Полная версия

Pesticides and Pollution

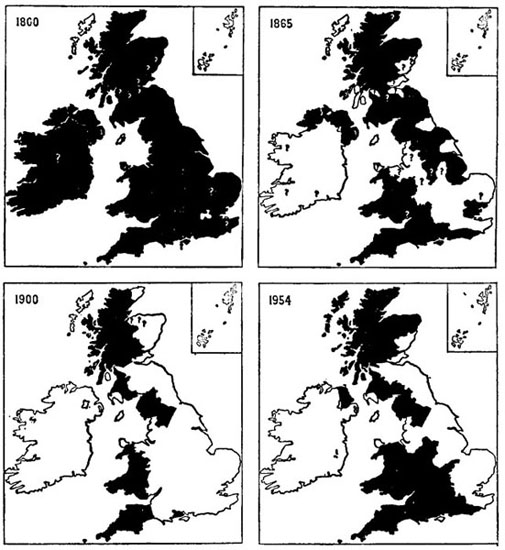

Fig. 1 Changes in the distribution of the buzzard in the British Isles. (from Dr. N. W. Moore with acknowledgement to British Birds).

KEY: Black: Breeding proved, or good circumstantial evidence of breeding.

? on black: Circumstantial evidence suggests that breeding probably took place.

? on white: Inadequate evidence of breeding.

White: No evidence of breeding.

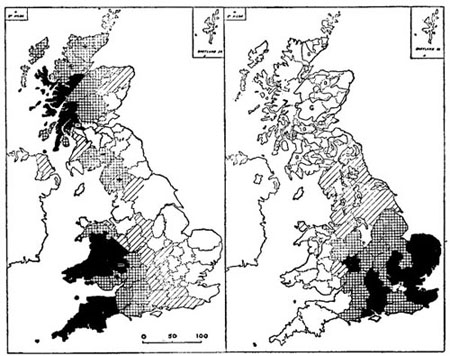

Fig. 2 a. The breeding population of the buzzard in 1954.

KEY: Black: 1 or more pairs per 10 square miles.

Cross-hatch: More than 1 pair per 100 square miles, but less than 1 pair per 10 square miles.

Diagonal hatch: Less than 1 pair per 100 square miles.

White: No breeding buzzards.

+ means that breeding density may belong to the category higher than that indicated.

—means that the breeding density may belong to the category lower than that indicated.

b. Game preservation in 1955.

KEY: Black: 3 to 6 gamekeepers per 100 square miles.

Cross-hatch: 1 to 2 gamekeepers per 100 square miles.

Diagonal hatch: Less than 1 gamekeeper per 100 square miles but more than 1 per 200 square miles.

White: Less than 1 gamekeeper per 200 square miles.

G. Principal grouse-preserving areas. On these, and also on some very large estates, the numbers of keepers may be higher than shown on this map.

Mice and rats invaded man’s home as soon as there was a home to invade. They also lived in his grain stores and farm buildings. Early man tried to make his granaries rodent-proof, sometimes with remarkable success. Control by trapping and poisoning was generally inefficient, and the rodent population in contact with man was roughly a measure of the amount of food he made available. A mouse-proof larder is more effective than an apparently efficient trap. The domestic cat was probably the most useful method of local control, though cats, like other “pesticides,” have had their side effects. Those that have escaped and become feral have important effects on other wild life. Modern methods of rodent control are much improved, but these animals still do much economic damage in our cities and on our farms to-day. It is perhaps surprising that the black rat (Rattus rattus), which is found mainly in towns, where it is particularly at home in hot-water ducts in tall buildings, was our “original rat,” though some think even it only arrived about A.D. 1200, and the brown rat (Rattus norvegicus), which is the species commonly found in the country, only arrived in Britain in the eighteenth century. The black rat was apparently driven from the rural haunts by the brown invader.

