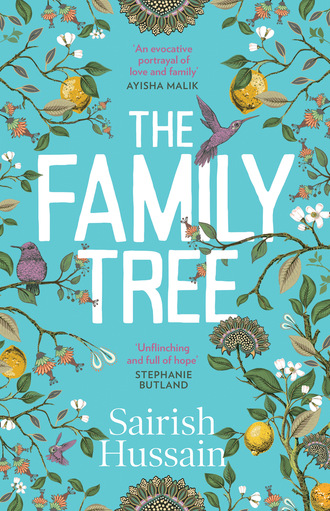

The Family Tree

SAIRISH HUSSAIN was born and brought up in Bradford, West Yorkshire. She studied English Language and Literature at the University of Huddersfield and progressed onto an MA in Creative Writing. Sairish completed her PhD in 2019 after being awarded the university’s Vice-Chancellor’s Scholarship. The Family Tree is her debut novel and she is now writing her second book.

The Family Tree

Sairish Hussain

ONE PLACE. MANY STORIES

Copyright

An imprint of HarperCollins Publishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

First published in Great Britain by HQ in 2020

Copyright © Sairish Hussain 2020

Sairish Hussain asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Ebook Edition © February 2020 ISBN: 9780008297473

Note to Readers

This ebook contains the following accessibility features which, if supported by your device, can be accessed via your ereader/accessibility settings:

Change of font size and line height

Change of background and font colours

Change of font

Change justification

Text to speech

Page numbers taken from the following print edition: ISBN 9780008297459

For my grandmothers,

Anwar Jan and Riaz Begum.

Thank you for your warmth and wisdom.

Contents

Cover

About the Author

Title Page

Copyright

Note to Readers

Dedication

Part One

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

Seven

Eight

Nine

Ten

Part Two

Eleven

Twelve

Thirteen

Fourteen

Fifteen

Sixteen

Seventeen

Eighteen

Nineteen

Twenty

Twenty-One

Twenty-Two

Twenty-Three

Part Three

Twenty-Four

Twenty-Five

Twenty-Six

Twenty-Seven

Twenty-Eight

Twenty-Nine

Thirty

Thirty-One

Thirty-Two

Thirty-Three

Thirty-Four

Thirty-Five

Thirty-Six

Thirty-Seven

Thirty-Eight

Thirty-Nine

Forty

Forty-One

Forty-Two

Forty-Three

Forty-Four

Forty-Five

Forty-Six

Forty-Seven

Forty-Eight

Forty-Nine

Fifty

Fifty-One

Fifty-Two

Acknowledgements

About the Publisher

One

February 1993

He clutched the tiny bundle in his trembling arms, rocking gently back and forth, careful not to make a sound. The streetlamps were glowing outside. He could see the dull orange light burning through the misted window. It was 4 a.m. and Amjad wondered if he would get any sleep now. He doubted it. Sleep provided a merciful cover and it had been blown only a few moments before. The sound had travelled ruthlessly down the hallway, determined to trouble him. He considered turning over on the couch and placing something over his ears. His arm throbbed as he eased it from under his weight, and his fingers twitched longingly as he contemplated reaching out for a cushion.

Minutes later, Amjad plodded up the stairs. He dragged his feet, step by step, one arm using the banister to pull himself up, the other still throbbing and limp by his side. He paused for a moment, balling up his fist in determination. He needed all the strength he could muster, all the resolve in the world to reach the top of those damn stairs.

Five little fingers were now wrapped tightly around his pinky. His daughter’s face rested peacefully against him, her tiny chest rising and falling. Amjad had wrapped her up in his wife’s shawl and tried not to think of the disgraceful thoughts he had entertained just moments before. The ones where he’d wanted to block out Zahra’s frantic wails with a beige corduroy cushion.

