полная версия

полная версияThirty Years' View (Vol. I of 2)

"Let no one say the bank will not avail itself of its capacity to amass real estate. The fact is, it has already done so. I know towns, yea, cities, and could name them, if it might not seem invidious from this elevated theatre to make a public reference to their misfortunes, in which this bank already appears as a dominant and engrossing proprietor. I have been in places where the answers to inquiries for the owners of the most valuable tenements, would remind you of the answers given by the Egyptians to similar questions from the French officers, on their march to Cairo. You recollect, no doubt, sir, the dialogue to which I allude: 'Who owns that palace?' 'The Mameluke;' 'Who this country house?' 'The Mameluke;' 'These gardens?' 'The Mameluke;' 'That field covered with rice?' 'The Mameluke.' – And thus have I been answered, in the towns and cities referred to, with the single exception of the name of the Bank of the United States substituted for that of the military scourge of Egypt. If this is done under the first charter, what may not be expected under the second? If this is done while the bank is on its best behavior, what may she not do when freed from all restraint and delivered up to the boundless cupidity and remorseless exactions of a moneyed corporation?

"6. To deal in pawns, merchandise, and bills of exchange. I hope the Senate will not require me to read dry passages from the charter to prove what I say. I know I speak a thing nearly incredible when I allege that this bank, in addition to all its other attributes, is an incorporated company of pawnbrokers! The allegation staggers belief, but a reference to the charter will dispel incredulity. The charter, in the first part, forbids a traffic in merchandise; in the after part, permits it. For truly this instrument seems to have been framed upon the principles of contraries; one principle making limitations, and the other following after with provisos to undo them. Thus is it with lands, as I have just shown; thus is it with merchandise, as I now show. The bank is forbidden to deal in merchandise – proviso, unless in the case of goods pledged for money lent, and not redeemed to the day; and, proviso, again, unless for goods which shall be the proceeds of its lands. With the help of these two provisos, it is clear that the limitation is undone; it is clear that the bank is at liberty to act the pawnbroker and merchant, to any extent that it pleases. It may say to all the merchants who want loans, Pledge your stores, gentlemen! They must do it, or do worse; and, if any accident prevents redemption on the day, the pawn is forfeited, and the bank takes possession. On the other hand, it may lay out its rents for goods; it may sell its real estate, now worth three millions of dollars, for goods. Thus the bank is an incorporated company of pawnbrokers and merchants, as well as an incorporation of landlords and land-speculators; and this derogatory privilege, like the others, is copied from the old Bank of England charter of 1694. Bills of exchange are also subjected to the traffic of this bank. It is a traffic unconnected with the trade of banking, dangerous for a great bank to hold, and now operating most injuriously in the South and West. It is the process which drains these quarters of the Union of their gold and silver, and stifles the growth of a fair commerce in the products of the country. The merchants, to make remittances, buy bills of exchange from the branch banks, instead of buying produce from the farmers. The bills are paid for in gold and silver; and, eventually, the gold and silver are sent to the mother bank, or to the branches in the Eastern cities, either to meet these bills, or to replenish their coffers, and to furnish vast loans to favorite States or individuals. The bills sell cheap, say a fraction of one per cent.; they are, therefore, a good remittance to the merchant. To the bank the operation is doubly good; for even the half of one per cent. on bills of exchange is a great profit to the institution which monopolizes that business, while the collection and delivery to the branches of all the hard money in the country is a still more considerable advantage. Under this system, the best of the Western banks – I do not speak of those which had no foundations, and sunk under the weight of neighborhood opinion, but those which deserved favor and confidence – sunk ten years ago. Under this system, the entire West is now undergoing a silent, general, and invisible drain of its hard money; and, if not quickly arrested, these States will soon be, so far as the precious metals are concerned, no more than the empty skin of an immolated victim.

