[62]

Bush and his entourage arrived at Warsaw’s military airport around 10 p.m. on 9 July. It was a humid summer evening as they descended from Air Force One to be greeted by a large official welcoming party. Jaruzelski was in the forefront but, for the first time ever during a state visit, representatives of Solidarity were also present. No spectators were allowed near the plane, but en route from the airport to the government guest house in the city centre, where George and Barbara Bush would be staying, thousands of people lined the streets, three or four deep, waving flags and giving the Solidarity ‘V’ for victory symbol. Others leant from the balconies of their apartments, throwing down flowers onto the passing motorcade. The mood, contrary to Bush’s fears, was that of a friendly welcome, not a political demonstration.[63] In fact, this was typical of the whole trip. There were no massed throngs cheering in adulation – nothing like Pope John Paul II in 1979 or Kennedy in Berlin in 1963. The public mood seemed uncertain, characterised by what American journalist Maureen Dowd called a mixture of ‘urgency and tentativeness’ as Poles contemplated a strange future in which the ‘jailors’ and those they had jailed would now have to try to govern together.[64]

Bush and Jaruzelski managed to turn their scheduled ‘ten-minute cup of coffee’ in the morning of 10 July into an extended and frank conversation that lasted almost an hour. Their tour d’horizon spanned Polish politics and economic reforms, US financial aid, superpower relations, the German question and Bush’s vision of ‘a united Europe without foreign troops’.[65] The president’s meeting with Prime Minister Mieczysław Rakowski – a veteran communist journalist until he was suddenly appointed premier the previous September – was similarly businesslike and also opened up some of the complexities underlying the glib word ‘reform’. Poland’s ‘chief problem’, Rakowski explained, was to ‘introduce reforms while avoiding serious unrest’. Privatisation would be an important step but he warned it would take ‘a full generation’ before Poles accepted the Western-style ‘stratification of wealth’ that would necessarily follow. What Polish people did not need, he added, was an American ‘blank check’ – in other words ‘untied credits’ from the West. Instead he hoped Bush could encourage the World Bank and IMF to display flexibility about the staggering of debt repayments. Rakowski conceded his party’s ‘economic errors of the past’ but insisted that these ‘constitute a closed chapter’ and that Polish leaders now understood the need to turn the page. Bush promised that the West would help but stated that he had no intention of supporting the radical, indeed frankly utopian, demands by the labour unions that would ‘break the Treasury’. In that way Bush stood closer to the aims of Polish communist reformers including Jaruzelski and Rakowski, who sought managed economic cooperation with the USA and the West, than to Wałęsa and the opposition, who wanted immediate and large-scale direct aid to ease the pain of transition and thus maintain popular support.[66]

The president did talk about economic aid when he addressed the Polish parliament on the afternoon of the 10th, but what was grandly described as his ‘Six-Point Plan’ received a mixed reception. To be sure, the need was clear: Poland’s debt to Western creditors in summer 1989 stood at around $40 billion, with the country’s growth rate barely above 1% while inflation was running at almost 60%. But although Bush promised to ask the US Congress for a $100 million enterprise fund to invigorate Poland’s private sector, he hoped that the rest of the aid package he proposed ($325 million in fresh loans and a debt rescheduling of $5 billion) would come from the World Bank, the Paris Club, the G7 and other Western institutions.[67] It was all a bit vague and certainly nothing like the $10 billion that Wałęsa, for one, had requested. Nor did it even come close to the $740 million in aid that Reagan, at the height of the Cold War, had offered the communist government before martial law was declared in December 1981.[68] That, of course, was prior to the USA’s foreign debt going through the roof as a result of Reaganomics – from $500 billion in 1981 to $1.7 trillion in 1989.[69] Certainly the public reaction in Poland was almost openly critical. ‘Very little concrete material’, a government spokesman complained, and ‘too much repeated emphasis on the need for further sacrifices by the Polish people’. So much for popular hopes in Poland of a ‘mini-Marshall Plan’. While Bush saw himself as being ‘prudent’, Scowcroft told journalists defensively that the value of the aid was ‘political and psychological’ as much as ‘substantive’.[70]

