полная версия

полная версияThe History of the Indian Revolt and of the Expeditions to Persia, China and Japan 1856-7-8

Sir John Lawrence was at first in some doubt what course to follow in relation to the liberty of the press. The Calcutta authorities, as we shall see in the next chapter, thought it proper to curtail that liberty in Bengal and the Northwest Provinces. Sir John, unwilling on the one hand to place the Europeans in the Punjaub in the tormenting condition of seclusion from all sources of news, and unwilling on the other to leave the news-readers at the mercy of inaccurate or unscrupulous news-writers at such a critical time, adopted a medium course. He caused the Lahore Chronicle to be made the medium of conveying official news of all that was occurring in India, so far as rapid outlines were concerned. The government secretary at that place sent every day to the editor of the newspaper an epitome of the most important public news. This epitome was printed on small quarter-sheets of paper, and despatched by each day’s post to all the stations in the Punjaub. The effect was – that false rumours and sinister reports were much less prevalent in the Punjaub than in Bengal; men were not thrown into mystery by a suppression of journalism; but were candidly told how events proceeded, so far as information had reached that remote part of India. The high character of the chief-commissioner was universally held as a guarantee that the news given in the epitome, whether little or much in quantity, would be honestly rendered; the scheme would have been a failure under a chief who did not command respect and win confidence. As the summer advanced, and dâks and wires were interrupted, the news obtainable became very scanty. The English in the Punjaub were placed in a most tantalising position. Aware that matters were going wrong at Delhi and Agra, at Lucknow and Cawnpore, they did not know how wrong; for communication was well-nigh cut off. As the cities just named lie between the Punjaub and Calcutta, all direct communication with the seat of government was still more completely cut off. The results of this were singularly trying. ‘Gradually,’ says an officer writing from the Punjaub, ‘papers and letters reached us from Calcutta viâ Bombay. It is not the least striking illustration of the complete revolution that has occurred in India, that the news from the Gangetic valley – say from Allahabad and Cawnpore – was known in London sooner than at Lahore. We had been accustomed to receive our daily letters and newspapers from every part of the empire with the same unfailing regularity as in England. Suddenly we found ourselves separated from Calcutta for two months of time. Painfully must a letter travel from the eastern capital to the western port – from Calcutta to Bombay; painfully must it toil up the unsettled provinces of the western coast; slowly must it jog along on mule-back across the sands of Sinde; many queer twists and unwonted turns must that letter take, many enemies must it baffle and elude, before, much bestamped, much stained with travel – for Indian letter-bags are not water-proof – it is delivered to its owner at Lahore… Slowly, very slowly, the real truth dragged its way up the country. It is only this very 29th of September that this writer in the Punjaub has read anything like a connected account of the fearful tragedy at Cawnpore, which, once read or heard, no Englishman can ever forget.’

Attention must now for a brief space be directed to the country of Sinde or Scinde; not so much for the purpose of narrating the progress of mutiny there, as to shew how it happened that there were few materials out of which mutiny could arise.

Sinde is the region which bounds the lower course of the river Indus, also called Sinde. The name is supposed to have had the same origin as Sindhi or Hindi, connected with the great Hindoo race. When the Indus has passed out of the Punjaub at its lower apex, it enters Sinde, through which it flows to the ocean, which bounds Sinde on the south; east is Rajpootana, and west Beloochistan. The area of Sinde is about equal to that of England without Wales. The coast is washed by the Indian Ocean for a distance of about a hundred and fifty miles; being, with very few exceptions, little other than a series of mud-banks deposited by the Indus, or low sand-hills blown in from the sea-beach. So low is most of the shore, that a wide expanse of country is overflowed at each high tide; it is a dreary swamp, scarcely observable from shipboard three or four miles out at sea. The mouths of the Indus are numerous, but so shallow that only one of them admits ships of any considerable burden; and even that one is subject to so many fluctuations in depth and in weather, that sea-going vessels scarcely enter it at all. Kurachee, the only port in Sinde, is a considerable distance west of all these mouths; and the mercantile world looks forward with much solicitude to the time when a railway will be formed from this port to Hydrabad, a city placed at the head of the delta of the Indus. This delta, in natural features, resembles that of the Nile rather than that of the Ganges, being nearly destitute of timber. On each side of the Indus, for a breadth varying from two to twelve miles, is a flat alluvial tract, in most places extremely fertile. Many parts of Sinde are little better than desert; such as the Pât, between Shikarpore and the Bolan Pass, and the Thur, nearer to the river. In general, it may be said that no part of Sinde is fertile except where the Indus irrigates it; for there is little either of rain or dew, and the climate is intensely hot. Camels are largely reared in Sinde; and the Sindians have abundant reason to value this animal. It is to him a beast of burden; its milk is a favourite article of diet; its hair is woven into coarse cloth; and it renders him service in many other ways.