Amjad held Zahra close. Even then, amidst all the pain, he could not help but smile as he looked at her. He had managed to soothe his newborn baby, despite desperately needing consolation himself. It was the first of a series of ‘moments’. For the next few weeks, Amjad would find himself comparing his two lives. The previous one, in which he could simply call out and his wife, Neelam, would come rushing into the room to assist. And this new one, where his voice would reverberate against the dark walls and disappear into nothing. They would never stand together over Zahra’s cot and exchange tired smiles, fingers interlocked as Neelam’s head rested on his shoulder. They would never shush each other as they eventually tiptoed back to bed, Neelam telling Amjad off for stepping on a creaking floorboard.

Amjad wiped his eyes. It had all changed. The mud under his fingernails proved that. Only yesterday he had thrown the earth into his wife’s grave and cried silently at the mosque beside her body. Now it was just Amjad. Amjad, rocking back and forth in a darkened room, clinging on to Zahra.

She would never know her mother. Her little face would never be cupped by Neelam’s hands. The tips of their noses would never touch. The injustice of it all crushed him and Amjad wanted to fight against it. Was there no one he could protest to or demand an explanation from? No complaints form, no senior institution he could persuade to overturn their decision, to let his wife live?

Amjad thought he saw a pair of eyes peeking through the bedroom door. It creaked open and ten-year-old Saahil teetered into the room. His long, uncombed hair shrouded his tiny face and his big, doleful eyes looked to Amjad, desperately.

‘Come here,’ Amjad whispered, arm outstretched.

Saahil walked closer and leaned in to his father. His shaky little hand gently stroked Zahra’s head. Amjad felt his heart break.

‘My beautiful little boy,’ he said as he enveloped his son. They all huddled together for some time. Zahra, wrapped in the silky smoothness of her mother’s shawl, and sleeping soundly against her father’s chest. Saahil, small and as fragile as a baby deer, struggling to take his first steps in a new world, a world without his mother. And Amjad, holding them all together. He must stop feeling sorry for himself, he thought. He was determined to protect his children from anything. Pain would have no place in his household. He would fling it out the door at its first appearance.

The dull orange glow shed light on the family’s silhouette in the darkened room. A raindrop slid down the window.

Two

February 1994

The nagging started a year after Neelam’s passing. As they approached the dreaded first anniversary, Amjad’s mother seemed to grow in confidence.

‘You need to marry again,’ she said, peering at him expectantly through her jam-jar glasses. ‘Are you listening to me?’

Amjad rolled his eyes. ‘Do you want to eat saag aloo tonight, Ammi?’ he asked, jumping up from the sofa and heading towards the kitchen.

Food was his second-best tactic at diverting the conversation of marriage. Running out of the room was the first. On this occasion, despite combining them both, Amjad knew he wasn’t going to get out of it so easily. His mother’s voice followed him into the kitchen. It grew shrill and spiky, almost as if it had developed fingers and clipped him around the ears.

‘Don’t change the subject,’ she snapped.

Amjad flinched at the sound. He knelt down and opened his cupboards. His scowl turned into a beam as he admired his fully stocked shelves. As soon as Ammi announced that she would be visiting, Amjad had rushed out to replenish the groceries. He didn’t want a repeat of what had happened on her last visit. She’d opened the cupboards to find nothing but baby food, sweet corn and an out-of-date tin of tuna. As expected, a rant had ensued.

This time, the kitchen was well stocked with fresh ingredients. Amjad reached in and sliced open a brand-new sack of potatoes. He eyed some tinned spinach but remembered that he’d bought a fresh bag for tonight’s supper. Ammi wouldn’t be impressed with anything that came out of a tin. He placed both items on the worktop and realised that Ammi was still talking.

‘The kids need a mother,’ she called out. ‘You can’t do it all by yourself.’

Amjad sighed and realised that Ammi wasn’t going to drop it. Reluctantly, he headed back towards the lounge and peered around the door. He saw his mother’s slightly magnified eyes focus on him through her glasses. She sat up straight, raring to go. Amjad took a seat opposite and watched her adjust the loosely draped scarf around her neck impatiently. He braced himself.