"7. To establish branches in the different States without their consent, and in defiance of their resistance. No one can deny the degrading and injurious tendency of this privilege. It derogates from the sovereignty of a State; tramples upon her laws; injures her revenue and commerce; lays open her government to the attacks of centralism; impairs the property of her citizens; and fastens a vampire on her bosom to suck out her gold and silver. 1. It derogates from her sovereignty, because the central institution may impose its intrusive branches upon the State without her consent, and in defiance of her resistance. This has already been done. The State of Alabama, but four years ago, by a resolve of her legislature, remonstrated against the intrusion of a branch upon her. She protested against the favor. Was the will of the State respected? On the contrary, was not a branch instantaneously forced upon her, as if, by the suddenness of the action, to make a striking and conspicuous display of the omnipotence of the bank, and the nullity of the State? 2. It tramples upon her laws; because, according to the decision of the Supreme Court, the bank and all its branches are wholly independent of State legislation; and it tramples on them again, because it authorizes foreigners to hold lands and tenements in every State, contrary to the laws of many of them; and because it admits of the mortmain tenure, which is condemned by all the republican States in the Union. 3. It injures her revenue, because the bank stock, under the decision of the Supreme Court, is not liable to taxation. And thus, foreigners, and non-resident Americans, who monopolize the money of the State, who hold its best lands and town lots, who meddle in its elections, and suck out its gold and silver, and perform no military duty, are exempted from paying taxes, in proportion to their wealth, for the support of the State whose laws they trample upon, and whose benefits they usurp. 4. It subjects the State to the dangerous manœuvres and intrigues of centralism, by means of the tenants, debtors, bank officers, and bank money, which the central directory retain in the State, and may embody and direct against it in its elections, and in its legislative and judicial proceedings. 5. It tends to impair the property of the citizens, and, in some instances, that of the States, by destroying the State banks in which they have invested their money. 6. It is injurious to the commerce of the States (I speak of the Western States), by substituting a trade in bills of exchange, for a trade in the products of the country. 7. It fastens a vampire on the bosom of the State, to suck away its gold and silver, and to co-operate with the course of trade, of federal legislation, and of exchange, in draining the South and West of all their hard money. The Southern States, with their thirty millions of annual exports in cotton, rice, and tobacco, and the Western States, with their twelve millions of provisions and tobacco exported from New Orleans, and five millions consumed in the South, and on the lower Mississippi, – that is to say, with three fifths of the marketable productions of the Union, are not able to sustain thirty specie paying banks; while the minority of the States north of the Potomac, without any of the great staples for export, have above four hundred of such banks. These States, without rice, without cotton, without tobacco, without sugar, and with less flour and provisions, to export, are saturated with gold and silver; while the Southern and Western States, with all the real sources of wealth, are in a state of the utmost destitution. For this calamitous reversal of the natural order of things, the Bank of the United States stands forth pre-eminently culpable. Yes, it is pre-eminently culpable! and a statement in the 'National Intelligencer' of this morning (a paper which would overstate no fact to the prejudice of the bank), cites and proclaims the fact which proves this culpability. It dwells, and exults, on the quantity of gold and silver in the vaults of the United States Bank. It declares that institution to be 'overburdened' with gold and silver; and well may it be so overburdened, since it has lifted the load entirely from the South and West. It calls these metals 'a drug' in the hands of the bank; that is to say, an article for which no purchaser can be found. Let this 'drug,' like the treasures of the dethroned Dey of Algiers, be released from the dominion of its keeper; let a part go back to the South and West, and the bank will no longer complain of repletion, nor they of depletion.

"8. Exemption of the stockholders from individual liability on the failure of the bank. This privilege derogates from the common law, is contrary to the principle of partnerships, and injurious to the rights of the community. It is a peculiar privilege granted by law to these corporators, and exempting them from liability, except in their corporate capacity, and to the amount of the assets of the corporation. Unhappily these assets are never assez, that is to say, enough, when occasion comes for recurring to them. When a bank fails, its assets are always less than its debts; so that responsibility fails the instant that liability accrues. Let no one say that the bank of the United States is too great to fail. One greater than it, and its prototype, has failed, and that in our own day, and for twenty years at a time: the Bank of England failed in 1797, and the Bank of the United States was on the point of failing in 1819. The same cause, namely, stockjobbing and overtrading, carried both to the brink of destruction; the same means saved both, namely, the name, the credit, and the helping hand of the governments which protected them. Yes, the Bank of the United States may fail; and its stockholders live in splendor upon the princely estates acquired with its notes, while the industrious classes, who hold these notes, will be unable to receive a shilling for them. This is unjust. It is a vice in the charter. The true principle in banking requires each stockholder to be liable to the amount of his shares; and subjects him to the summary action of every holder on the failure of the institution, till he has paid up the amount of his subscription. This is the true principle. It has prevailed in Scotland for the last century, and no such thing as a broken bank has been known there in all that time.