The Sindians are an interesting race, both in themselves and in their political relations. They are a mixture of Jâts and Beloochees, among whom the distinction between Hindoo and Mussulman has a good deal broken down. The Beloochees are daring, warlike Mohammedans; the Jâts are Hindoos less rigorous in matters of faith and caste than those of Hindostan; while the Jâts who have become Mohammedans are a peaceful agricultural race, somewhat despised by both the others. The Sindians collectively are a dark, handsome, well-limbed race; and it was a favourite opinion of Sir William Jones, that they were the original of the gipsies. The languages spoken are a mixture of Hindi, Beloochee, and Persian.

The chain of events which brought Sinde under British rule may be traced in a few sentences. About thirteen centuries ago the country was invaded by the Persians, who ravaged it without making a permanent settlement. The califs at a later date conquered Sinde; from them it was taken by the Afghans of Ghiznee; and in the time of Baber it fell into the hands of the chief of Candahar. It was then, for a century and a half, a dependency of the Mogul Empire. For a few years Nadir Shah held it; next the Moguls retook it; and in 1756 Sinde fell under the rule of the Cabool khans, which was maintained nearly to the time when the British seized the sovereign power. Although subject to Cabool, Sinde was really governed by eight or ten native princes, called Ameers, who had among them three distinct territories marked by the cities of Hydrabad, Khyrpore, and Meerpoor. Under these ameers the government was a sort of military despotism, each ameer having a power of life and death; but in warlike affairs they were dependent on feudal chieftains, each of whom held an estate on condition of supplying a certain number of soldiers. The British had various trading treaties with the ameers; one of which, in 1832, opened the roads and rivers of Sinde to the commerce of the Company. When, in 1838, the eyes of the governor-general were directed anxiously towards Afghanistan, Sinde became involved in diplomatic conferences, in which the British, the Afghans, the Sindians, and Runjeet Singh were all concerned. These conferences led to quarrels, to treaties, to accusations of breach of faith, which we need not trace: suffice it to say that Sir Charles James Napier, with powers of the pen and of the sword intrusted to him, settled the Sinde difficulty once for all, in 1848, by fighting battles which led to the annexation of that country to the Company’s dominions. The former government was entirely put an end to; and the ameers were pensioned off with sums amounting in the aggregate to about fifty thousand pounds per annum. Some of these Ameers, like other princes of India, afterwards came to England in the hope of obtaining better terms from Queen Victoria than had been obtainable from the Company Bahadoor.

When Sinde became a British province, it was separated into three collectorates or districts – Shikarpore, Hydrabad, and Kurachee; a new system of revenue administration was introduced; annual fairs were established at Kurachee and Sukur; and peaceful commerce was everywhere so successfully established, that the country improved rapidly, greatly to the content of the mass of the people, who had formerly been ground down by the ameers’ government. For military purposes, Sinde was made a division, under the Bombay presidency.

Sinde, at the commencement of the mutiny, contained about seven thousand troops of all arms, native and European. The military arrangements had brought much distinction to Colonel (afterwards Brigadier-general) John Jacob, whose ‘Sinde Irregular Horse’ formed a corps much talked of in India. It consisted of about sixteen hundred men, in two regiments of eight hundred each, carefully drilled, and armed and equipped in the European manner, yet having only five European officers; the squadron and troop commanders were native officers. The brigadier uniformly contended that it was the best cavalry corps in India; and that the efficiency of such a regiment did not depend so much on the number of European officers, as on the manner in which they fulfilled their duties, and the kind of discipline which they maintained among the men. On these points he was frequently at issue with the Bengal officers; for he never failed to point out the superiority of the system in the Bombay army, where men were enlisted irrespective of caste, and where there were better means of rewarding individual merit.32 Nationally speaking, they were not Sindians at all; being drawn from other parts of India, in the ratio of three-fourths Mohammedans to one-fourth Hindoos.

