полная версия

полная версияThe History of the Indian Revolt and of the Expeditions to Persia, China and Japan 1856-7-8

The inmates of the fort naturally suffered an agony of suspense on the night of the 6th. When they heard the bugle, and the subsequent firing, they believed the mutineers had arrived from Benares; and as the intensity of the sound varied from time to time, so did they picture in imagination the varying fortunes of the two hypothetical opposing forces – the supposed insurgents from the east, and the supposed loyal 6th regiment. Soon were they startled by a revelation of the real truth – that the firing came from their own trusted sepoys. The Europeans in the fort, recovering from their wonder and dismay, were fortunately enabled to disarm the eighty sepoys at the gate through the energy of Lieutenant Brasyer; and it was then found that these fellows had loaded and capped their muskets, ready to turn out. Five officers succeeded in entering during the night, three of them naked, having had to swim the Ganges. For twelve days did the Europeans remain within the fort, not daring to emerge for many hours at a time, lest the four hundred Sikhs should prove faithless in the hour of greatest need. The chief streets of the city are about half a mile from the fort; and during several days and nights troops of rioters were to be seen rushing from place to place, plundering and burning. Day and night the civilians manned the ramparts, succeeding each other in regular watches – now nearly struck down by the hot blazing sun; now pouring forth shot and shell upon such of the insurgents as were within reach. The civilians or volunteers formed themselves into three corps; one of which, called the Flagstaff Division, was joined by about twenty railway men – sturdy fellows who had suffered like the rest, and were not slow to avenge themselves on the mutineers whenever opportunity offered. After a time, the volunteers sallied forth into the city with the Sikhs, and had several skirmishes in the streets with the insurgents – delighted at the privilege of quitting for a few hours the hot crowded fort, even to fight. It was by degrees ascertained that conspiracy had been going on in the city before the actual outbreak occurred. The standard of insurrection was unfurled by a native unknown to the Europeans: some supposed him to be a moulvie, or Mohammedan religious teacher; but whatever may have been his former position, he now announced himself as viceroy of the King of Delhi. He quickly collected about him three or four thousand rebels, sepoys and others, and displayed the green flag that constitutes the Moslem symbol. The head-quarters of this self-appointed chieftain were in the higher part of the city, at the old Mohammedan gardens of Sultan Khoosroo; there the prisoners taken by the mutineers were confined – among whom were the native Christian teachers belonging to the Rev. Mr Hay’s mission.

The movements of Colonel Neill must now be traced. No sooner did this gallant and energetic officer hear of the occurrences at Allahabad, than he proceeded to effect at that place what he had already done at Benares – re-establish English authority by a prompt, firm, and stern course of action. The distance between the two cities being about seventy-five miles, he quickly made the necessary travelling arrangements. He left Benares on the evening of the 9th, accompanied by one officer and forty-three men of the Madras Fusiliers. The horses being nearly all taken off the road, he found much difficulty in bringing in the dâk-carriages containing the men; but this and all other obstacles he surmounted. He found the country between Mirzapore and Allahabad infested with bands of plunderers, the villages deserted, and none of the authorities remaining. Major Stephenson, with a hundred more men, set out from Benares on the same evening as Neill; but his bullock-vans were still more slow in progress; and his men suffered much from exposure to heat during the journey. Neill reached Allahabad on the afternoon of the 11th. He found the fort almost completely invested; the bridge of boats over the Ganges in the hands of a mob, and partly broken; and the neighbouring villages swarming with insurgents. By cautious manœuvring at the end of the Benares road, he succeeded in obtaining boats which conveyed him and his handful of men over to the fort. He at once assumed command, and arranged that on the following morning the enemy should be driven out of the villages, and the bridge of boats recaptured. Accordingly, on the morning of the 12th he opened fire with several round-shot, and then attacked the rebels in the village of Deeragunge with a detachment of Fusiliers and Sikhs: this was effectively accomplished, and a safe road opened for the approach of Major Stephenson’s detachment on the evening of that day. On the 13th the insurgents were driven out of the village of Kydgunge. Neill had now a strange enemy to combat within the fort itself – drunkenness and relaxed discipline. The Sikhs, during their sallies into the city before his arrival, had gained entrance into some of the deserted warehouses of wine-merchants and others in the town, had brought away large quantities of beverage, and had sold these to the European soldiers within the fort – at four annas (sixpence) per bottle for wine, spirits, or beer indiscriminately; drunkenness and disorganisation followed, requiring determined measures on the part of the commandant. He bought all the remaining liquors obtainable, for commissariat use; and kept a watchful eye on the stores still remaining in the warehouses in the town. Neill saw reason for distrusting the Sikhs; they had remained faithful up to that time, but nevertheless exhibited symptoms which required attention. As soon as possible, he got them out of the fort altogether, and placed them at various posts in the city where they might still render service if they chose to remain faithful. His opinion of the native troops was sufficiently expressed in this passage in one of his dispatches: ‘I felt that Allahabad was really safe when every native soldier and sentry was out of the fort; and as long as I command I shall not allow one to be on duty in it.’ Nothing can be more striking than the difference of views held by Indian officers on this point; some distrusted the natives from the first, while others maintained faith in them to a very disastrous extent.

