полная версия

полная версияПолная версия

The History of the First West India Regiment

The first effect produced by the arrival of this succour, was the retiring of the enemy from their advanced position on Fairbairn's Ridge to the Vigie, where they now collected the whole of their strength. From this post Major-General Irving determined to dislodge them; and, on the night of the 1st of October, the troops marched for that purpose. One column, consisting of 750 men, under Lieutenant-Colonel Strutt, marched by the high road and took post upon Calder Ridge, on the east of the Vigie, about three in the morning. A second column, consisting of 900 men, under Brigadier-General Myers, crossed the Warawarrow River, and detached one party to proceed round by Calliaqua, and another to move up the valley, and climb the heights near Joseph Dubuc's. With this last force was Malcolm's Corps; and, to gain the point to which they were directed, it was necessary to cross a deep rivulet and ascend a steep hill covered with bushes and wood. In doing this it suffered a heavy loss, both of officers and men, from the enemy, who fired upon it almost in security under shelter of the bushes. The British, however, still pressed on, and at length arrived on the top of the Marriaqua or Vigie Ridge. During the ascent of the hill, Malcolm's Corps lost one man killed and two wounded.

In the meantime, the remainder of the second column were struggling in vain to reach the summit of the same ridge; at a point where the enemy had strongly occupied a thick wood, and thrown up a small work. Though the opposing forces were within fifty paces of each other, not an inch of ground was won on either side. Firing commenced at seven in the morning, and was kept up till nightfall. All this time the British were exposed to a violent tropical downpour of rain, which rendered the abrupt declivity so slippery that it was almost impossible to maintain a foothold on it; and, finding he could make no impression on the enemy, the general, about 7 p.m., gave orders for the troops to retire.

During the night, the enemy, from some unknown cause, abandoned the Vigie, and that so hastily that they left behind them, undestroyed, both guns and ammunition. They continued their retreat till they reached the windward part of the island, and the British in their turn advanced. For the remainder of the year, the troops were employed in circumscribing, within as narrow limits as possible, the French and their Carib allies; and, though great hardships were endured, no engagement worthy of note took place.

CHAPTER VII.

MAJOR-GENERAL WHYTE'S REGIMENT OF FOOT, 1795

The terrible mortality which thinned the ranks of the British troops in the West Indies, induced the British Ministers to think of reinforcing the army with men better calculated to resist the influence of the climate. The West India Governors were instructed, therefore, in 1795, to bring forward in their respective legislatures a project for raising five black regiments, consisting of 500 men each, to become a permanent branch of the military establishment. There were already several black corps in existence, for Mr. Dundas, during a debate in the House of Commons on the West India Expedition, on the 28th of April, 1795, said that "the West India Army of Europeans and Creoles consisted of 3000 militia and 6000 blacks."19

These black corps were distributed amongst the various islands, and were the Carolina Corps, Malcolm's or the Royal Rangers, the Island Rangers (Martinique), the St. Vincent Rangers, the Black Rangers (Grenada), Angus' Black Corps (Grenada), the Tobago Blacks, and the Dominica Rangers. Some of them, notably the Carolina Corps, Malcolm's Corps, and the St. Vincent Rangers,20 were paid by the Imperial Government, and were consequently Imperial troops; although none of the corps appeared in any Army List, nor were appointments thereto and promotions therein notified in the London Gazette.

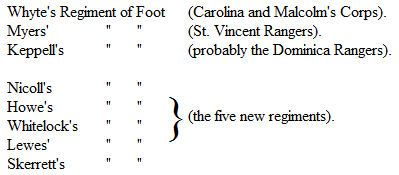

The five black regiments, now proposed to be raised, were to be in addition to those small black corps already in Imperial pay, and which were to be blended into three permanent regiments. Consequently, in the Army List dated March 11th, 1796, showing the state of the army in 1795,21 we find the following eight corps, indexed under the heading of "Regiments raised to serve in the West Indies:"

