полная версия

полная версияThe Moral and Intellectual Diversity of Races

It is necessary, then, to show what degeneracy is. This step in advance, Mr. Gobineau attempts to make. He shows that each race is distinguished by certain capabilities, which, if its civilizing genius is sufficiently strong to enable it to assume a rank among the nations of the world, determine the character of its social and political development. Like the Phenicians, it may become the merchant and barterer of the world; or, like the Greeks, the teacher of future generations; or, like the Romans, the model-giver of laws and forms. Its part in the drama of history may be an humble one or a proud, but it is always proportionate to its powers. These powers, and the instincts or aspirations which spring from them, never change as long as the race remains pure. They progress and develop themselves, but never alter their nature. The purposes of the race are always the same. It may arrive at great perfection in the useful arts, but, without infiltration of a different element, will never be distinguished for poetry, painting, sculpture, etc.; and vice versa. Its nature may be belligerent, and it will always find causes for quarrel; or it may be pacific, and then it will manage to live at peace, or fall a prey to a neighbor.

In the same manner, the government of a race will be in accordance with its instincts, and here I have the weighty authority of the author of Democracy in America, in my favor, and the author's whom I am illustrating. "A government," says De Tocqueville,24 "retains its sway over a great number of citizens, far less by the voluntary and rational consent of the multitude, than by that instinctive, and, to a certain extent, involuntary agreement, which results from similarity of feelings, and resemblances of opinions. I will never admit that men constitute a social body, simply because they obey the same head and the same laws. A society can exist only when a great number of men consider a great number of things in the same point of view; when they hold the same opinions upon many subjects, and when the same occurrences suggest the same thoughts and impressions to their minds." The laws and government of a nation are always an accurate reflex of its manners and modes of thinking. "If, at first, it would appear," says Mr. Gobineau, "as if, in some cases, they were the production of some superior individual intellect, like the great law-givers of antiquity; let the facts be more carefully examined, and it will be found that the law-giver – if wise and judicious – has contented himself with consulting the genius of his nation, and giving a voice to the common sentiment. If, on the contrary, he be a theorist like Draco, his system remains a dead letter, soon to be superseded by the more judicious institutions of a Solon who aims to give to his countrymen, not the best laws possible, but the best he thinks them capable of receiving." It is a great and a very general error to suppose that the sense of a nation will always decide in favor of what we term "popular" institutions, that is to say, such in which each individual shares more or less immediately in the government. Its genius may tend to the establishment of absolute authority, and in that case the autocrat is but an impersonation of the vox populi, by which he must be guided in his policy. If he be too deaf or rash to listen to it, his own ruin will be the inevitable consequence, but the nation persists in the same career.

The meaning of the word degeneracy is now obvious. This inevitable evil is concealed in the very successes to which a nation owes its splendor. Whether, like the Persians, Romans, &c., it is swallowed up and absorbed by the multitudes its arms have subjected, or whether the ethnical mixture proceeds in a peaceful manner, the result is the same. Even where no foreign conquests add suddenly hundreds of thousands of a foreign population to the original mass, the fertility of uncultivated fields, the opulence of great commercial cities, and all the advantages to be found in the bosom of a rising nation, accomplish it, if in a less perceptible, in a no less certain manner. The two young nations of the world are now the United States and Russia. See the crowds which are thronging over the frontiers of both. Both already count their foreign population by millions. As the original population – the initiatory element of the whole mass – has no additions to its numbers but its natural increase, it follows that the influent elements must, in course of time, be of equal strength, and the influx still continuing, finally absorb it altogether. Sometimes a nation establishes itself upon the basis of a much more numerous conquered population, as in the case of the Frankish conquerors of Gaul; then the amalgamation of ranks and classes produces the same results as foreign immigration. It is clear that each new ethnical element brings with it its own characteristics or instincts, and according to the relative strength of these will be the modifications in government, social relations, and the whole tendencies of the race. The modifications may be for the better, they may be for the worse; they may be very gradual, or very sudden, according to the merit and power of the foreign influence; but in course of time they will amount to radical, positive changes, and then the original nation has ceased to exist.

This is the natural death of human societies. Sometimes they expire gently and almost imperceptibly; oftener with a convulsion and a crash. I shall attempt to explain my meaning by a familiar simile. A mansion is built which in all respects suits the taste and wants of the owner. Succeeding generations find it too small, too dark, or otherwise ill adapted to their purposes. Respect for their progenitor, and family association, prevent, at first, very extensive changes, still each one makes some; and as these associations grow fainter, the changes become more radical, until at last nothing of the old house remains. But if it had previously passed into the hands of a stranger, who had none of these associations to venerate and respect, he would probably have pulled it down at once and built another.

