полная версия

полная версияThe Present State of Hayti (Saint Domingo) with Remarks on its Agriculture, Commerce, Laws, Religion, Finances, and Population

The smaller lake, called Etang du Cul de Sac, contains fresh water, and the fish in it are very numerous. The soil in the vicinity of these lakes is the deepest and richest mould, and not having for years been disturbed for tillage, has become highly nutritive, from the animal and vegetable matter which decays annually upon its surface.

The value of land throughout the republic is greatly deteriorated, from the impossibility of making a money value from it within any moderate time. Labour being so high, and the difficulty of finding labourers for cultivation so very great, that the lands in the possession of the government lie in an untilled state, without any person evincing the slightest disposition to purchase them. Land also in the possession of individuals is similarly circumstanced; and those who are large proprietors cannot effect a sale of any produce which they may have beyond the quantity which they can consume; consequently a proprietor may have an immense extent of land, and yet be quite unable to derive any benefit from it by cultivation, or to convert it into money, for the want of purchasers. Thus, as I have before stated, there is no individual wealth in the country, because, although a man may have very large landed possessions, still those possessions are unavailable, for they produce him nothing, as he can seldom find persons disposed either to occupy or purchase them. There are some instances of proprietors leasing their lands to persons who undertake to cultivate them, for which they receive about one-third of the produce; but this is far from being general, and I imagine can only be accomplished by military men who have the command of troops, and who are thereby enabled to till them by working parties daily sent out for that purpose.

The finest land in the republic would not sell for more than sixty dollars per acre, although contiguous to a port for shipping, and of a quality so strong and nutritive, as to be capable of growing any of the tropical productions. The mountain-lands, and the lighter descriptions in the plains, suitable for cocoa and cotton, can be obtained for a price varying between twenty and thirty dollars in any quantity from ten to five hundred acres. In the plains of the Artibanite, where the soil is exceedingly rich and fertilized by the overflowings of that river in the months of May and November, and which has been yearly improving its condition, from having been upwards of thirty years out of cultivation, I have known small plots of land, for horticultural purposes, sold for forty dollars per acre. In those districts where indigo and cotton were formerly most generally planted, for the growth of which the soil is suitable, the situation peculiarly adapted, and the climate and seasons congenial, the price of land seldom exceeds thirty dollars per acre. I know an instance of a sale of land, once an old cotton plantation, which only brought twenty dollars per acre for one part, and about twelve for another.

In the northern department, about Limonde and La Grande Rivière, land is exceedingly low, and notwithstanding its high repute for all the purposes of cultivation, it seldom exceeds forty or forty-five dollars per acre, and even at those prices it is difficult to find purchasers, except for mere plots to be occupied in raising vegetables. The finest pasture-lands, having all the advantages of shade and water, and in all the luxuriance of vegetation, can scarcely find purchasers, and will not bring above forty dollars per acre. With respect to lands on the coast they are generally in waste, unless they happen to be immediately in the vicinity of a town, when some of them are occupied as small settlements for vegetables and for raising poultry for the markets: but there are no extensive plantations of sugar or coffee situate very near the sea, although formerly the whole coast was in cultivation as far as it was practicable to extend it.

In the plains of Cul de Sac, in the neighbourhood of La Croix des Bouquets, the land is a little occupied, but in possession of individuals who have held it since the distribution in the time of Toussaint and Dessalines; and although in this part of the country the soil is exceedingly deep and strong, land hardly finds purchasers. Land again in the mountains varies in price according to its situation. In those valleys surrounded by the cordilleras that are so numerous in the country, and in which the verdure is constant, which are finely watered, and have a delightful temperature through the year, the land sometimes brings fifty dollars per acre, whilst tracts exposed to the north and north-easterly winds, and having rapid descents, are seldom worth purchasing, and few people buy them; they are generally given by the government to superannuated soldiers, who are allowed to leave the army and turn cultivators. Land in the towns and cities is sold at moderate prices, much lower than might be imagined. A lot, containing a frontage of sixty feet, with a depth of forty or fifty feet, eligibly situate for the purposes of trade, may be bought in Port au Prince for about two hundred dollars. This may seem surprising to persons unacquainted with the country, and who have been led to believe that Hayti is in a most flourishing state; but it is true, and at once shews that poverty is generally prevalent, and that there is no security for property in whatever commodity it may be vested. Houses and land are a very insecure tenure under such a government as that which at present exists in Hayti, and whilst such a constitution endures, and such inefficient persons are permitted to command, but little improvement can be expected, and the value of property, instead of increasing, will certainly decline.