When the mutiny began in the regions further east, ten or twelve permanent outposts on the Sinde frontier were held by detachments of the Sinde Irregular Horse, of forty to a hundred and twenty men each, wholly commanded by native officers. These men, and the head-quarters at Jacobabad (a camp named after the gallant brigadier), remained faithful, though sometimes tempted by sepoys and troopers of the Bengal army. A curious correspondence took place later in the year, through the medium of the newspapers, between Brigadier Jacob and Major Pelly on the one side, and Colonel Sykes on the other. The colonel had heard that Jacob ridiculed the greased cartridge affair, as a matter that would never be allowed to trouble his corps; and he sought to shew that it was no subject for laughter: ‘Brigadier John Jacob knows full well that if he were to order his Mohammedan soldiers (though they may venerate him) to bite a cartridge greased with pigs’ fat, or his high-caste troopers to bite a cartridge greased with cows’ fat, both the one and the other would promptly refuse obedience, and in case he endeavoured to enforce it, they would shoot him down.’ Jacob and Pelly at once disputed this; they both asserted that the Mohammedans and Hindoos in the Sinde Horse would never be mutinous on such a point, unless other sources of dissatisfaction existed, and unless they believed it was purposely done to insult their faith. ‘If it were really necessary,’ said the brigadier, ‘in the performance of our ordinary military duty, to use swine’s fat or cows’ fat, or anything else whatever, not a word or a thought would pass about the matter among any members of the Horse, and the nature of the substances made use of would not be thought of or discussed at all, except with reference to the fitness for the purpose to which they were to be applied.’ The controversialists did not succeed in convincing each other; they continued to hold diametrically opposite opinions on a question intimately connected with the early stages of the mutiny – thereby adding to the perplexities of those wishing to solve the important problem: ‘What was the cause of the mutiny?’

Owing partly to the great distance from the disturbed provinces of Hindostan, partly to the vicinity of the well-disposed Bombay army, and partly to the activity and good organisation of Jacob’s Irregular Horse, Sinde was affected with few insurgent proceedings during the year. At one time a body of fanatical Mohammedans would unfurl the green flag, and call upon each other to fight for the Prophet. At another time, gangs of robbers and hill-men, of which India has in all ages had an abundant supply, would take advantage of the troubled state of public feeling to rush forth on marauding expeditions, caring much for plunder and little for faith of any kind. At another, alarms would be given which induced European ladies and families to take refuge in the forts or other defensive positions at Kurachee, Hydrabad, Shikarpore, Jacobabad, &c., where English officers were stationed. At another, regiments of the Bengal army would try to tamper with the fidelity of other troops in Sinde. But of these varied incidents, few were so serious in results as to need record here. One, interesting in many particulars, arose out of the following circumstance: When some of the Sinde forces were sent to Persia, the 6th Bengal irregular cavalry arrived to supply their place. These troopers, when the mutiny was at least four months old, endeavoured to form a plan with some Beloochee Mohammedans for the murder of the British officers at the camp of Jacobabad. A particular hour on the 21st of August was named for this outrage, in which various bands of Beloochees were invited to assist. The plot was revealed to Captain Merewether, who immediately confided in the two senior native officers of the Sinde Irregular Horse. Orders were issued that the day’s proceedings should be as usual, but that the men should hold themselves in readiness. Many of the border chiefs afterwards sent notice to Merewether of what had been planned, announcing their own disapproval of the conspiracy. At a given hour, the leading conspirator was seized, and correspondence found upon him tending to shew that the Bengal regiment having failed in other attempts to seduce the Sinde troops from their allegiance, had determined to murder the European officers as the chief obstacles to their scheme. The authorities at Jacobabad wished Sir John Lawrence to take this Bengal regiment off their hands; but the experienced chief in the Punjaub would not have the dangerous present; he thought it less likely to mutiny where it was than in a region nearer to Delhi.

The troops in the province of Sinde about the middle of August were nearly as follows: At Kurachee – the 14th and 21st Bombay native infantry; the 2d European infantry; the depôt of the 1st Bombay Fusiliers; and the 3d troop of horse artillery. At Hydrabad – the 13th Bombay native infantry; and a company of the 4th battalion of artillery. At Jacobabad – the 2d Sinde irregular horse; and the 6th Bengal irregular cavalry. At Shikarpore and Sukur, the 16th Bombay native infantry; and a company of the 4th battalion of artillery. The whole comprised about five thousand native troops, and twelve hundred Europeans.