Pigeons and sparrows are serious agricultural pests, against which no really satisfactory control measures have so far been devised. Pigeons become more numerous each year. This increase is probably due to the increased amount of winter food, particularly clover leys on farms, that is available. The recent fall in the number of hawks may also have had some effect. Organised shoots give some sport to the participants, but have negligible effects on the pigeon population. Work on poisoning or narcotising pigeons is progressing, but the danger to other and more desirable species of birds is difficult to prevent. Sparrows probably increase because suburban householders feed them in winter. This enables them to survive in cold weather, and the increased population does more harm on the nearby farms to which it migrates in summer and autumn. Again shooting and trapping has little effect.

Farmers and others were then soon aware that wolves and other large mammals and birds might be pests, competing with them in various ways, even if they often overestimated the damage done by the carnivores and sometimes underestimated the amount of food taken by rabbits and other herbivores. They took active, if sometimes misdirected, steps to control these animals. On the other hand, they almost always underestimated the harm done to their crops and to their health by insect pests, and it is only in recent years that serious attempts have been made at control in this direction.

In Britain we do not have plagues of locusts, which in many countries can consume the whole of a crop, but it is estimated that to-day some £300,000,000’s worth of food is lost each year because of pests of crops and insect damage to farm stock. This sum is almost exactly the same as is spent annually on the support of agricultural prices (“farm subsidies”). Some insects, like the caterpillars of Cabbage White butterflies, eat crop plants, reduce the yield and make many plants unsaleable. Other insects do little damage themselves but carry organisms which cause diseases. Thus aphids carry the virus causing virus yellows in sugar beet; this can seriously reduce the value of the crop. For many years farmers and gardeners accepted insect damage as something they could not prevent. They learned by experience that it could sometimes be avoided or reduced to a minimum by timing their operations carefully. Thus if broad beans in the garden are sown early, seed is set before aphids (“black fly”) are numerous and a good crop is obtained, but in two years out of three a late sown crop will be smothered by insects and prove a failure. Cultural devices such as this are valuable and important, but will seldom allow a late crop of broad beans to be produced. Field beans, which flower and set seed over a long period during the summer, cannot be successfully grown in a way to avoid attack in a bad aphid year. Resistant strains of crop plants have been recognised and used for many years, and in future are likely to prove very important, where resistance is linked with high yield and quality. Farmers generally prefer to be able to grow the most profitable crop at the most convenient time and wish to attack pests by any possible means. Before 1939 most effective insecticides (except general poisons very dangerous to man) could only be produced in relatively small quantities and at a price which made their use on many crops uneconomic. The farmers therefore have welcomed the synthetic insecticides which can be produced in unlimited quantities and which, at first at any rate, seemed the perfect answer. The dangers from their use are described in later chapters.

Insect pests of crops were soon recognised as such, even if little was done about the problem until very recently. The importance of insects as vectors of disease has only been understood for about seventy years, though man and his habitations have provided niches for troublesome parasitic species in the same way that wild animals have supported their own parasites. Man has sometimes controlled insects of medical importance effectively without understanding the problem. Malaria was formerly widespread in Britain, but it was almost eliminated long before man knew the parasitic organism concerned or that it was carried only by the Anopheles mosquito. This was because man avoided marshy areas, thinking that malaria was caught from the “bad air,” and so he kept away from the breeding places of the mosquitoes. He also drained the swamps, usually to produce better agricultural land, but in so doing he got rid of the insects which carried the disease. Incidentally naturalists are now very concerned at the continued draining of marshes and swamps, which are now the last refuges of many species of wild life. This is just one of the ways in which non-chemical pest control can have effects which have end results which may be as disastrous to wild life as the most indiscriminate use of chemicals.

In the Middle Ages most people of all ranks of life harboured body lice on their persons, and as recently as 1940 the majority of the girls in our industrial cities had lousy heads. Personal cleanliness could eliminate these pests, except where conditions were grossly overcrowded, but in war and after any disaster infestation, and the risk from louse-borne typhus fever, grew. Persistent insecticides now control these insects, and properly applied to man and his clothing they present little danger to any other organisms.

Pest insects which attack man, but depend on his having a permanent home, include fleas and bedbugs. Fleas are not only a nuisance, but also carry plague, a disease which died out in Britain many years before effective insecticides were discovered to control the vectors. Improved hygienic conditions rather than chemicals have made fleas uncommon insects.