CHAPTER XI

Agriculture. – Crops in Toussaint’s and Dessalines’ time. – System of Christophe and Petion. – Decline under Boyer. – Crops in his time. – Attempts to revive it. – Coercion resorted to. – Code Rural. – doubts on enforcing its clauses. – Disposal of lands. – Consequences from it. – Incompetency of planters. – State of cultivation of sugar, coffee, cocoa, cotton, indigo. – Free labour. – Consequences arising from it. – its inefficacy, etc.

I shall now endeavour to detail the decline of agriculture in Hayti, and to offer a few remarks upon its present state; as well as to shew that under the present inefficient government, very faint hopes only can be held out of any revival, or that the republic of Hayti can ever reach that eminence and repute which once belonged to Saint Domingo as a French colony.

In various parts of this work I have observed that the decline of agriculture commenced immediately after the improvident and impolitic measures pursued by the national assembly of France, and after the first partial revolt of the slave population: and that all the energy of the successive chiefs who have subsequently governed the country, and who have promulgated several edicts to enforce or encourage cultivation, has not been sufficiently powerful to keep up that regular system of tillage from which, in her former state, she derived such advantages. True it is, that great efforts were made by Toussaint, Dessalines, and Christophe, to infuse into the people a taste for husbandry, and to impress on them that the surest way to arrive at affluence is by an undeviating perseverance in the cultivation of those lands which had fallen into their possession; that the only true riches of a country are to be derived from the soil; and that commerce, although a very powerful auxiliary, is only a secondary means by which a nation can arrive at opulence, or its people attain to any advancement in wealth. But their efforts were unavailing in part, though they certainly did more to keep up cultivation than has been attempted since their days. The proclamation of Toussaint in the year 1800 was a powerful document, and had a great effect as an incitement to labour; and his solicitude respecting an intercourse with Europe and the United States shewed that he wished to adopt every expedient by which encouragement could be given to the cultivator; to find a vent for their productions, in order to enhance their value, and thus stimulate the occupiers of the soil to further exertions. He was extremely solicitous to introduce an organized system of cultivation which would eventually aggrandize his country. Coercion he knew to be absolutely necessary. He was well aware that without this nothing could be accomplished. But the state of popular feeling rendered the rigid exaction of duty in agricultural labour a dangerous experiment; he therefore decided on adopting a mean between two extremes which, while it excited no dissatisfaction among the people, would provide for the exigences of his government.

Toussaint unquestionably pursued a plan which, had he not been seized by the French general, and in defiance of the laws of honour and nations so inhumanly transported to France, would in time have so far restored agriculture, and placed his country in so flourishing a condition, that in a few years it would have rivalled even the most happy period of its agricultural and commercial greatness. His object was clearly to advance by degrees, and to stimulate his people to the culture of the soil, by holding it up as the most noble pursuit of which they could possibly make choice; to infuse into them a taste for industry; and to give them a relish for those rural occupations which cultivation required, and for which, the extremely rich and fertile soil of the country would so amply and so quickly reward them. He had also made great strides towards impressing them with an idea that they had many wants, which, although artificial, yet were necessary towards advancing them in the opinion of the world. To teach them this effectually, and to impress it seriously, would have been a work of time, but he made great efforts, and he began to perceive that they had not been unavailing. But wherever he discovered an invincible indisposition to receive these salutary lessons and a total disregard of his admonitions and persuasions, he tried what force would accomplish; and consequently the law for enforcing agriculture was enacted, and all people were directed to make choice of the plantations on which they were disposed to labour, prohibiting all persons from living in idleness and sloth. The estate and the employer being thus once selected, the labourer was not permitted to recall his choice, unless permission to do this were granted him by the officer commanding the district or one of the municipal authorities. Hence the labourers became once more slaves in fact, although not so in name.

When this law was promulgated, Toussaint began to exert the power which he possessed to enforce it, and cultivation began to raise its head in a most eminent degree. The sugar estates exhibited labour going on with the same spirit and success as in former times; the coffee settlements displayed a busy scene in every direction throughout the colony; and the cotton and cocoa plantations shewed that they were not to be neglected in the midst of this animated and interesting struggle for the revival of a country’s greatness and a nation’s wealth. But here coercion did the work, here was compulsory labour resorted to, because it was sanctioned by the law, and those who held the power were more than equal to those who felt a disposition to resist it. The whip, that symbol of office of the principal negro, was dispensed with, it is true, but the cultivators were placed under the apprehension of a more effective weapon, for they were attended through the day by a military guard, and the bayonet and the sabre superseded the cat and the lash. To the astonishment of the leading people in the country, the cultivators submitted to this coercion without a murmur; and it was not until French intrigue was industriously set to work to instil into their minds that their condition was worse than when they were slaves, that any disposition was shewn to oppose the principle of compulsory labour; and even this opposition was far from being general. When we take into consideration that the population under Toussaint had greatly diminished, and that the cultivators in his time exceeded very little more than half of the slaves that were employed in agriculture in the time of the French, and compare the returns of produce at the respective periods, it must be evident that the system of coercion resorted to by Toussaint, must have been to the full as rigid as that which existed at any former period, or it would have been impossible for him to have carried on cultivation to so great an extent.

