Полная версия

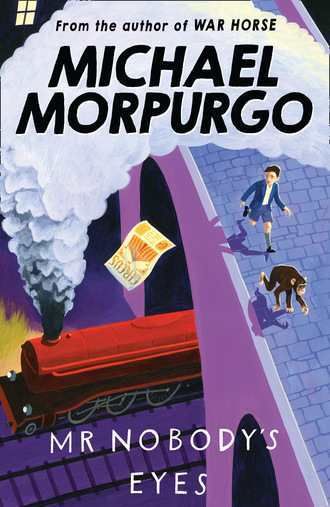

Mr Nobody's Eyes

Harry didn’t see anyone in the park, not until he reached the bench by the duck pond. Someone was sitting there, a man who seemed to be talking to the ducks perhaps, or to himself. ‘Ocky, Ocky. You come out of there, you hear me. It’s dirty. Why you always have to find the dirty places, eh?’ He spoke with a strong foreign accent and then seemed to give up English and broke into a different language altogether. Harry could see the man better now. He was dressed in a long overcoat with a fur collar and he wore a wide-brimmed black hat. When he sat back laughing on the bench he was shaking his head. Harry moved a little closer. There was something rustling in the wastepaper bin beside the bench, but he still could not make out what it was. ‘Ocky! Ocky! I think there’s somebody here,’ the man whispered, leaning forward and peering through the gloom at Harry. ‘You better come out of there, Ocky, before they see you.’ A head came up first out of the wastepaper bin, the head of a black monkey with a pink face and large pink ears that stuck out. And then the rest of it came out and scampered along the bench to sit on the man’s lap. The monkey had a cigarette packet in one hand and a newspaper in the other, and was looking directly at him. Harry wasn’t sure, but it seemed as if the little eyes that stared back at him were flashing yellow.

CHAPTER TWO

‘IS THERE SOMEBODY THERE?’ THE MAN SAID, AND Harry stepped forward. ‘Come closer.’ The man beckoned him towards the bench. ‘Don’t you worry, she won’t hurt you.’ The monkey squatted stock still on the man’s lap, lips pursed, eyes studying Harry as he approached. Harry came as close as he dared. ‘Who is it?’ the man asked.

‘Me,’ Harry said, not taking his eyes off the monkey.

‘Ah, it’s just a bambino.’ He sounded relieved. ‘I don’t see so good in this fog.’ The monkey hooted softly. ‘She want to make friends with you,’ he said, and he laughed. ‘But first I got to introduce you. You got a name?’

‘Harry Hawkins.’

‘Ocky, this is ’Arry ’Awkins. ’Arry ’Awkins, this is Ocky,’ said the man. ‘You got a little something for her, have you? She like the fruit, any kind of fruit. And sweets, she like the barley sugar, ’umbugs. Anything you got.’

Harry fished in his coat pocket. ‘Haven’t got much,’ he said, and produced the only thing he had, an old apple core from the apple his mother had given him for school only yesterday. He held it out, but too fast and the monkey screeched and shrunk back, clinging to the man’s coat.

‘’Arry, you got to be more slow,’ he said. ‘Ocky’s a chimpanzee, and chimpanzees they’re a bit like you and they’re a bit like me. They got to be sure you’re a friend before they like you. So, you got to show ’er you like ’er first. What you got there?’

‘Apple core.’

‘S’good. She like the apples. So you ’old it out, but gently now, and don’t look at her in the eyes. She don’t like it when people look at ’er in the eyes.’ Harry looked deliberately at the waste-paper bin at the end of the bench and offered the apple core, more cautiously this time. He understood then why the chimpanzee’s eyes were flashing yellow, because the wastepaper bin was too – it was the light from the Belisha beacons in the road behind him. It must have been a minute before he saw the chimpanzee move and then she only scratched herself on her shoulder with the cigarette packet. She shifted on the man’s lap and looked up into his face uttering faint whimpers.

