полная версия

полная версияEssays: Scientific, Political, and Speculative, Volume II

Even more obvious, if it be possible, does the radical character of this distinction become, on observing that from the simplest proposition of General Mechanics we may pass to the most complex proposition of Celestial Mechanics, without a break. We take a body moving at a uniform velocity, and commence with the proposition that it will continue so to move for ever. Next, we state the law of its accelerated motion in the same line, when subject to a uniform force. We further complicate the proposition by supposing the force to increase in consequence of approach towards an attracting body; and we may formulate a series of laws of acceleration, resulting from so many assumed laws of increasing attraction (of which the law of gravitation is one). Another factor may now be added by supposing the body to have motion in a direction other than that of the attracting body; and we may determine, according to the ratios of the supposed forces, whether its course will be hyperbolic, parabolic, elliptical, or circular – we may begin with this hypothetical additional force as infinitesimal, and formulate the varying results as it is little by little increased. The problem is complicated a degree more by taking into account the effects of a third force, acting in some other direction; and beginning with an infinitesimal amount of this force we may reach any amount. Similarly, by introducing factor after factor, each at first insensible in proportion to the rest, we arrive, through an infinity of gradations, at a combination of any complexity.

Thus, then, the Science which deals with the inter-action of hypothetical bodies in space, is absolutely continuous with General Mechanics. We have already seen that it is absolutely discontinuous with that account of the heavenly bodies which has been called Astronomy from the beginning. When these facts are recognized, it seems to me that there cannot remain a doubt respecting its true place in a classification of the Sciences.

REASONS FOR DISSENTING FROM THE PHILOSOPHY OF M. COMTE

[ Originally published in April 1864 as an appendix to the foregoing essay.]While the preceding pages were passing through the press, there appeared in the Revue des Deux Mondes for February 15th, 1864, an article on a late work of mine – First Principles. To M. Auguste Laugel, the writer of the article, I am much indebted for the careful exposition he has made of some of the leading views set forth in that work; and for the catholic and sympathetic spirit in which he has dealt with them. In one respect, however, M. Laugel conveys to his readers an erroneous impression – an impression doubtless derived from what appears to him adequate evidence, and doubtless expressed in perfect sincerity. M. Laugel describes me as being, in part, a follower of M. Comte. After describing the influence of M. Comte as traceable in the works of some other English writers, naming especially Mr. Mill and Mr. Buckle, he goes on to say that this influence, though not avowed, is easily recognizable in the work he is about to make known; and in several places throughout his review, there are remarks having the same implication. I greatly regret having to take exception to anything said by a critic so candid and so able. But the Revue des Deux Mondes circulates widely in England, as well as elsewhere; and finding that there exists in some minds, both here and in America, an impression similar to that entertained by M. Laugel – an impression likely to be confirmed by his statement – it appears to me needful to meet it.

Two causes of quite different kinds, have conspired to diffuse the erroneous belief that M. Comte is an accepted exponent of scientific opinion. His bitterest foes and his closest friends, have unconsciously joined in propagating it. On the one hand, M. Comte having designated by the term “Positive Philosophy” all that definitely-established knowledge which men of science have been gradually organizing into a coherent body of doctrine; and having habitually placed this in opposition to the incoherent body of doctrine defended by theologians; it has become the habit of the theological party to think of the antagonist scientific party, under the title of “positivists.” And thus, from the habit of calling them “positivists,” there has grown up the assumption that they call themselves “positivists,” and that they are disciples of M. Comte. On the other hand, those who have accepted M. Comte’s system, and believe it to be the philosophy of the future, have naturally been prone to see everywhere the signs of its progress; and wherever they have found opinions in harmony with it, have ascribed these opinions to the influence of its originator. It is always the tendency of discipleship to magnify the effects of the master’s teachings; and to credit the master with all the doctrines he teaches. In the minds of his followers, M. Comte’s name is associated with scientific thinking, which, in many cases, they first understood from his exposition of it. Influenced as they inevitably are by this association of ideas, they are reminded of M. Comte wherever they meet with thinking which corresponds, in some marked way, to M. Comte’s description of scientific thinking; and hence are apt to imagine him as introducing into other minds, the conceptions which he introduced into their minds. Such impressions are, however, in most cases quite unwarranted. That M. Comte has given a general exposition of the doctrine and method elaborated by Science, is true. But it is not true that the holders of this doctrine and followers of this method, are disciples of M. Comte. Neither their modes of inquiry nor their views concerning human knowledge in its nature and limits, are appreciably different from what they were before. If they are “positivists,” it is in the sense that all men of science have been more or less consistently “positivists;” and the applicability of M. Comte’s title to them, no more makes them his disciples, than does its applicability to men of science who lived and died before M. Comte wrote, make these his disciples. M. Comte himself by no means claims that which some of his adherents are apt, by implication, to claim for him. He says: – “Il y a, sans doute, beaucoup d’analogie entre ma philosophie positive et ce que les savans anglais entendent, depuis Newton surtout, par philosophie naturelle ;” (see Avertissement) and further on he indicates the “grand mouvement imprimé à l’esprit humain, il y a deux siècles, par l’action combinée des préceptes de Bacon, des conceptions de Descartes, et des découvertes de Galilée, comme le moment où l’esprit de la philosophie positive a commencé à se prononcer dans le monde.” That is to say, the general mode of thought and way of interpreting phenomena, which M. Comte calls “Positive Philosophy,” he recognizes as having been growing for two centuries; as having reached, when he wrote, a marked development; and as being the heritage of all men of science.

