Полная версия

Post Wall, Post Square

The last of Kohl’s big calls – and the most sensitive of all – was with Gorbachev, before lunch on 11 November. Kohl set out some of the grave economic and social problems now facing the GDR, but stressed the positive mood in Berlin. Gorbachev was less testy than in his initial message to Kohl the previous day and expressed his confidence in the chancellor’s ‘political influence’. These were, he said, ‘historical changes in the direction of new relations and a new world’. But he emphasised the need above all for ‘stability’. Kohl firmly agreed and, according to Teltschik, ended the conversation looking visibly relieved. ‘De Bärn is g’schält’ (‘The pear has been peeled’) he told his aide in a thick Palatinate accent with a broad smile: it was clear that Gorbachev would not meddle in internal East German affairs, as the Kremlin had done in June 1953.[15]

Kohl could now feel reassured about his allies and the Russians, yet these were not his only worries. As he got off the phone he must have reflected on his own Deutschlandpolitik – its future direction and the responsibilities that now weighed heavily on him. All the more so, given what he had learned in Cabinet that morning about just how unstable the situation really was.

So far that year, according to the Interior Ministry, 243,000 East Germans had arrived in West Germany, as well as 300,000 ethnic Germans (Aussiedler) who could claim FRG citizenship: in other words, well over half a million immigrants in ten months. And this was before the fall of the Wall. The economic costs were also escalating. According to the Finance Ministry, DM 500 million had to be added to the budget in 1990 just to provide emergency shelters for the recent influx of GDR refugees. And an additional DM 10 billion a year for the next ten years might be required to build permanent housing and provide social benefits and unemployment payments. Moreover, the FRG was already subsidising the GDR economy to the tune of several billion a year. And far more would clearly be needed if the GDR were to be propped up sufficiently to stem the haemorrhage of people. But for how long could it be sustained? And what would happen if Germany unified? Revolution was certainly turning the East upside down, but life for West Germans was evidently changing as well – and not all those changes were welcome.[16]

Even if, in the short term, such spending on the GDR and on the migrants was economically feasible, any talk of raising taxes to cover the costs was politically impossible for Kohl and his coalition partners in an election year. The recent rise in the FRG of the Republikaner (the radical right’s new party) reflected growing resentment at the immigrant crisis and dismay at the financial burden to be carried by West German citizens.[17]

Although Kohl had talked about ‘stability’ to Gorbachev and to his Western allies, as he flew back to Warsaw on the afternoon of 11 November to pick up the threads of his Polish visit, he must have seen how difficult it would be to keep the GDR functioning. But, of course, he had no real desire to do so in the longer run. The ‘stability’ he was now beginning to contemplate was how to facilitate a peaceful and consensual transition to a unified German state – a project that had been inconceivable just two days before.[18]

*

How had this Rubicon been reached, only five weeks after the grand celebrations to mark the fortieth anniversary of the East German state?

In reality the big party on 7 October was a facade, to paper over the huge and growing cracks in the communist state. As soon as Gorbachev left East Berlin for Moscow, demonstrations erupted across the city and elsewhere in the GDR and the authorities now cracked down hard. The 7th was the day of what had become a monthly protest against the May election fraud. Nevertheless, while those who had fled the country amounted to tens of thousands, the number of dissidents and those openly antagonistic to the regime was still relatively small, especially outside the big cities of Dresden, Leipzig and East Berlin. Protests and demonstrations were quite contained, involving no more than several hundred people. Formal opposition groups had only just been created since the opening of the Austro-Hungarian border: by the beginning of October some 10,000 people belonged to Neues Forum as well as Demokratie Jetzt, Demokratischer Aufbruch, SDP (SozialDemokratische Partei in der DDR) and Vereinigte Linke. These smaller groupings were mostly associated with Neues Forum. Millions of GDR citizens remained passive and hundreds of thousands were still willing to defend the state.[19]

The atmosphere in those days was tense and uncertain – the rumour mill was in overdrive about what might happen next. At the top, Erich Honecker envisaged a ‘Chinese solution’ to counter the mounting protests over the anniversary weekend (6–9 October),[20] prefigured in East Berlin when Stasi boss Erich Mielke jumped out of his bulletproof limo on the evening of 7 October screaming to police ‘Haut sie doch zusammen, die Schweine!’ (‘Club those pigs into submission!’).[21] That night in and around Prenzlauer Berg near the Gethsemane church, police officers, plain-clothes security forces and volunteer militia attacked some 6,000 demonstrators who shouted ‘Freedom’, ‘No violence’ and ‘We want to stay’, as well as bystanders, with dogs and water cannons – beating and kicking peaceful citizens and throwing hundreds into jail. Women and girls were stripped naked; people were not allowed to use the toilets and told to piss or shit in their pants. Those who asked where they would be taken were told: ‘Auf eine Müllkippe’ (‘To the landfill’).[22]