From the time when Neill obtained the upper-hand in Allahabad, he was incessantly engaged in chastising the insurgents in the neighbourhood. He sent a steamer up the Jumna on the 15th, with a howitzer under Captain Harward, and twenty fusiliers under Lieutenant Arnold; and these worked much execution among the rebels on the banks. A combined body of fusiliers, Sikhs, and irregular cavalry made an attack on the villages of Kydgunge and Mootingunge, on the banks of the Jumna, driving out the insurgents harboured there, and mowing them down in considerable numbers. On subsequent days, wherever Neill heard of the presence of insurgents in any of the surrounding villages, he at once attacked them; and great terror seized the hearts of the malcontents in the city at the celerity with which guns and gibbets were set to work. On the 18th he sent eighty fusiliers and a hundred Sikhs up the river in a steamer, to destroy the Patan village of Durriabad, and the Meewattie villages of Sydabad and Russelpore. It was not merely in the villages that these active operations were necessary; a large number of the mutinous sepoys went off towards Delhi on the day after the outbreak, leaving the self-elected chief to manage his rabble-army as he liked; and it was against this rabble that many of the expeditions were planned. The city suffered terribly from this double infliction; for after the spoliation and burning effected by the marauders, the English employed cannon-balls and musketry to drive those marauders out of the streets and houses; and Allahabad thus became little other than a mass of blackened ruins. Colonel Neill organised a body of irregular cavalry by joining Captain Palliser’s detachment of the 13th irregulars with the few men of Captain Alexander’s corps still remaining true to their salt. A force of about a hundred and sixty Madras Fusiliers started from Benares on the 13th, under Captain Fraser; he was joined on the road by Captain Palliser’s detachment of troopers, just adverted to, of about eighty men, and the two officers then proceeded towards Allahabad. They found the road almost wholly in the hands of rebels and plunderers; but by fighting, hanging, and burning, they cleared a path for themselves, struck terror into the evildoers, and recovered much of the Company’s treasure that had fallen into hostile hands. It is sad to read of six villages being reduced to ashes during this one march; but stringent measures were absolutely necessary to a restoration of order and obedience. Fraser and Palliser reached Allahabad on the 18th, and their arrival enabled Neill to prosecute two objects which he had at heart – the securing of Allahabad, and the gradual collection of a force that might march to the relief of poor Sir Hugh Wheeler and the other beleaguered Europeans at Cawnpore. During these varied operations, the officers and men were often exposed during the daytime to a heat so tremendous that nothing but an intense interest in their work could have kept them up. ‘If I can keep from fever,’ wrote one of them, ‘I shan’t care; for excitement enables one to stand the sun and fatigue wonderfully. At any other time the sun would have knocked us down like dogs; but all this month we have been out in the middle of the day, toiling like coolies, yet I have never been better in my life – such an appetite!’ To meet temporary exigencies, the church, the government offices, the barracks, the bungalows – all were placed at the disposal of the English troops, as fast as they arrived up from Calcutta. These reinforcements, during the second half of the month, consisted chiefly of detachments of her Majesty’s 64th, 78th, and 84th foot. The peaceful inhabitants began to return to the half-ruined city, shattered houses were hastily rebuilt or repaired, trade gradually revived, bullocks and carriages arrived in considerable number, supplies were laid in, the weather became cooler, the cholera abated, and Colonel Neill found himself enabled to look forward with much confidence to the future. The fort, during almost the whole of the month, had been very much crowded, insomuch that the inmates suffered greatly from heat and cholera. Two steam-boat loads of women and children were therefore sent down the river towards Calcutta; and all the non-combatants left the fort, to reoccupy such of their residences as had escaped demolition. Some of the European soldiers were tented on the glacis; others took up quarters in a tope of trees near the dâk-bungalow; lastly, a hospital was fitted up for the cholera patients.