An empire, then, falls, when the vitalizing principle which gave it birth is exhausted; when its parts are connected by none but artificial ties, and artificial ties are all those which unite races possessed of different instincts. This idea is expressed in the beautiful image of the inspired prophet, when he tells the mighty king that great truth, which so many refuse to believe, that all earthly kingdoms must perish until "the God of Heaven set up a kingdom which shall never be destroyed."25 "Thou, O king, sawest, and behold a great image. This great image, whose brightness was excellent, stood before thee, and the form thereof was terrible. This image's head was of fine gold, his breast and his arms of silver, his belly and his thighs of brass, his legs of iron, his feet part of iron and part of clay. Thou sawest till that a stone was cut without hands, which smote the image upon his feet that were of iron and clay, and brake them to pieces. Then was the iron, the clay, the brass, the silver, and the gold, broken to pieces together, and became like the chaff of the summer threshing-floors; and the wind carried them away, that no place was found for them."26

I have now illustrated, to the best of my abilities, several of the most important propositions of Mr. Gobineau, and attempted to sustain them by arguments and examples different from those used by the author. For a more perfect exposition I must refer the reader to the body of the work. My purpose was humbly to clear away such obstacles as the author has left in the path, and remove difficulties that escaped his notice. The task which I have set myself, would, however, be far from accomplished, were I to pass over what I consider a serious error on his part, in silence and without an effort at emendation.

Civilization, says Mr. Gobineau, arises from the combined action and mutual reaction of man's moral aspirations, and the pressure of his material wants. This, in a general sense, is obviously true. But let us see the practical application. I shall endeavor to give a concise abstract of his views, and then to point out where and why he errs.

In some races, says he, the spiritual aspirations predominate over their physical desires, in others it is the reverse. In none are either entirely wanting. According to the relative proportion and intensity of either of these influences, which counteract and yet assist each other, the tendency of the civilization varies. If either is possessed in but a feeble degree, or if one of them so greatly outweighs the other as to completely neutralize its effects, there is no civilization, and never can be one until the race is modified by intermixture with one of higher endowments. But if both prevail to a sufficient extent, the preponderance of either one determines the character of the civilization. In the Chinese, it is the material tendency that prevails, in the Hindoo the other. Consequently we find that in China, civilization is principally directed towards the gratification of physical wants, the perfection of material well-being. In other words, it is of an eminently utilitarian character, which discourages all speculation not susceptible of immediate practical application.

This well describes the Chinese, and is precisely the picture which M. Huc, who has lived among them for many years, and has enjoyed better opportunities for studying their genius than any other writer, gives of them in his late publication.27

Hindoo culture, on the contrary, displays a very opposite tendency. Among that nation, everything is speculative, nothing practical. The toils of human intellect are in the regions of the abstract where the mind often loses itself in depths beyond its sounding. The material wants are few and easily supplied. If great works are undertaken, it is in honor of the gods, so that even their physical labor bears homage to the invisible rather than the visible world. This also is a tolerably correct picture.

He therefore divides all races into these two categories, taking the Chinese as the type of the one and the Hindoos as that of the other. According to him, the yellow races belong pre-eminently to the former, the black to the latter, while the white are distinguished by a greater intensity and better proportion of the qualities of both. But this division, and no other is consistent with the author's proposition, by assuming that in the black races the moral preponderates over the physical tendency, comes in direct conflict not only with the plain teachings of anatomy, but with all we know of the history of those races. I shall attempt to show wherein Mr. Gobineau's error lies, an error from the consequences of which I see no possibility for him to escape, and suggest an emendation which, so far from invalidating his general position, tends rather to confirm and strengthen it. In doing so, I am actuated by the belief that even if I err, I may be useful by inviting others more capable to the task of investigation. Suggestions on important subjects, if they serve no other purpose than to provoke inquiry, are never useless. The alchemists of the Middle Ages, in their frivolous pursuit of impossibilities, discovered many invaluable secrets of nature and laid the foundation of that science which, by explaining the intimate mutual action of all natural bodies, has become the indispensable handmaiden of almost every other.

The error, it seems to me, lies in the same confusion of distinct ideas, to which I had already occasion to advert. In ordinary language, we speak of the physical and moral nature of man, terming physical whatever relates to his material, and moral what relates to his immaterial being. Again, we speak of mind, and though in theory we consider it as a synonyme of soul, in practical application it has a very different signification. A person may cultivate his mind without benefiting his soul, and the term a superior mind, does not necessarily imply moral excellency. That mental qualifications or acquisitions are in no way connected with sound morality or true piety, I have pointed out before. Should any further illustrations be necessary, I might remark that the greatest monsters that blot the page of history, have been, for the most part, men of what are called superior minds, of great intellectual attainments. Indeed, wickedness is seldom very dangerous, unless joined to intellect, as the common sense of mankind has expressed in the adage that a fool is seldom a knave. We daily see men perverting the highest mental gifts to the basest purposes, a fact which ought to be carefully weighed by those who believe that education consists in the cultivation of the intellect only. I therefore consider the moral endowments of man as practically different from the mental or intellectual, at least in their manifestations, if not in their essence. To define my idea more clearly, let me attempt to explain the difference between what I term the moral and the intellectual nature of man. I am aware of the dangerous nature of the ground I am treading, but shall nevertheless make the attempt to show that it is in accordance with the spirit of religion to consider what in common parlance is called the moral attributes of man, and which would be better expressed by the word psychical, as divisible into two, the strictly moral, and the intellectual.

