полная версия

полная версияBrazilian Literature

What of the effect of this milieu and this racial blend upon the nation’s tongue and its creative output? The Brazilian is by nature melancholy, for melancholy is an attribute of each of the three streams that flow in his blood. The peculiar, haunting sadness of the Portuguese lyric muse is summed up in their untranslatable word “saudade”;11 both the conquered native and the subjected black are sad, the first through the bepuzzled contact with superior natural forces, the second through the wretchedness of his economic position. It has been recognized that the climate of Brazil has resulted in a lyrism sweeter, softer and more passionate than that of the Portuguese. “Our language,” says Romero, “is more musical and eloquent, our imagination more opulent.” So, too, De Carvalho: “Brazilian prosody has more delicate accents than the Portuguese and numerous interesting peculiarities.”

In the matter of linguistic modification, as of racial blend and national psychology, we of the North have problems similar to those of the Brazilians, – problems often enough obscured by unscientific, sentimental fixations or political dogma. The simple fact is that life, in language as in biology, is change. Whether we are concerned with the evolution of English in the United States, of Spanish in the cluster of Spanish-American republics, or of Portuguese in Brazil, change is the inevitable law. For the Spanish of Spanish-America, Remy de Gourmont, with his insatiable appetite for novelty, originated the term neo-Spanish. It met with much opposition from the purists, yet it recognizes the ineluctable course of speech. The noted Colombian philologist Rufino Cuervo, in a controversy with the genial conservative Valera, voiced his belief that the Spanish of the new world would grow more and more unlike the parent tongue.12 In the same spirit, if with most unacademic hilariousness, Mencken has, in The American Language,13 indicated the lines of cleavage between English and “American.” Brazilian scholars have naturally assumed a similar attitude toward their own language and have, likewise, met with the opposition of the purists. It does not matter, for the purpose of the present discussion, whether the linguistic cleavage in any of the instances here given will eventually prove so definite as to originate new tongues. Such an outcome is far less probable today than it was, say, in the epoch when Latin, through its vulgar form, was breaking up into the Romance languages. Widespread education and the printing press are conserving influences, acting as a check upon capricious modification.

One of the soundest and most sensible documents upon the Portuguese language in Brazil comes from the pen of the admirable critic José Verissimo.14 “As a matter of fact,” he writes, “save perhaps in the really Portuguese period of our literature, which merely reproduced in an inferior fashion the ideas, the composition, the style and the language of the Portuguese (already entered upon its decadence), authors never wrote in Brazil as in Portugal; the masters of language abroad never had disciples here to rival them or even emulate them… It would be a pure absurdity, then, to expect the Brazilian, the North American or the Spanish-American to write the classic tongue of his mother country.”

Chaucer wrote “It am I” where we would say “It is I” and where current colloquial usage, perhaps foreshadowing the accepted standard of tomorrow, says “It’s me.” English changes in England; why shall it cease to change in the United States? And justly, Verissimo asks a similar question for Brazil. “I have always felt,” he remarks somewhat farther on, “that the Portuguese tongue never attained the discipline and the relative grammatical and lexical fixity that other languages arrived at. I do not believe that among cultured tongues there is one that has given rise to so many controversial cases, or to so many and so diverse contradictions among its leading writers.” The fight about the collocation of personal pronouns is waged so earnestly in Brazil that it has become as funny, in some of its aspects, as the quarrel of the “lo-istas” and the “le-istas” in Spain. And so true are Verissimo’s words that as late as March, 1921, a writer could complain in the Revista do Brazil15 that “we are at the very height of linguistic bolshevism”; the very next month, indeed, the editorial board of the same representative intellectual organ found it necessary to comment upon the various systems of orthography employed by its contributors and to designate a choice.16 Verissimo, in accordance with A. H. Sayce, takes as his standard of grammatical correctness that which is “accepted by the great body of those who speak a language, not what is laid down by a grammarian.” Still more to the point, Verissimo, who was a man of exemplary honesty and fearlessness in a milieu that easily tempts to flattery and the other social amenities, declares that “if we are by language Portuguese, if through that tongue our literature is but a branch of the Portuguese, we have already almost ceased to be such … because of our fund of ideas and notions, which were all constituted outside of Portuguese influence.” The important thing, then, is “to have something to say, an idea to express, a thought to transmit. Without this, however deep his grammatical knowledge of the language, however perfectly he apes the classics, no man is a writer.” Platitudinous, perhaps, but how often some platitudes bear repetition!

