Полная версия

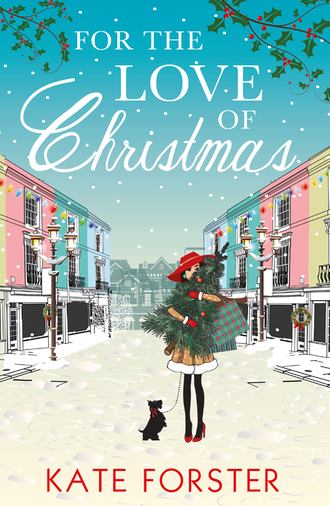

For the Love of Christmas

Rebecca’s so-called splendid life isn’t so wonderful. She is fresh out of rehab, her husband and children aren’t home for the holiday, and her Christmas tree has alopecia.

Days from Christmas, Rebecca has to explore her grief about a loss so huge it tipped her over the edge, and imagine a future that may be spent alone.

But, she learns, Christmas for one is possible. It’s just a lot nicer when there’s family to share it with.

Love, loss and forgiveness come together to make a Christmas that Rebecca will never forget, and one that will unwrap a joyous future, even if it’s not at all like what she imagined was waiting for her under the Christmas tree.

For the Love of Christmas

Kate Forster

www.mirabooks.co.uk

KATE FORSTER

Kate lives in Melbourne, Australia with her husband, two children and two dogs, and can be found nursing a laptop, surrounded by magazines and watching trash TV or French films.

Contents

Cover

Blurb

Title Page

Author Bio

Story

Extract

Copyright

Rebecca

Rebecca Swanson sat in the back of the taxi, taking one leather glove off her slender hand, then sliding it back on again. She liked the firmness of the quality leather that cocooned her fingers, as they nestled in the inner cashmere lining.

‘Home for Christmas?’ asked the cabbie cheerfully, glancing at her in the rear-view mirror.

‘Yes,’ Rebecca said, with the half smile usually reserved for people who asked too many questions. The business press saw it often but the cabbie didn’t seem to pick up on the nuance.

‘Staying with family?’

Was she?

She had no idea since no one was waiting for her at the airport.

She had hoped to see Jamie there, with Oscar and Sofie by his side, maybe with a bouquet of flowers in his arms. White lilies and a few red poinsettia branches interspersed, as an acknowledgement of her two favourite things: Christmas, and the colour red.

Instead there was a lonely arrival at busy Gatwick. Her fellow travellers from Denver all seemed to know someone, as they waved and hugged people who waited by the barriers.

It was only on this flight that she saw how far she had come, and not just geographically. Each round had been hard fought, each awakening like a punch to her heart, but what she was about to face would put everything she had learned to the ultimate test.

Sofie and Oscar’s faces came into her mind and her stomach clenched both mutual fear and nerves.

How could they ever forgive her?

‘They will forgive you when you forgive yourself,’ a voice in her head said calmly.

When will that happen?’

‘When you’re ready, you’ll know it,’ the voice stated ambiguously.

Stupid voices in her head, she thought. For years they had been saying other things, encouraging her instead of telling her to stop. Making allowances for her behaviour, and always lying to her.

‘Done your shopping yet?’ the cabbie asked.

She didn’t know which voice was more annoying.

Rebecca closed her eyes and leaned her head against the seat.

‘Not yet,’ she answered.

There hadn’t been any time to buy anything in Denver, and there certainly wasn’t anything in the gift shop of Arrow Lodge, where she’d stayed for the last eight weeks. She didn’t want any memories of the time spent there; it wasn’t a place to celebrate with a keepsake.

‘Better get to it,’ he said. ‘Only five days till Christmas.’

Please don’t sing, she thought, as he broke into song.

‘On the first day of Christmas, my true love gave to me …’

She stared out of the window. Gifts were easy to come by, and as the CEO of the biggest online luxury store in Europe, she could have ordered anything, and had it delivered; wrapped with red grosgrain ribbon, and under the tree on the same day.

Except she couldn’t make phone calls to anyone who wasn’t on the list when she was away, and the last people she felt like talking to were people at work. Surely the gossip was running hot with the news their CEO was on leave for eight weeks.