Human bedbugs are very similar to the species which attack bats and swallows, and primitive man may have become infested first when he also lived in caves. Bugs were common from the earliest times in the warmer parts of the world. However, Britain had no bedbugs before the sixteenth century, possibly because the houses were too cold. Bugs certainly existed in Italy in classical times. When bugs arrived in Britain, they soon spread through overcrowded slums, and before the 1939 war most houses in our cities, except detached surburban villas, harboured at least a few. However, they were only common in unhygienic and overcrowded dwellings, and improved conditions soon reduced their numbers. Modern insecticides, particularly those which put a persistent film in the cracks which the bugs haunt, control the insects effectively without seriously contaminating the environment.

When his numbers were few, pollution was not a serious problem to man. Many pests, both plant and animal, have become common only because man has produced suitable conditions. In some cases pests have been controlled with little harm to the environment, in others pest control has become a new and potent form of pollution. The great difficulty is to assess accurately just how much pollution affects the environment and the plants and animals it contains. We are seldom able to give simple answers. Sometimes an animal has obviously been killed, perhaps from the effluent from a factory, perhaps by accidental contamination with a pesticide. Generally, however, we have to depend on circumstantial evidence of damage, and this is the reason for the controversy which so often surrounds our subject.

Toxicology is difficult and complicated. The results of analyses of animals’ bodies, where traces of poisonous substances are found, are not easily interpreted. In the case of well-known poisons like arsenic, strychnine or cyanide the situation may be less mysterious if large amounts are found. We know, for instance, that if a man eats five grams of lead arsenate he is likely to be fatally poisoned. If the pathologist finds ten grams of lead arsenate in the stomach of a corpse, he will be almost certain that this poison caused death. If he finds only a few milligrams, he will be almost certain that death was due to some other cause. The finding of intermediate amounts makes diagnosis difficult. Consideration must be given to the site where the poison is found in the body, and to losses due to vomiting or excretion. The situation is even more complicated where poisons are broken down in the body, either as part of the process of damaging the victim, or due to post mortem changes. If we do not know accurately how toxic a chemical is to a particular animal, and if we are not fully familiar with these chemical changes, we cannot usually say for certain whether a small residue of poison in a live or dead specimen has any significance.

It is generally fairly easy to establish the acute toxicity of a substance, that is the amount which, in a single dose, is lethal. Experiments with rats, chicks or fish are commonly made. Groups of animals are given different doses, and the least amount of poison which kills is found. Usually different individuals of a species show a somewhat varied susceptibility, and instead of determining the amount which kills them all, the so-called LD50, that is the amount which kills half of a batch, is determined. In most instances few animals die from a single dose of half the LD50, and twice the LD50 is likely to kill almost every individual. However, this is not always the case. Sometimes a population contains a few individuals which can survive relatively large doses of certain poisons; under certain circumstances these may be selected out and may breed a strain which is more resistant than the normal to a toxic substance. Resistance or susceptibility to poisons is not necessarily correlated with unusual or subnormal “vigour,” and this type of chemical selection may leave a species less well adapted to normal environmental conditions.

Although acute toxicity is not difficult to determine in the laboratory, it can only be done with a limited number of species, and values for others (including man) can usually only be inferred. Also the effects of a specific poison may differ even with the same batch of the same species depending on how it is administered, e.g. neat, in suspension, in oily solution, on an empty stomach, through the skin, by inhalation and so forth. These difficulties have usually meant that, at least where man is exposed, a fairly large “safety factor” has been applied. Thus if work with rats suggests that the LD50 for substance “X” is 50 milligrams per kilogram, it could be assumed that half of a group of 50 kilogram men would probably die if they ate one gram each of “X.” It would generally be found that a single dose of one hundredth of this amount, i.e. of 10 milligrams, would be unlikely to be harmful. In many cases this assumption is quite justified but contamination of food to this extent would not normally be tolerated.