That which M. Comte proposed to do, was to give scientific thought and method a more definite embodiment and organization; and to apply it to the interpretation of classes of phenomena not previously dealt with in a scientific manner. The conception was a great one; and the endeavour to work it out was worthy of sympathy and applause. Some such conception was entertained by Bacon. He, too, aimed at the organization of the sciences; he, too, held that “Physics is the mother of all the sciences;” he, too, held that the sciences can be advanced only by combining them, and saw the nature of the required combination; he, too, held that moral and civil philosophy could not flourish when separated from their roots in natural philosophy; and thus he, too, had some idea of a social science growing out of physical science. But the state of knowledge in his day prevented any advance beyond the general conception: indeed, it was marvellous that he should have advanced so far. Instead of a vague, undefined conception, M. Comte has presented the world with a defined and highly-elaborated conception. In working out this conception he has shown remarkable breadth of view, great originality, immense fertility of thought, unusual powers of generalization. Considered apart from the question of its truth, his system of Positive Philosophy is a vast achievement. But after according to M. Comte high admiration for his conception, for his effort to realize it, and for the faculty he has shown in the effort to realize it, there remains the inquiry – Has he succeeded? A thinker who re-organizes the scientific method and knowledge of his age, and whose re-organization is accepted by his successors, may rightly be said to have such successors for his disciples. But successors who accept this method and knowledge of his age, minus his re-organization, are certainly not his disciples. How then stands the case with M. Comte? There are some few who receive his doctrines with but little reservation; and these are his disciples truly so called. There are others who regard with approval certain of his leading doctrines, but not the rest: these we may distinguish as partial adherents. There are others who reject all his distinctive doctrines; and these must be classed as his antagonists. The members of this class stand substantially in the same position as they would have done had he not written. Declining his re-organization of scientific doctrine, they possess this scientific doctrine in its pre-existing state, as the common heritage bequeathed by the past to the present; and their adhesion to this scientific doctrine in no sense implicates them with M. Comte. In this class stand the great body of men of science. And in this class I stand myself.

Coming thus to the personal part of the question, let me first specify those great general principles on which M. Comte is at one with preceding thinkers; and on which I am at one with M. Comte.

All knowledge is from experience, holds M. Comte; and this I also hold – hold it, indeed, in a wider sense than M. Comte; since, not only do I believe that all the ideas acquired by individuals, and consequently all the ideas transmitted by past generations, are thus derived; but I also contend that the very faculties by which they are acquired, are the products of accumulated and organized experiences received by ancestral races of beings (see Principles of Psychology ). But the doctrine that all knowledge is from experience, is not originated by M. Comte; nor is it claimed by him. He himself says – “Tous les bons esprits répètent, depuis Bacon, qu’il n’y a de connaissances réelles que celles qui reposent sur des faits observés.” And the elaboration and definite establishment of this doctrine, has been the special characteristic of the English school of Psychology. Nor am I aware that M. Comte, accepting this doctrine, has done anything to make it more certain, or give it greater definiteness. Indeed it was impossible for him to do so; since he repudiates that part of mental science by which alone this doctrine can be proved.