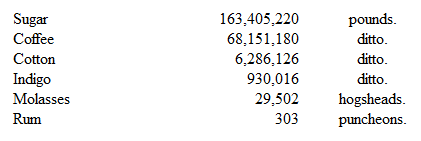

In the early part of this work I have stated the quantity of produce exported in the year 1791, which was the most flourishing period of the French, and the number of slaves that were employed in the colony. That the reader may more clearly see the difference at the two periods, I shall enumerate the principal articles again. It appears by various authorities that the exports were as follow: in 1791 —

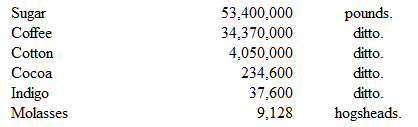

And that there were employed for all the purposes of cultivation, four hundred and fifty-five thousand slaves. The most productive year under his sway, will be found to exhibit the following returns of exports: —

According to Mr. Humboldt, the cultivators employed to carry on the whole of the works of agriculture, and to produce the above exports, did not exceed two hundred and ninety thousand. In addition to the foregoing returns should be taken into consideration the condition into which the soil had been brought by the exertions and the judicious measures pursued by this chief from the year 1798, when he became the leader of the people, to the time of his seizure. All those estates on which culture had so successfully recommenced, were so much improved by his system, that the greatest expectations were entertained respecting the produce of future exertions; but the fall of this chief, and the renewal of the contest between the people and the French, threw every thing again into confusion, and the work of cultivation for a time ceased, with the exception of the exertions made by the women, who applied themselves to labour, and their efforts were not altogether unavailing, for they proceeded with the lighter labour of the plantations, which was exceedingly beneficial.

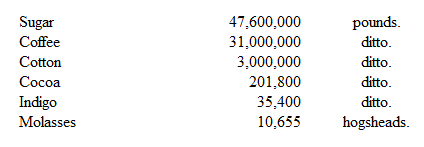

When Dessalines assumed the command, the country was in a state of great irritability, and he could not therefore devote that attention to agriculture which his predecessor had done. But when he had succeeded in expelling the French from the island, and had restored some degree of tranquillity, and the people became somewhat free from apprehension of future broils, he began to devise means for reviving cultivation; but he wanted the discretion and the temper, as well as that knowledge of the people which Toussaint possessed. The latter pursued a system of culture, that in the first instance was easy and acceptable to them, and when he saw that they began to relax in their duty, he began to enforce it more rigidly, and under the sanction of the law inflicted punishment with no light hand, in cases of disobedience and refractory conduct. But Dessalines acted differently and most injudiciously, for he rushed upon the cultivators so suddenly, and with so tyrannical a hand, that disobedience began to be general; and those people who had in his predecessor’s time been the most industrious and most forward in setting an example to their fellow-labourers became supine and inactive through his oppressive proceedings. Dessalines knew well that force alone could compel his countrymen to work, and that nothing could be obtained from them if they were left to their own will; but he was too precipitate and hasty in introducing his measures of coercion. He even compelled his soldiers to labour in the field in parties, on such of the government estates as had not been farmed out, and for which they received a trifling addition to their regular military pay. But all his exertions were ineffectual in producing such returns as those which followed the efforts of Toussaint. Both knew that coercion was the only way by which cultivation could be carried on, and they both resorted to it. With one it succeeded in a degree which equalled his most sanguine expectations, because he advanced progressively, and the people did not feel it so severely; whilst the other burst upon the cultivators with an unmerciful hand and inflicted such punishments for disobedience as made them determine on resistance, and the consequence was, that a revolt followed, and Dessalines fell. By a document given me by an individual now living in Hayti, and who was attached to the suite of the tyrant, it appears that with all his power and exertions, his returns from the soil fell much below those of his predecessor. In 1804, which seems to have yielded about the largest return of his three years, the exports were the following: —

The number of the cultivators at this period has not been stated, though I have been informed by respectable individuals that they were as numerous as in the time of Toussaint, but that from the very harsh proceedings of Dessalines a great number left their homes and fled to the eastern part of the island, and there lived in the woods and recesses of the mountains until they heard of his death.