With the end of June came tranquillity both to Benares and to Allahabad, chiefly through the determined measures adopted by Colonel Neill; and then he planned an expedition, the best in his power, for Cawnpore – the fortunes of which will come under our notice in due time.

NotesThe Oude Royal Family.– When the news reached England that the deposed King of Oude had been arrested at Calcutta, in the way described in the present chapter, on suspicion of complicity with the mutineers, his relations, who had proceeded to London to appeal against the annexation of Oude by the Company, prepared a petition filled with protestations of innocence, on his part and on their own. The petition was presented to the House of Lords by Lord Campbell, though not formally received owing to some defect in phraseology. A memorial to Queen Victoria was couched in similar form. The petition and memorial ran as follows:

‘The petition of the undersigned Jenabi Auliah Tajara Begum, the Queen-mother of Oude; Mirza Mohummud Hamid Allie, eldest son and heir-apparent of his Majesty the King of Oude; and Mirra Mohummud Jowaad Allie Sekunder Hushmut Bahadoor, next brother of his Majesty the King of Oude, sheweth:

‘That your petitioners have heard with sincere regret the tidings which have reached the British kingdom of disaffection prevailing among the native troops in India; and that they desire, at the earliest opportunity, to give public expression to that solemn assurance which they some time since conveyed to her Majesty’s government, that the fidelity and attachment to Great Britain which has ever characterised the royal family of Oude continues unchanged and unaffected by these deplorable events, and that they remain, as Lord Dalhousie, the late governor-general of India, emphatically declared them, “a royal race, ever faithful and true to their friendship with the British nation.”

‘That in the midst of this great public calamity, your petitioners have sustained their own peculiar cause of pain and sorrow in the intelligence which has reached them, through the public papers, that his Majesty the King of Oude has been subjected to restraint at Calcutta, and deprived of the means of communicating even with your petitioners, his mother, son, and brother.

‘That your petitioners desire unequivocally and solemnly to assure her Majesty and your lordships, that if his Majesty the King of Oude has been suspected of any complicity in the recent disastrous occurrences, such suspicion is not only wholly and absolutely unfounded, but is directed against one, the whole tenor of whose life, character, and conduct directly negatives all such imputations. Your petitioners recall to the recollection of your lordships the facts relating to the dethronement of the King of Oude, as set forth in the petition presented to the House of Commons by Sir Fitzroy Kelly on the 25th of May last, that when resistance might have been made, and was even anticipated by the British general, the King of Oude directed his guards and troops to lay aside their arms, and that when it was announced to him that the territories of Oude were to be vested for ever in the Honourable East India Company, the king, instead of offering resistance to the British government, after giving vent to his feelings in a burst of grief, descended from his throne, declaring his determination to seek for justice at her Majesty’s throne, and from the parliament of England.

‘That since their resort to this country, in obedience to his Majesty’s commands, your petitioners have received communications from his Majesty which set forth the hopes and aspirations of his heart; that those communications not only negative all supposition of his Majesty’s personal complicity in any intrigues, but fill the minds of your petitioners with the profound conviction that his Majesty would feel, with your petitioners, the greatest grief and pain at the events which have occurred. And your petitioners desire to declare to your lordships, and to assure the British nation, that although suffering, in common with his heart-broken family, from the wrongs inflicted on them, from the humiliations of a state of exile, and their loss of home, authority, and country, the King of Oude relies only on the justice of his cause, appeals only to her Majesty’s throne and to the parliament of Great Britain, and disdains to use the arm of the rebel and the traitor to maintain the right he seeks to vindicate.

‘Your petitioners therefore pray of your lordships that, in the exercise of your authority, you will cause justice to be done to his Majesty the King of Oude, and that it may be forthwith explicitly made known to his Majesty and to your petitioners wherewith he is charged, and by whom, and on what authority, so that the King of Oude may have full opportunity of refuting and disproving the unjust suspicions and calumnies of which he is now the helpless victim. And your petitioners further pray that the King of Oude may be permitted freely to correspond with your petitioners in this country, so that they may also have opportunity of vindicating here the character and conduct of their sovereign and relative, of establishing his innocence of any offence against the crown of England, or the British government or people, and of shewing that, under every varying phase of circumstance, the royal family of Oude have continued steadfast and true to their friendship with the British nation.

‘And your petitioners will ever pray, &c.’