‘Va bene, Ocky, va bene,’ said the man and he stroked the chimpanzee on the head. ‘It’s just a bambino. You take the apple, Ocky. It’s a nice one.’ A long black arm stretched out slowly towards him – it was longer than Harry expected – and snatched the apple core. She smelt it first and then bit it in half. It didn’t last long and she seemed disappointed there was no more. She searched avidly in the man’s lap and in her fur for any last bite of apple she might have missed.

‘Say thank you, Ocky,’ said the man, taking the chimpanzee’s hand and holding it out towards Harry. ‘Say “grazie bene”. She got to learn the good manners. You take ’er ’and now, ’Arry. She don’t mind, she’s your friend now.’ The hand felt like soft, cold leather, and it clung now to Harry’s bruised hand with a grip that hurt. The strength of it surprised him. Before he knew it and before he had time to feel alarmed the chimpanzee had swung herself up into the crook of his arm and settled there, an arm around his neck. She was breathing into his ear and had taken the cap off his head.

‘She’s got my cap,’ said Harry, trying to control the fear in his voice. Chuckling, the man on the bench got up and lifted her off him. He handed Harry back his cap.

‘She like to play games, don’t you Ocky?’ he said. ‘You’re a thief, a terrible thief. That’s no way to treat a friend. Now you take me ’ome, Ocky; we got to catch the bus. We got a show tonight, remember.’

‘A show?’

‘Circus, Blondini’s Circus. You never been to the circus before, ’Arry?’

‘No,’ said Harry.

‘So you come, eh? We have all the animals, it’s like Noah’s Ark. We got the horses, we got the dogs, we got the sea lions, we got the elephants and we got the clowns. We got lots of clowns. You like the clowns ’Arry? But best of all we got Ocky – she’s the big star, aren’t you Ocky?’ The chimpanzee reached out again for Harry’s cap but Harry ducked away smartly. ‘You come, eh, bambino? I, Signor Blondini, invite you personally to my circus, and you bring along your friends. You got plenty of friends, eh? I got to go now.’ He coughed and patted his chest. ‘I don’t like this fog, is bad for me. You can’t see so well in it either, but that don’t make no difference to us, does it Ocky? We got each other, eh? We find our way ’ome all right. Look, ’Arry, she’s giving you her cigarette packet. Special present from the wastepaper bin. She like you. She like everyone who is nice to her, all of the animals at the circus, too; but not the dogs. She don’t like the dogs. I don’t know why, but she go crazy when she see the dogs.’

Harry took the offered cigarette packet and then held out his hand slowly. ‘Thanks, Ocky,’ he said. Ocky reached out and touched his hand gently. Then she smelt his fingers, looking all the while into Harry’s eyes, a deep, penetrating stare that forced Harry to look away.

‘Arrivederci, bambino,’ said Signor Blondini lifting his hat. Harry saw then that his hair was silver white. He was a lot older than Harry had imagined from his voice. ‘Andiamo, Ocky, let’s go.’ Ocky took his hand and they walked away together. The chimpanzee turned to look back at him once over her shoulder and Harry saw that she had a cigarette card in her hand. Then they were swallowed in the dark of the smog. Harry looked down at the cigarette pack in his hand and opened it. It was empty.

When he got home Bill and Granny Wesley were sitting in the kitchen. He took his coat off. His tea was waiting for him on the oven, corned beef hash. He hated corned beef hash and said so.

‘Always fussy, aren’t you?’ she said. ‘Spoilt, that’s the trouble with you. There’ll be no bread-and-butter pudding until you finish it.’

‘Can I see Mum first?’ he said.

‘The doctor’s with her now, Harry,’ Bill said. ‘You can see her later.’

‘I just want to see her, that’s all.’