Unlike similar scenes in other East German cities, where foreign journalists were banned, the images from East Berlin that weekend soon went around the world. And when those arrested were released and talked to the press, what they told the cameras about merciless brutality by the riot police and abuse at the hands of the Stasi interrogators was both really shocking and also entirely believable. Because many of them were simply ordinary citizens, some even SED members, not militant protestors or hardcore dissidents.[23]

Matters came to a head on Monday 9 October in Leipzig, which had been the epicentre of people-protest for the past few weeks. In fact the Monday night demo there had become a weekly feature since the first gathering by a few hundred in early September, spilling out spontaneously – as numbers grew exponentially – from the evening prayers for peace (Friedensgebet) in the Nikolaikirche in the city centre to a big rally along the inner ring road. On the night of 25 September, the fourth such occasion, 5,000 people had come together; a week later there were already 15,000, calling for ‘Demokratie – jetzt oder nie’ (‘Democracy – now or never’), and ‘Freiheit, Gleichheit, Brüderlichkeit’ (‘Freedom, equality, fraternity’). On the march, they chanted defiantly ‘Wir bleiben hier’ (‘We stay here’), as opposed to the earlier ‘Wir wollen raus’ (‘We want out’), while demanding ‘Erich laß die Faxen sein, laß die Perestroika rein’ (‘Erich [Honecker] stop fooling around, let the perestroika in’). Each week, Leipzigers became more daring in their activities and more vehement in their demands.[24]

The 9th of October was expected to be the largest ever protest – facing off against the regime’s full display of force. With this in mind, the Leipzig opposition groups and churches had disseminated appeals for prudence and non-violence. The world-renowned conductor Kurt Masur of the Gewandhaus orchestra, together with two other local celebrities, enlisted the support of three leading SED functionaries of the city government, and issued a public call for peaceful action: ‘We all need free dialogue and exchanges of views about further development of socialism in our country.’ What’s more, they argued, dialogue should not only be conducted in Leipzig but also with the government in East Berlin. This so-called ‘Appeal of the Six’ was read aloud, as well as being broadcast via loudspeakers across the city during the evening church vigils.[25]

Honecker, for his part, was determined to make an example of Leipzig. The state media replayed footage of Tiananmen and endlessly repeated the government’s solidarity with their comrades in Beijing.[26] When Honecker met Yao Yilin, China’s deputy premier, on the morning of the 9th, the two men announced that there was ‘evidence of a particularly anti-socialist action by imperialist class opponents with the aim of reversing socialist development. In this respect there is a fundamental lesson to be learned from the counter-revolutionary unrest in Beijing and the present campaign’ in East Germany. Honecker himself was positively bombastic: ‘Any attempt by imperialism to destabilise socialist construction or slander its achievements is now and in the future nothing more than Don Quixote’s futile running against the steadily turning sails of a windmill.’[27]