At a later period, when thanks were awarded by parliament to those who had rendered good service in India, the name of Mr Frere, commissioner for Sinde, was mentioned, as one who ‘has reconciled the people of that province to British rule, and by his prudence and wisdom confirmed the conquest which had been achieved by the gallant Napier. He was thereby enabled to furnish aid wherever it was needed, at the same time constantly maintaining the peace and order of the province.’

NotesThis will be a suitable place in which to introduce two tabular statements concerning the military condition of India at the commencement of the mutiny. All the occurrences narrated hitherto are those in which the authorities at Calcutta were compelled to encounter difficulties without any reinforcements from England, the time elapsed having been too short for the arrival of such reinforcements.

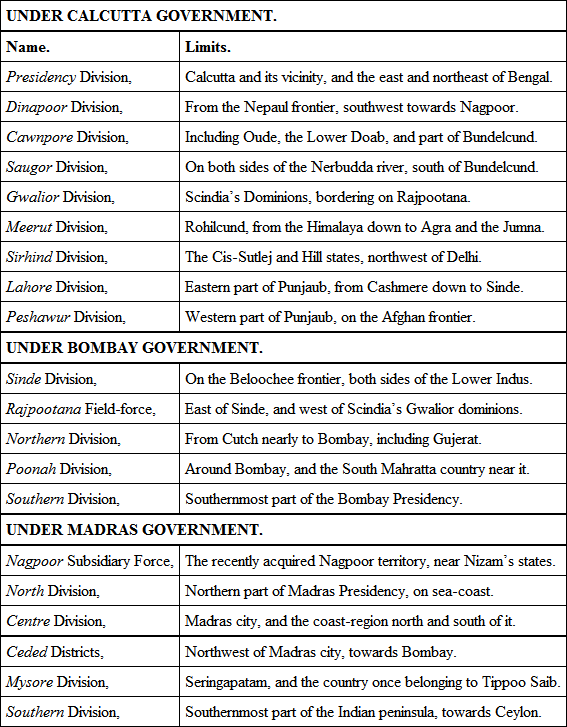

Military Divisions of India.– At the period of the outbreak, and for some time afterwards, India was marked out for military purposes into divisions, each under the command of a general, brigadier, or other officer, responsible for all the troops, European and native, within his division. The names and localities of these divisions are here given; on the authority of a military map of India, engraved at the Topographical Depôt under the direction of Captain Elphinstone of the Royal Engineers, and published by the War Department. Each division was regarded as belonging to, or under the control of, one of the three presidencies. We shall therefore group them under the names of the three presidential cities, and shall append a few words to denote locality:

It may be useful to remark that these military divisions are not necessarily identical in area or boundaries with the political provinces or collectorates, the two kinds of territorial limits being based on different considerations.

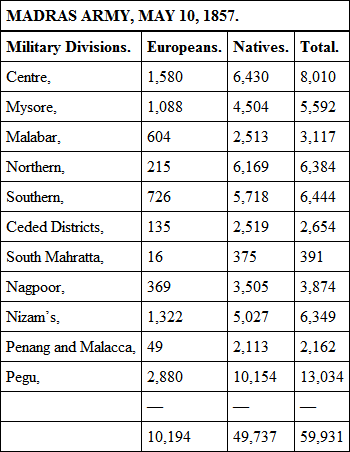

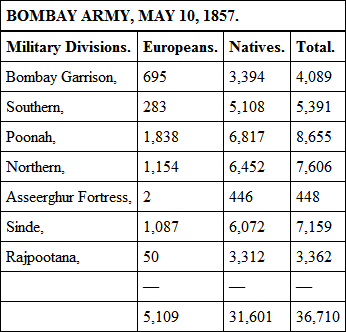

Armies of India, at the Commencement of the Mutiny.– During the progress of the military operations, it was frequently wished in England that materials were afforded for shewing the exact number of troops in India when the troubles began. The Company, to respond to this wish, caused an elaborate return to be prepared, from which a few entries are here selected. The names and limits of the military divisions correspond nearly, but not exactly, to those in the above list.