‘Later,’ said Bill, an edge to his voice. ‘I’m not even allowed up there now, no one is. Now eat your tea like Granny says, there’s a good lad.’ Harry looked from one to the other. Something was wrong, very wrong. For a start there was no lecture about being late. No one had noticed the tear in his trousers, and Granny Wesley hadn’t even told him to wash his hands before he ate his tea. Perhaps this was a good time to hand over the letter from Miss Hardcastle, he thought.

‘The teacher said I was to give you this,’ he said, taking it out of his pocket and pushing it across the table towards Bill.

‘What is it?’ Bill asked. There were dark, deep rings under his eyes magnified by his glasses.

‘Just a letter,’ said Harry, shrugging. Bill looked down at the envelope but didn’t seem in the slightest bit interested in opening it.

‘Eat up, eat up,’ said Granny Wesley, clapping her hands. Harry ate in silence, glancing from time to time at Bill who kept taking off his glasses and rubbing his eyes, and then at Granny Wesley who was knitting. She was always knitting, her needles clicking interminably, sometimes in unison with the tick of the kitchen clock.

He was half way through his bread and butter pudding when they heard voices from the room above them. A door shut. Footsteps were coming down the stairs.

Granny Wesley put down her knitting. ‘You stay here and you eat every last bit of it, and don’t forget your orange juice,’ she said as she opened the door into the front hall. Bill went after her, closing the door behind him. The whispering in the front hall was tantalizingly just inaudible. Harry crept to the door and put his ear to the keyhole. He could still hear no better, so he looked instead. The doctor was in his shirtsleeves and braces and was standing at the foot of the stairs. Bill was listening, head lowered, and Granny Wesley was nodding and looking at her watch. After a few moments she turned away and came back towards the kitchen door. Harry scuttled back to the table and bolted down the last of his bread-and-butter pudding. The whispering was louder now and he could just make out what they were saying. It was Bill’s voice.

‘I don’t care what you do with him . . . I want him out of here . . . for as long as possible.’ Then the door opened and Granny Wesley came in alone.

‘Can’t I see her now?’ Harry asked. ‘Is she all right?’

‘I have a nice surprise for you, young man,’ said Granny Wesley. She often called him ‘young man’ and that made Harry feel very old. ‘You and me, we’re going out,’ she said.

‘Why?’ said Harry. She’d never taken him out anywhere before.

‘Why? Because there’s something I want you to see.’

‘What?’

‘How would you like to go to the circus, young man? I saw the notice on the way back from the shops today. There’s elephants, sea lions, clowns. I haven’t been to the circus – oooh – since I don’t know when, since before the war certainly. Half past six it starts. We can be there in a quarter of an hour if we hurry.’

Harry didn’t argue. He had his coat and scarf on in a flash. Bill saw them out. ‘Don’t worry about your mother, Harry,’ he said. ‘She’ll be all right.’

Harry loved everything about buses, the race up the winding stairs to get to the top before the bus lurched forward, the ping of the bell as the conductor called out, ‘Hold very tight please’. He liked the seat at the front, so that he could hang on to the white rail in front of him and steer the bus round the corners. It was only a few stops, but to Harry’s great delight it took an age in the smog. Granny Wesley let him give the money to the bus conductor. Harry watched eagerly as he picked out the tickets, punched them and handed them over. ‘You can keep them,’ said Granny Wesley. She was being unusually kind to him, and for a moment Harry wondered why; but then they were on the pavement and caught up in a flood of people and carried along with them towards the light of a great tent with coloured lights flickering all around and music blaring from loudspeakers. Granny Wesley guided him from behind into a ringside seat and gave him a toffee apple. He tried to bite through the outside of it and failed. He couldn’t open his teeth wide enough.