The language of Brazil, then, is not the Portuguese of Lisbon. From the phonological viewpoint there is less palatalization of the final s and z than is customary in Portugal; Brazil has a real diphthong ou, which in Lisbonese has become a close o or the diphthong oi. Its pronunciation of the diphthong ei is true, whereas in Lisbon this approximates to ai (with a as in English above, or like the u of cut). Neither is the grammar identical with that of Portugal. “The truth is, that by correcting ourselves we run the danger of mutilating ideas and sentiments that are not merely personal. It is no longer the language that we are purifying; it is our spirit that we are subjecting to inexplicable servility. To speak differently is not to speak incorrectly… To change a word or an inflexion of ours for a different one of Coimbra17 is to alter the value of both in favor of artificial and deceptive uniformity.”18

Brazilianisms, so-called, make their appearance very early; they are already present in the letters sent by the Jesuits, as well as in the old chronicles. New plants, new fruits, new animals compelled new words. Native terms enriched the vocabulary. Of course, as has happened with us, often a word for which the new nation is reproached turns out to be an original importation from the motherland. One of the oldest documents in the history of Brazilianisms appeared in Paris during the first quarter of the XIXth century and is reprinted by João Ribeiro as a rarity little known to his countrymen; it formed part of the Introduction à l’Atlas ethnographique du globe, prepared by Adrien Balbi and covering the races and languages of the world. The Portuguese section was entrusted to Domingos Borges de Barros, baron and later viscount de Pedra Branca, a warm advocate of Brazilian independence, then recently achieved. This, according to Ribeiro, is supposed to constitute the “first theoretical contribution” to the study of Brazilianisms. It is written in French, and because of its documentary importance I translate it in good measure:

“Languages reveal the manners and the character of peoples. That of the Portuguese has the savor of their religious, martial traits; thus the words honnête, galant, éate, bizarre, etc., possess a meaning quite different from that they have in French. The Portuguese tongue abounds in terms and phrases for the expression of impulsive movements and strong actions. In Portuguese one strikes with everything; and when the Frenchman, for example, feels the need of adding the word coup to the thing with which he does the striking, the Portuguese expresses it with the word of the instrument alone. One says, in French, un coup de pierre; in Portuguese, pedrada (a blow with a stone); un coup de couteau is expressed in Portuguese by facada (a knife thrust) and so on…

“Without becoming unidiomatic, one may boldly form superlatives and diminutives of every adjective; this is done sometimes even with nouns. Harshness of the pronunciation has accompanied the arrogance of expression… But this tongue, transported to Brazil, breathes the gentleness of the climate and of the character of its inhabitants; it has gained in usage and in the expression of tender sentiments, and while it has preserved all its energy it possesses more amenity…

“To this first difference, which embraces the generality of the Brazilian idiom, one must add that of words which have altogether changed in accepted meaning, as well as several other expressions which do not exist in the Portuguese language and which have been either borrowed from the natives or imported into Brazil by the inhabitants of the various oversea colonies of Portugal.”

There follow some eight words that have changed meaning, such, for example, as faceira, signifying lower jaw in Portugal, but coquette in Brazil; as a matter of fact, Ribeiro shows that the Portuguese critics who censured this “Brazilianism” did not know the history of their own tongue. In the XVIIth century faceira was synonymous with pelintra, petimêtre, elegante (respectively, poor fellow, dandy, fashionable youth); it became obsolete in Portugal, but in Brazil was preserved with exclusive application to the feminine. The Brazilian words unknown in Portugal are some fifty in number upon the Baron’s list.

