полная версия

полная версияThe History of the Indian Revolt and of the Expeditions to Persia, China and Japan 1856-7-8

Gun-boats for India did not fail to find advocates. It was deemed almost a certainty that if light-draught vessels of this description had been on two or three of the Indian rivers, especially the Ganges and the Jumna, the mutineers would have met with formidable opponents; and even if the mutiny were quelled, a few gun-boats might act as a cheap substitute for a certain number of troops, in protecting places near the banks of the great rivers. Impressed with this conviction, the East India Company commissioned Messrs Rennie to build a small fleet of high-pressure iron gun-boats; each to have one boiler, two engines, two screw-propellers, and to carry a twelve-pounder gun amidships. The boats were seventy-five feet long by twelve wide, and were so constructed as to be stowed away in the hold of a ship for conveyance from England to India.

The means of locomotion or communication – railways, electric telegraphs, river-steamers, river gun-boats – formed only one portion of the schemes which occupied public thought during the first six months of the mutiny. Still more attention was paid to men – men for fighting in India and for defending our home-coasts. Shortly before the bad news began to arrive from India, a council order announced that the militia would not be called out in 1857; two months afterwards, in reply to a question in the House of Commons, Viscount Palmerston would not admit that circumstances were so serious as to necessitate a change in this arrangement; he thought that recruiting would be cheaper than the militia, as a means of keeping up the strength of the army. In August, however, the ministers obtained an act of parliament empowering them to embody some of the militia during the recess, if the state of public affairs should render such a step necessary. A system of active recruiting commenced, and was continued steadily during several months. These recruits were intended, not to increase the number of regiments, but to add a second battalion to many regiments, and to increase the number of men in each battalion; some of the regiments were, by this twofold process, raised from 800 or 1000 to 2000 or 2400 men each. Volunteers, also, came forward from France, Belgium, Germany, Italy, and other foreign countries; but these were mostly adventurers who sought officers’ commissions in India, and their services were not needed. The government made an attempt to encourage enlisting by offering commissions in the army to any private gentlemen who could bring forward a certain number of men each – a project not attended with much success. At certain crises, when the news from India was more than usually disastrous, appeals to patriotism shewed themselves in the newspapers – ‘A Young Englishman;’ ‘Another Young Englishman;’ ‘A True Briton;’ ‘One of the Middle Class;’ or ‘A Young Scotsman’ – would write to the journals, pour out his patriotism or his indignation, and shew what he would do if he only had the power. One proposed that clerks and shopmen out of situations should be embodied into a distinct volunteer corps; another said that, as he was a gentleman, and wished to avenge the foul murder of innocent women and children, he thought that he and such as he ought to be encouraged by commissions in the Indian army; another suggested that, if government would use them well, many young men would volunteer to serve in India, to return to their former mode of life when the mutiny was over. Some, rather in sarcasm than in earnest, suggested that drapers’ shopmen should drop the yard-measure, and go to India to fight; leaving to women the duty of serving muslins, and laces, and tapes. There was a certain meaning in all the suggestions, as expressive of honest indignation at the atrocities in India, especially those at Cawnpore; but, in its practical result, volunteering fell to the ground; and even the militia was not much appealed to. Various improvements were made in the condition of the common soldier; and recruits for the regular army came forward with much readiness.

We must now mention those who offered their monetary instead of their personal services in alleviation of the difficulties experienced in our Indian empire. Long before the mutinies in India had arrived at their greatest height, the question was anxiously debated both in that country and in England, what would be the worldly condition of the numerous families driven from their homes and robbed of all they possessed by the sepoys and marauders at the various stations? Every mail brought home fresh confirmation of the fact that the number of families thus impoverished was rapidly increasing; while on the other hand it was known that the East India Company could not reimburse the sufferers without much previous consideration. For, in the first place, it would have to be considered whether any distinction ought to be made between the two classes of Europeans in India – the civil and military servants of the Company, and those who, independent of the Company, had embarked capital in enterprises connected with indigo factories, opium farms, banks, printing-presses, &c.; and then would come a second inquiry whether the personal property only, or the commercial stock in trade also, should be considered as under the protection of the government. It was felt that immediate suffering ought not to wait for the solution of these questions; that when families had been burnt out or driven out of their homes, penniless and almost unclothed, immediate aid was needed from some quarter or other. This was admitted in the Punjaub, where Sir John Lawrence organised a fund for the relief of the necessitous; and it was admitted at Calcutta, where Lord and Lady Canning headed a subscription for providing shelter, raiment, and food to the hundreds of terrified fugitives who were constantly flocking to that capital. By the time the principal revolts of June were known in England, the last week of August had arrived; and then commenced one of those wonderful efforts in which London takes the lead of all the world – the collection of a large sum of money in a short time to ameliorate the sufferings arising out of some great calamity.

