Полная версия

50 shades of teal management: practical cases

Slow problem solving

Meanwhile, the organization’s real problems begin to get solved more and more slowly. After experiencing an inappropriate reaction from their managers, subordinates share information about new problems less and less frequently with the higher-ups, while lacking the necessary privileges and resource to solve them at lower levels. What’s more, due to the fear of having the dogs set on them, information starts to transform in order to protect the person sharing it – or, when such shielding is impossible, it gets completely stuck without ever reaching the boss. Interestingly, decisions traveling in the opposite direction experience their own losses as well. I conducted an analysis which showed that in transitioning from one level of management to another, around 30% of information gets lost. This means that if only 70% of information remains when an order gets to your direct subordinates, then in transmitting this order to the next level of management, you have to take 70% of these 70%: 0.7 × 0.7 = 0.49 = 49%, or less than half! Unfortunately, the information doesn’t merely get lost, but also gets twisted: this means that the remaining 51% is filled with something else, often contradictory to your thoughts, words and desires.

Task 3

Multiply this 0.7 by as many layers of hierarchy there are underneath you, and understand how little of what you say gets through to those who will have to directly carry out your orders, and how much distortion is introduced in the process.

Is it clear now why nothing ever happens the way that you planned it?

Now let’s look at the situation from the client’s side, who has encountered some insignificant, minor problem and lets your subordinate know about it. Your subordinate can’t solve the issue themselves and escalates it higher – what else can they do, when that’s always how they act? But the problem isn’t critical, you have more important and urgent tasks, and as a result, you put it off over and over again until at the end of the day you simply forget about it altogether. Then the exact same client runs into the exact same problem half a year later and understands that nobody even tried to take care of him. They tell the exact same employee, now with some surprise, that the problem could have been solved over all of this time. Your subordinate justifies their behavior, saying that they passed the client’s wishes along to their bosses and assures them that they’ll bring up the issue again. But even if they do exactly that, the result will be the same: you just won’t get around to it. And after some time, the exact same client will run into the aforementioned problem. Now put yourself in that client’s position: it’s not hard to imagine what they think about your company and its attitude toward its customers…

Demotivation of rank-and-file employees

All this time, your subordinates find themselves in a very unpleasant position of being wrongly accused. If they report up, then they can be turned into a sacrificial lamb; if they conceal the information, they can be asked at any moment why such a problem exists, but nobody knows about it. As a result, the poor fellow is in a constant state of stress, and even if their manager still had some power to influence the situation, then the subordinate will only lose motivation, stuck in a position of dependency.

What happens as a result? We hire specialists to work on motivating our personnel and pay them salaries, but in actuality, everything that they concoct doesn’t work for long. There’s some mysterious important reason that demotivates people within the framework of a traditional management system. This reason is learned helplessness. We’ll talk in more detail about this reason in the fourth chapter. Now I’ll just say that the essence of this phenomenon comes down to the following: if we take an employee’s rights away, but nevertheless continue to ask as much of them as before, they will start fearing responsibility of any kind and begin to avoid it by any means necessary. This gives a person who is extremely demotivated and dodges responsibility as best they can, lacking any desire to make decisions. Meanwhile, it’s very important to understand that we are the ones who made them that way. After all, in everyday life outside the workplace, everything in this person’s life is the polar opposite: they take responsibility for where they live and what they eat – and if they have children, they’re responsible for their lives, too! So why in the world do they turn out to be "insufficiently responsible" to be worthy of the permissions necessary to make the simplest decisions for the company?

Mass irresponsibility

What’s going on inside the organization? Both managers and their subordinates are becoming hostages of a system of management under which it’s best not to be responsible for anything at all. This became the reason for an unbelievable dearth of good managers, despite a surfeit of qualified specialists. After all, who would be clamoring to take on additional responsibility for other people, too? In such a situation, those who are solely interested in career growth and power begin to flourish. As a result, the situation gets even more complicated: after all, such people consciously surround themselves with others who can’t compete with them and intentionally inflate their staff numbers to seem like more significant managers.

