полная версия

полная версияThe Moral and Intellectual Diversity of Races

Such is the state of civilization in France. It may be asserted that of a population of thirty-six millions, ten participate in the ideas and mode of thinking upon which our civilization is based, while the remaining twenty-six altogether ignore them, are indifferent and even hostile to them, and this computation would, I think, be even more flattering than the real truth. Nor is France an exception in this respect. The picture I have given applies to the greater part of Europe. Our civilization is suspended, as it were, over an unfathomable gulf, at the bottom of which there slumber elements which may, one day, be roused and prove fearfully, irresistibly destructive. This is an awful, an ominous truth. Upon its ultimate consequences it is painful to reflect. Wisdom may, perhaps, foresee the storm, but can do little to avert it.

But ignored, despised, or hated as it is by the greater number of those over whom it extends its dominion, our civilization is, nevertheless, one of the grandest, most glorious monuments of the human mind. In the inventive, initiatory quality it does not surpass, or even equal some of its predecessors, but in comprehensiveness it surpasses all. From this comprehensiveness arise its powers of appropriation, of conquest; for, to comprehend is to seize, to possess. It has appropriated all their acquisitions, and has remodelled, reconstructed them. It did not create the exact sciences, but it has given them their exactitude, and has disembarrassed them from the divagations from which, by a singular paradox, they were anciently less free than any other branch of knowledge. Thanks to its discoveries, the material world is better known than at any other epoch. The laws by which nature is governed, it has, in a great measure, succeeded in unveiling, and it has applied them so as to produce results truly wonderful. Gradually, and by the clearness and correctness of its induction, it has reconstructed immense fragments of history, of which the ancients had no knowledge; and as it recedes from the primitive ages of the world, it penetrates further into the mist that obscures them. These are great points of superiority, and which cannot be contested.

But these being admitted, are we authorized to conclude – as is so generally assumed as a matter of course – that the characteristics of our civilization are such as to entitle it to the pre-eminence among all others? Let us examine what are its peculiar excellencies. Thanks to the prodigious number of various elements that contributed to its formation, it has an eclectic character which none of its predecessors or contemporaries possess. It unites and combines so many various qualities and faculties, that its progress is equally facile in all directions; and it has powers of analysis and generalization so great, that it can embrace and appropriate all things, and, what is more, apply them to practical purposes. In other words, it advances at once in a number of different directions, and makes valuable conquests in all, but it cannot be said that it advances at the same time furthest in all. Variety, perhaps, rather than great intensity, is its characteristic. If we compare its progress in any one direction with what has been done by others in the same, we shall find that in few, indeed, can our civilization claim pre-eminence. I shall select three of the most striking features of every civilization; the art of government, the state of the fine arts, and refinement of manners.

In the art of government, the civilization of Europe has arrived at no positive result. In this respect, it has been unable to assume a definite character. It has laid down no principles. In every country over which its dominion extends, it is subservient to the exigencies of the various races which it has aggregated, but not united. In England, Holland, Naples, and Russia, political forms are still in a state of comparative stability, because either the whole population, or the dominant portion of it, is composed of the same or homogeneous elements. But everywhere else, especially in France, Central Italy, and Germany, where the ethnical diversity is boundless, governmental theories have never risen to the dignity of recognized truth; political science consisted in an endless series of experiments. Our civilization, therefore, being unable to assume a definite political feature, is devoid, in this respect, of that stability which I comprised as an essential feature in my definition of a civilization. This impotency is not found in many other civilizations which we deem inferior. In the Celestial Empire, in the Buddhistic and Brahminical societies, the political feature of the civilization is clearly enounced, and clearly understood by each individual member. In matters of politics all think alike; under a wise administration, when the secular institutions produce beneficent fruits, all rejoice; when in unskilled or malignant hands, they endanger the public welfare, it is a misfortune to be regretted as we regret our own faults; but no circumstance can abate the respect and admiration with which they are regarded. It may be desirable to correct abuses that have crept into them, but never to replace them by others. It cannot be denied that these civilizations, therefore, whatever we may think of them in other respects, enjoy a guarantee of durability, of longevity, in which ours is sadly wanting.