In the time of Christophe and Petion the culture of the soil was carried on by the former with some spirit, whilst the latter allowed it to relax in a most extraordinary degree. Christophe pursued it with strong compulsory measures, as may be seen by his adoption of the code of Toussaint, but Petion left every thing to the will and inclination of his people. The government of the north, by means of its agricultural pre-eminence, had a flowing treasury, and its people advanced in affluence from the effects of industry; but the government of the south, from supineness and from a disregard of cultivation, was reduced to the lowest state of poverty, and was driven to expedients exceedingly ruinous in their consequences. By Christophe the people were taught to love agricultural pursuits, as conducive to their happiness and comforts; and were made to understand that cultivation would be enforced, and that the disobedient and the indolent would be visited with the full penalty of the law. By Petion every class of persons were permitted to pursue those courses to which their tastes and their will led them. Uncontrolled by any regulations of the state, they never pursued cultivation beyond their own immediate wants; and beyond the supply of those wants, which were inconsiderable, no surplus was left for the use of government or for the purposes of commerce. Whilst the north excited some degree of interest in the mind of the traveller as he pursued his journey through its several districts, by an appearance of industry and cultivation, the south displayed little more than occasional spots of vegetation, and the eye wandered over an expanse of country in a state of waste and neglect. The mistaken policy of Petion ruined the progress of agriculture in his part, and all his after efforts to restore its wonted vigour were ineffectual and unavailing. Fondly confiding that his people would without compulsion devote the whole of their time to the pursuits of industry, he permitted them to indulge in those propensities to which they were naturally prone. But instead of keeping pace with their northern neighbours in the progress of agricultural industry, they evidently receded beyond the possibility of recovery, and not a chance was left that agriculture would revive under the weak and ineffectual measures of Petion’s government.

Christophe most advantageously farmed out the government estates, and at the same time he gave to the farmers of them every possible support; but he most strictly bound them to push the culture of their lands as far as it was practicable from the paucity of labourers; and he also ordained the portion of labour which might be exacted from each of them. Every individual in the least acquainted with the portion of labour allotted for the slave in the British colonies will readily admit, that the labour performed by them, far from being excessive, does not exceed the ordinary labour of man in general throughout the agricultural countries in Europe or the United States of America. From every account which I have been able to collect, and from the testimony of living persons, Christophe exacted from every labourer the full performance of a day’s labour as provided for by the twenty-second article of the law for regulating the culture of soil, and which forms a part of the Code Henry, and every proprietor who did not enforce it incurred his severest censure. The only thing which impeded the great advancement of cultivation in his dominions was his contest with Petion, and the necessity which that occasioned for his keeping up a powerful military establishment, which took away the most able of the cultivators for the army.

After the union of the three divisions of the island under the republic, some hopes were entertained that Boyer would concert measures for reviving agriculture, although from his election to the presidential chair after the death of Petion, he had given no proofs, nor evinced the least desire to disturb the cultivators, but allowed them to follow such courses as seemed most congenial to their habits, and consequently, instead of any improvement in the condition of the country, there was evidently a greater decline; and as the population had been greatly increased, the whole country tranquil, and without the appearance of any interruption being given to it, a period more favourable could not have arrived for effecting a change of a system, which he must have seen was attended with the most baneful consequences.

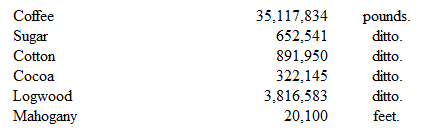

I shall now advert to the quantity of produce obtained from the soil after the union, and it seems, from the returns which were laid before the public in 1823, and subsequently from a note which I had presented to me in Hayti, that the year 1822, the first year after the union, was the most productive, and that since that period there has been an evident decline. In 1822, the exports stood thus: —

The whole value of which, in Hayti, seems to have been estimated at about nine millions, thirty thousand, three hundred and ninety-seven dollars, and the export duties one million, three hundred and sixty-five thousand, four hundred and two dollars; together, ten millions, three hundred and ninety-five thousand, seven hundred and ninety-nine dollars, or about two millions, seventy-nine thousand, one hundred and fifty-nine pounds sterling, taking the value of the dollar as in Hayti at four shillings sterling. No subsequent year has been equal in produce to 1822, and in 1825 the returns are infinitely less, for the quantity of coffee does not exceed thirty million pounds, sugar seven hundred and fifty thousand pounds, and the other articles somewhat less in proportion. The valuation of the whole in 1825 is stated at eight millions of dollars, or thereabouts. Such is the wretched state to which the improvident measures of Boyer has brought agriculture in Hayti, and in this condition would the republic have remained, had he not attended to the suggestions of men wiser than himself, who have some knowledge of governing, and who are not such bigots as to be led by a mistaken philanthropy, when they perceive their country sinking under its injurious effects.

An individual now high in the councils of Boyer made the strongest remonstrances against the unwise policy which he followed; and the late Baron Dupuy, a man who knew how the best interests of his country might be upheld, declared to him that by pursuing such a line in future he would bring the republic to the brink of ruin. That it was folly to think of any expedients for raising their national wealth and consequence, except by encouraging and enforcing the cultivation of the soil, and extending their commercial intercourse by every possible means, for that agriculture and commerce were the only sources of national wealth.