Meanwhile, other employees initially protest at the sight of such phenomena but then, when they understand that their concerns are not being heard, they also begin to lose responsibility, asking themselves, “What, do we really need this? Why should the buck stop here?” They pass the requirement to figure problems out onto their supervisors, who ultimately have no time to do so, since they’re already so busy in the first place…

“Wars” between divisions

Twilight zone of rights and responsibilities — this is a zone between two or more divisions, where nobody in any division has the necessary rights to solve the problems that inevitably arise – and nobody wants to take on the responsibility for doing so.

In a situation where nobody wants to take responsibility, “wars” unavoidably begin to brew between departments and divisions, which also has a negative influence on the overall results of the company’s work. For that matter, it is the divisions that have to work most closely together in order to achieve their common goals that fight the most often! It’s not hard to guess that the reason also lies in the management system.

Everything usually begins with a problem that arises in the twilight zone of rights and responsibilities of two or more divisions – which is where nobody has the necessary rights to solve the problems that inevitably arise – and nobody wants to take on the responsibility for doing so. Otherwise, it would not have become a problem in the first place; it would simply be another task that each of the divisions successfully solves every day. By the way, the most common situation is when the problem at hand arises due to a lack of communication between these divisions: someone didn’t warn someone else, or else they didn’t hear or understand – or merely understood incorrectly. By itself, this is nothing to worry about. The issue is that when the problem arises, nobody is in any rush to solve it. Everyone thinks to themselves, “That’s not my responsibility. We have enough tasks on our own; we won’t have time to do everything otherwise!”

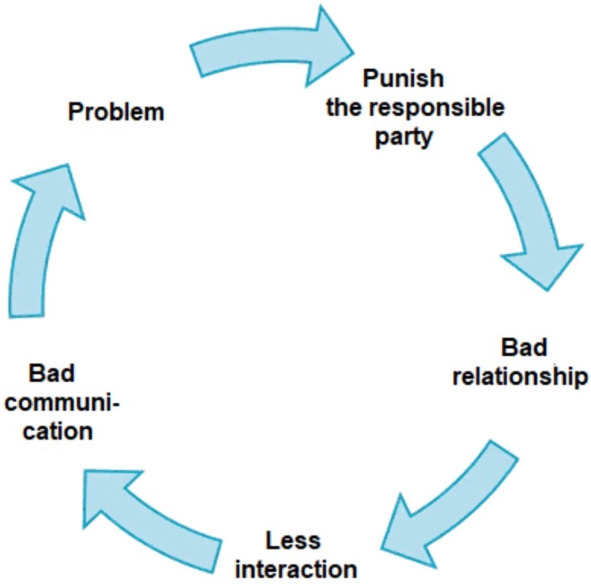

But when nobody solves the problem, it begins to grow, and ultimately ends up becoming so enormous that the big boss at the top of the food chain can see it. Of course, any manager in such a situation has one universal solution: delegate the responsibility to someone. However, regardless of which of these divisions has its representative chosen as the responsible party, they will think that they were unfairly punished in favor of their colleagues from the other department (s). As a result, relationships between employees of these divisions grow worse; they begin to communicate less frequently, and the situation only continues to spin out of control. A vicious cycle is created, which I have drawn out in the diagram below.

Problems begin to appear left and right out of this twilight zone between departments as though from a horn of plenty, even though everything was just fine not long ago. Management gradually begins to distribute responsibility in a decidedly random manner, "rewarding" choice employees without asking whether they have the necessary rights to carry out this responsibility. Alas, some tasks can only be completed in collaboration.

