полная версия

полная версияThe History of the Indian Revolt and of the Expeditions to Persia, China and Japan 1856-7-8

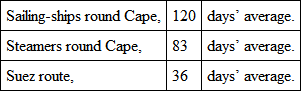

When the authorities at the War-office commenced their arrangements for despatching troops to India, they had to provide for a sea-voyage of about fourteen thousand miles. A question arose whether, without changing the route or shortening the distance, the duration of the voyage might not be lessened by the employment of steam-vessels instead of sailing-ships. The Admiralty, and most members of the government, opposed this change on various grounds, principally in relation to difficulties in the supply of fuel, but partly in relation to monsoons and other winds. By the 10th of July, out of 31 vessels chartered by the government and the Company for conveying troops to India, nearly all were sailing-ships. A change of feeling took place about that date; the nation estimated time to be so valuable, that the authorities were almost coerced into the chartering of some of the noble merchant-steamers, the rapid voyages of which were already known. Between the 10th of July and the 1st of December, 59 ships were chartered, of which 29 were screw-steamers. The autumnal averages of passages to India were greatly in favour of steamers. Within a certain number of weeks there were 62 troop-laden ships despatched from England to one or other of the ports, Calcutta, Madras, Bombay, Kurachee; the average duration of all the voyages was 120 days by sailing-vessels, and only 83 days by steamers – a diminution of nearly one-third. Extending the list of ships to a later date, so as to include a greater number, it was found that 82 ships carried 30,378 troops from the United Kingdom to India – thus divided: 66 sailing-ships carried 16,234 men, averaging 299 each; 27 steamers carried 14,144, averaging 522 each. It was calculated that 14,000 of these British soldiers arrived in India five weeks earlier, by the adoption of steam instead of sailing-vessels. It is impossible to estimate what amount of change might have been produced in the aspect of Indian affairs, had these steam-voyages been made in the summer rather than in the autumn; it might not have been permitted to the mutineers to rule triumphant at Lucknow till the spring of the following year, or the fidelity of wavering chieftains to give way under the long continuance of the struggle.

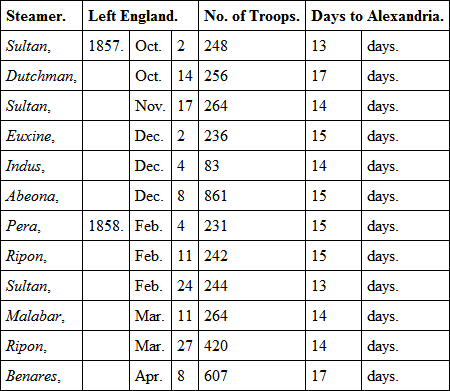

Besides the two inquiries concerning the promptness with which troops were sent, and the kind of vessels employed to convey them, there was a third relating to the route adopted. From the earliest news of the revolt at Meerut, many persons in and out of parliament strenuously recommended the use of the overland route, as being much shorter than any possible ocean-route. The Court of Directors viewed this proposal more favourably than the government. Until the month of September, ‘political difficulties’ were dimly hinted at by ministers, but without any candid explanations; and as the objections gave way in the month just named, the nation arrived at a pretty general conclusion that these difficulties had never been of a very insurmountable character. It is only fair to state, however, that many experienced men viewed the overland route with distrust, independently of any political considerations. They adverted to the incompleteness of the railway arrangements between Alexandria and Cairo; to the difficulty of troops marching or riding over the sandy desert from Cairo to Suez; to the wretchedness of Suez as a place of re-embarkation; and to the unhealthiness of a voyage down the Red Sea in hot summer weather. Nevertheless, it was an important fact that the East India directors, most of whom possessed personal knowledge concerning the routes to India, urged the government from the first to send at least a portion of the troops by the Suez route. It was not until the 19th of September that assent was given; and the 13th of October witnessed the arrival of the first detachment of English troops into the Indian Ocean viâ Suez. These started from Malta on the 1st of the month. On the 2d of October, the first regiment started from England direct, to take the overland route to India. The Peninsular and Oriental Steam-navigation Company, having practically almost a monopoly of the Suez route, conveyed the greater portion of the troops sent in this way; and it may be useful to note the length of journey in the principal instances. The following are tabulated examples giving certain items – such as, the name of the steamer, the date of leaving England, the number of troops conveyed, and the time of reaching Alexandria, to commence the overland portion of the journey:

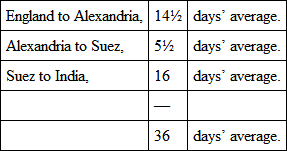

Thus the voyage was made on an average in about 14½ days, from the shores of England to those of Egypt. The landing at Alexandria, the railway journey to Cairo, the journey by vans and donkeys across the desert, the short detention at Suez, and the embarkation in another steamer at that port, occupied a number of days varying from 2 to 17 – depending chiefly on the circumstance whether or not a steamer was ready at Suez to receive the troops when they arrived from Alexandria; the average was about 5½ days. From Suez the voyages were made to Kurachee, Bombay, Ceylon, Madras, or Calcutta. The steamers took forward all the troops mentioned in the above list, as well as others which reached Alexandria by other means. Most of these troops were landed at Bombay or Kurachee, as being nearer than Calcutta; and the average length of voyage was just 16 days. The result, then, presented was this:

Those which went to Calcutta instead of Bombay or Kurachee, were about 3 days longer. Comparing these figures with those before given, we arrive at the following remarkable conclusion:

This, as a question of time, triumphantly justified all that had been said by the advocates of the shortest route; nor did it appear that there were any counterbalancing disadvantages experienced. Between the 6th of November 1857, and the 18th of May 1858, more than 5000 officers and soldiers landed in India, who had travelled by the Suez overland route from England.

CHAPTER XXX.

ROSE’S VICTORIES AT CALPEE AND GWALIOR

The fame of Sir Hugh Rose came somewhat unexpectedly upon the British people. Although well known to persons connected with India as a gallant officer belonging to the Bombay army, Rose’s military services were not ‘household words’ in the mother-country. Henry Havelock had made himself the hero of the wars of the mutiny by victories won in a time when the prospects were stern and gloomy; and it was not easy for others to become heroes of like kind, when compared in the popular mind with such a noble soldier. Hence it may possibly be that the relative merits of Campbell, Havelock, Neill, Wilson, Nicholson, Outram, Hope Grant, Inglis, Rose, Roberts, Napier, Eyre, Greathed, Jones, Smith, Lugard, and other officers, as military leaders, will remain undecided for a long period – until dispatches, memoirs, and journals have thrown light on the minuter details of the operations. Be this as it may, Sir Hugh Rose won for himself a high name by a series of military exploits skilfully conceived and brilliantly executed.

To understand the true scope of Rose’s proceedings in the months of May and June, it may be well to recapitulate briefly the state of matters at the close of the preceding month.