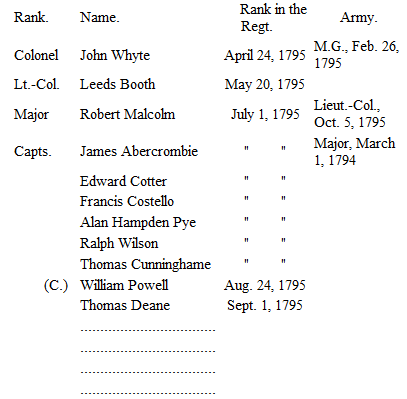

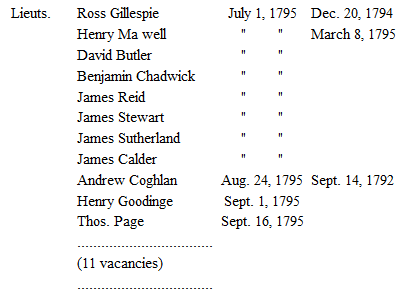

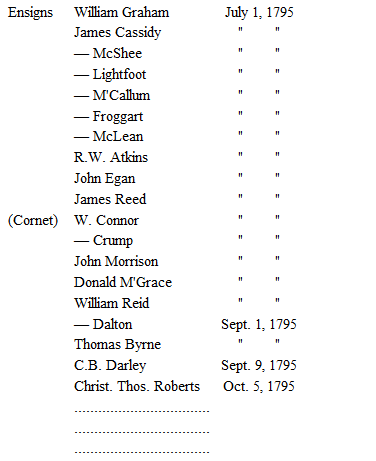

Major-General Whyte's regiment was called into existence by the Gazette of the 2nd of May, 1795; Major-General John Whyte, from the 6th Foot, being appointed colonel. On the 20th of May, Major Leeds Booth, from the 32nd Foot, was appointed lieutenant-colonel; and other officers were rapidly gazetted to it. On the 8th of August, Captain Robert Malcolm, of the 41st Foot, was promoted major in Whyte's regiment. The following is the list of officers appointed to the regiment in 1795:

Major-General Whyte's Regiment of Foot.

It was intended that each of these regiments raised for service in the West Indies should have a cavalry troop, and in the London Gazette are the following:

Major-General Whyte's Regiment of FootAugust 1, 1795 Lieutenant – Powell, from the 8th Foot, to be Lieutenant of Cavalry.

August 29 Lieutenant – Powell, Lieutenant of Cavalry, to be Captain of Cavalry.

July 11 Acting Adjutant – Connor, from Lieutenant-Colonel McDonnel's regiment, to be Cornet.

But this idea was soon abandoned, and in 1797 the cavalry troop disappeared.

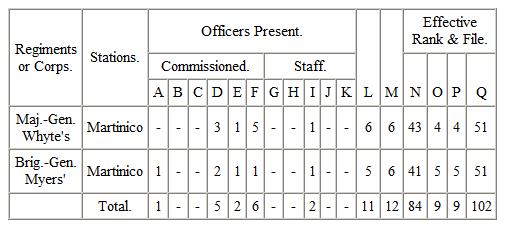

The 1st West India Regiment (for so it was at once styled in the West Indies, although in the Army List and the London Gazette, the designation "Major-General Whyte's Regiment of Foot" was not discontinued until February, 1798) first appears in the "Monthly Return for the Windward, Leeward, and Caribee Islands," in September, 1795, as follows:

A: Colonel.

B: Lieut. – Colonel.

C: Majors.

D: Captains.

E: Lieutenants.

F: Ensigns.

G: Chaplain.

H: Adjutant.

I: Quarter-Master.

J: Surgeon.

K: Mate.

L: Sergeants Present.

M: Drummers Present.

N: Present, fit for duty.

O: Sick.

P: Recruiting.

Q: Total.

and the following note is, in the same Return, appended to the state of the company of the "Black Carolina Corps," which was in Grenada; the other two companies having remained in Martinique since their removal there from St. Lucia at the end of April, 1795. "This corps has been reformed, and fifty of the men, who were fit for service, have been drafted into the 1st New West India Regiment. When the remainder of the corps can be collected together, it is possible a few more may be found fit for service."

Major-General Whyte's, or the 1st West India Regiment, remained at Martinique, without any further accession to its strength than these fifty men from the Carolina Corps, till December, 1795.

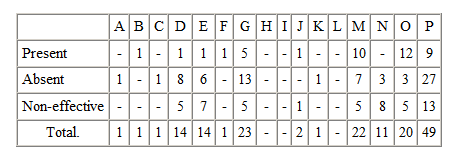

In the "Muster Roll of His Majesty's 1st West India Regiment of Foot, for 183 days, from the 25th of June to the 24th of December, 1795, inclusive," the list of officers is given as already shown. Captain James Abercrombie, Lieutenants David Butler, Benjamin Chadwick, and James Sutherland are shown as "drowned on passage," and the following note is added: "Some few of the dates of enlistments and enrolments of the non-commissioned officers and drummers may not probably be quite exact, and some others may have been engaged in England not down on the muster roll, all the regimental books, attestation papers, etc., having been left in possession of the paymaster, Brevet-Major Abercrombie (no adjutant at that time being appointed), who was lost in December or January last on board the Robert and William transport, No. 44, on the voyage to this country." The non-commissioned officers and drummers were Europeans, one sergeant and three corporals being shown as "sick and absent in England" in this roll; and, in the next, a drummer is similarly shown. The roll is signed by Leeds Booth, Lieutenant-Colonel; Ed. S. Cotter, Captain and Paymaster; and Thomas Holbrook, Acting Adjutant. The following is the proof table:

A: Colonel.