With regard to the arts, our civilization is decidedly inferior to others. Whether we aim at the grand or the beautiful, we cannot rival either the imposing grandeur of the civilization of Egypt, of India, or even of the ancient American empires, nor the elegant beauty of that of Greece. Centuries hence – when the span of time allotted to us shall have been consumed, when our civilization, like all that preceded it, shall have sunk in the dim shades of the past, and have become a matter of inquiry only to the historical student – some future traveller may wander among the forests and marshes on the banks of the Thames, the Seine, or the Rhine, but he will find no glorious monuments of our grandeur; no sumptuous or gigantic ruins like those of Philæ, of Nineveh, of Athens, of Salsetta, or of Tenochtitlan. A remote posterity may venerate our memory as their preceptors in exact sciences. They may admire our ingenuity, our patience, the perfection to which we have carried inductive reasoning – not so our conquests in the regions of the abstract. In poesy we can bequeath them nothing. The boundless admiration which we bestow upon the productions of foreign civilizations both past and present, is a positive proof of our own inferiority in this respect.115

Perhaps the most striking features of a civilization, though not a true standard of its merit, is the degree of refinement which it has attained. By refinement I mean all the luxuries and amenities of life, the regulations of social intercourse, delicacy of habits and tastes. It cannot be denied that in all these we do not surpass, nor even equal, many former as well as contemporaneous civilizations. We cannot rival the magnificence of the latter days of Rome, or of the Byzantine empire; we can but imagine the gorgeous luxury of Eastern civilizations; and in our own past history we find periods when the modes of living were more sumptuous, polished intercourse regulated by a higher and more exacting standard, when taste was more cultivated, and habits more refined. It is true, that we are amply compensated by a greater and more general diffusion of the comforts of life; but in its exterior manifestations, our civilization compares unfavorably with many others, and might almost be called shabby.

Before concluding this digression upon civilization, which has already extended perhaps too far, it may not be unnecessary to reiterate the principal ideas which I wished to present to the mind of the reader. I have endeavored to show that every civilization derives its peculiar character from the race which gave the initiatory impulse. The alteration of this initiatory principle produces corresponding modifications, and even total changes, in the character of the civilization. Thus our civilization owes its origin to the Teutonic race, whose leading characteristic was an elevated utilitarianism. But as these races ingrafted their mode of culture upon stocks essentially different, the character of the civilization has been variously modified according to the elements which it combined and amalgamated. The civilization of a nation, therefore, exhibits the kind and degree of their capabilities. It is the mirror in which they reflect their individuality.

I shall now return to the natural order of my deductions, the series of which is yet far from being complete. I commenced by enouncing the truth that the existence and annihilation of human societies depended upon immutable and uniform laws. I have proved the insufficiency of adventitious circumstances to produce these phenomena, and have traced their causes to the various capabilities of different human groups; in other words, to the moral and intellectual diversity of races. Logic, then, demands that I should determine the meaning and bearing of the word race, and this will be the object of the next chapter.

CHAPTER X.

QUESTION OF UNITY OR PLURALITY OF SPECIES

Systems of Camper, Blumenbach, Morton, Carus – Investigations of Owen, Vrolik, Weber – Prolificness of hybrids, the great scientific stronghold of the advocates of unity of species.

It will be necessary to determine first the physiological bearing of the word race.

In the opinion of many scientific observers, who judge from the first impression, and take extremes116 as the basis of their reasoning, the groups of the human family are distinguished by differences so radical and essential, that it is impossible to believe them all derived from the same stock. They, therefore, suppose several other genealogies besides that of Adam and Eve. According to this doctrine, instead of but one species in the genus homo, there would be three, four, or even more, entirely distinct ones, whose commingling would produce what the naturalists call hybrids.