After Sir Hugh – with the 1st brigade of his Central India Field-force under Brigadier Stuart, and the 2d brigade under Brigadier Steuart – had captured the important city of Jhansi, in the early part of April, his subsequent proceedings were determined according to the manœuvres of the rebels elsewhere. Jhansi, as the strongest and most important place in Bundelcund, was a valuable conquest; but as the Ranee and Tanteea Topee – the one chieftainess of Jhansi, and the other a representative of the Mahratta influence of Nena Sahib in these parts – had escaped, with the greater part of their rebel troops, it became necessary to continue the attack against them wherever they might be. The safety of Jhansi, the succour of the sick and wounded, and the reconstruction of his field-force, detained Rose in that city until the 25th of the month; but Majors Orr and Gall were in the interim actively employed in chasing and defeating various bodies of rebels in the surrounding country. Orr was sent from Jhansi across the river Betwah to Mhow, to clear that region from insurgents, and then to join Rose on the way to Calpee; he captured a small fort at Goorwai, near the Betwah, and kept a sharp watch on the proceedings of the rebel Rajahs of Banpore and Shagurh. Gall, with two squadrons of the 14th Dragoons and three 9-pounders, was commissioned to reconnoitre the position and proceedings of the rebels on the Calpee road; he captured the fort of Lohare, belonging to the insurgent Rajah of Sumpter. Hearing that Tanteea Topee, Ram Rao Gobind, and other leaders, had made Calpee a stronghold, and intended to dispute the passage of the road from Jhansi to that place, Rose laid his plans accordingly. Calpee, though not a large place, was important as being on the right bank of the Jumna, and on the main road from Jhansi to Cawnpore. During the later days of April, Sir Hugh was on the road to Calpee with the greater part of his two brigades; the rest of his troops, under Orr, Gall, and one or two other officers, being engaged in detached services. At that same time, General Whitlock, after defeating many bodies of rebels in and near the Banda district, was gradually tending towards a junction with Rose at Calpee; while General Roberts was at Kotah, keeping a vigilant eye on numerous turbulent bands in Rajpootana.

When May arrived, Sir Hugh, needing the services of Majors Orr and Gall with his main force, requested General Whitlock to watch the districts in which those two officers had been engaged. Being joined on the 8th by his second brigade (except the regiments and detachments left to guard Jhansi), he resumed his march on the 9th. News reached him that Tanteea Topee and the Ranee intended to dispute his passage towards Calpee at a place called Koonch, with a considerable force of cavalry and infantry. As soon as he arrived at Koonch, he engaged the enemy, drove them from their intrenchment, entered the town, cut them up severely, pursued them to a considerable distance, and captured several guns. The heat on this occasion was fearful. Rose himself was three times during the day disabled by the sun, but on each occasion rallied, and was able to remount; he caused buckets of cold water to be dashed on him, and then resumed the saddle, all wet as he was. Thirteen of his gallant but overwrought soldiers were killed by sun-stroke. Nothing daunted by this severe ordeal, he marched on to Hurdwee, Corai, Ottah, and other villages obscure to English readers, capturing a few more guns as he went. Guided by the information which reached him concerning the proceedings of the rebels, Sir Hugh, when about ten miles from Calpee, bent his line of march slightly to the west, in order to strike the Jumna near Jaloun, a little to the northwest of Calpee. He had also arranged that Colonel Riddell, with a column from Etawah, should move down upon Calpee from the north; that Colonel Maxwell, with a column from Cawnpore, should advance from the east; and that General Whitlock should watch the country at the south. The purpose of this combination evidently was, not only that Calpee should be taken, but that all outlets for the escape of the rebels should as far as possible be closed.