B: Lieut. – Colonel.

C: Major.

D: Captains.

E: Lieutenants.

F: Cornets.

G: Ensigns.

H. Adjutant.

I. Chaplain.

J. Quartermaster.

K. Surgeon.

L. Mate.

M. Sergeants.

N. Corporals.

O. Drummers.

P. Privates.

Although it was intended that the privates of West India regiments should be black, yet, apparently, white men were not prohibited from serving in the ranks; for, in later muster rolls, two or three privates are shown as "enrolled in England," and one of these is afterwards shown as "transferred to 60th." A volunteer, David Scott, who joined 29th May, 1797, was also promoted ensign in November of that year. These enrolments of Europeans only occur in the first three years of the regiment's existence, and negro privates were available for promotion to, at least, the rank of corporal very early; for a Private John Lafontaine, who was promoted corporal, is shown in the muster roll terminating December 24th, 1796, as "claimed as a slave." The pay of a private in a West India regiment was then sixpence per diem.

CHAPTER VIII.

THE CAPTURE OF ST. LUCIA, 1796

In January, 1796, the company of Malcolm's Royal Rangers that was at St. Vincent was moved to St. Christopher; the other company still remained at Martinique, and both, in April, 1796, were selected to take part in the expedition to St. Lucia. "That island could then muster for its defence about 2000 well-disciplined black soldiers, a number of less effective blacks, and some hundred whites, who held positions both naturally and artificially strong, and were plentifully supplied with artillery, ammunition, and stores. The post on which the Republicans chiefly confided for their defence was that of Morne Fortune. It is situated on the western side of the island, between the rivers of the Carenage and the Grand Cul de Sac, which empty their waters into bays bearing the same name. Difficult of access by nature, it had been rendered still more so by various works. In aid of this they had also fortified others of the mornes, or eminences, in its vicinity. The whole of this position, embracing a considerable extent of ground, it was of the utmost importance to invest closely, with as little delay as possible, that the enemy might not escape into the rugged country of the interior, and thus be in a condition to carry on a protracted and harassing war, which experience had already more than once proved to be highly detrimental to an unseasoned invading force.

"To accomplish this desirable purpose, the British general determined to direct his troops on three points, two of them to the north, and the third to the south of Morne Fortune. The first division was to land most to the north, in Longueville Bay, covered by several vessels, which were intended to silence the batteries on Pigeon Island. Choc Bay was the spot where the centre division was to be put on shore; and the third was to disembark at Ance la Raye, some distance to the southward of the hostile post."22

The fleet with the troops destined for the attack of St. Lucia, under Sir Ralph Abercromby, sailed from Carlisle Bay, Barbados, on the 22nd of April, and anchored in Marin Bay, Martinique, on the evening of the 23rd, where Malcolm's Rangers joined the force, sailing for St. Lucia on the 26th. The troops arrived off that island on the evening of the same day, and 1700 men, under the command of Major-General Campbell, composing the first division, were immediately landed in Longueville Bay; without encountering any further opposition than a few shots from the battery on Pigeon Island, the fire of which was speedily silenced by that of the ships.

A strong current had driven the transports so far to the leeward that it was not practicable to land the centre division till the following morning. Major-General Campbell was meanwhile on his march, and his progress was only feebly opposed by about 500 of the enemy, who ultimately retired from Angier's Plantation to Morne Chabot, and allowed him to effect a junction with the centre division. The current having acted still more powerfully on the vessels which conveyed the third division, under Brigadier-General Morshead, two or three days elapsed before the disembarkation in Ance la Raye could be entirely executed. The troops at length took up their appointed station, and thus held Morne Fortune invested on its southern side.