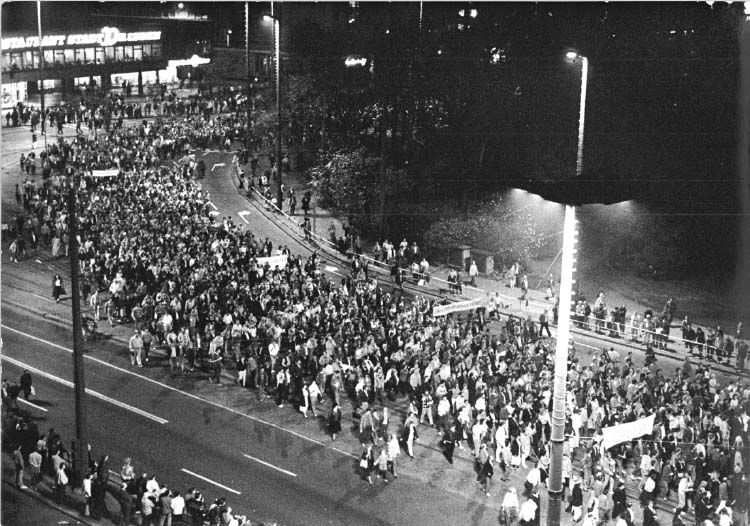

As darkness fell that evening, 9 October, with memories fresh of horrors from Berlin, many expected a total bloodbath in Leipzig. Honecker had pontificated that riots should be ‘choked off in advance’. Some 1,500 soldiers, 3,000 police and 600 paramilitary backed by hundreds of Stasi agents were ready. ‘It is either them or us,’ police were told by their superiors. ‘Fight them with no compromises,’ the interior minister ordered. The army had been given live ammunition and gas masks; the Stasi were briefed by Mielke in person; and paramilitaries and police were also called up in readiness.[28] Around 6 p.m., after prayers at the Nikolaikirche and neighbouring churches, the crowd struggled out into the streets. With more people joining the march all the time, an estimated 70,000 slowly pushed their way out onto the ring road.[29]

Marching for democracy on the Leipziger Innenstadtring

Yet the dreaded confrontation never took place. The local party was unwilling to make a move without detailed instructions from the leadership in East Berlin. The army and police were not prepared for the size of the crowd, double what they had expected. Above all, Honecker’s word was no longer law. An intense power struggle was now under way in East Berlin. Egon Krenz – twenty-five years Honecker’s junior – had been plotting a coup for some time. But, despite his recent ‘fraternal’ visit to Beijing, he did not wish to be saddled by Honecker with the opprobrium of a Tiananmen solution at home, because that would stain his own hands with German blood while allowing the elderly leader to blame him for the violence. This left the party paralysed between hardliners, ditherers and reformers. And, with no clear word that night from Berlin, the local party chief did a volte-face. Heeding the Appeal of the Six, he ordered his men to act only in self-defence. Meanwhile, the Kremlin had issued a directive to General Boris Snetkov, commander of the Western Group of Soviet Forces with his HQ in Wünsdorf near Berlin, not to intervene in East German events. The Red Army troops on East German soil were to stay in their garrisons.

So the ‘Chinese card’ was never played. Not because of a deliberate decision by the SED at the top, growing out of a change of heart, but because of the distinct absence of any decision. Time passed. The masses kept marching. There was no violence. The repressive state apparatus that Mielke had pulled together was not confronted with fearsome ‘enemies of the state’ or anarchic ‘rowdies’ but by well-disciplined ordinary citizens bearing candles and speaking the language of non-violence. What they wanted was recognition by the governing party of their legitimate quest for basic freedoms and political reform: their slogan was ‘Wir sind das Volk’ (‘We are the people’).[30]

New facts on the ground had been created. And a new demonstration culture had emerged – spilling out from the church vigils into the squares and the streets. The regime’s loss of nerve that night dispelled the omnipresent climate of fear. This would change the face of the GDR. The civil rights activists and the mass of protestors were beginning to merge.

It was a huge victory for the peaceful demonstrators and an epic defeat for the regime. ‘Die Lage ist so beschissen, wie sie noch nie in der SED war’ (‘The situation is so shitty, like it never was in the SED’), summed up one Politburo member on 17 October.[31] Next day Honecker resigned – officially on health grounds – and Krenz took over as party boss.[32] But that did not improve the public mood: the people interpreted the power transfer as the result of their pressure from below rather than as the outcome of party machinations and manoeuvrings going on ever since Honecker was taken seriously ill during the Warsaw Pact meeting in Bucharest in July.[33]

Egon Krenz at the Volkskammer as the New Party Secretary of the SED in East Berlin

Krenz promised the Party Central Committee on 18 October that he would initiate a ‘turn’ (Wende). He committed himself to open ‘dialogue’ with the opposition on two conditions: first, ‘to continue building up socialism in the GDR … without giving up any of our common achievements’ and second, to preserve East Germany as a ‘sovereign state’. As a result, Krenz’s Wende amounted to little more than a rhetorical tweak of the party’s standard dogma. And, in similar vein, the personnel changes he made among the leadership were largely cosmetic. There was, in short, little genuine ‘renewal’ in the offing: clearly Wende did not mean Umbruch (rupture and radical change).[34]

Not only did Krenz’s accession to power leave more reformist elements in the SED frustrated; worse, he personally appeared clueless in judging the true nature of the public mood. After his election to the post of SED general secretary, he asked the Protestant church leaders when ‘those demonstrations finally would come to end’. After all, continued Krenz obtusely, ‘one can’t spend every day on the streets’.[35] Little did he know.