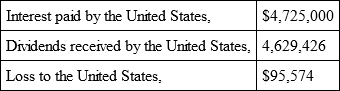

"9. To have the United States for a partner. Sir, there is one consequence, one result of all partnerships between a government and individuals, which should of itself, and in a mere mercantile point of view, condemn this association on the part of the federal government. It is the principle which puts the strong partner forward to bear the burden whenever the concern is in danger. The weaker members flock to the strong partner at the approach of the storm, and the necessity of venturing more to save what he has already staked, leaves him no alternative. He becomes the Atlas of the firm, and bears all upon his own shoulders. This is the principle: what is the fact? Why, that the United States has already been compelled to sustain the federal bank; to prop it with her revenues and its credit in the trials and crisis of its early administration. I pass over other instances of the damage suffered by the United States on account of this partnership; the immense standing deposits for which we receive no compensation; the loan of five millions of our own money, for which we have paid a million and a half in interest; the five per cent. stock note, on which we have paid our partners four million seven hundred and twenty-five thousand dollars in interest; the loss of ten millions on the three per cent. stock, and the ridiculous catastrophe of the miserable bonus, which has been paid to us with a fraction of our own money: I pass over all this, and come to the point of a direct loss, as a partner, in the dividends upon the stock itself. Upon this naked point of profit and loss, to be decided by a rule in arithmetic, we have sustained a direct and heavy loss. The stock held by the United States, as every body knows, was subscribed, not paid. It was a stock note, deposited for seven millions of dollars, bearing an interest of five per cent. The inducement to this subscription was the seductive conception that, by paying five per cent. on its note, the United States would clear four or five per cent. in getting a dividend of eight or ten. This was the inducement; now for the realization of this fine conception. Let us see it. Here it is; an official return, from the Register of the Treasury of interest paid, and of dividends received. The account stands thus:

"Disadvantageous as this partnership must be to the United States in a moneyed point of view, there is a far more grave and serious aspect under which to view it. It is the political aspect, resulting from the union between the bank and the government. This union has been tried in England, and has been found there to be just as disastrous a conjunction as the union between church and state. It is the conjunction of the lender and the borrower, and Holy Writ has told us which of these categories will be master of the other. But suppose they agree to drop rivalry, and unite their resources. Suppose they combine, and make a push for political power: how great is the mischief which they may not accomplish! But, on this head, I wish to use the language of one of the brightest patriots of Great Britain; one who has shown himself, in these modern days, to be the worthy successor of those old iron barons whose patriotism commanded the unpurchasable eulogium of the elder Pitt. I speak of Sir William Pulteney, and his speech against the Bank of England, in 1797.

"THE SPEECH: – EXTRACT"'I have said enough to show that government has been rendered dependent on the bank, and more particularly so in the time of war; and though the bank has not yet fallen into the hands of ambitious men, yet it is evident that it might, in such hands, assume a power sufficient to control and overawe, not only the ministers, but king, lords, and commons. * * * * * * As the bank has thus become dangerous to government, it might, on the other hand, by uniting with an ambitious minister, become the means of establishing a fourth estate, sufficient to involve this nation in irretrievable slavery, and ought, therefore, to be dreaded as much as a certain East India bill was justly dreaded, at a period not very remote. I will not say that the present minister (the younger Pitt), by endeavoring, at this crisis, to take the Bank of England under his protection, can have any view to make use, hereafter, of that engine to perpetuate his own power, and to enable him to domineer over our constitution: if that could be supposed, it would only show that men can entertain a very different train of ideas, when endeavoring to overset a rival, from what occurs to them when intending to support and fix themselves. My object is to secure the country against all risk either from the bank as opposed to government, or as the engine of ambitious men.'