To complete the investment on the northern quarter it was necessary to obtain possession of Morne Chabot, which was one of the strongest posts in the vicinity of Morne Fortune. At midnight of the 27th, therefore, two columns, under Brigadier-Generals Moore and Hope, were despatched to attack the Morne on two opposite sides; and, by this means, not only to carry the position, but likewise to prevent the escape of the troops by which it was defended. This plan, the complete success of which would have materially diminished the strength of the Republican force, was in part rendered abortive by a miscalculation of time. The column of Brigadier-General Moore, consisting of seven companies of the 53rd Regiment, 100 of Malcolm's Rangers, and 50 of Lowenstein's,23 advanced by the most circuitous route; while Brigadier-General Hope, with 350 men of the 57th, 150 of Malcolm's Rangers, and 50 of Lowenstein's, took the shorter road. Misinformed by the guides, Brigadier-General Moore's column fell in, an hour and a half sooner than it had expected, with the advanced picket of the enemy, who were thus put on their guard. At the moment when they were discovered, the troops, in consequence of the narrowness of the road, were marching in single file, and to halt them was impossible. In this state of things their leader resolved not to give his opponents time to recollect themselves, but to fall on them with his single division. The spirit of the soldiers fully justified the gallant resolution of their commander. Having been formed as speedily as the ruggedness of the ground would admit of, they proceeded to the assault. The Republicans made a stubborn resistance, but it was an unavailing one, as they were finally driven from the Morne with considerable loss. Nevertheless, as the second column did not arrive till the combat was over, the fugitives succeeded in making good their retreat. On the following day the victors also occupied Morne Duchasseaux, which is situated in rear of Morne Fortune.

In the hope of obtaining some advantage to counterbalance this misfortune, the enemy, on the 1st of May, made a brisk attack on the advanced post of grenadiers commanded by Lieutenant-Colonel MacDonald, of the 55th Regiment. They were, however, repulsed with much slaughter, though not till forty or fifty men, and several officers, were killed or wounded on the side of the British, among them being Captain Coghlan, 1st West India Regiment, attached to the 48th Regiment, who was wounded.

At the south side of the Morne Fortune the enemy had erected batteries, which precluded any vessels from entering into the bay of the Grand Cul de Sac. To open this bay to our fleet was an object of much importance, as at present it was necessary to convey the artillery and stores from a great distance, which could not be done without the previous labour of opening roads through an almost impracticable country. It was, therefore, resolved to make an attempt on these batteries. The principal attack was to be conducted by Major-General Morshead, whose division, in two columns, was to pass the river of the Grand Cul de Sac; the columns of the right at Cools, and that of the left at the point where the waters of the stream are discharged into the bay. To second this force, Brigadier-General Hope, on the night of the 2nd of May, was to advance from Morne Chabot with 350 men of the 42nd Regiment, the light company of the 57th, and part of Malcolm's Rangers, the whole being supported by the 55th Regiment, which was posted at Ferrands. A part of the squadron was likewise to lend its assistance, by keeping up a cannonade on the works of the enemy. Before the time arrived for putting this plan into execution, Major-General Morshead was taken ill, and the command devolved upon Brigadier-General Perryn. No change, however, took place in the arrangements which had been formed.

"At dawn of day, the division under Brigadier-General Hope began to accomplish its part of the service by carrying the battery Seche, which was situated within a short distance of the works of Morne Fortune. The assailants suffered so little in the assault, that they would scarcely have had anything to regret, had it not been for the fall of the gallant Lieutenant-Colonel Malcolm.24 On the south side of the Morne, and at the extremity of the line of attack, Colonel Riddel, who led the column of the left, made himself master of the battery of Chapuis, and established himself there. Had the remainder of the project been as well executed, the proposed object would have been completely attained. Unfortunately, however, from some unexplained cause, the division which was the connecting link of the whole, that which was entrusted to Brigadier-General Perryn, did not perform its allotted part, by crossing the river at Cools. The consequence of this was that the victorious columns were left insulated, and would have been exposed to no trivial danger, had the enemy felt a sufficient reliance upon their own strength to incite them to act with the requisite promptitude and vigour. Painful, therefore, as it was to retire before a routed foe, the British troops were compelled to abandon the batteries which they had won, and to fall back upon their original stations. The ships at the same time returned to their former anchorage. Our loss on this occasion was 105 men; of whom only a very few were among the slain."

The Vigie was now the only post occupied by the enemy in the vicinity of Morne Fortune, and this was attacked by the 31st Regiment on the night of May 7th; the assault, however, being repulsed with a loss of 200 men. The main position was now invested by regular siege works, and the task which the British had to perform was attended with no small difficulty. "The country itself was of the most inaccessible kind, the chain of investment was ten miles in extent, all the roads that were necessary were to be made, of carriages there were none, horses were scarce, and the Republicans had been industrious in availing themselves of all the natural obstacles to our progress, and in creating as many others as their ingenuity could contrive." Malcolm's Corps rendered good service on these works, and the men being better able to stand the fatigue and exposure than Europeans, were constantly employed.