In any case, Krenz was not a credible leader. Rumours were rife about his health and his alcohol problems. And ‘long-tooth’ Krenz, as he was nicknamed – a party hack for more than thirty years – had no plausibility as a ‘reformer’. So, rather than stabilising SED rule, his takeover actually served to fuel popular displeasure with the party and accelerated the erosion of its monopoly on power. What’s more, when the Krenz regime renounced the open use of force, that token concession only emboldened the masses to demand ever more fundamental change. They now felt they were pushing at an open door: ‘street power’ was shaking ‘the tower’.[36]

After the fall of Honecker on 18 October, anti-government protest – in the form of peace prayers, mass demonstrations and public discussions – spread right across the country. In the process various currents of criticism flowed together into a surging tide. Long-time dissidents from the churches; writers and intellectuals from the alternative left; critics of the SED from within the party; and the mass public spilling out onto the streets: all these fused in what might be called an independent public sphere. They spoke in unison for people’s sovereignty. Discontent was now open. The long spell of silence had been broken.

On 23 October in Leipzig, 300,000 participated in the Monday march around the ring road. In Schwerin on the Baltic, the ‘reliable forces’ who were meant to come out for the regime ended up in large swathes joining the parallel demo by Neues Forum. Next day the protests returned to East Berlin, whose squares had remained quiet since the brutal crackdown of 7 and 8 October. Overall, there were 145 anti-government events in the GDR in the last week of the month, and a further 210 in the first week of November. Not only were these protests growing, the demands were becoming both more diverse and also more pointed:

Die führende Rolle dem Volk (‘The leading role to the people’, 16 October)

Egon, leit Reformen ein, sonst wirst Du der nächste sein! (‘Egon, introduce reforms, or else you’ll be next!’, 23 October)

Visafrei bis Hawaii! (‘Visa-free travel to Hawaii!’, 23 October)

Demokratie statt Machtmonopol der SED (‘Democracy instead of the SED’s monopoly on power’, 30 October)

Conversely, the SED leadership appeared lost for words. Increasingly unable to win the argument, the Krenz Politburo hid behind traditional orthodoxy.[37] In particular, the party was totally unwilling to give up its constitutionally entrenched ‘leading role’ (Führungsanspruch) – which was the principal demand of all those who wanted liberalisation and democratisation.[38] To make matters worse, while seeking to reinstate its authority, the regime showed itself bewildered and helpless in the face of the GDR’s deteriorating economic situation. Discussions in the Politburo revolved around how to get consumers more tyres, more children’s anoraks, more furniture, cheaper Walkmen and how to mass-produce PCs and 1 MB chips – not the structural flaws of the economy.[39]

Only on 31 October were the stark realities finally laid bare in an official report to the Politburo by the chief planner, Gerhard Schürer, on the economic state of the GDR. The country’s productivity was 40% lower than that of the Federal Republic. The system of state planning had proved totally unfit for purpose. And the GDR was close to national insolvency. Indebtedness to the West had risen from 2 billion Valutamarks in 1970 to 49 billion in 1989.[fn1] Merely halting further indebtedness would entail a lowering of the East Germans’ living standards by 25–30% in order to service the existing debt. And any default on debt repayments would risk opening the country to an IMF diktat for a market economy under conditions of acute austerity. For the SED, this was ideologically untenable. In May, Krenz had declared that economic policy and social policy were an entwined unit, and had to be continued as such because this was the essence of socialism in the GDR. So the regime was trapped in a vicious circle: socialism depended on the Plan, and the survival of the planned economy required external credits on a scale that now made East Germany totally dependent on the capitalist West, especially the FRG.[40]

Straight after this fateful Politburo meeting, Krenz flew to Moscow for his first visit to the Kremlin as the GDR’s secretary general. There on 1 November he admitted the economic home truths to Gorbachev himself. The Soviet leader was unsympathetic. He coldly informed Krenz that the USSR had been aware of East Berlin’s predicament all along; that was why he had kept pressing Honecker for reforms. Even so, when Gorbachev heard the precise figures – Krenz said the GDR needed $4.5 billion in credits simply to pay off the interest on its debts – the Soviet leader was, for a moment, speechless – a rare occurrence. The Kremlin was in no position to help, so Gorbachev could only advise Krenz to tell his people the truth. And, for a country that had already haemorrhaged over 200,000 alienated citizens since the start of 1989, this was not a happy prospect.[41]