"And this is my object also. I wish to secure the Union from all chance of harm from this bank. I wish to provide against its friendship, as well as its enmity – against all danger from its hug, as well as from its blow. I wish to provide against all risk, and every hazard; for, if this risk and hazard were too great to be encountered by King, Lords, and Commons, in Great Britain, they must certainly be too great to be encountered by the people of the United States, who are but commons alone.

"10. To have foreigners for partners. This, Mr. President, will be a strange story to be told in the West. The downright and upright people of that unsophisticated region believe that words mean what they signify, and that 'the Bank of the United States' is the Bank of the United States. How great then must be their astonishment to learn that this belief is a false conception, and that this bank (its whole name to the contrary notwithstanding) is just as much the bank of foreigners as it is of the federal government. Here I would like to have the proof – a list of the names and nations, to establish this almost incredible fact. But I have no access except to public documents, and from one of these I learn as much as will answer the present pinch. It is the report of the Committee of Ways and Means, in the House of Representatives, for the last session of Congress. That report admits that foreigners own seven millions of the stock of this bank; and every body knows that the federal government owns seven millions also.

"Thus it is proved that foreigners are as deeply interested in this bank as the United States itself. In the event of a renewal of the charter they will be much more deeply interested than at present; for a prospect of a rise in the stock to two hundred and fifty, and the unsettled state of things in Europe, will induce them to make great investments. It is to no purpose to say that the foreign stockholders cannot be voters or directors. The answer to that suggestion is this: the foreigners have the money; they pay down the cash, and want no accommodations; they are lenders, not borrowers; and in a great moneyed institution, such stockholders must have the greatest influence. The name of this bank is a deception upon the public. It is not the bank of the federal government, as its name would import, nor of the States which compose this Union; but chiefly of private individuals, foreigners as well as natives, denizens, and naturalized subjects. They own twenty-eight millions of the stock, the federal government but seven millions, and these seven are precisely balanced by the stock of the aliens. The federal government and the aliens are equal, owning one fifth each; and there would be as much truth in calling it the English Bank as the Bank of the United States. Now mark a few of the privileges which this charter gives to these foreigners. To be landholders, in defiance of the State laws, which forbid aliens to hold land; to be landlords by incorporation, and to hold American citizens for tenants; to hold lands in mortmain; to be pawnbrokers and merchants by incorporation; to pay the revenue of the United States in their own notes; in short, to do every thing which I have endeavored to point out in the long and hideous list of exclusive privileges granted to this bank. If I have shown it to be dangerous for the United States to be in partnership with its own citizens, how much stronger is not the argument against a partnership with foreigners? What a prospect for loans when at war with a foreign power, and the subjects of that power large owners of the bank here, from which alone, or from banks liable to be destroyed by it, we can obtain money to carry on the war! What a state of things, if, in the division of political parties, one of these parties and the foreigners, coalescing, should have the exclusive control of all the money in the Union, and, in addition to the money, should have bodies of debtors, tenants, and bank officers stationed in all the States, with a supreme and irresponsible system of centralism to direct the whole! Dangers from such contingencies are too great and obvious to be insisted upon. They strike the common sense of all mankind, and were powerful considerations with the old whig republicans for the non-renewal of the charter of 1791. Mr. Jefferson and the whig republicans staked their political existence on the non-renewal of that charter. They succeeded; and, by succeeding, prevented the country from being laid at the mercy of British and ultra-federalists for funds to carry on the last war. It is said the United States lost forty millions by using depreciated currency during the last war. That, probably, is a mistake of one half. But be it so! For what are forty millions compared to the loss of the war itself – compared to the ruin and infamy of having the government arrested for want of money – stopped and paralyzed by the reception of such a note as the younger Pitt received from the Bank of England in 1795?