It was on the 25th of August that the lord-mayor presided at a meeting at the Mansion House to establish a fund for the relief of the sufferers by the Indian mutiny. The sum subscribed at the meeting did not much exceed a thousand pounds; but the whole merits of the case being set forth in newspapers, contributions poured in from all quarters, in the same noble spirit as had been manifested during the Crimean disasters. The high-born and the wealthy contributed large sums; the middle classes rendered their aid; country committees and town committees organised local subscriptions; large sums, made up of many small elements, were raised as collections after sermons in the churches and chapels; and when the Queen’s subjects in foreign and colonial regions heard of this movement, they sought to shew that they too shared in the common English feeling. Thousands swelled to tens of thousands, these to a hundred thousand, until in the course of a few months the fund rose to three or four hundred thousand pounds. In order to give system to the operations, thirty-five thousand circulars were issued, by the central committee in London, to all the authorities in church and state, to the ambassadors and ministers at foreign courts, to the governors of British colonies, and to the consuls at foreign ports.

This Mutiny Relief Fund was administered by four committees – General, Financial, Relief, and Ladies’ Committees. The General Committee settled the principles on which the fund was to be administered, determined the amount and destinations of the remittances to India, and controlled the proceedings of the subordinate committees. The Financial Committee supervised the accounts, the investments of the money, and the arrangement of remittances. The Relief Committee decided on applications for relief, on the administration of relief by donation or by loan, and on the application of means for the maintenance and education of children. The Ladies’ Committee took charge of such details as pertained more particularly to their own sex. Each of these committees met once a week. The first remittance was a sum of £2000 to Calcutta, to relieve some of the families who had been driven by the mutineers to seek shelter in that city. This was followed by frequent large remittances to the same place, and to Agra, Delhi, Lucknow, Bombay, and Lahore. Committees, formed in Calcutta and Bombay, corresponded with the head committee in London, and joined in carrying out plans for the expenditure of the fund. The donations and loans to persons who had arrived in England were small in amount; most of the aid being afforded to those who had not been able to leave India. The money was put out at interest as fast as the amount in hand exceeded the immediate requirements. At one time the government made an offer to appoint a royal commission for the administration of the fund; but this was declined; and there has been no reason for thinking that the transference of authority would have been beneficial. It was soon found that there were five classes of sufferers who would greatly need assistance from this fund – families of civil and military officers whose bungalows and furniture had been destroyed at the stations; the families of assistants, clerks, and other subordinate employés at the stations; European private traders and settlers, many of whom had been utterly impoverished; many missionary families and educational establishments; and the families of a large number of pensioners, overseers, artificers, indigo-workers, schoolmasters, shopkeepers, hotel-keepers, newspaper printers, &c. To apportion the amount of misery among these five classes would be impossible; but the past chapters of this work have afforded examples, sufficiently sad and numerous, of the mode in which all ranks of Europeans in India were suddenly plunged into want and desolation. At Agra, when the fort had been relieved from a long investment or siege by the rebels, almost the entire Christian population was not only houseless, but the majority were without the most essential articles of furniture or clothing; nearly all were living in cellars and vaults. At many other stations it was nearly as bad; at Lucknow it was still worse.

India speedily raised thirty thousand pounds on its own account, irrespective of aid from England; and most of this was expended at Calcutta in providing as follows: Board and lodging on arrival at Calcutta for refugees without homes or friends to receive them; clothing for refugees; monthly allowances for the support of families who were not boarded and lodged out of the fund; loans for purchasing furniture, clothing, &c.; free grants for similar purposes; passage and diet money on board Ganges steamers; loans to officers and others to pay for the passage of their families to England; free passage to England for the widows and families of officers; and education of the children of sufferers. These were nearly the same purposes as those to which the larger English fund was applied. The East India Company adopted a wholly distinct system in recognising the just claims of the officers more immediately in its service, and of the widows and children of those who fell during the mutiny – a system based on the established emoluments and pensions of all in the Company’s service.

It will thus be seen that the news of the Indian Revolt, when it reached London by successive mails, led to a remarkable and important series of suggestions and plans – intended either to strengthen the hands of the executive in dealing with the mutineers, or to succour those who had been plunged into want by the crimes of which those mutineers were the chief perpetrators.