Costa finds that Portuguese, crossing the Atlantic, “almost doubled its vocabulary, accepting and assimilating a mass of words from the Indian and the Negro. Through the influence of the climate, through the new ethnic elements, – the voluptuous, indolent Negro and Indian, passionate to the point of crime and sacrifice, – the pronunciation of Portuguese by the Brazilian acquired, so to say, a musical modulation, slow, chanting, soft, – a language impregnated with poesy and languor, quite different from that spoken in Portugal.”19

IVA new milieu and a racial amalgamation that effect changes in speech are bound soon or late to produce a new orientation in literature. The question whether that literature is largely derivative or independent is relatively unimportant and academic, as is the analogous question concerning the essential difference of language. The important consideration for us is that the law of change is operating, and that the change is in the direction of independence. Much has been written upon the subject of nationalism in art – too much, indeed, – and of this, altogether too large a part has been needlessly obscured by the fatuities of the narrowly nationalistic mind. There is, of course, such a thing as national character, though even this has been overdone by writers until the traits thus considered have been so stencilled upon popular thought that they resemble rather caricatures than characteristics. True nationalism in literature is largely a product of the writer’s unconscious mind; it is a spontaneous manifestation, and no intensity of set purpose can create it unless the psychological substratum is there. For the rest, literature belongs to art rather than to nationality, to esthetics rather than to politics and geography.20 The consideration of literature by nations, then, is itself the province of the historian of ideas; it is, however, a useful method of co-ordinating our knowledge and of explaining the personality of a country. If I bring up the matter here at all it is because such a writer as Sylvio Romero, intent upon emphasizing national themes, now and again distorts the image of his subject, mistaking civic virtue and patriotic aspiration for esthetic values, or worse still, deliberately exalting the former over the latter. The same Romero, for example, – a volcanic personality who never erred upon the side of modesty, false or true, – speaks thus of his own poetry: “… I initiated the reaction against Romanticism in 1870…” And how did he initiate it? By calling for a poetry in agreement with contemporary philosophy. Now, it is no more the business of poetry to agree with contemporary philosophy than for it to “agree” with contemporary nationalism. Goethe, reproached for not having taken up arms in the German War of Liberation, “or at least co-operating as a poet,” replied that it would have all been well enough to have written martial verse within sound of the enemy’s horses; however, “that was not my life and not my business, but that of Theodor Körner. His war-songs suit him perfectly. But to me, who am not of a warlike nature and who have no warlike sense, war-songs would have been a mask which would have fitted my face very badly… I have never affected anything in my poetry… I have never uttered anything which I have not experienced, and which has not urged me to production. I have only composed love-songs when I have loved. How could I write songs of hatred without hating!” Those are the words of an artist; they could not be understood by the honourable gentleman who not so long ago complained in the British parliament because the poet laureate, Mr. Robert Bridges, had not produced any appropriate war-verse in celebration of the four years’ madness.

If, then, we note the gradual resurgence of the national spirit in Brazilian letters, it is primarily as a contribution to a study of the nation’s self-consciousness. The fact belongs to literary history; only when vitalized by the breath of a commanding personality does it enter the realm of art. The history of our own United States literature raises similar problems, which have compelled the editors of The Cambridge History of American Literature to make certain reservations. “To write the intellectual history of America from the modern esthetic standpoint is to miss precisely what makes it significant among modern literatures, namely, that for two centuries the main energy of Americans went into exploration, settlement, labour for sustenance, religion and statecraft. For nearly two hundred years a people with the same traditions and with the same intellectual capacities as their contemporaries across the sea found themselves obliged to dispense with art for art.”21 The words may stand almost unaltered for Brazil. It is indicative, however, that where this condition favoured prose as against verse in the United States, verse in Brazil flourished from the start and bulks altogether too large in the national output. We may take it, then, as axiomatic that Brazilian literature is not exclusively national; no literature is, and any attempt to keep it rigidly true to a norm chosen through a mistaken identification of art with geography and politics is merely a retarding influence. Like all derivative literatures, Brazilian literature displays outside influences more strongly than do the older literatures with a tradition of continuity behind them. The history of all letters is largely that of intellectual cross-fertilization.