On the 15th, the two brigades of Rose’s force joined at a point about six miles from Calpee. A large mass of the enemy here made a dash at the baggage and rear-guard, but were driven off without effecting much mischief. When he reached the Jumna, Rose determined to encamp for a while in a well-watered spot; and was enabled, by a personal visit from Colonel Maxwell, to concert further plans with him, to be put in force on the arrival of Maxwell’s column. On the 16th, a strong reconnoitring column under Major Gall proceeded along the Calpee road; it consisted of various detachments of infantry, cavalry, and horse-artillery. On the same day, the second brigade was attacked by the enemy in great force, and was not relieved without a sharp skirmish. On the 17th, the enemy made another attack, which was, however, repulsed with less difficulty. Nena Sahib’s nephew was believed to be the leader of the rebels on these two occasions. It was not until the 18th that Rose could begin shelling the earthworks which they had thrown up in front of the town. Greatly to their astonishment, the enemy found that Maxwell arrived at the opposite bank of the Jumna on the 19th, to assist in bombarding the place; they apparently had not expected this, and were not prepared with defences on that side. On the 20th, they came out in great force on the hills and nullahs around the town, attempted to turn the flank of Sir Hugh’s position, and displayed a determination and perseverance which they had not hitherto exhibited; but they were, as usual, driven in again. On the 21st, a portion of Maxwell’s column crossed the Jumna and joined Rose; while his heavy artillery and mortars were got into position. On the 22d, Maxwell’s batteries opened fire across the river, and continued it throughout the night, while Sir Hugh was making arrangements for the assault. The rebels, uneasy at the prospect before them, and needing nothing but artillery to reply to Maxwell’s fire, resolved to employ the rest of their force in a vigorous attack on Rose’s camp at Gulowlie. Accordingly, on that same day, the 22d, they issued forth from Calpee in great force, and attacked him with determination. Rose’s right being hard pressed by them, he brought up his reserve corps, charged with the bayonet, and repulsed the assailants at that point. Then moving his whole line forward, he put the enemy completely to rout. In these assaults, the rebels had the advantage of position; the country all round Calpee was very rugged and uneven, with steep ravines and numerous nullahs; insomuch that Rose had much difficulty in bringing his artillery into position. The assaults were made by numbers estimated at not far less than fifteen thousand men. The 71st and 86th foot wrought terrible destruction amongst the dense masses of the enemy. About noon on the 23d, the victorious Sir Hugh marched on from Gulowlie to Calpee. The enemy, who were reported to have chosen Calpee as a last stand-point, and to have sworn either to destroy Sir Hugh’s army or to die in the attempt, now forgot their oath; they fled panic-stricken after firing a few shot, and left him master of the town and fort of Calpee. This evacuation was hastened by the effect of Maxwell’s bombardment from the other side of the river.

Throughout the whole of the wars of the mutiny, the mutineers succeeded in escaping after defeat; they neither surrendered as prisoners of war, nor remained in the captured towns to be slaughtered. They were nimble and on the watch, knew the roads and jungles well, and had generally good intelligence of what was going on; while the British were seldom or never in such force as to be enabled completely to surround the places besieged: as a consequence, each siege ended in a flight. Thus it had been in Behar, Oude, the Doab, and Rohilcund; and thus Rose and his coadjutors found it in Bundelcund, Rajpootana, and Central India. Sir Hugh had given his troops a few hours’ repose after the hot work of the 22d; and this respite seems to have encouraged the rebels to flee from the beleaguered town; but they would probably have succeeded in doing the same thing, though with greater loss, if he had advanced at once. The British had lost about forty commissariat carts, laden with tea, sugar, arrack, and medical comforts; but their loss in killed and wounded throughout these operations was very inconsiderable.

Sir Hugh Rose inferred, from the evidences presented to his notice, that the rebels had considered Calpee an arsenal and a point of great importance. Fifteen guns were kept in the fort, of which one was an 18-pounder of the Gwalior Contingent, and two others 9-pounder mortars made by the rebels. Twenty-four standards were found, one of which had belonged to the Kotah Contingent, while most of the rest were the colours of the several regiments of the Gwalior Contingent. A subterranean magazine was found to contain ten thousand pounds of English powder in barrels, nine thousand pounds of shot and empty shells, a quantity of eight-inch filled shrapnell-shells, siege and ball ammunition, intrenching tools of all kinds, tents new and old, boxes of new flint and percussion muskets, and ordnance stores of all kinds – worth several lacs of rupees. There were also three or four cannon foundries in the town, with all the requisites for a wheel and gun-carriage manufactory. In short, it was an arsenal, which the rebels hoped and intended to hold to the last; but Sir Hugh’s victory at Gulowlie, and his appearance at Calpee, gave them a complete panic: they thought more of flight than of fighting.