‘Where did you travel from, love?’ The cabbie’s voice broke through her dark thoughts.

‘Colorado,’ she answered, too tired to think of a lie.

‘I read that the whacky baccy is legal there now,’ he said.

‘Sorry?’

‘The marijuana.’ He said the word slowly, stretching it into five syllables.

‘I believe so, yes,’ she answered, not because she knew that much but because it seemed like he wanted her to know.

‘Did you partake of the ganja?’ he asked and Rebecca wondered how many names he knew for the legal herb.

‘No,’ she snapped, and the cabbie was silenced.

She wished she could have felt more shame at her rudeness but the cab was edging closer to home and Jamie and the children would be waiting. She had to be prepared.

The shop windows became more decorative and beautiful the closer they got to Notting Hill.

This was the time of the year she would put the beautiful red wreath on the door, made of red velvet oak leaves, and she crossed her gloved fingers that Jamie knew where to find it in the attic.

The cab slowed down as they turned into her street. ‘Just past the green Citroen,’ she said, pointing to her neighbour’s car.

The first thing she noticed when the cab came to a standstill was that the door was wreathless. Then she saw there were no clumsily cut snowflakes taped to the windows. And finally she saw that there was no welcome home party at the door.

No words on computer paper taped across the door, just some mail sticking out of the letterbox.

‘Here you are,’ said the cabbie stiffly and she regretted being impatient with him earlier.

‘Thank you,’ said Rebecca as she handed him his fare and a generous tip, enough to encourage him to help her with her large suitcases.

Mollified, he got out of the car.

‘Must be nice to be home,’ he said, as he heaved a case from the boot of the car.

‘It is, actually,’ she said, telling the truth.

‘You were away a while, then?’

‘Eight weeks,’ she answered.

‘That’s a while. What were you doing away for that long? Work, was it?’

He was heaving her case up the stairs now, so she felt she owed him something. A nugget to share with the next fare.

‘I was ill,’ she said. ‘I went for specialised treatment.’

His eyes opened wide and he almost gasped.

‘You better now, then? Is that why you’re home?’

She smiled, realising he needed her to be well, even though they didn’t know anything about each other.

‘I’m getting there,’ she said, with more hope than she felt.

She felt for her long-unused house keys in her handbag, and put the largest one in the door.

The click of the lock sounded so familiar, she thought she would cry.

Maybe this was a dream, and she was coming home from work, with plans to decorate the house before the children and Jamie came home. She would make a roast chicken and salad for dinner, and their life would be a better version of what it was before.

‘Good luck, look after yourself,’ the cabbie called as he went back to his car.

‘Thank you,’ she said, giving him a little wave before she dragged the cases inside.

Closing the door, she leaned against it and breathed in the scent of her home. She had made it, she thought, and gave herself a mental pat on the back.

‘Hello?’ she called, knowing no one was home but hoping all the same.

Nothing came back in return and she pulled her phone from her bag and dialled a number. She waited while the line connected across the continents.

‘Rose-Marie, it’s Bec, I’m home.’

‘Welcome home,’ said the instantly soothing American accent. ‘How are things?’

‘Lonely,’ Rebecca answered, feeling her eyes burning with tears. ‘No one is here. I don’t think they have been here for weeks.’

‘Did Jamie say he would meet you at the airport?’ asked Rose-Marie.

‘No, I just assumed. I left him a voice message with my arrival dates.’

‘Never assume,’ said Rose-Marie. ‘Ask for what you need. If you wanted him to pick you up, you should have said that.’

Rebecca swallowed her tears.

‘And the red wreath isn’t up on the front door,’ she said. ‘That always means it’s Christmas to me.’

‘You can put it up,’ said Rose-Marie, and Rebecca heard the smile in her voice.

‘I know you think I’m ridiculous,’ she said.

‘No, I think you’re facing the unknown, and it’s frightening as things aren’t like they used to be.’

Rebecca sat on the uncomfortable Danish chair that Jamie had bought last year. It was supposed to be a design classic but she felt the only thing it was designed for was a backache.

But right now it felt good to have physical pain to accompany her emotional anguish.

‘Have a sleep, a shower and then call me when you speak to Jamie,’ Rose-Marie said gently.