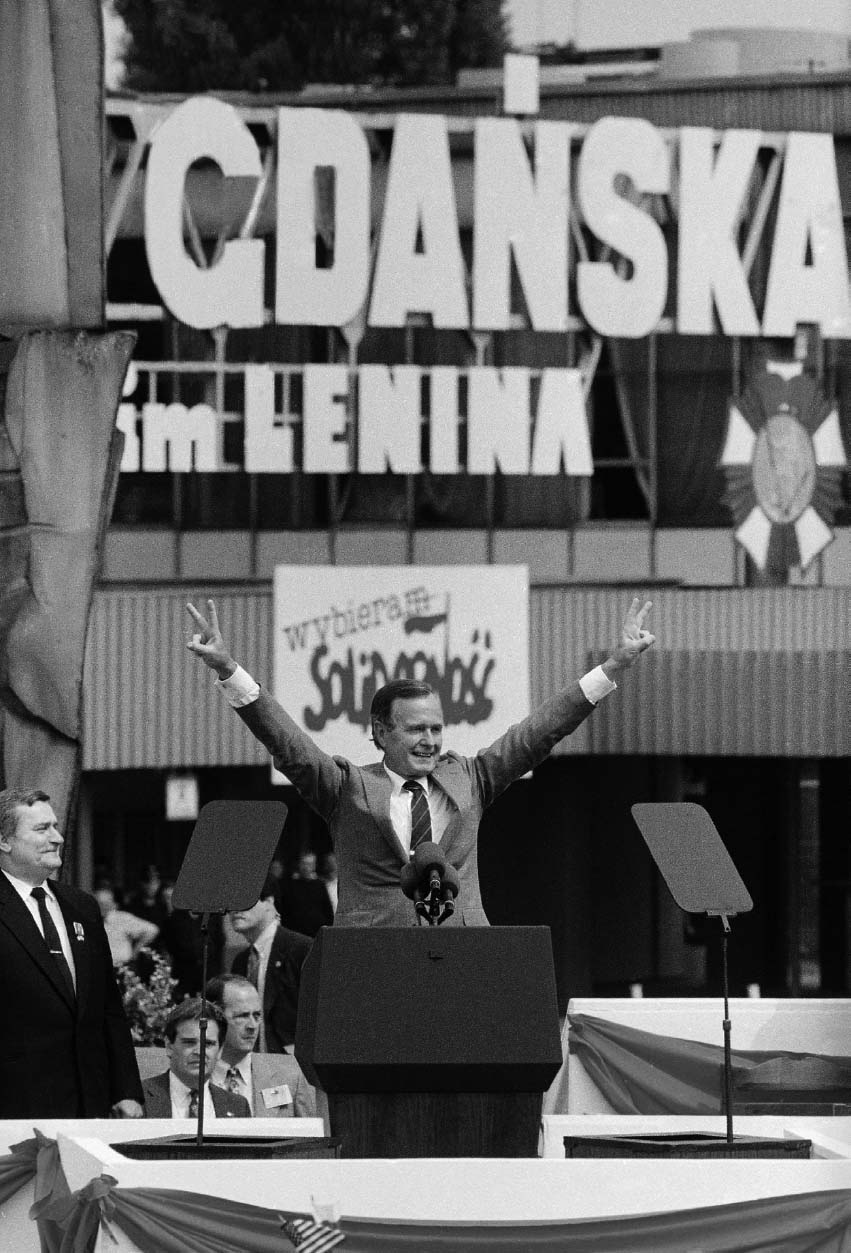

Next day Bush flew to Gdańsk to meet Wałęsa for lunch at his modest but cosy two-storey stucco house on the outskirts of the city. This was a deliberately informal, down-home affair. George and Barbara chatted with Lech and Danuta as ‘private citizens’, because the Solidarity leader had not stood for election and therefore had no official political role now. Looking around the rooms, the president was struck by the ‘lack of modern appliances and furnishings that most American families take for granted’. ‘Stylish waiters’ borrowed from a nearby hotel and a ‘fancy’ Baltic meal served on silver salvers did not cover up those realities. After more of what Bush described as Wałęsa’s ‘uncertain and unrealistic’ financial requests, backed by lurid warnings of ‘a second Tiananmen in the middle of Europe’ if Polish economic reforms failed, the president was happy to escape from their uneasy get-together and drive to the Lenin Shipyard to address 25,000 dockworkers. He considered standing outside the factory gate in front of the monument commemorating the forty-five workers killed by the security forces during the 1970 strikes – three anchors nailed to giant steel crosses – the ‘emotional peak’ of his Polish trip. Bush felt ‘heart and soul, emotionally involved’ as he spoke, with a ‘heady sense’ that he was ‘witnessing history being made on the spot’.[71]