A year after Neelam’s passing was, according to Ammi, a reasonable timeframe in which to mention marriage. It was her way of being tactful. After all, it was the last first of that year. Each hurdle had been planned by Amjad to reduce the trauma for them all. He’d fretted over what to do for Saahil’s first birthday without his mum. An answer came in the form of Ehsan, Saahil’s best friend at school. They’d spent the day playing together at a trampoline park before ending with a sleepover at Ehsan’s house. It was for the best, to keep Saahil away from home. A home without Neelam. Amjad was quite sure that Saahil hadn’t completely forgotten about his mother’s absence on his birthday. He was, in fact, just better at surviving. Children always were, everyone told Amjad.

Eid was another major hurdle. As the day approached, Amjad just wanted to be as far away as possible. An empty home on Eid would feel like a betrayal to Neelam, but the smell of her cooking would not fill the rooms. There would be no samosas crackling as they entered the hot oil. Or lamb biryani steaming when removed from the oven. Neelam’s soft voice would not nag Amjad to smarten up his clothes for when the guests arrived. Or scold Saahil for making the living room untidy again. How, then, could Amjad spend Eid there?

Ammi seemed to offer a solution by inviting them to her house. She called Javid, Amjad’s brother, and ordered him to drive up from Birmingham to spend the day with them. Amjad, however, had received another invitation from one of his closest friends, Harun, who also happened to be Ehsan’s father. Despite Eid being a non-negotiable day of the year to spend with family, Amjad did the unthinkable and rejected Ammi’s offer. As expected, she hit the roof, scolding him for wanting to spend Eid with non-relatives. But there was a generosity in Harun’s invitation that Amjad was grateful for. It offered him exactly what he needed at the time: a complete and utter change. He wanted new conversation that didn’t involve pity for himself and his children. He wanted to eat food that was cooked by Harun’s wife, Meena, knowing it would taste different. He wanted Saahil to have an amazing time playing with his best friend. True, there wasn’t much to Eid except for excessive amounts of eating and tea drinking, but Amjad knew that if he had taken the children to Ammi’s house, they would all be searching for the only person missing in the sea of faces.

Every landmark Amjad came through felt like an achievement. But the anniversary of his wife’s death and daughter’s birth loomed over him as it drew nearer. He needed to cross over and guide his children through this final push. Almost like another birth, there was trauma, pain, a determination to squeeze through, and a great gasp of air. They would all come out on the other side, hurting but still alive.

‘Anyway, what about you?’ Ammi’s voice rang in his ears. ‘Do you want to end up all alone? You need someone you can grow old with.’

Amjad sighed. ‘I’m not going to marry a stranger from Pakistan and bring her over here to clean the house and look after my kids. They’ve got me and you, they don’t need anyone else.’

‘Well, I’m not going to live forever!’ Ammi screeched. ‘I’m an old woman.’

‘You’re only fifty-nine,’ Amjad laughed.

‘You don’t listen to anything I say,’ she said, ignoring him. ‘You won’t even let me move in and help you out.’

Amjad smiled patiently. He watched his mother peel pomegranates for Saahil who stuffed the seeds into his mouth quicker than they appeared on the plate. Every now and then, her henna-tipped fingers ran over his face affectionately. Amjad was pleased with how the bond between grandmother and grandson had strengthened over the past year. But he still needed to stand his ground on this subject.

‘Look, Ammi,’ he said, slightly tired of having to explain himself yet another time. ‘You’ve lived in the same house since you came to this country. You’ve got friends and neighbours, your own little community. It would be difficult for you to change homes after thirty years. Plus, I don’t want my house turning into a royal souvenir shop,’ he said, with a mischievous glint in his eye.

Ammi had always been a staunch royalist. Royal memorabilia littered her home, most of which were gifts bought for her by Amjad’s father. Teapots, cups and saucers, plates, bowls, brooches, card holders for her bus pass, keyrings and even books she couldn’t read a word of. You name it, Ammi had it.