Some time after the presentation of this petition and memorial, a curious proof was afforded of the complexity and intrigue connected with the family affairs of the princes of India. A statement having gone abroad to the effect that a son of the King of Oude had escaped from Lucknow during the troubles of the Revolt, a native representative of the family in London sought to set the public mind right on the matter. He stated that the king had had only three legitimate sons; that one of these, being an idiot, was confined to the zenana or harem at Lucknow; that the second died of small-pox when twelve years of age; that the third was the prince who had come to London with the queen-mother; and that if any son of the king had really escaped from Lucknow, he must have been illegitimate, a boy about ten years old. This communication was signed by Mahmoud Museehooddeen, residing at Paddington, and designating himself ‘Accredited Agent to his Majesty the King of Oude.’ Two days afterwards the same journal contained a letter from Colonel R. Ouseley, also residing in the metropolis, asserting that he was ‘Agent in Chief to the King of Oude,’ and that Museehooddeen had assumed a title to which he had no right.

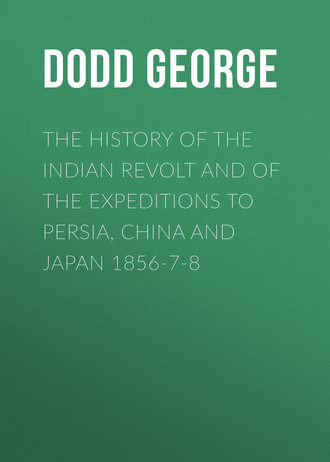

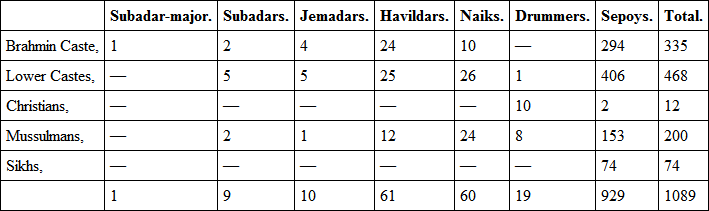

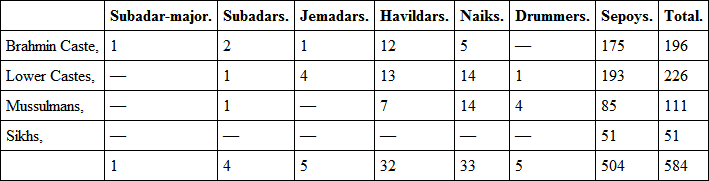

Castes and Creeds in the Indian Army. – The Indian officers being much divided in opinion concerning the relative insubordination of Mohammedans and Hindoos in the native regiments, it may be useful to record here the actual components of one Bengal infantry regiment, so far as concerns creed and caste. The information is obtained from an official document relating to the cartridge grievance, before the actual Revolt began.

The 34th regiment Bengal native infantry, just before its disbandment at Barrackpore in April, comprised 1089 men, distributed as follows:

The portion of this regiment present at Barrackpore – the rest being at Chittagong – when the mutinous proceedings took place, numbered 584, thus classified under four headings:

When 414 of these men were dismissed from the Company’s service, their religions appeared as follows:

It is not clearly stated how many Rajpoots, or men of the military caste, were included in the Hindoos who were not Brahmins.

If the regiment thus tabulated had been cavalry, instead of infantry, the preponderance, as implied in Chapter I., would have been wholly on the side of the Mussulmans.

CHAPTER X.

OUDE, ROHILCUND, AND THE DOAB: JUNE

The course of events now brings us again to that turbulent country, Oude, which proved itself to be hostile to the British in a degree not expected by the authorities at Calcutta. They were aware, it is true, that Oude had long furnished the chief materials for the Bengal native army; but they could not have anticipated, or at least did not, how close would be the sympathy between those troops and the Oude irregulars in the hour of tumult. Only seven months before the beginning of the Revolt, and about the same space of time after the formal annexation, a remarkable article on Indian Army Reform appeared in the Calcutta Review, attributed to Sir Henry Lawrence; in which he commented freely on the government proceedings connected with the army of Oude. He pointed out how great was the number of daring reckless men in that country; how large had been the army of the king before his deposition; how numerous were the small forts held by zemindars and petty chieftains, and guarded by nearly sixty thousand men; how perilous it was to raise a new British-Oudian army, even though a small one, solely from the men of the king’s disbanded regiments; how serious was the fact that nearly a hundred thousand disbanded warlike natives were left without employment; how prudent it would have been to send Oudians into the Punjaub, and Punjaubees into Oude; and how necessary was an increase in the number of British troops. The truth of these comments was not appreciated until Sir Henry himself was ranked among those who felt the full consequence of the state of things to which the comments referred. Oude was full of zemindars, possessing considerable resources of various kinds, having their retainers, their mud-forts, their arsenals, their treasures. These zemindars, aggrieved not so much by the annexation of their country, as by the manner in which territorial law-proceedings were made to affect the tenure of their estates, shewed sympathy with the mutineers almost from the first. The remarks of Mr Edwards, collector at Boodayoun, on this point, have already been adverted to (p. 115). The zemindars did not, as a class, display the sanguinary and vindictive passions so terribly evident in the reckless soldiery; still they held to a belief that a successful revolt might restore to them their former position and influence as landowners; and hence the formidable difficulties opposed by them to the military movements of the British.