Afterwards, Krenz tried to put the best face on things in a seventy-minute meeting with the foreign press, presenting himself as an ‘intimate friend’ of Gorbachev and no hardliner. But the media were not convinced. When Krenz talked policy, he sounded just like Honecker, his political mentor, and he flatly rejected any talk of reunification with West Germany or the removal of the Berlin Wall. ‘This question is not on the table,’ Krenz insisted. ‘There is nothing to reunify because socialism and capitalism have never stood together on German soil.’ Krenz also put a positive spin on the mass protests. ‘Many people are out on the streets to show that they want better socialism and the renovation of society,’ he said. ‘This is a good sign, an indication that we are at a turning point.’ He added that the SED would seriously consider the demands of the protestors. The first steps, he said, would be taken at a party meeting the following week.[42]

In truth, the SED had its back to the wall. Desperate, it decided to give ground to the protestors on the question of travel restrictions – to allow an appearance of freedom. So on 1 November the GDR reopened its borders with Czechoslovakia. The result was no surprise, except perhaps to the Politburo itself. Once again the people voted with their feet: some 8,000 left their Heimat on the first day. On 3 November, Miloš Jakeš, leader of the Czech communists in Prague – having secured Krenz’s approval – formally opened Czechoslovakia’s borders to the FRG, thereby granting East Germans a legal transit route to the West. But instead of this halting the frenzied flight, the exodus only continued to grow: 23,000 East Germans arrived in the Federal Republic on the weekend of 4–5 November, and by the 8th the total number of émigrés had reached 50,000.[43]

On his return home Krenz pleaded with East Germans in a televised address. To those who thought of emigrating, he said: ‘Put trust in our policy of renewal. Your place is here. We need you.’[44] That last sentence was true: the mass flight that autumn had already caused a serious labour shortage in the economy, especially in the health sector. Hospitals and clinics had reported losing as many as 30% of their staff as doctors and nurses had succumbed to the lure of freedom, much better pay and a more high-tech work environment in the West.[45]

By this stage, few were listening to the SED leader. On 4 November half a million attended a ‘rally for change’ in East Berlin, organised by the official Union of Actors. For the first time since the fortieth-anniversary weekend, there was no police interference in the capital. Indeed, the rally – which included party officials, actors, opposition leaders, clergy, writers and various prominent figures – was broadcast live on GDR media. Speakers from the government were shouted down, with chants of ‘Krenz Xiaoping, no thanks’. Others, such as the novelist Christa Wolf, drew cheers as she announced her dislike for the party’s language of ‘change of course’. She said she preferred to talk of a ‘revolution from below’ and ‘revolutionary renewal’.

Wolf was one of thousands of opposition activists who desired a better, genuinely democratic and independent GDR. Quite definitely they did not see the Federal Republic as the ideal. They did not want their country to be gobbled up by the dominant, larger western half of Germany – in a cheap sell-out to capitalism. People like Wolf and Bärbel Bohley, the artist founder of Neues Forum, had stuck with the GDR despite all its frustrations; in their minds, running away was the soft option. So they now wanted to reap the fruit of their hard work as dissidents. They were idealists who aspired to a democratic socialism, and saw the autumn of 1989 as their chance to turn dreams into reality.

But Ingrid Stahmer, the deputy mayor of West Berlin, had a different perspective. With GDR citizens now freely flooding out of the country through its Warsaw Pact neighbours, she remarked that the Wall was soon going to become history. ‘It’s just going to be superfluous.’[46]

On Monday 6 November, close to a million people in eight cities across the GDR –some 400,000 in Leipzig and 300,000 in Dresden – marched to demand free elections and free travel. They denounced as totally inadequate the latest loosening of the travel law, published that morning in the state daily Neues Deutschland, because it limited foreign travel to thirty days. And there was a further question: how much currency would East Germans be allowed to change into Western money at home? The Ostmark was not freely convertible, and up to now East Germans had been allowed once a year to exchange just fifteen Ostmarks into DMs – about $8 at the official exchange rate – hardly enough for a meal, let alone an extended trip.[47]

So the pressure was intense when the SED Central Committee gathered on 8 November for its three-day meeting. Right at the start, the entire Politburo resigned and a new one – reduced in size from twenty-one members to eleven – was elected, to create the appearance of change. In the event, six members retained their seats, while five new ones were named. Three of Krenz’s preferred new Politburo candidates were rejected and the party gave the position of prime minister to Hans Modrow, the SED chief in Dresden – a genuine reformer. As a result, the party elite was now visibly split. What’s more, on the outside of the party headquarters, 5,000 SED members protested openly against their leaders.[48]