It is a further belief of M. Comte, that all knowledge is phenomenal or relative; and in this belief I entirely agree. But no one alleges that the relativity of all knowledge was first enunciated by M. Comte. Among others who have more or less consistently held this truth, Sir William Hamilton enumerates, Protagoras, Aristotle, St. Augustin, Boethius, Averroes, Albertus Magnus, Gerson, Leo Hebræus, Melancthon, Scaliger, Francis Piccolomini, Giordano Bruno, Campanella, Bacon, Spinoza, Newton, Kant. And Sir William Hamilton, in his “Philosophy of the Unconditioned,” first published in 1829, has given a scientific demonstration of this belief. Receiving it in common with other thinkers, from preceding thinkers, M. Comte has not, to my knowledge, advanced this belief. Nor indeed could he advance it, for the reason already given – he denies the possibility of that analysis of thought which discloses the relativity of all cognition.

M. Comte reprobates the interpretation of different classes of phenomena by assigning metaphysical entities as their causes; and I coincide in the opinion that the assumption of such separate entities, though convenient, if not indeed necessary, for purposes of thought, is, scientifically considered, illegitimate. This opinion is, in fact, a corollary from the last; and must stand or fall with it. But like the last it has been held with more or less consistency for generations. M. Comte himself quotes Newton’s favorite saying – “O! Physics, beware of Metaphysics!” Neither to this doctrine, any more than to the preceding doctrines, has M. Comte given a firmer basis. He has simply reasserted it; and it was out of the question for him to do more. In this case, as in the others, his denial of subjective psychology debarred him from proving that these metaphysical entities are mere symbolic conceptions which do not admit of verification.

Lastly, M. Comte believes in invariable natural laws – absolute uniformities of relation among phenomena. But very many before him have believed in them too. Long familiar even beyond the bounds of the scientific world, the proposition that there is an unchanging order in things, has, within the scientific world, held, for generations, the position of an established postulate: by some men of science recognized only as holding of inorganic phenomena; but recognized by other men of science, as universal. And M. Comte, accepting this doctrine from the past, has left it substantially as it was. Though he has asserted new uniformities, I do not think scientific men will admit that he has so demonstrated them, as to make the induction more certain; nor has he deductively established the doctrine, by showing that uniformity of relation is a necessary corollary from the persistence of force, as may readily be shown.

These, then, are the pre-established general truths with which M. Comte sets out – truths which cannot be regarded as distinctive of his philosophy. “But why,” it will perhaps be asked, “is it needful to point out this; seeing that no instructed reader supposes these truths to be peculiar to M. Comte?” I reply that though no disciple of M. Comte would deliberately claim them for him; and though no theological antagonist at all familiar with science and philosophy, supposes M. Comte to be the first propounder of them; yet there is so strong a tendency to associate any doctrines with the name of a conspicuous recent exponent of them, that false impressions are produced, even in spite of better knowledge. Of the need for making this reclamation, definite proof is at hand. In the No. of the Revue des Deux Mondes named at the commencement, may be found, on p. 936, the words – “Toute religion, comme toute philosophie, a la prétention de donner une explication de l’univers. La philosophie qui s’appelle positive se distingue de toutes les philosophies et de toutes les religions en ce qu’elle a renoncé à cette ambition de l’esprit humain;” and the remainder of the paragraph is devoted to explaining the doctrine of the relativity of knowledge. The next paragraph begins – “Tout imbu de ces idées, que nous exposons sans les discuter pour le moment, M. Spencer divise, etc.” Now this is one of those collocations of ideas which tends to create, or to strengthen, the erroneous impression I would dissipate. I do not for a moment suppose that M. Laugel intended to say that these ideas which he describes as ideas of the “Positive Philosophy,” are peculiarly the ideas of M. Comte. But little as he probably intended it, his expressions suggest this conception. In the minds of both disciples and antagonists, “the Positive Philosophy” means the philosophy of M. Comte; and to be imbued with the ideas of “the Positive Philosophy” means to be imbued with the ideas of M. Comte – to have received these ideas from M. Comte. After what has been said above, I need scarcely repeat that the conception thus inadvertently suggested, is a wrong one. M. Comte’s brief enunciations of these general truths, gave me no clearer apprehensions of them than I had before. Such clarifications of ideas on these ultimate questions, as I can trace to any particular teacher, I owe to Sir William Hamilton.