Trumping Lenin in Gdańsk – Bush with Wałȩsa

His trip to Poland had been brief (9–11 July) but it underlined the magnitude of the political and economic problems that had to be surmounted. One presidential adviser told the press, it would ‘take hundreds of millions of dollars, from us and lots of other people, and even that won’t guarantee success’.[72]

That evening Bush arrived in Budapest during a heavy thunderstorm. He and Barbara were driven straight to Kossuth Square – named for the leader of Hungary’s failed revolution of 1848 and one of the centres of the 1956 uprising against Soviet rule. As the motorcade pulled into the square in front of the Parliament building it was greeted by a huge mass of people, some 100,000 strong – a crowd in an ebullient mood, full of expectation, despite being drenched by the rain. Bush, too, was very excited. It was the first ever visit of an American president to Hungary.[73]

The rain continued to fall while Hungary’s president Bruno Straub droned on for a full quarter-hour of plodding introductions. When Bush finally got a chance to speak, he waved away an umbrella, dispensed with his notecards and made a few extempore remarks ‘from the heart’ on the changes taking place in Hungary and on its reform-minded leadership. Just as he finished, the evening sun broke through the dark clouds. There was another special moment. Out of the corner of his eye, Bush noticed an elderly lady near the podium who was soaked to the skin. He took off his raincoat (which actually belonged to one of his security agents) and put it round her shoulders. The spectators roared with approval. Then Bush plunged into their midst, shaking their hands and shouting good wishes. Scowcroft noted: ‘The empathy between him and the crowd was total.’[74]

Next day, 12 July, Bush followed a similar script to his Warsaw visit. He was careful not to be seen associating with any opposition-party officials too closely. Indeed his meetings with both opposition and Communist Party figures were behind closed doors while in public he expressed his support for the communist reformers who now ran the government. Still, the difference in overall atmospherics between Budapest and Warsaw was clear: Hungary had enjoyed for two decades ‘more political freedom – nightclubs feature biting satirical sketches about the government – and more economic energy, with food markets piled high with fruits and vegetables, than the other Warsaw Pact countries’.[75]

In his talks with Bush, Prime Minister Miklós Németh emphasised his firm belief that the Hungarian Socialist Workers’ Party (HSWP) could ‘renew itself and will be able to, through electoral means, gain a dominant position in the coalition. The danger is that if the HSWP is defeated, the opposition is not yet ready to rule.’ Bush agreed. As regards the ‘political system for Hungary’, the president stated that ‘the principles articulated by the prime minister are ones that Americans support’ and promised that he would ‘do nothing to complicate the process of reform’. Being inclined toward stability, Bush believed that it was the reform communists who were uniquely equipped to successfully engineer a gradual exit from Moscow’s orbit.[76]

In Hungary – unlike Poland where the political situation was rather precarious in the wake of the elections – the question was not whether reform would proceed but how fast and on whose terms. Currently the reform communists were driving the transformation, and they did so with confidence. Internationally Hungary had more room for manoeuvre than Poland, a strategically more pivotal country for the Soviet Union. And Budapest also knew that it benefited from following in Warsaw’s slipstream. Poland had clearly managed to get away with its reform course by staying within the Warsaw Pact, and the Hungarian reformers also saw this as the best path – especially after Gorbachev had held firm to his non-interventionist position in the Bucharest summit. (Leaving the Warsaw Pact had been the step too far by Hungary in 1956.)