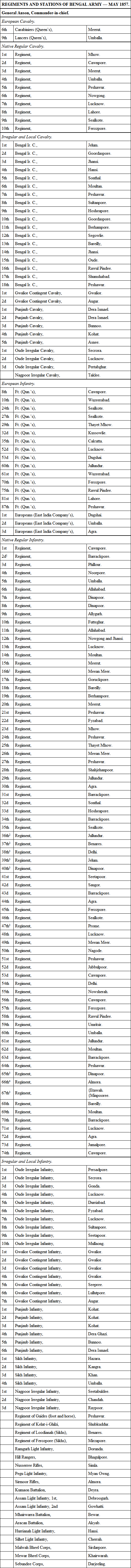

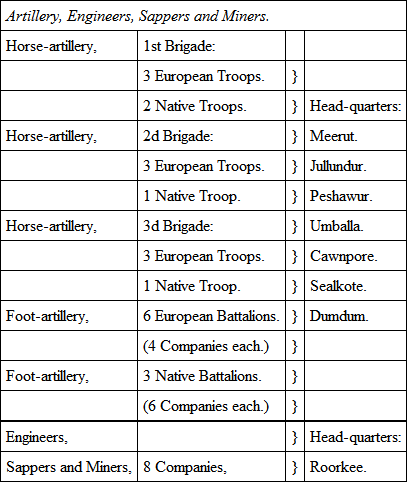

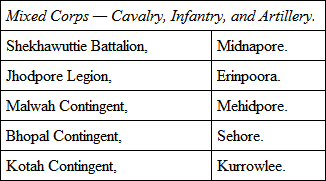

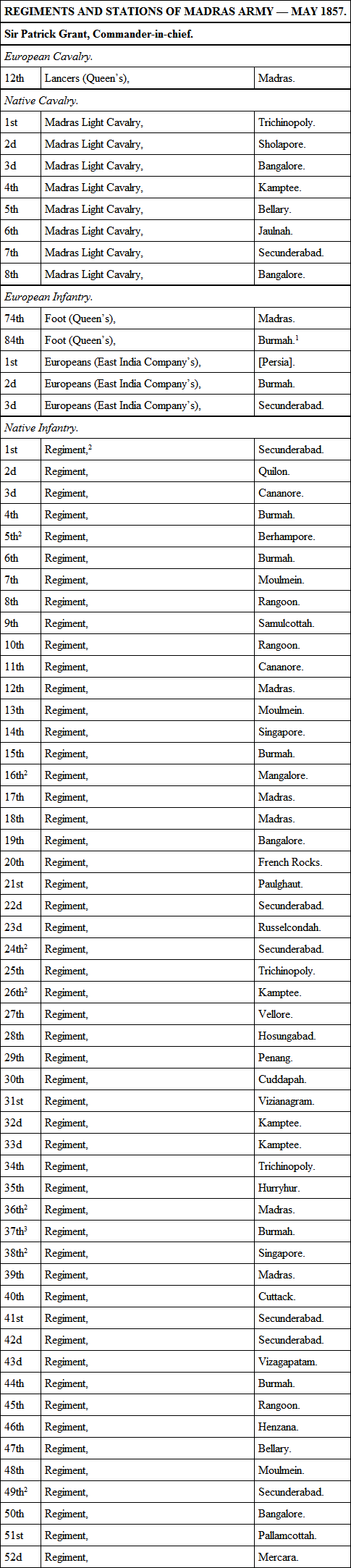

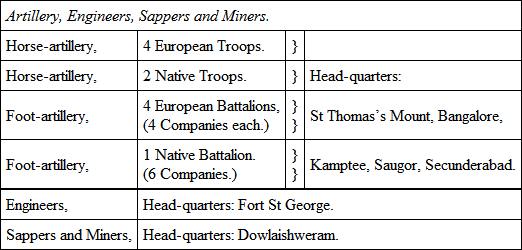

NoteAt the end of the last chapter a table was given of the number of troops, European and native, in all the military divisions of India, on the day when the mutiny commenced at Meerut. It will be convenient to present here a second tabulation on a wholly different basis – giving the designations of the regiments instead of the numbers of men, and naming the stations instead of the divisions in which they were cantoned or barracked. This will be useful for purposes of reference, in relation to the gradual annihilation of the Bengal Hindustani army. The former table applied to the 10th of May 1857; the present will apply to a date as near this as the East India Register will permit – namely, the 6th of May; while the royal troops in India will be named according to the Army List for the 1st of May – a sufficiently near approximation for the present purpose. A few possible sources of error may usefully be pointed out. 1. Some or other of the India regiments were at all times moving from station to station; and these movements may in a few cases render it doubtful whether a particular corps had or had not left a particular station on the day named. 2. The station named is that of the head-quarters and the bulk of the regiment: detachments may have been at other places. 3. The Persian and Chinese wars disturbed the distribution of troops belonging to the respective presidencies. 4. The disarming and disbanding at Barrackpore and Berhampore are not taken into account; for they were not known in London at the time of compiling the official list. 5. The Army List, giving an enumeration of royal regiments in India, did not always note correctly the actual stations at a particular time. These sources of error, however, will not be considerable in amount.

