полная версия

полная версияSir Christopher: A Romance of a Maryland Manor in 1644

It would not perhaps have encouraged the lad to know that instead of thinking of him with indifference, she simply was not thinking of him at all, her entire attention being fixed upon the scene around her and the actors in it. Such beautiful girls, in their jewels and laces and brocades and high-heeled slippers! Such magnificent men, with rainbow colors in sashes and velvet coats, with ruffles of costly embroideries and buckles reflecting the light of the candles! Most gorgeous of all, Sir William Berkeley!

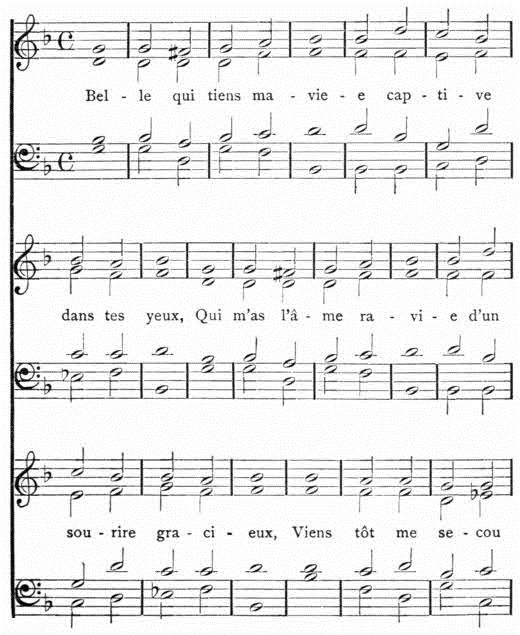

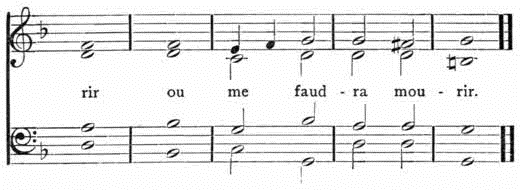

It quite took Peggy's breath away when this elegant courtier bowed before her and begged her hand for the pavan. Yet there he was, sweeping the floor before her with the white plumes of his hat and craving the honor of the dance. Whatever might be thought of Sir William's powers of governing, there could be no doubt that he understood the art of dancing, and, final test of skill, of making his partner dance well. Holding the tips of Peggy's fingers lightly, but firmly, he led her to the head of the hall, where the host and hostess stood. These they saluted gravely, she with a deep courtesy, he with an equally deep bow, his hat clasped to his heart. Then sweeping down the room they paused again before the portrait of the King, and Berkeley saluted with his sword; then on again, the hautboys keeping time while the company marked the rhythm by singing together, after the fashion introduced by Queen Henrietta's French courtiers —

At the end of the measure, the advance being ended, the retreat began, the Governor walking behind and leading his partner backward, always with delicately held finger-tips, the raised arm and rounded wrist showing every graceful curve as the girl walked.

"Where did she learn it," wondered Romney, "and she never at Court?"

For Peggy the most trying period in the ordeal was when she was left standing alone while her cavalier, with gliding steps and deep bows, retreated to the centre of the room, where, sweeping a grave circle with his rapier, he faced about and again advanced toward her with the proud peacock-motion that gave the dance its name. At first she had not the courage to look up to his face at all, but kept her eyes fixed upon the scarlet cross-bands embroidered with gold across his breast and the jewel-studded hilt of his rapier.

Apparently His Excellency found the view of her eyelashes and lowered lids unsatisfactory, for as they paced down the room between the rows of gallants he compelled her to look up by asking how she liked Virginia.

"Virginia much, but Virginians more," she answered.

"That is doubly a compliment, coming from a dweller across the border," said the Governor, with a smile. "For our part, whatever quarrels we may have with the men of your province, we are forced to lower our swords before its women. Beauty is the David who slays his tens of thousands, where strength, like Saul, counts its thousands only. It is not every one," he added, with a look which older men permit themselves and call impertinence in a youth, – "it is not every one who can move in a ball-room as if it were her birthright to be admired."

"Thank you," said Peggy, and then blushed crimson. "What a dolt I am," she thought; "as if he meant me!"

To cover her confusion she fixed her eyes upon a soldierly man at the head of the room.

"Can you, who know every one, tell me," she asked, "who is the cavalier who dances with an abstracted air, as though his thoughts were fixed on serious subjects, and his mind only permitted his body to dance on condition that it made no demand on his attention?"