Ultimately, the employees in these warring departments develop prejudices and they begin to assess the situation in a biased manner. It gets to the point that they begin to earnestly believe as though their colleagues really come to work every day and collect a salary in order to set them up and ruin their lives any way they can! This is a fundamentally incorrect conclusion, but it has a deeply destructive effect on any team, and its members can begin to take revenge on their colleagues and actually start making their lives more difficult.

Projects are done slowly and badly

All the principles here have already been explained above. First of all, everyone is always busy. Second of all, a project usually demands the cooperation of several divisions – but how can you make that happen if people don’t want to interact? For that matter, absolutely everyone who wants to push through any changes at all runs into resistance from their colleagues who, first of all, are busy up to their eyeballs, and second of all, who are principally opposed to doing anything together. Besides, it’s often the case that instead of working on the project, all members of the working group spend their time and energy on passing the buck off to one another – a necessary precaution in the event of failure. This leads to projects being done slowly, for a lot of money, and with results that, to put it lightly, are nothing to write home about…

What are you managing, anyway?

If none of the aforementioned points sounds familiar to you, then you can stop reading here: no matter what, you won’t get anything useful out of my book, and will just be wasting your time reading it instead! However, more likely than not, these examples illustrate the state of things (in whole or part) within your company. For that matter, we must note that you know about all of these existing problems and you don’t like them, but you can’t do anything about them. If we return to the analogy of driving a car, then this means that you’ve lost control. At the core of things, you were never in control in the first place; the situation had merely yet to become critical, and you were being carried in the direction where you wanted to go anyway. Now, however, everything has changed, and that means that you need to change, too!

Generally speaking, the "teal" alternative arose specifically to solve these essential problems that accumulated under all previous systems of management and create a new one where such problems cannot exist a priori. We have to note that this has worked in practice, and many managers in many companies have already been able to start using teal tools! That means that if people have the desire, the will, the right creative approach, and the knowledge that you’re about to gain, you’ll be able to do so, too!

But first of all, we have to stop and figure out exactly what it is that you’re managing. One person might say that it’s a company. Another will say that it’s people. A third will say resources. As strange as it is, all of these answers are incorrect. The only thing that anyone actually manages is their influence on other people. Nothing else. Period.

It will probably seem to you that this isn’t much at all, compared to what was listed above. But let’s be realists here. In reality, all we can manage is our influence on the people around us. That has always been the case. Well, if that was enough to let the greatest leaders of the past accomplish those great feats for which we remember them, that means it will be enough for you, especially if you approach the management of your influence on others conscientiously.

For starts, learn to notice the specific kind of influence you have on people and what you get as a result. I have often encountered situations when a manager seems to say, "Full speed ahead!" but it’s nothing but empty words. Instead, all of their actions seem to "pull up the handbrake," so to speak, and then they are surprised that the company is stuck in place and not moving anywhere! It’s worth remembering that this influence comes from every word and behavior, from any gesture or facial expression, and even from silence, inaction or a lack of reaction.

Under no circumstances am I pushing you towards insincerity. That is a worthless endeavor since everyone around you will sense those signals that we cannot consciously manage. I’m asking you to comprehend the results of your influence on your subordinates, to take responsibility for it, and to search inside yourself for those deeper reasons that force us to behave in a certain way. Finally, I am asking you to change your interpretation of the situation. As a result, you will transform your own actions, and thanks to that, new results will follow.

Chapter Two.

What?

The spread of teal tools has already become a trend in transforming management systems, but to this day there remains much confusion about the most elementary questions – both for those who have only just encountered the basic terms and for those who have already studied them in some depth. Around some of these terms, heated arguments have even begun. To be fair, it’s worth noting that it’s primarily theorists who butt heads on such matters. Practitioners simply start realizing the necessary changes in their companies, either overall or within individual departments, insofar as they understand those changes themselves. As luck would have it, they often achieve excellent results, even though they might not have understood everything perfectly to begin with. However, forward movement straightens out these misunderstandings and results in the necessary course corrections on the whole. By the way, some people value teal management for these qualities in particular: its flexibility, speed and efficiency which, aside from all of its other qualities, allow it to easily prevail in a competitive fight with antiquated management systems.