"11. Exemption from due course of law for violations of its charter. – This is a privilege which affects the administration of justice, and stands without example in the annals of republican legislation. In the case of all other delinquents, whether persons or corporations, the laws take their course against those who offend them. It is the right of every citizen to set the laws in motion against every offender; and it is the constitution of the law, when set in motion, to work through, like a machine, regardless of powers and principalities, and cutting down the guilty which may stand in its way. Not so in the case of this bank. In its behalf, there are barriers erected between the citizen and his oppressor, between the wrong and the remedy, between the law and the offender. Instead of a right to sue out a scire facias or a quo warranto, the injured citizen, with an humble petition in his hand, must repair to the President of the United States, or to Congress, and crave their leave to do so. If leave is denied (and denied it will be whenever the bank has a peculiar friend in the President, or a majority of such friends in Congress, the convenient pretext being always at hand that the general welfare requires the bank to be sustained), he can proceed no further. The machinery of the law cannot be set in motion, and the great offender laughs from behind his barrier at the impotent resentment of its helpless victim. Thus the bank, for the plainest violations of its charter, and the greatest oppressions of the citizen, may escape the pursuit of justice. Thus the administration of justice is subject to be strangled in its birth for the shelter and protection of this bank. But this is not all. Another and most alarming mischief results from the same extraordinary privilege. It gives the bank a direct interest in the presidential and congressional elections: it gives it need for friends in Congress and in the presidential chair. Its fate, its very existence, may often depend upon the friendship of the President and Congress; and, in such cases, it is not in human nature to avoid using the immense means in the hands of the bank to influence the elections of these officers. Take the existing fact – the case to which I alluded at the commencement of this speech. There is a case made out, ripe with judicial evidence, and big with the fate of the bank. It is a case of usury at the rate of forty-six per cent., in violation of the charter, which only admits an interest of six. The facts were admitted, in the court below, by the bank's demurrer; the law was decided, in the court above, by the supreme judges. The admission concludes the facts; the decision concludes the law. The forfeiture of the charter is established; the forfeiture is incurred; the application of the forfeiture alone is wanting to put an end to the institution. An impartial President or Congress might let the laws take their course; those of a different temper might interpose their veto. What a crisis for the bank! It beholds the sword of Damocles suspended over its head! What an interest in keeping those away who might suffer the hair to be cut!

"12. To have all these unjust privileges secured to the corporators as a monopoly, by a pledge of the public faith to charter no other bank. – This is the most hideous feature in the whole mass of deformity. If these banks are beneficial institutions, why not several? one, at least, and each independent of the other, to each great section of the Union? If malignant, why create one? The restriction constitutes the monopoly, and renders more invidious what was sufficiently hateful in itself. It is, indeed, a double monopoly, legislative as well as banking; for the Congress of 1816 monopolized the power to grant these monopolies. It has tied up the hands of its successors; and if this can be done on one subject, and for twenty years, why not upon all subjects, and for all time? Here is the form of words which operate this double engrossment of our rights: 'No other bank shall be established by any future law of Congress, during the continuance of the corporation hereby enacted, for which the faith of Congress is hereby pledged;' with a proviso for the District of Columbia. And that no incident might be wanting to complete the title of this charter, to the utter reprobation of whig republicans, this compound monopoly, and the very form of words in which it is conceived, is copied from the charter of the Bank of England! – not the charter of William and Mary, as granted in 1694 (for the Bill of Rights was then fresh in the memories of Englishmen), but the charter as amended, and that for money, in the memorable reign of Queen Anne, when a tory queen, a tory ministry, and a tory parliament, and the apostle of toryism, in the person of Dr. Sacheverell, with his sermons of divine right, passive obedience, and non-resistance, were riding and ruling over the prostrate liberties of England! This is the precious period, and these the noble authors, from which the idea was borrowed, and the very form of words copied, which now figure in the charter of the Bank of the United States, constituting that double monopoly, which restricts at once the powers of Congress and the rights of the citizens.