General conviction is easily secured in favor of this theory, by placing before the eyes of the observer instances of obvious and striking dissimilarities among the various groups. The critic who has before him a human subject with a skin of olive-yellow; black, straight, and thin hair; little, if any beard, eyebrows, and eyelashes; a broad and flattened face, with features not very distinct; the space between the eyes broad and flat; the orbits large and open; the nose flattened; the cheeks high and prominent; the opening of the eyelids narrow, linear, and oblique, the inner angle the lowest; the ears and lips large; the forehead low and slanting, allowing a considerable portion of the face to be seen when viewed from above; the head of somewhat a pyramidal form; the limbs clumsy; the stature humble; the whole conformation betraying a marked tendency to obesity:117 the critic who examines this specimen of humanity, at once recognizes a well characterized and clearly defined type, the principal features of which will readily be imprinted in his memory.

Let us suppose him now to examine another individual: a negro, from the western coast of Africa. This specimen is of large size, and vigorous appearance. The color is a jetty black, the hair crisp, generally called woolly; the eyes are prominent, and the orbits large; the nose thick, flat, and confounded with the prominent cheeks; the lips very thick and everted; the jaws projecting, and the chin receding; the skull assuming the form called prognathous. The low forehead and muzzle-like elongation of the jaws, give to the whole being an almost animal appearance, which is heightened by the large and powerful lower-jaw, the ample provision for muscular insertions, the greater size of cavities destined for the reception of the organs of smell and sight, the length of the forearm compared with the arm, the narrow and tapering fingers, etc. "In the negro, the bones of the leg are bent outwards; the tibia and fibula are more convex in front than in the European; the calves of the legs are very high, so as to encroach upon the hams; the feet and hand, but particularly the former, are flat; the os calcis, instead of being arched, is continued nearly in a straight line with the other bones of the foot, which is remarkably broad."118

In contemplating a human being so formed, we are involuntarily reminded of the structure of the ape, and we feel almost inclined to admit that the tribes of Western Africa are descended from a stock which bears but a slight and general resemblance to that of the Mongolian family.

But there are some groups, whose aspect is even less flattering to the self-love of humanity than that of the Congo. It is the peculiar distinction of Oceanica to furnish about the most degraded and repulsive of those wretched beings, who seem to occupy a sort of intermediate station between man and the mere brute. Many of the groups of that latest-discovered world, by the excessive leanness and starveling development of their limbs;119 the disproportionate size of their heads; the excessive, hopeless stupidity stamped upon their countenances; present an aspect so hideous and disgusting, that – contrasted with them – even the negro of Western Africa gains in our estimation, and seems to claim a less ignoble descent than they.

We are still more tempted to adopt the conclusions of the advocates for the plurality of species, when, after having examined types taken from every quarter of the globe, we return to the inhabitants of Europe and Southern and Western Asia. How vast a superiority these exhibit in beauty, correctness of proportion, and regularity of features! It is they who enjoy the honor of having furnished the living models for the unrivalled masterpieces of ancient sculpture. But even among these races there has existed, since the remotest times, a gradation of beauty, at the head of which the European may justly be placed, as well for symmetry of limbs as for vigorous muscular development. Nothing, then, would appear more reasonable than to pronounce the different types of mankind as foreign to each other as are animals of different species.

Such, indeed, was the conclusion arrived at by those who first systematized their observations, and attempted to establish a classification; and so far as this classification depended upon general facts, it seemed incontestable.