‘Okay,’ she answered, feeling like a child.

She placed the phone down on the glass coffee table that Jamie had bought years ago, when Sofie was born.

That table had caused her so much worry, she thought, as she ran her fingers over the sharp edges.

Each step Sofie had taken as a toddler was accompanied with ‘Mind the table’, until Jamie had renamed it the Mindthetable Table.

Rebecca stared at it and then stood up, and went and opened the front door.

Walking back to the Mindthetable Table, she lifted the art and architecture books from the glass and placed them on the floor. Next she took the set of sweet little enamel boxes with mother of pearl inlay and placed them on top of the books.

Bracing herself, she bent her knees and lifted the monstrosity.

‘Gawd,’ she wheezed, almost buckling under the weight.

Tottering like Sofie once had around the table, she inched her way out of the room, and then down the hall and out the front door.

The stairs were precarious but she managed to get it out and down onto the street by the force of sheer hatred for the thing.

‘Goodbye,’ she sneered at the table.

‘Excuse me, are you throwing that out?’ said a voice behind her, and she turned to see a cooler, younger version of Jamie.

‘I am indeed,’ she said firmly.

‘Is it real or a replica?’ he asked carefully.

‘Real,’ she said with a smile, and he glanced at her home, and her lovely camel coat, and nodded.

‘Would you mind if I took it off your hands?’ he asked eagerly.

‘Not at all,’ she said with a smile. ‘In fact, there’s a chair you might like as well.’

Fifteen minutes later, the chair and the table were gone and Rebecca felt extraordinarily happy with her decision, just as Jamie probably felt the same about his. If he didn’t want to live here, then he wouldn’t miss his stupid furniture, she thought, knowing she was being petulant but unable to stop herself.

The voice of Rose-Marie rang in her head: ‘If there is anything in your life you don’t like, then change it. It’s simple. Nothing changes, if nothing changes.’

She walked through the house. The dining room had a thin film of dust on the table, and one of the sideboard cupboards was ajar.

Moving to close it, she felt a familiar trepidation that she hadn’t experienced for the past two months.

Herein lies my problem, she thought as she opened it.

It was empty.

She was grateful to Jamie for at least having the foresight to clear it out before she came home, but shame filled her body and her cheeks burned with memories.

This is what you get when you leave rehab, she reminded herself. A wreathless, alcohol-free, deserted family home.

The tears threatened to fall again and she blinked them away.

There was one thing she could change on that list, she thought, and shrugging off her coat, forgetting her jet lag and suitcases waiting to be unpacked, she climbed the three flights of stairs to the attic.

The box of Christmas decorations was light compared to the table she had just disposed of, she thought, as she carried it downstairs to the living room.

The wreath was on top, wrapped in tissue paper to deter dust and moths, and as she carefully unwrapped it, she gently wiped off some imaginary specks of last Christmas.

‘Hello,’ she said to the wreath.

Taking it by the red velvet ribbon, she opened the front door, and found the nail near the top.

She hung it as though it were a priceless painting, straightening, fussing until she was sure it was sitting beautifully.

She stepped back and smiled.

‘Merry Christmas,’ she said to the wreath and, most of all, to herself.

She might be alone but she wouldn’t let that stop her from having her own special Christmas. She might even make some shortbread or even some strong coloured popcorn because she’d always wanted to do that and never had the time.

This was the start of the new Rebecca Swanson: recovering alcoholic, mother, wife – perhaps soon to be an ex-wife, she thought – CEO and, above everything else, a Christmas addict.

Jamie

‘Where is it, Sofie?’ Jamie demanded, trying to keep the anger from his voice.

His temper was part of the problem, Rose-Marie had said during one of their Skype therapy sessions.

‘You fly off the handle so easily, it’s exhausting to live with,’ Rebecca had remarked.

‘So that’s why you drink? Because of me?’ he had said in return, even though he knew it was unfair, and that he was really just deflecting the attention away from himself.

He was stressed, and worried about everything. The last year had felt like life was creeping up on him, about to give him a terrible surprise.

And then Rebecca fell down the stairs.