From its early days down to the end of the XVIIIth century, the literature of Brazil is dominated by Portugal; the land, intellectually as well as economically, is a colony. The stirrings of the century reach Brazil around 1750, and the interval from then to 1830, the date of the Romanticist triumph in France, marks what has been termed a transitional epoch. After 1830, letters in Brazil display a decidedly autonomous tendency (long forecast, for that matter, in the previous phases), and exhibit that diversity which has characterized French literature since the Romantics went out of power. For it is France that forms the chief influence over latter-day Brazilian letters. So true is this that Costa, with personal exaggeration, can write: “I consider our present literature, although written in Portuguese, as a transatlantic branch of the marvellous, intoxicating French literature.”22 There can be no doubt as to the immense influence exercised upon the letters of Spanish and Portuguese America by France. A Spanish cleric,23 author of an imposing fourteen-volume history of Spanish literature on both shores of the Atlantic, has even made out France as the arch villainess, who with her wiles has always managed to corrupt the normally healthy realism of the Spanish soul. Only yesterday, in Brazil, a similar, if less ingenious, attack was launched against the same country on the score of its denationalizing effect. Yet it is France which was chiefly responsible for that modernism (1888-) which infused new life into the language and art of Spanish America, later (1898) affecting the motherland itself. And if literary currents have since, in Spanish America, veered to a new-world attitude, so are they turning in Brazil. From this to the realization that Art has no nationality is a forward step; some day it will be taken. As in the United States, so in Brazil, side by side with the purists and the traditionalists a new school is springing up, – native yet not necessarily national in a narrow sense; a genuine national personality is being forged, whence will come the literature of the future.

As to the position of the writer in Brazil and Spanish America, it is still a very precarious one, not alone from the economic viewpoint but from the climatological. “Intellectual labour in Brazil,” wrote Romero, “is torture. Wherefore we produce little; we quickly weary, age and soon die… The nation needs a dietetic regimen … more than a sound political one. The Brazilian is an ill-balanced being, impaired at the very root of existence; made rather to complain than to invent, contemplative rather than thoughtful; more lyrical and fond of dreams and resounding rhetoric than of scientific, demonstrable facts.” Such a short-lived, handicapped populace has everything to do with literature, says this historian. “It explains the precocity of our talents, their speedy exhaustion, our facility in learning and the superficiality of our inventive faculties.”

Should the writer conquer these difficulties, others await him. The reading public, especially in earlier days, was always small. “They say that Brazil has a population of about 13,000,000,” comments a character in one of Coelho Netto’s numerous novels. “Of that number 12,800,000 can’t read. Of the remaining 200,000, 150,000 read only newspapers, 50,000 read French books, 30,000 read translations. Fifteen thousand others read the catechism and pious books, 2,000 study Auguste Comte, and 1,000 purchase Brazilian works.” And the foreigners? To which the speaker replies, “They don’t read us. This is a lost country.” Allowing for original overstatement, the figures do not, of course, hold for today, when the population is more than twice the number in the quotation, when Netto himself goes into edition after edition and, together with a few of his favoured confrères, has been translated into French and English and other languages. But they illustrate a fundamental truth. Literature in Brazil has been, literally, a triumph of mind over matter. Taken as a whole it is thus, at this stage, not so much an esthetic as an autonomic affirmation. Just as the nation, ethnologically, represents the fusion of three races, with the whites at the head, so, intellectually, does it represent a fusion of Portuguese tradition, native spontaneity and modern European culture, with France still predominant.