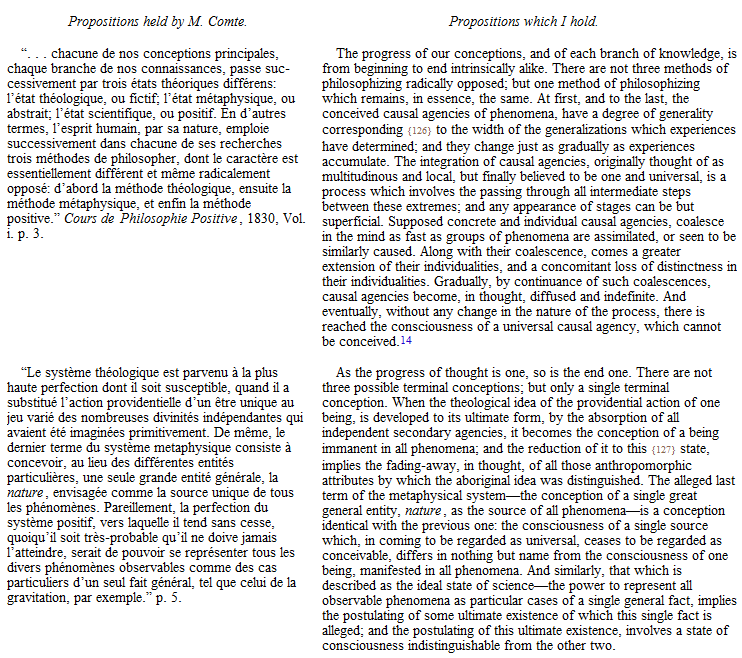

From the principles which M. Comte held in common with many preceding and contemporary thinkers, let us pass now to the principles that are distinctive of his system. Just as entirely as I agree with M. Comte on those cardinal doctrines which we jointly inherit; so entirely do I disagree with him on those cardinal doctrines which he propounds, and which determine the organization of his philosophy. The best way of showing this will be to compare, side by side, the —

14A clear illustration of this process, is furnished by the recent mental integration of Heat, Light, Electricity, etc., as modes of molecular motion. If we go a step back, we see that the modern conception of Electricity, resulted from the integration in consciousness, of the two forms of it involved in the galvanic battery and in the electric-machine. And going back to a still earlier stage, we see how the conception of statical electricity, arose by the coalescence in thought, of the previously-separate forces manifested in rubbed amber, in rubbed glass, and in lightning. With such illustrations before him, no one can, I think, doubt that the process has been the same from the beginning.

15Possibly it will be said that M. Comte himself admits that what he calls the perfection of the positive system, will probably never be reached; and that what he condemns is the inquiry into the natures of causes and not the general recognition of cause. To the first of these allegations I reply that, as I understand M. Comte, the obstacle to the perfect realization of the positive philosophy is the impossibility of carrying generalization so far as to reduce all particular facts to cases of one general fact – not the impossibility of excluding the consciousness of cause. And to the second allegation I reply that the essential principle of his philosophy is an avowed ignoring of cause altogether. For if it is not, what becomes of his alleged distinction between the perfection of the positive system and the perfection of the metaphysical system? And here let me point out that, by affirming exactly the opposite to that which M. Comte thus affirms, I am excluded from the positive school. If his own definition of positivism is to be taken, then, as I hold that what he defines as positivism is an absolute impossibility, it is clear that I cannot be what he calls a positivist.

16A friendly critic alleges that M. Comte is not fairly represented by this quotation, and that he is blamed by his biographer, M. Littré, for his too-great insistance on feeling as a motor of humanity. If in his “Positive Politics,” which I presume is here referred to, M. Comte abandons his original position, so much the better. But I am here dealing with what is known as “the Positive Philosophy;” and that the passage above quoted does not misrepresent it, is proved by the fact that this doctrine is re-asserted at the commencement of the Sociology.