She lay for two hours until the children and their nanny found her and called an ambulance, and that’s when they finally accepted that her drinking was not just a sometime thing.

‘Come on Sof,’ Jamie coaxed. ‘You were the last to have my phone. I need to check if Mummy has called.’

The mention of Mummy swayed her enough to spill her secret and she looked down at her pink-socked feet. ‘I dropped it,’ she said in a half whisper.

‘Dropped it where, darling?’ asked Jamie in a quiet voice.

‘Rain, not thunder, helps the flowers grow,’ Rose-Marie’s voice rang in his head.

Bloody Rose-Marie and her bumper-sticker sayings, he thought. They resounded in his head like old school songs.

Oscar came rushing inside, a gale of freezing wind making the fire in the grate shudder in protest.

‘I think it’s going to snow,’ he announced.

‘I hope not,’ said Jamie. ‘We have to go back tomorrow.’

He returned his attention to his daughter, who at seven looked like an angel but had the wiles of a teenager.

‘Where did you drop it, Sofie?’ He was a little sterner now.

Sofie looked up and widened her eyes, a tactic she had learned from Rebecca, and he felt himself fill with love for both the females in his life.

‘In the bath,’ she said, her voice quivering as she spoke.

‘In the bath?’ he repeated, as though trying to make sense of the words. ‘In the water?’

She nodded.

‘Why did you have my phone in the bath?’

‘I was watching Taylor Swift videos,’ she said with a slight eye-roll, as though he knew nothing about anything.

‘And you dropped it in the water, and then didn’t tell me for the past day, even though you have seen me frantically looking?’ He felt his temper rising.

Rain, rain, less thunder, he reminded himself.

‘Go and get it,’ he instructed.

Oscar, who was twelve and so considered himself wise beyond his height, was lying on the sofa, flicking through a gaming magazine.

‘It’s screwed now,’ he offered.

‘Don’t say screwed,’ said Jamie crossly.

‘Buggered then,’ Oscar said.

Jamie left it alone. At twelve Oscar knew too much about life, electronics, and the truth about his mother.

Sofie was back, holding out the phone to Jamie.

He turned it on and off but nothing happened.

‘You could put it in a bag of rice; that might soak up some of the water, but I doubt it, since it’s been left wet for so long,’ Oscar offered.

Jamie went to the cupboard of the farmhouse he’d rented to try and get to know his children for a few weeks while Bec was in treatment.

Two weeks had felt like a long time when he booked it; now it felt like an eternity.

‘We don’t have any rice,’ he said, as he peered through the staple items. ‘Can I do flour?’

‘No,’ said Oscar, not looking up from his magazine.

‘Pasta?’

‘No,’ came the same answer.

Jamie stood facing the pantry with its jars of mixed herbs and lack of rice and felt himself wanting to cry.

How ridiculous was he? he asked himself.

He missed Bec so much it hurt. He wanted to go and tell her every single thing she had done that was amazing, how the mere presence of her lit up the room, and how he didn’t know how to do things as well as her, certainly not Christmas.

He knew he was too focused on having things perfect, even if they cost him comfort or enjoyment. Like that stupid chair he had bought that every interior designer said was a staple for a true aesthete’s home.

Except it felt how he imagined a medieval torture chair would have done in the dark ages.

No support to the back, no give in the leather, just clean lines.

He had wanted to admit to Bec that he’d made a mistake, but they’d fought so hard about having it inside, he didn’t want to admit that she was right.

Why? he wondered now. Bec was often more right than him, so why had he stopped listening?

‘I’m sorry, Daddy,’ Sofie’s voice came from behind.

‘I know you didn’t mean to drop my phone in the bath but I wish you’d told me straightaway,’ he said, kneeling to look her straight in the eye.

‘I was scared,’ she said, and he felt his heart jerk because he knew it was true. He could be vile, especially when he was angry.

‘I understand,’ he said and bent down to Sofie’s eye level. ‘You have to tell me things and I will promise not to be scary if I’m upset, okay? Can we make a pact?’

Sofie nodded and he could see the relief in her eyes.

‘Tomorrow we will go into the village and see if I can get a new phone,’ he said, standing up. ‘Oscar, can I borrow your phone?’