The former is what leads man to look beyond his earthly existence, and gives even the most brutish savage some vague idea of a Deity. I am making no rash or unfounded assertion when I declare, Mr. Locke's weighty opinion to the contrary notwithstanding, that no tribe has ever been discovered in which some notion of this kind, however rude, was wanting, and I consider it innate – a yearning, as it were, of the soul towards the regions to which it belongs. The feeling of religion is implanted in our breast; it is not a production of the intellect, and this the Christian church confirms when it declares that faith we owe to the grace of God.

Intellect is that faculty of soul by which it takes cognizance of, classes and compares the facts of the material world. As all perceptions are derived through the senses, it follows that upon the nicety of these its powers must in a great measure depend. The vigor and delicacy of the nerves, and the size and texture of the brain in which they all centre, form what we call native intellectual gifts. Hence, when the body is impaired, the mind suffers; "mens sana in corpore sano;" hence, a fever prostrates, and may forever destroy, the most powerful intellect; a glass of wine may dim and distort it. Here, then, is the grand distinction between soul and mind. The latter, human wickedness may annihilate; the former, man killeth not. I should wish to enter more fully upon this investigation, not new, indeed, in speculative science, yet new in the application I purpose to make of it, were it not for fear of wearying my reader, to whom my only apology can be, that the discussion is indispensable to the proper investigation of the moral and intellectual diversities of races. When I say moral diversities, I do not mean that man's moral endowments, strictly speaking, are unequal. This assertion I am not prepared to make, because – as religion is accessible and comprehensible to them all – it may be supposed that these are in all cases equal. But I mean that the manifestation of these moral endowments varies, owing to causes which I am now about to consider. I have said that the moral nature of man leads him to look beyond the confines of the material world. This, when not assisted by revelation, he attempts to do by means of his intellect. The intellect is, as it were, the visual organ by which the soul scans the abyss between the present and the future existence. According to the dimness or brightness of this mental eye, are his perceptions. If the intellectual capacity is weak, he is content with a grovelling conception of the Deity; if powerful, he erects an elaborate fabric of philosophical speculations. But, as the Almighty has decreed that human intellect, even in its sublimest flight, cannot soar to His presence; it follows that the most elaborate fabric of the philosopher is still a human fabric, that the most perfect human theology is still human, and hence – the necessity of revelation. This divine light, which His mercy has vouchsafed us, dispenses with, and eclipses, the feeble glimmerings of human intellect. It illumines as well the soul of the rude savage as of the learned theologian; of the illiterate as of the erudite. Nay, very often the former has the advantage, for the erudite philosopher is prone to think his own lamp all-sufficient. If it be objected that a highly cultivated mind, if directed to rightful purposes, will assist in gaining a nobler conception of the Deity, I shall not contradict, for in the study of His works, we learn still more to admire the Maker. But I insist that true piety can, and does exist without it, and let those who trust so much in their own powers beware lest they lean upon a broken staff.

The strictly moral attributes of man, therefore, those attributes which enable him to communicate with his Maker, are common – probably in equal degree – to all men, and to all races of men. But his communications with the external world depend on his physical conformation. The body is the connecting link between the spirit and the material world, and, by its intimate relations to both, specially adapted to be the means of communication between them. There seems to me nothing irrational or irreligious in the doctrine that, according to the perfectness of this means of communication, must be the intercourse between the two. A person with dull auditory organs can never appreciate music, and whatever his talents otherwise may be, can never become a Meyerbeer or a Mozart. Upon quickness of perception, power of analysis and combination, perseverance and endurance, depend our intellectual faculties, both in their degree and their kind; and are not they blunted or otherwise modified in a morbid state of the body? I consider it therefore established beyond dispute, that a certain general physical conformation is productive of corresponding mental characteristics. A human being, whom God has created with a negro's skull and general physique, can never equal one with a Newton's or a Humboldt's cranial development, though the soul of both is equally precious in the eyes of the Lord, and should be in the eyes of all his followers. There is no tendency to materialism in this idea; I have no sympathy with those who deny the existence of the soul, because they cannot find it under the scalpel, and I consider the body not the mental agent, but the servant, the tool.