"Ah, you mean Councillor Claiborne."

"Not Master William Claiborne?"

"Why not?"

"Why – why – " stammered Peggy, "I thought he would look like a cut-throat or a pirate."

The Governor laughed so loud that every one turned and wondered what the girl talking with him could have said that was so mightily clever, and thus her blunder did the new-comer more good in social repute than the finest wit.

"So the Maryland picture of poor Claiborne supplies him with all the attributes of the devil, except the horns and hoof? And you would never have known him as different from half the worthies here to-night. Well, I'll tell you privately what Master William Claiborne really is, – a good friend, an able secretary of the Council, and a damned obstinate enemy. When Baltimore undertook to oust him from Kent Island he might better have thrust his hand into a nest of live wasps. Ah, what? Our turn again. Why, young lady, your talk is so beguiling I had quite lost myself."

Peggy smiled behind her fan at the Governor's notion that it was she who had done the talking. She wished – she did wish Christopher could have heard him say it, though. But Christopher, when she begged him to be present at the dance, had shaken his head and answered that he should not know how to carry himself at a ball. Peggy, remembering her mother's stories of Christopher at court, and how Queen Henrietta had asked to have him presented to her as the finest gallant at Buckingham Palace, had fallen to crying then. Even now, following her little vanity came a great rush of pity and tenderness that brought the quick tears, and made her glad when the dance was ended, and Sir William, bowing low over her hand, led her to her seat with a kiss.

"Uncle William has resigned her at last," said the Governor's niece, who was talking with Romney in a corner under the musician's balcony. "Do you admire her as much as the other men do?"

"Her?" asked Romney, with a fine show of indifference.

"Mistress Neville, I mean, that they all talk of as if nothing like her was ever seen before."

"Do they?"

"Ay, Master Lawrence says she lights the hall more than all the candles, while Colonel Payne says that her dancing is poetry and her talk is music."

"Indeed!"

"Ay, and Captain Snow is worst of all, for he follows her about with his eyes opened twice as big as usual, lest he lose a single glance. If you doubt me, look at Polly Claiborne, who thought she had him safely landed for a husband, and now sees him drifting in the tow of another bark. She is furious."

"She looks calm enough."

"In the face, yes, but look at her hands; they are wringing that unlucky lace kerchief as if 'twere her rival's neck. But you have not said what you think of this paragon."

"I was looking at you."

"Toward me, not at me, and ever and anon your eyes took a holiday and wandered off to the Beauty. Oh, it is fine to be a Beauty with a capital letter. Yet I think really it is more her manner that charms than her looks. She has the air of being so pleased with each man she meets, and so more than pleased that he finds pleasure in looking at her."

"She does."

"It looks like vanity. Say you not so?"

"It surely does – like coquetry, which is the very essence of vanity."

"'Tis well she hears you not."

"I will go over now, and you shall see me tell her so," Romney said, as a man joined them.

"It was a shrewd device; but it fails to deceive me," thought his companion. "He is in love, and he is jealous."

"It is like the days at old Romney Hall, is it not, sweetheart?" said the master of the house, standing beside his wife, as they watched the lines of men and maidens gliding down the length of the room, their gorgeous brocades and glistening jewels reflected as in a mirror in the polished floor.

"Ay," answered Elizabeth, "and the county of Devon could not show more pretty faces than are here to-night. Nancy Lynch is a beauty, and Kitty Lee has the loveliest crinkly hair."

"But Peggy is the queen of the ball," said Huntoon, with a satisfied nod. "See the saucy baggage smiling at her own reflection in the glass."

"I fear she is vain."

"No doubt, being pretty, and a woman."

"She is neglecting Romney."

"But is she not having a fine time! I vow it makes my slow, old blood dance to watch her."

"But it is Romney's dance, and he enjoys it not."

"And if the boy wants the moon, this being his birthnight, his mother must get it for him. See, Peggy is throwing a rose at Romney. It hit him squarely in the breast and she is smiling at him."

"Stupid!" said Elizabeth. "Why does he not ask her for the galliard?"

"He has; see how glum the others look. Call you that hospitality, to keep the best for himself?"

"Oh, the others were best occupied in talking with the girls. But no, they must hang about looking at Peggy, as though the sun rose and set over her shoulder."

Yet Elizabeth smiled.