‘No, you told me not to bring it,’ he said.

‘I didn’t think you’d actually listen,’ said Jamie, shaking his head.

‘I didn’t want you to yell,’ said Oscar, looking up briefly at his father.

Jamie felt sufficiently told off by both his children, and went upstairs to his bedroom, whacking his head on the beams of the farmhouse.

Stupid beams, he thought as he rubbed his head. Who was the landlord? Miss Tiggywinkle?

He lay on the bed and tried to remember the dates for Bec’s return. He had a whole thing planned for the airport, with a sign, and he would wear a chauffeur’s cap, and there would be flowers, white lilies and holly, he had decided.

It was five days until Christmas, he’d reasoned; he had plenty of time. He was sure she’d said she would be back the week before; he was absolutely positive, wasn’t he?

Number one priority: he had to get a new phone.

Sofie

Sofie lay in bed and thought about the three things she loved the most in the world.

Taylor Swift.

Bubbles, her dog.

And her mother.

And not one of them was with her.

Taylor didn’t even know who she was, even though she had written to her a thousand times. She had liked every video on YouTube, and had even written to Katy Perry to ask her to stop bullying Taylor, because everyone knows bullies are the worst kinds of people.

Bubbles was in a kennel, because Dad had said he was too much for the farmhouse, and that he would chase the sheep, but she doubted that he would. Bubbles had excellent manners.

And her mum was in America. She knew she wasn’t there for work, or the knee replacement or whatever lie she had been told by someone. What grown-ups needed to realise about telling lies is that if you decide on a story, you need to stick to it, not have different versions.

Only Oscar told her the truth. ‘Mum’s gone to a place where they tell her to stop drinking,’ he said.

‘Why doesn’t she stay at home and we can tell her?’ asked Sofie.

Oscar had shook his head. ‘Doesn’t work like that,’ he said wisely.

‘So how does it work?’ she asked.

‘I don’t exactly know, but not like that,’ he said, seeming less wise.

She wished she were at home, where her mum would have put up all the decorations and there was a real tree in the living room and new presents appearing underneath it every afternoon, as though by magic, all wrapped beautifully by her mum.

Her mum loved to wrap presents. She would make a real thing of it, with all sorts of pretty paper and ribbons, and perfect folding. Sometimes Sofie would help her, and even though it was never as good as her mum’s, she would still be praised for her work.

She wondered what Taylor was doing right now. Maybe singing or dancing or having her friends over. And Bubbles? He was probably in a cold kennel, with no friends or even a blanket for comfort.

Her eyes filled with tears, as she lay in the dark, unfamiliar room.

And her mum? She was in a hospital, Oscar said. Was she in bed? In a gown with ties on the back like they show in the movies? Was she even alive? Dad didn’t talk about her much any more. Sometimes she spoke to her in her head, but sometimes she didn’t want to because, if she started to tell her mum how sad she was, she thought she would never stop crying.

She closed her eyes and thought about going home. She would walk up the path with Oscar and there, on the front door, would be the red wreath. This was the first sign that Christmas was coming in their house. Dad hadn’t put up anything Christmassy in the house, saying it was a waste of money and they would do it all when they got home.

But Sofie had other ideas and, turning on the small lamp by her bed, she opened the drawer in the little table the lamp sat on and took out the folded pieces of paper and a pair of scissors. She started her nightly routine of cutting and twisting and turning the paper as she worked.

She had sixteen snowflakes so far. She wanted to make thirty-nine, one for each year of her mummy’s life. She planned to stick them on every window downstairs, so it was a wallpaper of snowflakes in the house. She had a lot of work to do, she thought and sighed simultaneously, and settled in to her task for the night.

Oscar

Oscar lay in bed under the covers, playing with his phone. There was no way he was going to give it to his dad; his dad would never give it back, like the time he loaned him his favourite video game to show someone at work, and forgot to bring it home.

Oscar asked so many times, and Jamie promised so many times, that eventually he just asked his mum to buy him a new one.

His dad was unreliable and a bit hopeless, he had decided last year.

And letting Sofie take the phone into the bath – well, that was just dumb. Even he could have told him that but his dad never listened to him. His dad didn’t listen to anyone.