‘And anyway,’ Amjad continued after seeing the royal joke hadn’t gone down too well with his mother. ‘It’s good to stay independent for as long as you can.’

He really didn’t need another guilt trip for not letting his mother move in with him. As the eldest son, it was considered his duty to look after her in this way. Since his father had died a few years ago, Ammi was constantly reminding him of how old she was. It was a cunning little tactic that Amjad believed was quite popular amongst Asian parents. He’d recently exchanged notes with some of his friends to find out what their ageing mothers and fathers got up to. They were all familiar with the older generation’s mindset of being at death’s door at the age of fifty-five, and needing looking after.

‘Ah yes,’ Ammi retorted. ‘And I suppose when I can no longer stay independent you will chuck me into a nursing home like goray do away with their parents.’

‘Well, like I said, you’re fifty-nine. No care home would have you!’

Ammi glared at him. Amjad suppressed a smirk.

‘I really don’t know what the problem is,’ he said, deciding enough was enough. ‘You’re here quite a lot anyway. You stay overnight. I pick you up and drop you off whenever you want.’

Ammi argued back and although Amjad didn’t say it, the constant pestering was the main reason he didn’t want his mother living with them. Whenever she came over, she would settle herself down in her favourite spot, all fluffed up like a hen ready to roost. Her head darted with precision in all directions, and her beady eyes remained forever watchful. Maybe he was imagining things, but Amjad felt as though she was always waiting for some slight error to be made, evidence that he needed to marry again. After all, a woman would not put ketchup in the curry instead of using fresh tomatoes as Amjad often did. Or tie Zahra’s nappy the wrong way around. Although Amjad knew she meant well, the last thing he needed was to be pecked to death over silly mistakes. He would sigh with relief when he dropped the old woman off on her own doorstep, guilt stabbing at him as he drove around the corner and out of sight. Especially as he remembered how much he had relied on her during the months following Neelam’s death.

Had it not been for his mother, Amjad doubted he would have survived the shock. He knew his children craved a nurturing female presence, and only Ammi was able to provide that. Her warmth revitalised them whenever she entered the house. She swept through each room, dusting things down, lighting fires and throwing open curtains. Life returned to the home as Ammi’s voice rang through it. The children laughed and played. When Ammi took charge, Amjad would shuffle off into a corner, glad he no longer had to be the strong one.

And of course, there was Harun and Meena. Such was their friendship that Saahil had been with them the night Neelam went into labour. Harun’s cheery voice had answered Amjad’s call from the hospital. The expectation of good news diminished the moment Amjad told Harun that his wife had haemorrhaged after the delivery. Amjad could still remember the stuttering disbelief in his friend’s voice. He could still hear the muffled outburst of grief in Meena from the other end of the phone. They had reassured him that they would take care of Saahil for as long as he needed. And their support did not stop there.

As Amjad adapted to his new life without Neelam, he realised that he needed help with everything. If Ammi wasn’t there, then Meena was always on hand to teach him how to look after a newborn. She showed him the proper way to bathe an infant and how to mix the baby formula correctly. She was the first person Amjad would call late at night when Zahra cried and wouldn’t settle. Meena shooed Harun away to carry out other jobs. Amjad remembered staggering down the stairs on those first painful mornings without his wife. He’d find supermarket bags full of food on his kitchen worktop. He knew it was his friend, Harun, who had left them there during his daily school run with Saahil and Ehsan. Meena was always available to babysit the children. Harun was there in other ways. Amjad could call him up and jump into his taxi at any time. They would go for long, quiet drives. It was just what Amjad needed to clear his head. Harun never refused him or asked why. He just drove in silence.