1Grenadiers.

2Volunteers.

3Volunteers.

4Goorkhas.

1Removed to Calcutta.

2Rifles.

3Grenadiers.

1Grenadiers.

2 Rifles.

1 The first troop of horse-artillery was called Leslie’s Troop.

CHAPTER XIV.

THE SIEGE OF DELHI: JUNE AND JULY

While these varied scenes were being presented; while sepoy regiments were revolting throughout the whole breadth of Northern India, and a handful of British troops was painfully toiling to control them; while Henry Lawrence was struggling, and struggling even to death, to maintain his position in Oude; while John Lawrence was sagaciously managing the half-wild Punjaub at a troublous time; while Wheeler at Cawnpore, and Colvin at Agra, were beset in the very thick of the mutineers; while Neill and Havelock were advancing up the Jumna; while Canning was doing his best at Calcutta, Harris and Elphinstone at Madras and Bombay, and the imperial government at home, to meet the trying difficulties with a determined front – while all this was doing, Delhi was the scene of a continuous series of operations. Every eye was turned towards that place. The British felt that there was no security for their power in India till Delhi was retaken; the insurgents knew that they had a rallying-point for all their disaffected countrymen, so long as the Mogul city was theirs; and hence bands of armed men were attracted thither by antagonistic motives. Although the real siege did not commence till many weary weeks had passed, the plan and preparations for it must be dated from the very day when the startling news spread over India that Delhi had been seized by rebellious sepoys, under the auspices of the decrepit, dethroned, debauched representative of the Moguls.

It was, as we have already seen (p. 70), on the morning of Monday the 11th of May, that the 11th and 20th regiments Bengal native infantry, and the 3d Bengal cavalry, arrived at Delhi after a night-march from Meerut, where they had mutinied on the preceding evening. At Delhi, we have also seen, those mutineers were joined by the 38th, 54th, and 74th native infantry. It was on that same 11th of May that evening saw the six mutinous regiments masters of the imperial city; and the English officers and residents, their wives and children, wanderers through jungles and over streams and rivers. What occurred within Delhi on the subsequent days is imperfectly known; the few Europeans who could not or did not escape were in hiding; and scanty notices only have ever come to light from those or other sources. A Lahore newspaper, three or four months afterwards, gave a narrative prepared by a native, who was within Delhi from the 21st of May to the 23d of June. Arriving ten days after the mutiny, he found the six regiments occupying the Selimgurh and Mohtabagh, but free to roam over the city; where the sepoys and sowars, aided by the rabble of the place, plundered the better houses and shops, stole horses from those who possessed them, ‘looted’ the passengers who crossed the Jumna by the bridge of boats, and fought with each other for the property which the fleeing British families had left behind them. After a few days, something like order was restored, by leaders who assumed command in the name of the King of Delhi. This was all the more necessary when new arrivals of insurgent troops took place, from Allygurh, Minpooree, Agra, Muttra, Hansi, Hissar, Umballa, Jullundur, Nuseerabad, and other places. The mutineers did not, at any time, afford proof that they were really well commanded; but still there was command, and the defence of the city was arranged on a definite plan. As at Sebastopol, so at Delhi; the longer the besiegers delayed their operations, the greater became the number of defenders within the place, and the stronger the defence-works.

It must be remembered, in tracing the history of the siege of Delhi, that every soldier necessary for forming the siege-army had to be brought from distant spots. The cantonment outside the city was wholly in the hands of the rebels; and not a British soldier remained in arms in or near the place. Mr Colvin at Agra speedily heard the news, but he had no troops to send for the recapture. General Hewett had a British force at Meerut – unskilfully handled, as many persons thought and still think; and it remained to be seen what arrangements the commander-in-chief could make to render this and other forces available for the reconquest of the important city.