The question speedily arose, however – Whither had the rebels gone? Their losses were very large, but the bulk of the force had unquestionably escaped. Some, it was found, had crossed the Jumna into the Doab, by a bridge of boats which had eluded the search of the British; but the rest, enough to form an army of no mean strength, finding that Rose had not fully guarded the side of Calpee leading to Gwalior, retreated by that road with amazing celerity. Sir Hugh thereupon organised a flying column to pursue them, under the command of Colonel Robertson. This column did not effect much, owing in part to the proverbial celerity of the rebels, and in part also to difficulties of other kinds. Heavy rains on the first two days rendered the roads almost impassable, greatly retarding the progress of the column. The enemy attempted to make a stand at Mahona and Indoorkee, two places on the road; but when they heard of the approach of Robertson, they continued their retreat in the direction of Gwalior. The column reached Irawan on the 29th; and there a brief halt was made until commissariat supplies could be sent up from Calpee. An officer belonging to the column adverted, in a private letter, to certain symptoms that the villagers were becoming tired of the anarchy into which their country had been thrown. ‘The feeling of the country is strong against the rebels now, whatever it may have been; and the rural population has welcomed our advent in the most unmistakable manner. At the different villages as we go along, many of them come out and meet us with earthen vessels full of water, knowing it to be our greatest want in such weather; and at our camping-ground they furnish us voluntarily with supplies of grain, grass, &c., in the most liberal manner. They declare the rebels plundered them right and left, and that they are delighted to have the English raj once more. It is not only the inhabitants of the towns and villages where we encamp who are so anxious to evince their good feeling; but the people, for miles round, have been coming to make their salaam, bringing forage for our camp with them, and thanking us for having delivered them from their oppressors. They say that for a year they have had no peace; but they have now a hope that order will be once more restored.’ Concerning this statement it may suffice to remark, that though the villagers were unquestionably in worse plight under the rebels than under the British, their obsequious protestations to that effect were not always to be depended on; their fears gave them duplicity, inducing them to curry favour with whichever side happened at the moment to be greatest in power.

Colonel Robertson, though he inflicted some loss on the fugitives, did not materially check them. His column – comprising the 25th Bombay native infantry, the 3d Bombay native cavalry, and 150 Hyderabad horse – pursued the rebels on the Gwalior road, but did not come up with the main body. On the 2d of June he was joined by two squadrons of the 14th dragoons, a wing of the 86th foot, and four 9-pounders. On the next day, when at Moharar, about midway between Calpee and Gwalior (fifty-five miles from each) he heard news of startling import from the last-named city – presently to be noticed. About the same time Brigadier Steuart marched to Attakona on the Gwalior road, with H.M. 71st, a wing of the 86th, a squadron of the 14th Dragoons, and some guns, to aid in the pursuit of the rebels.

While these events were in progress on the south of the Jumna, Colonel Riddell was advancing from the northwest on the north side of the same river. On the 16th of May, Riddell was at Graya, with the 3d Bengal Europeans, Alexander’s Horse, and two guns; he had a smart skirmish with a party of rebels, who received a very severe defeat. Some of the Etawah troops floated down the Jumna in boats, under the charge of Mr Hume, a magistrate, and safely joined Sir Hugh at Calpee. On their way they were attacked by a body of insurgents much more numerous than themselves; whereupon Lieutenant Sheriff landed with a hundred and fifty men at Bhijulpore, brought the rebels to an engagement, defeated them, drove them off, and captured four guns with a large store of ammunition. On the 25th, when on the banks of the Jumna some distance above Calpee, Colonel Riddell saw a camp of rebels on the other side, evidently resting a while after their escape on the 23d; he sent the 2d Bengal Europeans across, and captured much of the camp-equipage – the enemy not waiting to contest the matter with him.