Camper took the lead. He was not content with deciding upon merely superficial appearances, but wished to rest his demonstrations upon a mathematical basis, by defining, anatomically, the distinguishing characteristics of different types. If he succeeded in this, he would thereby establish a strict and logical method of treating the subject, preclude all doubt, and give to his opinions that rigorous precision without which there is no true science. I borrow from Mr. Prichard,120 Camper's own account of his method. "The basis on which the distinction of nations121 is founded, says he, may be displayed by two straight lines; one of which is to be drawn through the meatus auditorius (the external entrance of the ear) to the base of the nose; and the other touching the prominent centre of the forehead, and falling thence on the most prominent part of the upper jaw-bone, the head being viewed in profile. In the angle produced by these two lines, may be said to consist, not only the distinctions between the skulls of the several species of animals, but also those which are found to exist between different nations; and it might be concluded that nature has availed herself of this angle to mark out the diversities of the animal kingdom, and at the same time to establish a scale from the inferior tribes up to the most beautiful forms which are found in the human species. Thus it will be found that the heads of birds display the smallest angle, and that it always becomes of greater extent as the animal approaches more nearly to the human figure. Thus, there is one species of the ape tribe, in which the head has a facial angle of forty-two degrees; in another animal of the same family, which is one of those simiæ most approximating in figure to mankind, the facial angle contains exactly fifty degrees. Next to this is the head of an African negro, which, as well as that of the Kalmuc, forms an angle of seventy degrees; while the angle discovered in the heads of Europeans contains eighty degrees. On this difference of ten degrees in the facial angle, the superior beauty of the European depends; while that high character of sublime beauty, which is so striking in some works of ancient statuary, as in the head of Apollo, and in the Medusa of Sisocles, is given by an angle which amounts to one hundred degrees."

This method was seductive from its exceeding simplicity. Unfortunately, facts were against it, as happens to a good many theories. The curious and interesting discoveries of Prof. Owen have proved beyond dispute, that Camper, as well as other anatomists since him, founded all their observations on orangs of immature age, and that, while the jaws become enlarged, and lengthened with the increase of the maxillary apparatus, and the zygomatic arch is extended, no corresponding increase of the brain takes place. The importance of this difference of age, with respect to the facial angle, is very great in the simiæ. Thus, while Camper, measuring the skull of young apes, has found the facial angle even as much as sixty-four degrees; in reality, it never exceeds, in the most favored specimen, from thirty to thirty-five. Between this figure and the seventy degrees of the negro and Kalmuc, there is too wide a gap to admit of the possibility of Camper's ascending series.

The advocates of phrenological science eagerly espoused the theory of the Dutch savant. They imagined that they could detect a development of instincts corresponding to the rank which the animal occupied in his scale. But even here facts were against them. It was objected that the elephant – not to mention numerous other instances – whose intelligence is incontestably superior to that of the orang, presents a much more acute facial angle than the latter. Even among the ape tribes, the most intelligent, those most susceptible of education, are by no means the highest in Camper's scale.

Besides these great defects, the theory possessed another very weak point. It did not apply to all the varieties of the human species. The races with pyramidal skulls found no place in it. Yet this is a sufficiently striking characteristic.

Camper's theory being refuted, Blumenbach proposed another system. He called his invention norma verticalis, the vertical method. According to him,122 the comparison of the breadth of the head, particularly of the vertex, points out the principal and most strongly marked differences in the general configuration of the cranium. He adds that the whole cranium is susceptible of so many varieties in its form, the parts which contribute more or less to determine the national character displaying such different proportions and directions, that it is impossible to subject all these diversities to the measurement of any lines and angles. In comparing and arranging skulls according to the varieties in their shape, it is preferable to survey them in that method which presents at one view the greatest number of characteristic peculiarities. "The best way of obtaining this end is to place a series of skulls, with the cheek-bones on the same horizontal line, resting on the lower jaws, and then, viewing them from behind, and fixing the eye on the vertex of each, to mark all the varieties in the shape of parts that contribute most to the national character, whether they consist in the direction of the maxillary and malar bones, in the breadth or narrowness of the oval figure presented by the vertex, or in the flattened or vaulted form of the frontal bone."

The results which Blumenbach deduced from this method, were a division of mankind into five grand categories, each of which was again subdivided into a variety of families and types.