He was still licking at the toffee when the lights went down, the audience hushed and the drums rolled to a crashing crescendo. A spotlight picked out a white horse, neck arched, walking out into the ring, and then behind came another, and then another, and another and another, until the ring was circled with identical horses. Harry was so close to them that he could smell them as they passed by. The sawdust from their feet flew up and landed on his coat. It was too close for comfort for Granny Wesley who held her handkerchief up to her mouth. She was to keep it there all through the performance. Then came the ringmaster, striding out into the ring, resplendent in red-spangled evening jacket and top hat, a whip in his hand. The horses came to a snorting halt and turned inwards towards him, a tail swishing right in front of Harry’s face. The loudspeaker whistled and crackled. ‘Signor Blondini is proud to present to you this evening his world famous travelling circus.’ Trumpets blared raucously and the show began.

Harry could see the ringmaster’s face. He expected him to be Signor Blondini but he wasn’t, he was sure of that. He was too tall, too young. As each act came and went he looked for Signor Blondini and Ocky, but very soon he became so absorbed in everything he saw, in the colour and the noise of it, that he forgot all about them. There were acrobats on horseback, somersaulting as they rode, jumping from horse to horse. There were sea lions tossing their footballs from tail to nose and twirling them in the air. There were elephants trooping around the ring, trunks entwined with tails, and dogs that danced on their hind legs. There were jugglers, trick cyclists, fire eaters and, in between every act, the clowns. No one on the front row escaped the soapy water. No one really wanted to – except Granny Wesley. Whenever the clowns came by with their buckets she shrank back in her seat. Harry thought she was trying to pretend she wasn’t there.

When Ocky did appear at last, Harry was taken completely by surprise. She was leading a white-faced clown into the centre of the ring. Harry nearly called out, he was so excited. The clown took a violin from under his arm and sat down on a white chair. The lights dimmed and he began to play a plaintive ringing tune that silenced at once all the buzz and the laughter in the audience. Ocky sat at his feet and picked at the sand, eating whatever it was that she found there while the clown played on. He was a sad, pathetic figure out there in the centre of the ring, somehow not in keeping with the brash, bombastic spectacle of the circus. Not for him the baggy trousers, the red braces, the outsize shoes and the grotesquely painted faces of the other clowns. He was dressed down to his red knee-length socks in a black costume covered in large yellow and red butterflies. When he played ‘The White Cliffs of Dover’ the audience joined in humming softly – some singing the words, but never too loud. And then suddenly the lights were up again and the clown-gang was back. They gathered round to mimic the butterfly clown as he played, but he took no notice. They danced idiotically, waltzing together and polka-ing together, tripping over each other; but the butterfly clown ignored them and played on. They picked up their buckets and were about to empty them on the butterfly clown, turning to the audience to ask if they should. ‘No! No!’ came the shout, and still the violin played on, a new tune now, a different tempo, faster and more rhythmic. Quite suddenly Ocky was on her feet clapping her hands. All the clowns froze where they were for just a moment, and then the butterfly clown began to sway in time to the music as he played. The clowns followed suit, no longer mocking him. They were becoming lost in the music, hypnotised by it. After a minute or two the butterfly clown stopped playing and laid the violin down on the chair behind him. He looked around the laughing audience, pointed to the still swaying clowns and put his finger to his lips to quieten the audience. Then he took several green balls out of his pockets and began to juggle with them expertly. The clowns did the same. They too dipped into their pockets and took out several green balls and they too began to juggle, throwing the balls higher and higher and then lower and lower, and in perfect time with the butterfly clown. When the butterfly clown finished, he put them back in his pocket, but he left one in his mouth. The clowns, mesmerised, did the same. It was the first and only act that Granny Wesley seemed to enjoy, and she laughed freely, a laugh Harry never knew she had in her. Whatever the butterfly clown did, the other clowns had to do, too. They could not help themselves. If he scratched his nose, they did. If he yawned, they did. If he stood on his head, they did. The audience howled for more, longing for the clown-gang to get more of their come-uppance. The butterfly clown bent down and whispered to Ocky, who ran off and fetched a bucket, a red one marked ‘OOZE’ in big letters. She dragged it back and left it at the butterfly clown’s feet. The butterfly clown bent down and whispered something to Ocky who clapped herself enthusiastically and then resumed her sitting position. All this time the clowns were duly following the butterfly clown’s every move, bending down and whispering to chimpanzees that weren’t there, and fetching their red buckets marked ‘OOZE’. And when the butterfly clown picked up the bucket Ocky had brought him, of course the clowns picked up their buckets, too. The butterfly clown, a wide grin on his face now, showed the audience that his bucket was empty. He turned round and round so that everyone could see. Everyone knew what he had in mind now and willed him on to do it. ‘Yes! Yes!’ they roared. ‘Yes! Yes!’ He didn’t need much persuasion, but he pretended he did until the audience had insisted loudly enough and long enough. Satisfied now that this was really what they wanted, he lifted the bucket up above his head and turned it upside down, and so did all the clowns around him, covering themselves in a white ooze that dribbled over their heads and down their shoulders. As the clowns wiped their faces the audience roared their approval. They stamped and they clapped, Harry as loudly as anyone. Ocky clapped her hands with everyone else, and then led the butterfly clown in a lap of triumph around the circus ring.