While there are sometimes difficulties in establishing the effects of single, large doses of poisonous substances, the study of the effects of repeated small doses, each of which would probably be harmless, spread over long periods, presents even more serious problems. Poisons which are unstable are unlikely to be very dangerous under these circumstances. Those which are stable, particularly if they are stored in the body, may present great risks even if they are not acutely poisonous in single doses. All these factors are borne in mind when, for instance, new insecticides are tested. Their action on a number of insects, particularly pests, is determined. Then long-term experiments, lasting over severa, years and a number of generations, are then made with rats, chickens and other animals. It is obviously impossible to include more than a few species in such trials, so it is not surprising that sometimes a desirable species of bird, or mammal, is found (too late) to be unexpectedly susceptible. The effects of chronic exposure to low-level industrial and urban pollution is even harder to study. Some, impressed by the complexity of the situation, fear that the ecological effects of pesticides may bear little relation to their gross toxicity.

Everyone wishes to abolish the damage which may be caused to man and to wild life by pollution from every source. As, however, we are not always agreed as to when damage is being caused, or how exactly some obvious damage arose, an easy solution will not be found. Man has always polluted his environment; he has always suffered from pests, but because of the “population explosion,” these problems have become more serious in recent years. The need for more research in these subjects is obvious, if irreparable damage to wild life, and to man, is to be avoided. Equally important, we must make sure that the results of such research are quickly and efficiently applied.

CHAPTER TWO AIR POLLUTION

Perhaps the most obvious way in which man has contaminated his environment is by polluting the air with smoke and with the waste products from industry. Everyone has seen the pall of smoke hanging over a city. He knows that many plants and animals are not found in the middle of a city. It is, however, difficult to find exactly how this pollution has affected wild life, notwithstanding much intensive study of the subject. Although some lichens and other plants seem to be particularly susceptible to the effects of atmospheric pollution, and their distribution may be correlated with it, nevertheless the position is far from simple. This is perhaps not surprising, as we seldom have a constant amount of any noxious substance in the air at any place over any long period of time. The smoke emitted from a domestic fire or from a factory is in bursts followed by periods of comparative inactivity; in some towns factories are only allowed to give out black smoke for five minutes in an hour. The weather has a profound effect; calm clear periods, particularly when temperature conditions prevent upward circulation, allow the pollution to concentrate, while strong winds ventilate the area though they carry the substances in detectable amounts to distant parts of the country.

As soon as man discovered fire, he made smoke and so polluted the atmosphere. The effects were local and slight until about the thirteenth century, when coal fires in cities were found to produce winter fog and punitive laws were introduced, apparently with little permanent effect. As cities were small, and little coal was burned, probably no great damage was done except perhaps to men themselves living in unventilated houses. When cities grew, smoke became, and still is, a major problem.

Industrial development in the nineteenth century was accompanied by new types of pollution. Hydrochloric acid gas from alkali works caused a public outcry, with resulting legislation. Attempts have since been made to restrict all the emissions from factories to a “safe” level. This happened none too soon. Much of the gross pollution accompanying the dereliction in areas like the lower Swansea Valley was airborne from factories in the area.

The results of atmospheric pollution differ in an interesting way from those of insecticides which are discussed in later chapters. Man himself has been the major victim of polluted air; insecticides have had serious effects on wild life, but man has seldom been injured by the direct effect of these substances. The ecological significance of this difference is discussed in later chapters.

Every urban housewife is only too well aware of the reality of atmospheric pollution. Curtains and furnishings remain clean for months or years in the country; in the towns they are grimy in a matter of days. Students of pathology who have only seen inside the corpses of city-dwellers are amazed, and think they have found some new disease, when they see for the first time the healthy red lungs of a farm worker who has never lived in or near a town. Walkers on the moors of the Peak District know that their clothes will be blackened if they sit on the heather, and most flocks of sheep there, except immediately after shearing, seem to consist only of black sheep. The Peak District sheep on moors surrounded by industrial towns contrast with the much whiter animals found in the remoter highlands of Scotland, and this colour difference has been suggested as a rough and ready means of estimating pollution.