By May 16th, the first parallel was completed, and on the morning of the 24th, the 27th Regiment, supported by the 53rd and 57th, succeeded in effecting a lodgment within 500 yards of the fort. The Governor, acknowledging that further resistance was futile, demanded a suspension of hostilities; terms of surrender were agreed upon, and on May 26th, 2000 men marched out as prisoners of war. One hundred pieces of ordnance, ten vessels, and large stores of ammunition fell into the hands of the British.

Sir Ralph Abercromby sailed from St. Lucia on the 4th of June to the relief of Grenada and St. Vincent, leaving Brigadier-General Moore for the pacification of the first island with the 31st, 44th, 38th, and 55th Regiments, O'Meara's corps of Rangers,25 and the German Yagers.

CHAPTER IX.

THE RELIEF OF GRENADA, 1796 – THE REPULSE AT PORTO RICO, 1797

Grenada, like St. Vincent, had been ravaged by the French and insurgent slaves since March, 1795, and the relief of that island was one of the first cares of Sir R. Abercromby. On leaving St. Lucia, the division of the troops intended for Grenada was ordered to rendezvous at Cariacou, one of the Grenadines; there Sir Ralph Abercromby met Major-General Nicolls, then commanding in Grenada, and arranged with him the general plan of operations. Before, however, those operations are described, it will be necessary to go back to the month of March, 1796, when a company of the Carolina Corps arrived in Grenada from Martinique, with detachments from the 8th, 63rd, and 3rd Regiments, under Major-General Nicolls.

Shortly before the arrival of this reinforcement, the French and insurgents had compelled the British to evacuate Pilot Hill, in the neighbourhood of Grenville, and had taken up a strong position at Port Royal. On the 23rd of March, Major-General Nicolls landed to the south of Port Royal; during the night the guns were got in position, and at daybreak opened on the enemy's works. The post occupied by the enemy was a hill of very steep ascent, particularly towards the summit, upon which a fort was constructed, and furnished with four six-pounders and some swivels. The first object of the British commander was to gain a position between the enemy and the open country, and thus leave them no alternative but to surrender at discretion, or precipitate themselves over a high cliff; but they had established themselves so strongly to protect their right that this failed. In the meantime two large vessels full of troops to reinforce the enemy arrived in the bay under Port Royal, from Guadaloupe; and Brigadier-General Nicolls found it necessary to storm the enemy's post without further delay. The troops employed in this service were detachments from the 3rd, 29th, and 63rd Regiments, under Brigadier-General Campbell; at the same time, 50 men of the 88th, with the company of the Carolina Corps, Colonel Webster's Black Rangers, and Angus' Black Corps, moved against the enemy's right flank, to dislodge some strong parties which were posted on the heights.

Owing to the difficult nature of the ground, it was nearly two hours before the latter column could reach the enemy, when a heavy fire commenced on both sides. The ascent was steep and difficult, encumbered with rocks and loose stones and covered with dense bush. From the summit of the ridge the enemy poured in a destructive fire, to which the British could only reply at a great disadvantage, and, after losing heavily, the column commenced to retire. Observing this retrograde movement, Major-General Nicolls sent the 8th Regiment in support and ordered Brigadier-General Campbell to proceed to the assault of the redoubt.

Repulsed at the first attempt the troops again pushed on, at length gained the summit of the ridge, drove the enemy into their redoubt and scrambled in after them through the embrasures. The enemy then fled in all directions, some threw themselves down the precipices, whilst others tried to escape down the hill through the thick underwood; but there was so heavy a fire kept up on them from above by the British that they were forced to attempt to escape along a valley, where they were charged by a detachment of the 17th Light Dragoons, and cut to pieces. The British loss consisted, in killed and wounded, of 110 Europeans and 40 of the various black corps. The Carolina Corps lost one man killed and six wounded.

Affairs were thus situated when the fall of St. Lucia enabled Sir R. Abercromby to send reinforcements to Grenada. The troops, with whom were Malcolm's Rangers, disembarked at Palmiste, on the 9th June, while Brigadier-General Campbell, with the troops already in the island, advanced from the windward side to take the enemy in rear. Captain Jossey, the commandant of the French troops at Goyave, near Palmiste, seeing that resistance must be unavailing, surrendered that post, with those of Mabouia and Dalincourt; but Fedon, the leader of the insurgent slaves, who knew he could expect no mercy, retired at the head of about 300 men to two strong and almost unapproachable positions, called Morne Quaquo and Ache's Camp, or Forêt Noir, in the mountains of the interior.