As she passed by, Harry called and called to her but to his great disappointment Ocky never even turned to look. Harry gazed up at the face of the butterfly clown and tried to catch his eye, but he seemed to be looking into the far distance almost as if he was in a trance. Harry waved at him but he never waved back. The man sitting next to Harry was shouting as he clapped, ‘That’s him. That’s Mr Nobody, I know it is.’

‘I beg your pardon?’ said Granny Wesley over Harry’s head. The man was shouting louder, clapping all the while and pointing.

‘Him, that clown, that’s Mr Nobody. I seen him do the very same thing before the war. Famous he is, Mr Nobody.’

‘How do you know it’s him?’ Harry asked.

‘Well you always know with the clowns, son. They all of them wear different costumes, different make-up. Like a sort of trademark. No two clowns are ever the same. It’s him, I know it is. No one else like him.’

The lap of triumph had become the grand parade, the finale. The horses came by, and the elephants, the acrobats and the dogs; and the clowns still scooping the white ooze off their faces and throwing it into the audience or at each other. In front of them all came Ocky leading Mr Nobody by the hand. They were coming past him again. ‘It’s him. I’m sure it is. That’s Mr Nobody,’ cried the man beside Harry, craning forward. ‘It is you, isn’t it, Mr Nobody?’ The butterfly clown heard, smiled and nodded, but he hardly turned his head. Then he seemed to stumble in the sawdust and clutched at the ringside to steady himself, his hand gripping the rail right in front of Harry’s seat. His hair grew only sparsely on the top of his head, but was long and bushy and red around his ears. Except for that his entire head down to his neck was chalk white. His startlingly red lips, the same colour as his hair, were painted where there were no lips, but the two black moles above and below his mouth looked real enough. As Harry looked at him their eyes met momentarily and Harry could see why he had stumbled. Mr Nobody’s eyes were full of dreams. He was like a man walking in his sleep. And then he was gone, the parade was all over, the magic was broken and they were all leaving.

At the bus stop outside there was a long queue and Peter Barker was there. ‘Smashing, wasn’t it?’ he said and Harry nodded. ‘Don’t you like your toffee apple?’ he said. Until then Harry hadn’t even realised he still had it. His hand was sticky with toffee down to his wrist. He began to lick his fingers.

‘Still hurting, is it?’ said Peter Barker.

‘What?’ said Harry, knowing quite well what he meant, but not wanting Granny Wesley to find out anything about it.

‘Your hand,’ said Peter Barker deliberately loudly.

‘What happened to your hand?’ asked Granny Wesley.

‘I fell over,’ Harry said, ‘in the playground. But it’s all right now.’ He looked darkly at Peter who was about to argue but stopped just in time to avoid getting his shin kicked.