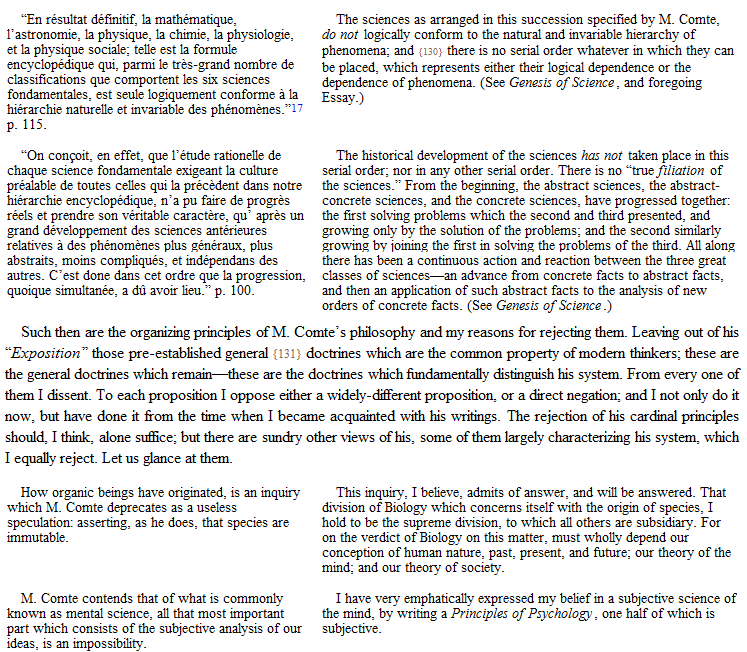

17In 1885, during a controversy with one of M. Comte’s English disciples, I was blamed for speaking “of Comte as making six sciences,” and was told that “in all Comte’s works, except the first, he makes seven sciences.” As I was dealing with The Positive Philosophy, I thought I could not do better than give the foregoing extract from the Cours de Philosophie Positive; and it did not occur to me that I was called upon to see whether, in any of his later voluminous works, M. Comte had made a different statement. My opponent, however, enlarged on this “blunder,” as he politely called it: apparently oblivious of the fact that if it was a blunder on my part to speak of Comte as recognizing six sciences when in his later days he recognized seven, it was a much more serious blunder on the part of Comte himself to have long overlooked the seventh.

Such then are the organizing principles of M. Comte’s philosophy and my reasons for rejecting them. Leaving out of his “ Exposition ” those pre-established general doctrines which are the common property of modern thinkers; these are the general doctrines which remain – these are the doctrines which fundamentally distinguish his system. From every one of them I dissent. To each proposition I oppose either a widely-different proposition, or a direct negation; and I not only do it now, but have done it from the time when I became acquainted with his writings. The rejection of his cardinal principles should, I think, alone suffice; but there are sundry other views of his, some of them largely characterizing his system, which I equally reject. Let us glance at them.

Here, then, are sundry other points, all of them important, and the last two supremely important, on which I am diametrically opposed to M. Comte; and did space permit, I could add many others. Radically differing from him as I thus do, in everything distinctive of his philosophy; and having invariably expressed my dissent, publicly and privately, from the time I became acquainted with his writings; it may be imagined that I have been not a little startled to find myself classed as one of the same school. That any who are acquainted with my writings, should suppose I have any general sympathy with M. Comte, save that implied by preferring proved facts to superstitions, astonishes me.

It is true that, disagreeing with M. Comte, though I do, in all those fundamental views that are peculiar to him, I agree with him in sundry minor views. The doctrine that the education of the individual should accord in mode and arrangement with the education of mankind, considered historically, I have cited from him; and have endeavoured to enforce it. I entirely concur in his opinion that there requires a new order of scientific men, whose function shall be that of co-ordinating the results arrived at by the rest. To him, I believe, I am indebted for the conception of a social consensus; and when the time comes for dealing with this conception, I shall state my indebtedness. And I also adopt his word, Sociology. There are, I believe, in the part of his writings which I have read, various incidental thoughts of great depth and value; and I doubt not that were I to read more of his writings, I should find others. 14 It is very probable, too, that I have said (as I am told I have) some things which M. Comte had already said. It would be difficult, I believe, to find two men who had no opinions in common. And it would be extremely strange if two men, starting from the same general doctrines established by modern science, should traverse some of the same fields of inquiry, without their lines of thought having any points of intersection. But none of these minor agreements can be of much weight in comparison with the fundamental disagreements above specified. Leaving out of view that general community which we both have with the scientific thought of the age, the differences between us are essential, while the correspondences are non-essential. And I venture to think that kinship must be determined by essentials, and not by non-essentials. 15

Joined with the ambiguous use of the phrase “Positive Philosophy,” which has led to a classing with M. Comte of many men who either ignore or reject his distinctive principles, there has been one special circumstance that has tended to originate and maintain this classing in my own case. The assumption of some relationship between M. Comte and myself, was unavoidably raised by the title of my first book – Social Statics. When that book was published, I was unaware that this title had been before used: had I known the fact, I should certainly have adopted an alternative title which I had in view. 16 If, however, instead of the title, the work itself be considered, its irrelation to the philosophy of M. Comte becomes abundantly manifest. There is decisive testimony on this point. In the North British Review for August, 1851, a reviewer of Social Statics says —