Slowly but surely, Amjad was able to lift his eyes from the ground. Ammi, Harun and Meena had got him through the last twelve months and now, he had developed a pretty decent system. It took time, with many accidents and failures along the way. Saahil had adjusted to his new role and was always on stand-by whenever Amjad attended to Zahra. Nappies, baby bottle, dummy, he ran to fetch whatever Amjad ordered. When Zahra began crawling, Saahil followed her around the room as she scuttled between table legs and put random objects into her mouth. He stood patiently against the kitchen door as Amjad was known to forget about the shuffling baby and fling it open from the other side. Now that Zahra was trying to walk, Saahil would distract her as his father ironed his school uniform and tidied the house.

Making dinner was also a joint effort. Unlike Neelam’s finely chopped onions and selected spices added to the curry in a timed manner, Amjad just threw it all in and hoped for the best. He’d never really cooked before in his life and had initially turned for help to Ammi who was delighted with an opportunity to boss him around.

‘Remember to brown the onions!’ she’d shout at him from the lounge.

Fifteen minutes later, Amjad would empty fragments of charred onion into the dustbin. How brown were they supposed to be? Ammi just had a knack for things. He didn’t. He’d quickly hide the burnt pan in a cupboard and pull out another one before Ammi waddled into the kitchen to inspect his progress. He preferred learning how to cook at Ammi’s house. She would eventually get impatient and send him off to watch TV. She’d rustle something up in no time, and fill some Tupperware for him to take home. On these days, Saahil would eagerly run down to the roti shop a few streets away and buy four chapattis for a pound. Of course, the days Amjad could not muster the energy to cook, he would get some fish and chips for dinner or simply reach out for the faithful can of Heinz beans, always available to throw over some toast.

No shop-bought rotis were allowed in the home if Ammi was around. She would knead the dough and roll out the chapattis herself. Amjad would tear off a small piece and give it to Zahra to nibble on. It was, however, another opportunity for Ammi to check his cupboards, which almost never met her standards.

‘No ginger!’ she’d remark. ‘How can you make curry with no ginger?’

Twelve months later, though, this was becoming Ammi’s biggest weapon to use against him. The lack of garlic or ginger only suggested one thing:

‘See, this is why you need a woman in the house,’ she’d squawk. ‘And if not me, then it’s time you got married again!’ Amjad would block his ears.

‘So,’ he said, glancing at Ammi with the hope that the conversation of marriage was over. ‘Is saag aloo okay then?’

Ammi sniffed and began muttering under her breath. Amjad grinned and went back to the kitchen, as if to get started. Instead, he stood by the sink and stared out of the window. After taking a year out from work, tomorrow Amjad would return to his job as a warehouse operative on a part-time basis. He would drop Saahil off to school and Zahra off at Ammi’s in the mornings and be home by noon. His return to work felt like definitive proof that his family were now more than just managing. Saahil no longer stared into the distance, still and despondent. He was actually excited to start secondary school. The offer letters notifying them of which school he’d been placed in would be arriving in the post in the coming weeks. And Zahra was beautiful. She was taking her first steps and saying words other than ‘dada’. Amjad was still going to be their father, but also a man who worked and had his own independence. A year later, and Amjad realised that there were other things to think about now.

Neelam was still a part of their lives, but her love manifested itself in other ways. The shawl she had grabbed and wrapped around her shoulders on the night of Zahra’s birth remained a constant presence in their daughter’s life. It was the last item of clothing that Neelam had snatched from the bed, just as the contractions grew in strength. The last source of comfort his wife had felt, the last bit of fabric her fingers had caressed. It was the same shawl that Amjad wrapped his newborn inside, on the night after Neelam’s burial. It was a silk-blend pashmina shawl sent to Neelam from her mother in Pakistan. Against a teal blue backdrop, a border of mustard yellow florals snaked their way around the fabric. The shawl was finished with a heavy yellow fringe on either side. Amjad was determined to keep it as close to Zahra as possible, almost as though it was a gateway to Neelam’s love. Now, she wouldn’t settle without it.