Meanwhile Peggy, having had her fill of admiration, turned gracious and bethought herself of the other damsels. She would fain have persuaded some of her superfluous partners to betake themselves across the hall to where Polly Claiborne was sitting in solitude against the settle; but such curious creatures are men, that they prefer to hover on the frigid rim of the outermost circle of success rather than to bask in the welcoming smiles of the neglected.

One held Peggy's fan, another her kerchief, a third her roses, the ones Romney had gathered for her this afternoon, and now viewed with wrath, seeing them picked to pieces by the idle fingers of young Captain Richard Snow, who, having won a place in the inner line by her side, showed a determination not to abandon it before supper.

"Never before did I know that the Huntoons were selfish!" he was murmuring.

"That they could never be!" ejaculated Peggy, with anger in her voice.

"Yet they have kept you to themselves for a whole year, you that should have shone like the sun over all Virginia."

"Poor Virginia!" mocked Peggy; "she has indeed been sadly cheated."

"You need not shine long to warm the province," said a second gallant, "since you have melted Snow in a single evening."

"Ah," answered Peggy, "snow in this part of the world never stays long, but," with a side glance under her lashes, "it is lovely while it lasts;" then catching too a self-satisfied smile upon the Captain's face, she added pertly, "but somewhat soft."

The Captain colored and glowered at his rival. "It is a misfortune," he said, stiffly, "to have a name that lends itself to jests."

"Oh," said Peggy, feeling that she had taken a liberty and anxious to make amends, "I do admire your name much."

"Really!"

"Really and truly."

"You have only to take it; I assure you it is quite at your service."

At this a shout of laughter went up from the circle of men about.

"What is the jest?" asked Romney, joining the group from which he had been vainly striving to abstract his eyes and interest.

"Why, an offer of marriage from Snow, which Mistress Neville has not yet answered."

Romney showed his vexation by tapping with his foot on the floor and biting his lip.

"Yes," added another, "we are all waiting eagerly to try our own chance."

"I am sorry," said Romney, stiffly, "to cut short your lottery, but my mother has sent me to conduct Mistress Neville to the supper-table, and begs that you gentlemen will find partners."

Peggy, knowing that she was not behaving well, was incensed with Romney for showing that he knew it too.

"The hero of a birthnight is no more to be denied than the King himself," she said, turning for a last smile at her court. Then as soon as they were out of hearing, "Romney, what is the matter? Have I a black smooch on my nose, or did I talk too much or laugh too loud that you look so – so – so righteously disapproving?"

"If you are satisfied with your conduct I shall not presume to disapprove."

"If I were satisfied with my conduct I should not care a halfpenny whether you disapproved or not. It's just because I am not satisfied in the least that it makes me so vexed that you do presume to disapprove. See you not why I cannot bear to have you think ill of me?"

Romney's heart beat thick and fast.

"Why, Peggy? Will you not tell me why?"

"Because if you do your mother will, and then I should have only your father for my friend, and by and by – perhaps – who knows? – he would give me up too."

Romney's spirits, which had risen to boiling point at her question, sank to freezing at her answer. The lights seemed to fade out of the hundred candles and leave the hall gloomy; he heard the fiddles scraping out the tune of "Oil of Barley," and he hated the music ever after. In silence he stalked on to the door of the supper-room. Within was a merry din of talk and laughter.

"Come, Peggy," said the hostess, "I was looking for you. We are waiting for you to cut the birthday cakes. Good friends all," she continued, turning to the company, "we have here two birthday cakes, and in each lies hid one half of a gimmal ring, which, as you know, is made of two rings that do fit together to form one. On the man's ring is inscribed 'to get,' and on the maid's, 'her,' and being united they read 'together.' Come, Peggy, cut and choose first lot for the maid's ring!"

Amid much shouting and laughter the lots were cast, and when it was found that the lucky numbers had been drawn by Mistress Neville and Captain Snow, all the company save one found the result vastly diverting. The Captain fastened his half conspicuously over his breast, and Peggy mischievously slipped hers upon the marriage finger.

Humphrey Huntoon, seeing the gathering cloud on Romney's brow, filled a goblet from the great punch-bowl which stood in the centre of the table flanked by candelabra bearing twenty candles each.

"A toast, my boy! a toast!" he called out, and under his breath he murmured, "Forget not that to-night you are host first and lover afterward."

Romney colored but took the goblet, raised it and said, bowing to all corners of the room, —

"To my guests, one and all!"

"I give you 'The Ladies of Virginia!'" called Colonel Payne.