Major-general Sir Henry Barnard was the medium of communication on this occasion. Being stationed at Umballa, in command of the Sirhind military division, he received telegraphic messages on the 11th of May from Meerut and Delhi, announcing the disasters at those places. He immediately despatched his aid-de-camp to Simla, to point out the urgent need for General Anson’s presence on the plains instead of among the hills. Anson, hearing this news on the 12th, first thought about his troops, and then about his own movements. Knowing well the extreme paucity of European regiments in the Delhi and Agra districts, and in all the region thence eastward to Calcutta, he saw that any available force to recover possession of Delhi must come chiefly from Sirhind and the Punjaub. Many regiments were at the time at the hill-stations of Simla, Dugshai, Kussowlie, Deyrah Dhoon, Subathoo, &c., where they were posted during a time of peace in a healthy temperate region; but now they had to descend from their sanitaria to take part in stern operations in the plains. The commander-in-chief sent instant orders to transfer the Queen’s 75th foot from Kussowlie to Umballa, the 1st and 2d Bengal Europeans from Dugshai to Umballa, the Sirmoor battalion from Deyrah Dhoon to Meerut, two companies of the Queen’s 8th foot from Jullundur to Phillour, and two companies of the Queen’s 81st foot, together with one company of European artillery, from Lahore to Umritsir. These orders given, General Anson himself left Simla on the evening of the 14th, and arrived at Umballa early on the 15th. Before he started, he issued the proclamation already adverted to, announcing to the troops of the native army generally that no cartridges would be brought into use against the conscientious wishes of the soldiery; and after he arrived at Umballa, fearing that his proclamation had not been strong enough, he issued another, to the effect that no new cartridges whatever should be served out – thereby, as he hoped, putting an end to all fear concerning objectionable lubricating substances being used; for he was not aware how largely hypocrisy was mixed up with sincerity in the native scruples on this point.

Anson and Barnard, when together at Umballa, had to measure well the forces available to them. The Umballa magazines were nearly empty of stores and ammunition; the artillery wagons were in the depôt at Phillour; the medical officers dreaded the heat for troops to move in such a season; and the commissariat was ill supplied with vehicles and beasts of burden and draught. The only effectual course was found to be, that of bringing small detachments from many different stations; and this system was in active progress during the week following Anson’s arrival at Umballa. On the 16th, troops came into that place from Phillour and Subathoo. On the 17th arrived three European regiments from the Hills,38 which were shortly to be strengthened by artillery from Phillour. The prospect was not altogether a cheering one, for two of the regiments at the station were Bengal native troops (the 5th and 60th), on whose fidelity only slight reliance could be placed at such a critical period. In order that no time might he lost in forming the nucleus of a force for Delhi, some of the troops were despatched that same night; comprising one wing of a European regiment, a few horse, and two guns. On successive days, other troops took their departure as rapidly as the necessary arrangements could be made; but Anson was greatly embarrassed by the distance between Umballa and the station where the siege-guns were parked; he knew that a besieging army would be of no use without those essential adjuncts; and it was on that account that he was unable to respond to Viscount Canning’s urgent request that he would push on rapidly towards Delhi.

On the 23d of May, Anson sketched a plan of operations, which he communicated to the brigadiers whose services were more immediately at his disposal. Leaving Sir Henry Barnard in command at Umballa, he proposed to head the siege-army himself. It was to consist39 of three brigades – one from Umballa, under Brigadier Halifax; a second from the same place, under Brigadier Jones; and a third from Meerut, under Brigadier Wilson. He proposed to send off the two brigades from Umballa on various days, so that all the corps should reach Kurnaul, fifty miles nearer to Delhi, by the 30th. Then, by starting on the 1st of June, he expected to reach Bhagput on the 5th, with all his Umballa force except the siege-train, which might possibly arrive on the 6th. Meanwhile Major-general Hewett was to organise a brigade at Meerut, and send it to Bhagput, where it would form a junction with the other two brigades. Ghazeeoodeen Nuggur being a somewhat important post, as a key to the Upper Doab, it was proposed that Brigadier Wilson should leave a small force there – consisting of a part of the Sirmoor battalion, a part of the Rampore horse, and a few guns – while he advanced with the rest of his brigade to Bhagput. Lastly, it was supposed that the Meerut brigade, by starting on the 1st or 2d of June, could reach the rendezvous on the 5th, and that then all could advance together towards Delhi. Such was General Anson’s plan – a plan that he was not destined to put in execution himself.

It will be convenient to trace the course of proceeding in the following mode – to describe the advance of the Meerut brigade to Bhagput, with its adventures on the way; then to notice in a similar way the march of the main body from Umballa to Bhagput; next the progress of the collected siege-army from the last-named town to the crest or ridge bounding Delhi on the north; and, lastly, the commencement of the siege-operations themselves – operations lamentably retarded by the want of a sufficient force of siege-guns.