Understanding the new rules of the game, Hungarians were also willing to test the limits of the possible. In fact, they had done so already with the dismantling of the barbed wire. As Imre Pozsgay – effectively Hungary’s deputy prime minister under Németh – explained to Bush, there were only two situations that might attract Soviet intervention: ‘the emergence of civil war’ or ‘a Hungarian declaration of neutrality’. The former he deemed unlikely: he was sure Hungary would undergo a ‘peaceful’ transformation. And the latter was simply ‘not possible’ for Hungary: as in Poland’s case, Hungary’s Warsaw Pact membership was non-negotiable to avoid provoking the Kremlin. Bush entirely agreed that Hungarians should not have to choose between East and West. What was important, he declared, was ‘for Soviet reforms to go forward’ while the United States did not ‘exacerbate Gorbachev’s situation or make the Hungarian course more difficult’.[77]

Bush found the reformers’ buzz and energy infectious. Quite contrary to a Poland that had seemed drab, subdued and worried about its new political pluralism, Hungary, opening rapidly towards the West, seemed really full of vitality. And Bush conveyed this in his speech at Karl Marx University on the afternoon of 12 July. ‘I see people in motion,’ he said. ‘I see colour, creativity, experimentation. The very atmosphere of Budapest is electric, alive with optimism.’ Bush wanted his words to act as an accelerator of the process of change ahead of the multiparty elections, so the country would not get stuck in half-measures. ‘The United States will offer assistance not to prop up the status quo but to propel reform,’ he declared, before reminding his audience that here, as in Poland and across the bloc, simple solutions did not exist: ‘There are remnants of the Stalinist economy – huge, inefficient industrial plants and a bewildering price system that is hard for anyone to understand, and the massive subsidies that cloud economic decisions.’ But, he added, ‘the Hungarian government is increasingly leaving the business of running the shops to the shopkeepers, the farms to the farmers. And the creative drive of the people, once unleashed, will create momentum of its own. And this will … give each of you control over your own destiny – a Hungarian destiny.’[78]

In spite of this passionate rhetoric, as in Warsaw the president offered relatively meagre economic aid: $25 million for a private-enterprise fund; $5 million for a regional environmental centre; the promise of ‘most favoured nation’ status as soon as Hungary liberalised its emigration laws. He also made much about sending a delegation of Peace Corps volunteers to teach Hungarians English.[79]

His audience listened quietly but intently throughout the address. The most emotional moment was Bush’s comments on ‘the ugly symbol of Europe’s division and Hungary’s isolation’ – the barbed-wire fences that, he said, were being ‘rolled and stacked into bales’. Bush declared grandly: ‘For the first time, the Iron Curtain has begun to part … And Hungary, your great country, is leading the way.’ What’s more, with the Soviet Union withdrawing troops, he promised, ‘I am determined that we will work together to move beyond containment, beyond the Cold War.’ He ended ringingly with the invocation: ‘Let us have history write of us that we were the generation that made Europe whole and free.’ It won him a standing ovation.[80]

*

On Thursday 13 July, as Bush flew from Budapest to Paris for the G7 summit, he and Scowcroft reflected on the ‘new Europe being born’. During the flight the president also shared his impressions with members of the press corps, huddled around him on Air Force One. He said he had come away with ‘this real acute sense’ of the change that was taking place in Eastern Europe – a change he described as ‘absolutely amazing’, ‘vibrant’ and ‘vital’. He declared his determination to ‘play a constructive role’ in that process of change. The meetings, especially with the Hungarian leaders, had been ‘very good, very frank’. Warming up, Bush added, ‘I mean it was with emotion, and it wasn’t your traditional “I’ll read my cards, and you read your cards” kind of diplomacy.’ There had been ‘an intensity to it, a fervour to it’ that, he said, ‘moved me very much’.[81]

The president had no idea what lay ahead and so he remained cautious, but he was certainly encouraged by what he had seen. ‘I am firmly convinced that this wave of freedom, if you will, is the wave of the future,’ said Bush buoyantly. To some, it seemed that he was too cautious and overly sympathetic to the communist old guard. Yet others, including his deputy national security adviser Robert Gates, argued that the president was playing a more complex game. While preaching democratic freedoms and national independence to the crowds, he talked the language of pragmatism and conciliation to the old-guard leaders – in a deliberate attempt to ‘grease their path out of power’.[82]