There was a long cold wait until the right bus came. Granny Wesley stamped her feet and grumbled about the buses, and when theirs came at last she complained to the conductor that it wasn’t right to keep people waiting on a night like this and that she was in a hurry to get home. The conductor winked at Harry and said he was sorry but there wasn’t a lot he could do about the smog, and that seemed to silence Granny Wesley for a bit. She kept looking at her watch, shaking he head and tutting all the way home.

Bill met them at the door smiling broadly. ‘I’ve got a son,’ he said, and he hugged Granny Wesley, who began to cry.

‘Can I see Mum, then?’ Harry said.

‘And you’ve got a little brother, Harry,’ said Bill. ‘What do you think of that?’ Harry wanted neither a brother nor a sister, but if he had to make a choice he’d have preferred a sister.

‘Can I see her?’

‘’Course you can,’ said Bill. ‘Just for a minute or two. The doctor says we mustn’t tire her. She’s had a rough time of it you know, Harry. She had us all worried sick, your mother did.’

Harry’s mother was propped up on her pillows, her fair hair all around her, like a halo, Harry thought. She smiled weakly at Harry as he came closer. There was a wicker cradle beside the bed. Harry’s mother held out her arms to him, and kissed him.

‘Did you have a good time dear?’ she said. ‘Billy said Granny took you to the circus.’ Harry peered down at the baby in the cradle. All he could see was a bright pink, wrinkled face and one tiny clenched fist. There was some dark hair which looked a bit wet. The rest of him was hidden under the blankets. Granny Wesley was beside him now, bending over the cradle, wiping her eyes with a handkerchief. ‘Isn’t he the perfect poppet,’ she said. ‘He looks just like Bill did when he was born, just the same.’

‘What do you think of him, Harry?’ asked his mother. ‘Isn’t he the most beautiful boy you ever saw? Isn’t he?’ Harry didn’t know what to say because he certainly wasn’t beautiful, but he didn’t want to have to tell his mother that. So he said nothing.

‘We’re calling him George,’ said Bill, ‘after my father. Suits him, don’t you think?’

‘Oh that’s wonderful,’ said Granny Wesley. ‘Wonderful.’ And she cried some more.

Harry went over to the bed to sit by his mother. ‘Are you better now, Mum?’ he asked.

‘I’ll be fine dear,’ she said, and then her face filled suddenly with anxiety. ‘Oh, be careful with him!’ she cried. Granny Wesley had picked up the baby and was cradling him in her arms.

‘Oh, don’t you worry, my dear,’ she chortled, her crooked finger stroking the baby’s chin. ‘I’ve done this before, remember? I know what I’m doing. You can see the Wesley in him. Big forehead. Sign of intelligence.’

‘Please put him down, Granny,’ Harry’s mother begged, her eyes full of tears. ‘Please.’ Bill and Granny Wesley looked at each other.

‘You’re tired, dear,’ said Bill taking the baby from Granny Wesley and laying it back in the cradle. ‘You’d better go now, Harry. Kiss your mother goodnight and then off to bed with you. It’s late enough already and you’ve got school again tomorrow.’ Harry wanted to stay with his mother and he knew she would have liked that too but she would not say so. She never seemed to stand up for him these days. ‘You’d better go, dear,’ she said. ‘I’ll see you tomorrow.’

Harry lay there on his bed. No one came to say goodnight to him but someone switched off the light in the passage plunging him into the darkness. They knew he liked the light left on, they knew it. He was relieved though that his worst wishes had not come true. He hadn’t wanted the baby actually to die, just not to come, that’s all; but since the baby hadn’t died, since it had come, he wouldn’t have to mention his wicked thoughts to Father Murphy at Confession. He said his prayers lying down. He knew he shouldn’t, but it was too cold to get out of bed. He prayed for all the usual people and he included little George too because he thought he ought to. He prayed especially that night for Signor Blondini and Ocky and for Mr Nobody, the butterfly clown, but not at all for Miss Hardcastle, definitely not for Miss Hardcastle.