Air pollution in Britain to-day is mainly due to burning coal and oil. Local effects from many chemical processes, and petrol and from diesel engines also make their contribution. Perhaps the most serious chemical problem is due to fluorine, mainly from brick works, and this is specially mentioned below. Legislation and regulations have reduced the amount of many pollutions to such an extent that wild life is usually not seriously harmed, except in particular danger areas, but the amounts of dust, smoke and sulphur dioxide produced from fuel are so enormous and so unaesthetic that they cannot be ignored.

Britain consumes annually about 200,000,000 tons of coal and 25,000,000 tons of fuel oil. The output of noxious products is estimated at 1,000,000 tons of dust, 2,000,000 tons of smoke and over 5,000,000 tons of sulphur dioxide. Coal produces relatively more smoke and dust, and oil more sulphur dioxide. This pollution is obviously very unevenly spread over the country. The Ministry of Technology, formerly the Department of Scientific and Industrial Research, compiles reports from some 2,111 recording instruments spread all over Britain. These show that in heavily industrialised areas over 1,000 tons of grit and dust must fall on each square mile in a year; this corresponds to about two pounds on each square yard. In cities generally the figure is in the region of a quarter of a pound, and in rural districts it may be less than a tenth of an ounce. Sulphur dioxide, being a gas, is dispersed more readily, and the rural concentration is probably about a tenth of the urban or industrial figure, though under unfavourable conditions much higher values may be obtained adjacent to some factories. The housewife knows that polished silver or copper tarnishes more quickly in the town than in the country; this is correlated with the SO2 in the air.

The effects of industrial pollution on man have been studied intensively, but with somewhat confusing results. It is believed that the four-day “smog” in December, 1952, killed some 4,000 Londoners. Exactly how smog, which is looked on as a brand of fog containing more contaminants and smaller and more penetrating particles, kills is not understood. It may act as a general irritant which acts as the “last straw” in the weak and those with respiratory trouble. It has been suggested that the excess of free sulphuric acid is the lethal factor, but total amounts are small (only 0·05 parts per million as a maximum) and this view is not generally accepted. There is no doubt that smog is a killer, and it kills other animals than man if they are exposed (many cattle died at the 1957 Smithfield Show), but fortunately it does not often spread outside our largest cities. Mist, which consists of relatively clean water particles, is of course widespread. Fog, which is essentially mist containing amounts of smoke, penetrates some distance from industrial areas, but seems to have comparatively little acute effect on man or animals.

Acute effects on man and animals of smog, and possibly of fog, can be shown to occur even if they cannot be fully explained. Chronic effects of the usual urban levels of pollution no doubt occur, but are not so easily demonstrated. Lung cancer is higher in cities than in the country, but we do not know the precise cause. Respiratory diseases are similarly commonest in industrial areas. Although we ourselves filter the air we breathe and reject much of the dirt, city dwellers’ lungs are impregnated with dirt particles, and it is difficult to feel sure that this is not harmful. For these reasons considerable efforts are being made to reduce atmospheric pollution. “Smoke-free” zones have been scheduled in most cities, and some progress is being slowly achieved to reduce the smoke and dust. Fogs and smogs are less serious than they were, though the amount of sulphur dioxide in the air is less easily controlled and tends to increase even in smoke-free zones.

Farmers near to cities suffer from the effects of smoke and grime. It has been estimated that pollution, by damaging pastures in particular, costs the East Lancashire farmers over two and a half million pounds a year. Horticulturalists find that smoke reduces light intensity indoors and out, and obscures the glass of greenhouses, covering them with deposits which are difficult and costly to remove.

Smoke, by reducing light intensity, will obviously retard plant growth, and may encourage some species at the expense of others, though there seems remarkably little evidence of this happening except in industrial areas. Many city gardens do indeed suffer from the lack of light, but this is not due to pollution so much as to shading from buildings, and, more particularly, from trees. The luxuriant growth on bomb sites was a revelation to many. Here shading from buildings and trees was reduced to a minimum. Often one finds that spring flowers do quite well, before the trees are in leaf. In the confined space of a small city garden we may prefer trees to flowers, but we can seldom have both.