This classification, also, is liable to many objections. Like Camper's, it left out several important characteristics. Owen supposed that these objections might be obviated by measuring the basis of the skull instead of the summit. "The relative proportions and extent," says Prichard, "and the peculiarities of formation of the different parts of the cranium, are more fully discovered by this mode of comparison, than by any other." One of the most important results of this method was the discovery of a line of demarcation between man and the anthropoid apes, so distinct, and clearly drawn, that it becomes thenceforward impossible to find between the two genera the connecting link which Camper supposed to exist. It is, indeed, sufficient to cast one glance at the bases of two skulls, one human, and the other that of an orang, to perceive essential and decisive differences. The antero-posterior diameter of the basis of the skull is, in the orang, very much longer than in man. The zygoma is situated in the middle region of the skull, instead of being included, as in all races of men, and even human idiots, in the anterior half of the basis cranii; and it occupies in the basis just one-third part of the entire length of its diameter. Moreover, the position of the great occipital foramen is very different in the two skulls; and this feature is very important, on account of its relations to the general character of structure, and its influence on the habits of the whole being. This foramen, in the human head, is very near the middle of the basis of the skull, or, rather, it is situated immediately behind the middle transverse diameter; while, in the adult chimpantsi, it is placed in the middle of the posterior third part of the basis cranii.123

Owen certainly deserves great credit for his observations, but I should prefer the most recent, as well as ingenious, of cranioscopic systems, that of the learned American, Dr. Morton, which has been adopted by Mr. Carus.124

The substance of this theory is, that individuals are superior in intellect in proportion as their skulls are larger.125 Taking this as the general rule, Dr. Morton and Mr. Carus proceed thereby to demonstrate the difference of races. The question to be decided is, whether all types of the human race have the same craniological development.

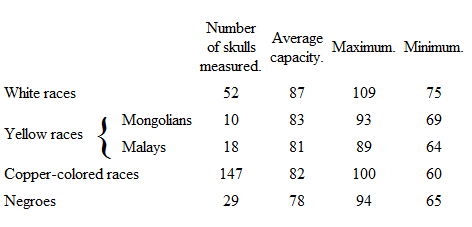

To elucidate this fact, Dr. Morton took a certain number of skulls, belonging to the four principal human families – Whites, Mongolians, Negroes, and North American Indians – and, after carefully closing every aperture, except the foramen magnum, he measured their capacity by filling them with well dried grains of pepper. The results of this measurement are exhibited in the subjoined table.126

The results given in the first two columns are certainly very curious, but to those in the last two I attach little value. These two columns, giving the maximum and minimum capacities, differ so greatly from the second, which shows the average, that they could be of weight only if Mr. Morton had experimented upon a much greater number of skulls, and if he had specified the social position of the individuals to whom they belonged. Thus, for his specimens of the white and copper-colored races, he might select skulls that had belonged to individuals rather above the common herd.127 But the Blacks and Mongolians were not represented by the skulls of their great chiefs and mandarins. This explains why Dr. Morton could ascribe the figure 100 to an aboriginal of America, while the most intelligent Mongolian that he examined did not exceed 93, and is surpassed even by the negro, who reaches 94. Such results are entirely incomplete, fortuitous, and of no scientific value. In questions of this kind, too much care cannot be taken to reject conclusions which are based upon the examination of individualities. I am, therefore, unable to accept the second half of Dr. Morton's calculations.

I am also disposed to doubt one of the details in the other half. The figures 100, 83, and 78, respectively indicating the average capacity of the skull of the white, Mongolian, and negro, follow a clear and evident gradation. But the figures 83, 81, and 82, given for the Mongol, the Malay, and the red-skin, are conflicting; the more so, as Mr. Carus does not hesitate to comprise the Mongols and Malays into one and the same race, and thus unites the figures 83 and 81 – by which he receives, as the average capacity of the yellow race, 82, or the same as that of the red-skins. Wherefore, then, take the figure 82 as the characteristic of a distinct race, and thus create, quite arbitrarily, a fourth great subdivision of our species.