“Teal”

Theoretical arguments begin at the most elemental level, around the name itself: the term “teal.” The thing is that in his book “Reinventing Organizations”, 3 Frederic Laloux based his color scheme on the one in Don Beck’s “Spiral Dynamics”. 4 However, he changed the colors around a little in order to make the development dynamics of a company’s organizational system from one level of his theory to the next fit into the spectrum of visible light: from infrared, which corresponds to the most primitive forms of organization for him, to ultraviolet, which he incidentally doesn’t even mention in his work. The thing is that he stops at teal, which he discovered in the course of his studies in the most contemporary forms of companies at the time. For that matter, classical spiral dynamics has a “teal” of its own, not described in “Reinventing Organizations”. Frederic Laloux’s teal corresponds to “yellow” in spiral dynamics, while “amber” (a shade of yellow) fits in with Don Beck’s deep blue. Besides this, there are other color schemes of management systems as well: in the fourth chapter, you will find a comparison table that I put together specifically to help my readers. To put it simply, before you call out a color, you have to clearly define which color scheme you’re talking about.

In reality, this doesn’t have any influence whatsoever, but such arguments only serve to confuse the situation further. In order to slice through this Gordian knot, we will note that all such discussions boil down to the definition of terms that will be used in our further discussions. That means that proof of the correctness of one version or another doesn’t exist, and cannot exist in principle. In any branch of science, there exists a moment when specialists stop arguing and start negotiating as to what they will begin to call by a particular name or other, because without such an agreement, any further debates are essentially impossible. We have to note that many arguments simply would never have happened if the arguing parties had simply started by defining those words that they planned on using over the course of the argument. That’s why I propose agreeing on the use of "teal" within the framework of this book in terms of management styles as it is understood in "Reinventing Organizations." After all, it is Frederic Laloux to whom we owe the popularization of this term. The aforementioned "Spiral Dynamics" even though it was published significantly earlier, is far less well-known, and often our fellow countrymen find out about it only after getting acquainted with "Reinventing Organizations" and in an attempt to read something further on the subject.

As far as specialized literature that describes the practices of transitioning to the teal system of management is concerned, I recommend that you get acquainted with the bibliography at the end of this book – or visit http://biryuzovie.ru/category/poleznye-knigi/. There you can find a specially assembled list of publications, along with my comments, which I’m constantly augmenting and updating.

There’s one other important aspect. I already spoke about this in the foreword, but I will emphasize it one more time: "teal" organizations and managers don’t exist in nature, and currently cannot even exist theoretically. At the moment, the only thing that can be teal is management within an organization, and I must admit that I have yet to find a single one where it completely corresponds to its definition. The image of the companies illustrated in Frederic Laloux’s book is so tempting that it would seem that real "teal" companies are lurking behind every corner! Alas, that is not the case. I know what I’m talking about, because I have personally been in contact with the founders and employees of six of the firms mentioned by the author, and have also read books written by the aforementioned managers. Their organizations are not "teal," although many teal management tools described by Laloux are used there.

That seems clear enough; these are the pioneers, after all. Who would call the very first capitalists who challenged the reign of bureaucracies "corporations," either? Was it even possible to predict the future of all-powerful bureaucracies in the very first vicars of ancient monarchs, who had previously always collected taxes and held court over all the territory he ruled in person? Any new form of leadership sharply differs from that which preceded it at first glance, but of course, it doesn’t show its full and unvarnished essence right away. Just imagine what teal management would look like in organizations when it begins to saturate all of human culture, rather than being a strange exception from the general rule as it is now – whether for owners, managers and employees or for suppliers, public institutions and clients.