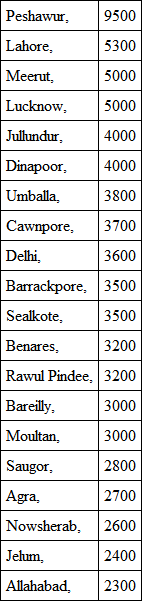

The Europeans in this list include all grades of officers as well as rank and file; and among the officers are included those connected with the native regiments. The natives, in like manner, include all grades, from subadars down to sepoys and sowars. The Punjaub, it will be seen, alone contained 40,000 troops. The troops were stationed at 160 cantonments, garrisons, or other places. As shewing gradations of rank, the Europeans comprised 2271 commissioned officers, 1602 non-commissioned officers, and 18,815 rank and file; the natives comprised 2325 commissioned officers, 5821 non-commissioned officers, and 110,517 rank and file. The stations which contained the largest numbers were the following:

These 20 principal stations thus averaged 3800 troops each, or nearly 80,000 altogether.

This list was more fully made out than that for the Bengal army; since it gave the numbers separately of the dragoons, light cavalry, horse-artillery, foot-artillery, sappers and miners, European infantry, native infantry, and veterans. The ratio of Europeans to native troops was rather higher in the Madras army (about 20 per cent.) than in that of Bengal (19 per cent.) More fully made out in some particulars, it was less instructive in others; the Madras list pointed out the location of all the detachments of each regiment, whereas the Bengal list gave the actual numbers at each station, without mentioning the particular regiments of which they were composed. Hence the materials for comparison are not such as they might have been had the lists been prepared on one uniform plan. There were about 36 stations for these troops, but the places which they occupied in small detachments raised the total to a much higher number. Although Pegu is considered to belong to the Bengal presidency, it was mostly served by Madras troops. Besides the forces above enumerated, there were nearly 2000 Madras troops out of India altogether, on service in Persia and China.

The Bombay army was so dislocated at that period, by the departure of nearly 14,000 troops to Persia and Aden, that the value of this table for purposes of comparison becomes much lessened. Nevertheless, it affords means of knowing how many troops were actually in India at the time when their services were most needed. On the other hand, about 5000 of the troops in the Bombay presidency belonged to the Bengal and Madras armies. The different kinds of troops were classified as in the Madras army. The regular military stations where troops took up their head-quarters, were about 20 in number; but the small stations where mere detachments were placed nearly trebled this number. The Europeans were to the native troops only as 16 to 100.

As a summary, then, we find that India contained, on the day when the mutinies began, troops to the number of 238,002 in the service of the Company, of whom 38,001 were Europeans, and 200,001 natives – 19 Europeans to 100 natives. An opportunity will occur in a future page for enumerating the regiments of which these three armies were composed.

CHAPTER XIII.

PREPARATIONS: CALCUTTA AND LONDON

Before entering on a narrative of the great military operations connected with the siege of Delhi, and with Havelock’s brilliant advance from Allahabad to Cawnpore and Lucknow, it will be necessary to glance rapidly at the means adopted by the authorities to meet the difficulties arising out of the mutiny – by the Indian government at Calcutta, and by the imperial government in London. For, it must be remembered that – however meritorious and indispensable may have been the services of those who arrived in later months – the crisis had passed before a single additional regiment from England reached the scene of action. There was, as we have seen in the note appended to the preceding chapter, a certain definite amount of European military force in India when the mutiny began; there were also certain regiments of the Queen’s army known to be at different spots in the region lying between the Cape of Good Hope on the west and Singapore on the east; and it depended on the mode of managing those materials whether India should or should not be lost to the English. There will therefore be an advantage in tracing the manner in which the Calcutta government brought into use the resources immediately or proximately available; and the plans adopted by the home government to increase those resources.

It is not intended in this place to discuss the numerous questions which have arisen in connection with the moral and political condition of the natives of India, or the relative fitness of different forms of government for the development of their welfare. Certain matters only will be treated, which immediately affected the proceedings of those intrusted with this grave responsibility at so perilous a time. Three such at once present themselves for notice, in relation to the Calcutta government – namely, the military measures taken to confront the mutineers; the judicial treatment meted out to them when conquered or captured; and the precautions taken in reference to freedom of public discussion on subjects likely to foster discontent.

First, in relation to military matters. England, by a singular coincidence, was engaged in two Asiatic wars at the time when the Meerut outbreak marked the commencement of a formidable mutiny. Or, more strictly, one army was returning after the close of a war with Persia; while another was going out to begin a war with China. It will ever remain a problem of deep significance what would have become of our Indian empire had not those warlike armaments, small as they were, been on the Indian seas at the time. The responsible servants of the Company in India did not fail to recognise the importance of this problem – as will be seen from a brief notice of the plans laid during the earlier weeks of the mutiny.