"Here's to Maryland! Confusion to her men, but long life to her women!" It was Claiborne who spoke, and Captain Snow capped the toast by clinking his new ring against his goblet and crying, "I drink to Her!"

Peggy, seeing Romney's face darken again, took her courage in both hands and with it her goblet, which she lifted, saying in a soft voice which could yet be heard over all the room, —

"To Master and Mistress Huntoon, the kindest hostess and the noblest host, and – " here she stretched out her hand to Romney, "to the hero of the night, the best comrade in the world!"

A chorus of "Long life to them all!" greeted the toast, and the goblets clinked merrily; but to Romney it might have been water or wine or poison they were drinking, for all he knew or cared.

At last, when supper was ended Sir William Berkeley rose in his place, and with a solemnity quite different from his jovial manner of the evening hitherto he said, "One last toast, and we will, if you please, drink it standing. The King, God bless him!"

Fifty men sprang to their feet, fifty goblets flashed in air. Then utter silence fell. It was as if the shadow of the scaffold at Whitehall already cast its gloom over the loyal hearts of the colonial cavaliers.

The guests broke up into little groups of two and three and wandered back to the dancing-hall, where the fiddles were still working away for dear life at the strains of "The Jovial Beggar" and "Joan's Ale is New." The long lines of reel and brantle formed again, and the dancers refused to give over their merry-making till the gray dawn came peeping in at the window, turning the yellow candlelight to an insignificant glimmer, and hinting of the approaching day and its humdrum duties.

As the guests, one by one, came up to bid their hosts a good-night, which might more appropriately have been a good-morning, Master Claiborne drew Huntoon aside a moment, asking, —

"Will you be at home to-morrow – I mean to-day?"

"Ay."

"Then I may come to see you?"

"Why not stay now, since 'tis already day?"

"Because there be others I must see first, but I will be back before noon."

"And I glad as always to see you, but too sleepy, I fear, to give heed to any business."

"Then get your sleep before, for it is business of moment touching which we need your aid and counsel."

Before Huntoon could answer, another guest claimed his attention, and he followed to the door to help the ladies, who had donned their hoods and safeguards, to mount their horses or embark in the boats.

As they rode or sailed away into the gray dawn, Peggy, wrapped in her red cloak, stood with Romney watching them from the porch.

"It has been such a beautiful ball!" she sighed.

"You think so?"

"Of course I do; but then, you see, I never saw a real, big ball before. Do you think they are all like that?"

"To girls like you, yes, and I suppose to men like me."

"But there are so few men like you."

Romney's eyes looked a question.

"So persistent and so jealous and so – dear – "

With this Peggy pulled the ring off her finger and, tossing it lightly toward the lad, whispered, —

"Catch! and keep it if you can! It is my birthday gift."

"I take the dare and I take the gift, and I will yet take something else. So there, Peggy!"

But ere he had finished she had vanished up the stairway and the ball was over.

CHAPTER XXI

A ROOTED SORROW

Before the last guest had taken his departure from Romney the red sun came bobbing up across the river and shot his rays in at the window.

There is a sarcastic common-sense about the morning sun on such occasions. "Was it all worth while?" he seems to ask. "Consider the labor of preparation, the rushing about of the servants, the hours that my lady spent before her mirror with patch and powder-puff, the effort my fine gentleman expended upon his ruffles and falling bands. Then the occasion itself, the weary feet that trod the measure long after the toilsome pleasure had ceased to please, the lips that murmured sentiment knowing it was nonsense, the eyes that reversed the old moral maxim and strove to beam and not to see – Reflect upon all these and then sum up the aftermath, – the disordered rooms, the guttering candles, the faded flowers, the regretted vows, the heavy eyelids, the aching heads. Now, was it all worth while?"

The answer of the overnight revellers would doubtless depend chiefly on age and temperament. Young men and maidens would reply that it was none of the sun's business; that he had never been at a ball, and did not know what he was talking about, and for themselves they preferred to reserve their confidences for the sympathetic moon, who, being so much younger than the sun, could better understand youthful experiences and emotions.

Certainly that is what Romney Huntoon would have said. The commonplace day annoyed him. His mood was too sentimental for its searching light. He had slept little, and now at near noon hung about the foot of the stairway wondering at what time it would occur to Mistress Margaret Neville to come down.

When she did appear disappointment was in store for him. She seemed to have forgotten wholly that little scene on the terrace, and when he held out his hand with her ring, that blessed little ring upon it, she only courtesied and asked if his mother were yet down stairs.