That’s why the most important task today is to find the tools of teal management, employing them in practice and popularizing successful experiences around the world, rather than bragging that you’re already "teal" and your neighbor isn’t. For now, we’re all very far from perfection! To make it easier to understand, I’ll take a more familiar analogy. What would you think about a person who told you that a particular firm is automated, and another one isn’t? Personally I’d decide that they aren’t using the term at hand very correctly: after all, you can only automate a process, not a whole firm. What’s more, the automation of a process has specific goals and clear resources that can be compared with other cases. You can wrack your brains applying the logic to a firm ad infinitum, constantly applying new materials and tools to the process.

And what would you say in response to the assertion that one company is more "automated" than another? How can you even comprehend this if in the first case, all orders are automatically for suppliers while accounting for numerous factors, but in the second case, everything is done in Excel, with no guarantee that all the data from the accounting system makes it into the spreadsheet, and some things entered completely manually? On the other hand, what if in the second case, all cost accounting with suppliers is done using an electronic workflow, while in the first case, people still run around with stacks of papers and spending a month on accounting records at the beginning of every quarter? Based on this analogy, you might get the sense that an organization’s color categorization will always be mixed somehow, but on the other hand, you can try to speak about the color of specific divisions and departments inside of it. No, you can’t do that, either! In different situations, a single manager might behave in completely different ways! Yes, some methods may be more or less characteristic for them, but I am principally opposed to calling a person "red," "teal" or anything in between, even in extreme situations.

Teal leadership – such leadership as increases or at least supports the independence and integrity of an organization’s employees in order to achieve its evolutionary goals.

There are many tools of teal management, and the consistent use of the majority of them for an increasingly wide spectrum of situations is the very path that any organization or manager can use to make significant changes for the better. The most important thing is not to rest on your laurels, always trying to solve problems in new and different ways. Soon, others will start to call such a company "teal," even though this would be a terminological error. After all, there is always an opportunity to do something else in this direction, and it’s far better for a company to focus on specific actions, rather than waving its teal flag in the air.

But we still haven’t answered the question of what this mystical teal management is. According to Frederic Laloux, it is such leadership as increases or at least supports the independence and integrity of an organization’s employees in order to achieve its evolutionary goals. Let’s sort out each of the three "whales" of teal management: evolutionary goal, integrity and independence. Incidentally, it’s interesting that all of these components depend very closely on one another: you can feel this immediately as soon as you try to incorporate any of them in practice, whether at the company level or in just one of its departments.

Evolutionary goal

A company’s evolutionary goal is a result toward which a company strives, having chosen it as the main focus for all of its actions. A company’s evolutionary goal can be easily confused with its mission, which is no surprise: they often sound very similar to one another. But this is only on the surface: in fact, there is indeed a difference between them, and a very significant one at that. Let’s sort out the definitions. A mission expresses what the company does, while the evolutionary goal expresses what should happen as a result of the company’s work. If the mission is inseparable from the organization, then the evolutionary goal demands a description of a result without any ties to a specific organization. For example, a doctor’s mission is to heal people, while their evolutionary goal is for all people to be healthy. In the case of the mission, all other doctors keep one specific doctor from healing patients by performing the same process themselves. However, when taken together, the entire medical community can only help achieve the evolutionary goal. An even larger difference can be seen in the decision-making process in those cases when the mission or evolutionary goal becomes incompatible with the process of making money. An honest company will then rewrite their mission so that it applies to a new type of money earning, while a dishonest company will simply go on making money however necessary without changing its mission. A company with an evolutionary goal, on the other hand, does not do anything that does not directly contribute to its fulfillment in principle, even if it can make them money. The thing is that an organization defines its mission based on its individual needs, while a company is created in order to achieve an evolutionary goal. This means that an evolutionary goal is greater than the company’s own good, and a company will stop at nothing in order to achieve it, even if in the process, it must cardinally change or even stop functioning completely. For this exact reason, competition doesn’t exist for a company with an evolutionary goal – they can only help a company achieve that goal. They’re not competitors, but colleagues instead