Certainly, the challenge faced by his administration was to encourage reform in Eastern Europe without going so far and fast as to provoke turmoil and then a backlash. A fraught economic transition could easily result in inflation, unemployment and food shortages – all of which would force reform-oriented leaders to reverse course. Above all, Bush wanted to be sure to avoid triggering a Soviet reaction – possibly a crackdown in the style of 1953, 1956 and 1968. The key to successful change in the Soviet bloc was Soviet acquiescence, and Bush was keen to make it easy for Gorbachev to provide this. ‘We’re not there to poke a stick in the eye of Mr Gorbachev,’ he told the reporters. ‘Just the opposite – to encourage the very kind of reforms that he is championing and more reforms.’[83]

Fresh from witnessing revolutionary change, Bush arrived in a city obsessed with commemorating revolution. 14 July 1989 would mark the bicentenary of the fall of the Bastille, the starting point of France’s quarter-century roller coaster of demotic politics and imperial autocracy. French president François Mitterrand was determined to impress his international guests with an extravagant celebration of French grandeur – and his own quasi-regal position. Yet, given the dramatic upheavals in Eastern Europe, France’s historical pageant had particular resonance in July 1989.

As soon as Bush arrived, he was whisked off to the Place du Trocadéro opposite the Eiffel Tower. He sat with the six other leaders of the major industrialised nations, together with over twenty leaders from developing countries in Africa, Asia and the Americas, for a ceremony to commemorate the 1789 Declaration of the Rights of Man. Actors read excerpts from the declaration and quotations from the revolutionary leaders, wreaths were laid at a stone inscription of the document and 500 doves were released into the blue Paris sky. Mitterrand’s intent was clear: France’s pioneering revolution was to be remembered not for the blood in the gutters but for its enduring values: liberté, fraternité, égalité. Then followed an evening at the brand-new, gleaming mammoth Opera House in the Place de la Bastille, on the site of the once-dreaded royal prison. On this occasion too Mitterrand’s special twenty guests were present, together with the leaders of the G7 – as they were for the Bastille Day Parade the next morning, when the French president put on a massive display of France’s ‘world class’ military prowess down the Champs-Elysées. Nobody could mistake the implicit message: the Fifth Republic was still a power with global reach. Watching 300 tanks, 5,000 troops and a mobile nuclear missile unit go by along Paris’s grand boulevard, Scowcroft couldn’t help being reminded of ‘a Soviet May Day parade’.[84]

Mitterrand’s friends from the Third World really irritated the Americans. After all, the Paris G7 economic summit had been prepared especially to deal with the pressing issues of debt relief and the global environment. But the US delegation emphatically did not want to get the G7 meeting conflated with an impromptu North–South gathering on the margins of the French national celebrations, especially after the debtor countries had already seized the spotlight in Paris to appeal for relief from the developing world’s $1.3 trillion debt. The White House worried about the risk that in such an ex tempore meeting between creditors and debtors, as advocated by France, the ‘South’ as a bloc would dress up their demands to the ‘North’ as ‘reparations’ for years of colonial ‘exploitation’, laced with Marxist–Leninist-inspired rhetoric. And generally, the US strongly opposed collective debtor action. In its view, debt problems should be resolved country by country and in this vein the Americans announced a $1–2 billion short-term loan to neighbouring Mexico and then picked up the case of Poland.[85]

Given the G7 summit’s central focus on debt relief, General Jaruzelski saw his opportunity and appealed to the Big Seven for a two-year, multibillion-dollar rescue programme on 13 July. Published in all major Polish party newspapers, his six-point programme included seeking $1 billion to reorganise food supplies, $2 billion in new credits, as well as a reduction and rescheduling of Poland’s debt of roughly $40 billion, plus financing for an assortment of specific projects. Significantly, the Solidarity movement endorsed Jaruzelski’s appeal; indeed, Wałęsa had just come out in support of an approved Communist Party candidate for the presidency, which made General Jaruzelski’s victory much more likely – thus helping to end the political deadlock of the post-election weeks.[86]