At breakfast it was little better: she raved over Colonel Theophilus Payne, praised the bearing of Councillor Claiborne, said how she doted upon army men, commended the curls of one cavalier and the bearing of another, – all as if no such youth as Romney Huntoon had ever crossed her path.

Romney avowed his intention of spending the afternoon in his boat on the river. Peggy thought it an excellent plan, and purposed retiring to her room unless Mistress Huntoon had need of her.

Mistress Huntoon had no need of her. In fact, in reviewing last night's events she felt that Peggy had treated her son rather badly, and she was inclined to make the culprit feel it, too. It must be admitted that justice is never so unrelenting as when Rhadamanthus has been up overnight. On another occasion excuses might have been found for the girl, but this morning she was pronounced unquestionably vain and presumably heartless, – in short, Elizabeth Huntoon was out of temper.

It was not much better with her husband. He was uneasy over the approaching visit of William Claiborne, and annoyed with himself that he had not had the wit to devise an excuse. He knew well Claiborne's insubordinate temper, and had no mind to be drawn into any of his schemes.

Peggy alone worked away at her stitching in exasperating content. At length Romney could bear it no longer. He rose, thrust his hands into his pockets and rushed out, opening the door with his head as he went, like a goat butting a wall.

Peggy smiled, and the smile brought a frown to the face of her hostess.

"Romney is not over well this morning, I fear," said his mother.

"I thought he was not behaving well – I mean not behaving as if he were well."

"He hath much to try him."

" That is hard to believe, in this beautiful home and with thee for a mother."

Elizabeth tapped the floor with her slipper.

"'Twere well for young men if a mother's love sufficed them."

"Ho! ho!" laughed Humphrey, roused from his abstraction by the tilt between the two women. "Faith, good wife, I felt the need of another love than my mother's, and I look not to see Romney more filial than I."

"Oh, you may make a jest of me," began Elizabeth, stiffly; but there was a catch in her voice which led Peggy to throw down her netting, and run across the room to kneel beside her. "I need a mother's love more than any," she whispered.

Elizabeth's anger weakened.

"Tell me where Romney has gone and I will follow and strive to make my peace."

For answer Mistress Huntoon pointed through the window to where Romney sat on the edge of the wharf vexing the placid breast of the York River by a volley of pebbles, flipped between his thumb and forefinger.

As the boy sat thus idly occupied, his hand full of pebbles, his head full of bitter thoughts, his heart of a curious numbness, he felt a light touch on his shoulder, but he did not turn.

"Master Huntoon!"

No answer.

"Romney!"

"Ay."

"Of what art thou thinking?"

"Nothing."

"And what dost thou think of when thou art thinking of nothing?"

"A woman's promise."

"Hath some woman promised thee aught and failed thee?"

"Ay, it comes to the same thing. Eyes may speak promises as well as lips."

"Oh, yes, eyes may say a great deal, especially when they are angry eyes and look out from under drawn brows. I should scarce think any maid would dare wed a man with eyes that could look black when their color by nature is blue."

Clever Peggy to shift the ground of attack! Silly Romney to fall into the trap!

"I am not angry."

"Yes you are, and have been all the morning in a temper. I felt quite sorry for your mother, she was so shamed by it."

"What said she?"

"Oh, that you were not well, which is what mothers always say when their son's actions do them no credit."

"If my temper did me no credit, who drove me to it?"

Peggy raised her eyebrows, puckered her pretty lips, and looked straight up into the sky as if striving to solve a riddle.

"For my life I cannot guess," she said at last, "unless – unless it was that wretched woman who broke her promise."

"Thou hast keen insight for one of thy years."

"Then it was she!"

"It was no other."

"Tell me her name, that I may go to her and denounce her to her face."

"Strangers know her as Mistress Margaret Neville. To her friends she is plain Peggy. Now denounce her to her face if thou wilt."

Tripping to the edge of the bank, the girl bent over till she could catch the reflection of her curls and dancing eyes in the water.

"Plain Peggy," she said, shaking her finger at the image below with a wicked smile, "you must be a bad baggage. It seems you have broken your promise to marry a gentleman here, and such a perfect gentleman! he says so himself, – one who never gets angry, never butts with his head at doors, never shames his mother. Why, plain Peggy, you must be a fool to lose such a chance; but since you have thrown away such a treasure, I trust you will meet the punishment you do deserve, and that he will go away and never —never– never speak – to you again!"