We may recapitulate the preceding chapter in the following paragraph:

Brazilian literature derives chiefly from the Portuguese race, language and tradition as modified by the blending of the colonizers with the native Indians and the imported African slaves. At first an imitative prolongation of the Portuguese heritage, it gradually acquires an autonomous character, entering later into the universal currents of literature as represented by European and particularly French culture. French ascendency is definitely established in 1830, and even well into the twentieth century most English, German, Russian and Scandinavian works come in through the medium of French criticism and assimilation.24

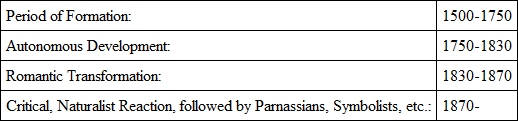

VNo two literary historians of Brazil agree upon a plan of presentation. Fernandez Pinheiro (1872) and De Carvalho (1919) reduce the phases to a minimum of three; the first, somewhat too neatly, divides them into that of the Formative Period (XVIth through XVIIth century), the Period of Development (XVIIIth century), the Period of Reform (XIXth century); the talented De Carvalho accepts Romero’s first period, from 1500 to 1750, calling it that of Portuguese dominance, inserts a Transition period from 1750 to the date of the triumph of French Romanticism in 1830, and labels the subsequent phase the Autonomous epoch. This is better than Wolf’s five divisions (1863) and the no less than sixteen suggested by the restless Romero in the résumé that he wrote in 1900 for the Livro do Centenario. I am inclined, on the whole, to favour the division suggested by Romero in his Historia da Literatura Brasileira (1902).25

The fourth division allows for the decidedly eclectic tendencies subsequent upon the decline of Romanticism.

Accordingly, the four chapters that follow will deal succinctly with these successive phrases of the nation’s literature. Not so much separate works or men as the suffusing spirit will engage our attention; what we are here interested in is the formation and development of the Brazilian imaginative creative personality and its salient products.26

CHAPTER II

PERIOD OF FORMATION (1500-1750)

The Popular Muse – Sixteenth Century Beginnings – Jesuit Influence – Seventeenth Century Nativism – The “Bahian” school – Gregorio de Mattos Guerra – First Half of Eighteenth Century – The Academies – Rocha Pitta – Antonio José da Silva.

IIt is a question whether the people as a mass have really created the poetry and legends which long have been grouped under the designation of folk lore. Here, as in the more rarefied atmosphere of art, it is the gifted individual who originates or formulates the central theme, which is then passed about like a small coin that changes hands frequently; the sharp edges are blunted, the mint-mark is erased, but the coin remains essentially as at first. So that one may agree only halfway with Senhor De Carvalho,27 when he writes that “true poetry is born in the mouths of the people as the plant from wild and virgin soil. The people is the great creator, sincere and spontaneous, of national epics, the inspirer of artists, stimulator of warriors, director of the fatherland’s destinies.” The people furnishes rather the background against which the epics are enacted, the audience rather than the performers. Upon the lore and verses of their choosing they stamp the distinguishing folk impress; the creative inspiration here, as elsewhere, is the labour of the salient individual.

The study of the Brazilian popular muse owes much to the investigations of the tireless, ubiquitous Sylvio Romero, whom later writers have largely drawn upon.28 There are no documents for the contributions of the Africans and few for the Tupys, whom Romero did not credit with possessing a real poetry, as they had not reached the necessary grade of culture. The most copious data are furnished, quite naturally, by the Portuguese. Hybrid verses appear as an aural and visible symbol of the race-mixture that began almost immediately; there are thus stanzas composed of blended verses of Portuguese and Tupy, of Portuguese and African. Here, as example, is a Portuguese-African song transcribed by Romero in Pernambuco:

Você gosta de mim,Eu gosto de você;Se papa consentir,Oh, meu bem,Eu caso com você…Alê, alê, calunga,Mussunga, mussunga-ê.Se me dá de vestir,Se me dá de comer,Se me paga a casa,Ob, meu bem,Eu moro com você…Alê, alê, calunga,Mussunga, mussunga-ê. 29On the whole, that same melancholy which is the hallmark of so much Brazilian writing, is discernible in the popular refrain. The themes are the universal ones of love and fate, with now and then a flash of humour and earthy practicality.