When Calpee had been securely taken, and flying columns had gone off in pursuit of the enemy, to disperse if not to capture, Sir Hugh Rose conceived that the arduous labours of his Central India Field-force were for a time ended, and that his exhausted troops might take rest. He issued to them a glowing address, adverting with commendable pride to the unswerving gallantry which they had so long exhibited: ‘Soldiers! you have marched more than a thousand miles, and taken more than a hundred guns. You have forced your way through mountain-passes and intricate jungles, and over rivers. You have captured the strongest forts, and beaten the enemy, no matter what the odds, whenever you met him. You have restored extensive districts to the government, and peace and order now where before for a twelvemonth were tyranny and rebellion. You have done all this, and you never had a check. I thank you with all sincerity for your bravery, your devotion, and your discipline. When you first marched, I told you that you, as British soldiers, had more than enough of courage for the work which was before you, but that courage without discipline was of no avail; and I exhorted you to let discipline be your watchword. You have attended to my orders. In hardships, in temptations and danger, you have obeyed your general, and you have never left your ranks; you have fought against the strong, and you have protected the rights of the weak and defenceless, of foes as well as of friends. I have seen you in the ardour of the combat preserve and place children out of harm’s way. This is the discipline of Christian soldiers, and it is what has brought you triumphant from the shores of Western India to the waters of the Jumna, and establishes without doubt that you will find no place to equal the glory of your arms.’

Little did the gallant Sir Hugh suspect that the very day on which he issued this hearty and well-merited address (the 1st of June) would be marked by the capture of Gwalior by the defeated Calpee rebels, the flight of Scindia to Agra, and the necessity for an immediate resumption of active operations by his unrested Central India Field-force.

The rebels, it afterwards appeared, having out-marched Colonel Robertson, arrived on the 30th of May at the Moorar cantonment, in the neighbourhood of Gwalior, the old quarters of the Gwalior Contingent. Tanteea Topee, a leader whose activity was worthy of a better cause, had preceded them, to tamper with Scindia’s troops. The Maharajah, when he heard news of the rebels’ approach, sent an urgent message to Agra for aid; but before aid could reach him, matters had arrived at a crisis.

The position of the Maharajah of Gwalior had all along been a remarkable and perilous one, calling for the exercise of an amount of sagacity and prudence rarely exhibited by so youthful a prince. Although only twenty-three years of age, he had been for five years Maharajah in his own right, after shaking off a regency that had inflicted much misery on his country; and during these five years his conduct had won the respect of the British authorities. The mutiny placed him in an embarrassing position. The Gwalior Contingent, kept up by him in accordance with a treaty with the Company, consisted mainly of Hindustanis and Oudians, strongly in sympathy with their compatriots in the Jumna and Ganges regions. His own independent army, it is true, consisted chiefly of Mahrattas, a Hindoo race having little in common with the Hindustanis; but he could not feel certain how long either of the two armies would remain faithful. After many doubtful symptoms, in July 1857, as we have seen in former chapters, the Gwalior Contingent went over in a body to the enemy – thus adding ten or twelve thousand disciplined and well-armed troops to the rebel cause. Scindia contrived for two or three months to remain on neutral terms with the Contingent – on the one hand, not sanctioning their proceedings: on the other, not bringing down their enmity upon himself. During the winter they were engaged in encounters at various places, which have been duly noticed in the proper chapters. When Sir Hugh Rose’s name had become as much known and feared in Central India as Havelock’s had been in the Northwest Provinces many months before, the rebels began to look to Gwalior, the strongest city in that part of India, as a possible place of permanent refuge; and many of the Mahratta and Rajpoot chieftains appear to have come to an agreement, that if Scindia would not join them against the British, they would attack him, dethrone him, and set up another Maharajah in his stead. Meanwhile the Gwalior prince, a brave and shrewd man, as well as a faithful ally, looked narrowly at the circumstances that surrounded him. He had some cause to suspect his own national or regular army, but deemed it best to conceal his suspicions. There was every cause for apprehension, therefore, on his part, when he found a large body of insurgent troops approaching his capital – especially as some of the regiments of the old Gwalior Contingent were among the number.