It is true that science has not discovered, and perhaps never will discover, what physical differences correspond to the differences in individual minds. Phrenology, starting with brilliant promises, and bringing to the task powers of no mean order, has failed. But there is a vast difference between the characteristics by which we distinguish individuals of the same race, and those by which we distinguish races themselves. The former are not strictly – at least not immediately – hereditary, for the child most often differs from both parents in body and mind, because no two individuals, as no two leaves of one tree, are precisely alike. But, although every oak-leaf differs from its fellow, we know the leaf of the oak-tree from that of the beech, or every other; and, in the same manner, races are distinguished by peculiarities which are hereditary and permanent. Thus, every negro differs from every other negro, else we could not tell them apart; yet all, if pure blood, have the same characteristics in common that distinguish them from the white. I have been prolix, but intentionally so, in my discrimination between individual distinction and those of race, because of the latter, comparative anatomy takes cognizance; the former are left to phrenology, and I wished to remove any suspicion that in the investigation of moral and intellectual diversities of races, recourse must be had to the ill-authenticated speculations of a dubious science. But, from the data of comparative anatomy, attained by a slow and cautious progress, we deduce that races are distinguished by certain permanent physical characteristics; and, if these physical characteristics correspond to the mental, it follows as an obvious conclusion that the latter are permanent also. History ratifies the conclusion, and the common sense of mankind practically acquiesces in it.

To return, then, to our author. I would add to his two elements of civilization a third – intellect per se; or rather, to speak more correctly, I would subdivide one of his elements into two, of which one is probably dependent on physical conformation. The combinations will then be more complex, but will remove every difficulty.

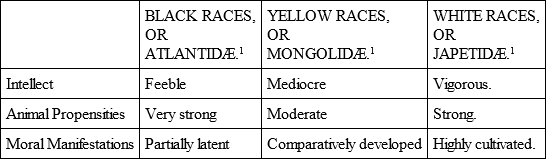

I remarked that although we may consider all races as possessed of equal moral endowments, we yet may speak of moral diversities; because, without the light of revelation, man has nothing but his intellect whereby to compass the immaterial world, and the manifestation of his moral faculties must therefore be in proportion to the clearness of his intellectual, and their preponderance over the animal tendencies. The three I consider as existing about in the following relative proportions in the three great groups under which Mr. Gobineau and Mr. Latham28 have arranged the various races – a classification, however, which, as I already observed, I cannot entirely approve.

But the races comprised in each group vary among themselves, if not with regard to the relative proportion in which they possess the elements of civilization, at least in their intensity. The following formulas will, I think, apply to the majority of cases, and, at the same time, bring out my idea in a clearer light: —

If the animal propensities are strongly developed, and not tempered by the intellectual faculties, the moral conceptions must be exceedingly low, because they necessarily depend on the clearness, refinement, and comprehensiveness of the ideas derived from the material world through the senses. The religious cravings will, therefore, be contented with a gross worship of material objects, and the moral sense degenerate into a grovelling superstition. The utmost elevation which a population, so constituted, can reach, will be an unconscious impersonation of the good aspirations and the evil tendencies of their nature under the form of a good and an evil spirit, to the latter of which absurd and often bloody homage is paid. Government there can be no other than the right which force gives to the strong, and its forms will be slavery among themselves, and submissiveness of all to a tyrannical absolutism.

When the same animal propensities are combined with intellect of a higher order, the moral faculties have more room for action. The penetration of intellect will not be long in discovering that the gratification of physical desires is easiest and safest in a state of order and stability. Hence a more complex system of legislation both social and political. The conceptions of the Deity will be more elevated and refined, though the idea of a future state will probably be connected with visions of material enjoyment, as in the paradise of the Mohammedans.

Where the animal propensities are weak and the intellect feeble, a vegetating national life results. No political organization, or of the very simplest kind. Few laws, for what need of restraining passions which do not exist. The moral sense content with the vague recognition of a superior being, to whom few or no rites are rendered.

1. According to Latham's classification, op. cit.

But when the animal propensities are so moderate as to be subordinate to an intellect more or less vigorous, the moral aspirations will yearn towards the regions of the abstract. Religion becomes a system of metaphysics, and often loses itself in the mazes of its own subtlety. The political organization and civil legislation will be simple, for there are few passions to restrain; but the laws which regulate social intercourse will be many and various, and supposed to emanate directly from the Deity.

Strong animal passions, joined to an intellect equally strong, allow the greatest expanse for the moral sense. Political organizations the most complex and varied, social and civil laws the most studied, will be the outward character of a society composed of such elements. Internally we shall perceive the greatest contrasts of individual goodness and wickedness. Religion will be a symbolism of human passions and the natural elements for the many, an ingenious fabric of moral speculations for the few.