Sir Henry Lawrence, as chief authority both military and civil in Oude, found himself very awkwardly imperiled at Lucknow in the early days of June. Just as the previous month closed, nearly all the native troops raised the standard of rebellion (see p. 96); the 13th, 48th, and 71st infantry, and the 7th cavalry, all betrayed the infection, though in different degrees; and of the seven hundred men of those four regiments who still remained faithful, he did not know how many he could trust even for a single day. The treasury received his anxious attention, and misgivings arose in his mind concerning the various districts around the capital, with their five millions of inhabitants. Soon he had the bitterness of learning that his rebellious troops, who had fled towards Seetapoor, had excited their brethren at that place to revolt. The Calcutta authorities were from that day very ill informed of the proceedings at Lucknow; for the telegraph wires were cut, and the insurgents stopped all dâks and messengers on the road. About the middle of the month, Colonel Neill, at Allahabad, received a private letter from Lawrence, sent by some secret agency, announcing that Seetapoor and Shahjehanpoor were in the hands of the rebels; that Secrora, Beraytch, and Fyzabad, were in like condition; and that mutinous regiments from all those places, as well as from Benares and Jounpoor, appeared to be approaching Lucknow on some combined plan of operations. He was strengthening his position at the Residency, but looked most anxiously for aid, which Neill was quite unable to afford him. Again, it became known to the authorities at Benares that Lawrence, on the 19th, still held his position at Lucknow; that he had had eight deaths by cholera; and that he was considering whether, aid from Cawnpore or Allahabad being unattainable, he could obtain a few reinforcements by steamer up the Gogra from Dinapoor. Another letter, but without date, reached the chief-magistrate of Benares, to the effect that Lawrence had got rid of most of the remaining native troops, by paying them their due, and giving them leave of absence for three months; he evidently felt disquietude at the presence even of the apparently faithful sepoys in his place of refuge, so bitterly had he experienced the hollowness of all protestations on their part. He had been very ill, and a provisional council had been appointed in case his health should further give way. Although the Residency was the stronghold, the city and cantonment also were still under British control: a fort called the Muchee Bhowan, about three-quarters of a mile from the Residency, and consisting of a strong, turreted, castellated building, was held by two hundred and twenty-five Europeans with three guns. The cantonment was northeast of the Residency, on the opposite side of the river, over which were two bridges of approach. Sir Henry had already lessened from eight to four the number of buildings or posts where the troops were stationed – namely, the Residency, the Muchee Bhowan, a strong post between these two, and the dâk-bungalow between the Residency and the cantonment; but after the mutiny, he depended chiefly on the Residency and the Muchee Bhowan. News, somewhat more definite in character, was conveyed in a letter written by Sir Henry on the 20th of June. So completely were the roads watched, that he had not received a word of information from Cawnpore, Allahabad, Benares, or any other important place throughout the whole month down to that date; he knew not what progress was being made by the rebels, beyond the region of which Lucknow was more immediately the centre; he still held the fort, city, Residency, and cantonment, but was terribly threatened on all sides by large bodies of mutineers. On the 27th he wrote another letter to the authorities at Allahabad, one of the very few (out of a large number despatched) that succeeded in reaching their destination. This letter was still full of heart, for he told of the Residency and the Muchee Bhowan being still held by him in force; of cholera being on the decrease; of his supplies being adequate for two months and a half; and of his power to ‘hold his own.’ On the other hand, he felt assured that at that moment Lucknow was the only place throughout the whole of Oude where British influence was paramount; and that he dared not leave the city for twenty-four hours without danger of losing all his advantages. His sanguine, hopeful spirit shone out in the midst of all his trials; he declared that with one additional European regiment, and a hundred artillerymen, he could re-establish British supremacy in Oude; and he added, in a sportive tone, which shewed what estimate he formed of some, at least, of the contingent corps, ‘a thousand Europeans, a thousand Goorkhas, and a thousand Sikhs, with eight or ten guns, will thrash anything.’ The Sikhs were irregulars raised in the Punjaub; and throughout the contests arising out of the Revolt, their fidelity towards the government was seldom placed in doubt.