полная версия

полная версияThe History of the Indian Revolt and of the Expeditions to Persia, China and Japan 1856-7-8

The postal system had not been allowed to stagnate during the eight years under consideration. A commission had been appointed in 1850, to inquire into the best means of increasing the efficiency of the system; and under the recommendations of this commission, great improvements had been made. A director-general of the post-office for the whole of India had been appointed; a uniformity of rate irrespective of distance had been established (three farthings for a letter, and three half-pence for a newspaper); prepayment by postage-stamps had been substituted for cash payment; the privileges of official franking had been almost abolished; and a uniform sixpenny rate was fixed for letters between India and England. Here again the governor-general insists, not only that the Indian government had worked zealously, but that England herself had been outstripped in liberal policy. ‘In England, a single letter is conveyed to any part of the British isles for one penny; in India, a single letter is conveyed over distances immeasurably greater – from Peshawur, on the borders of Afghanistan, to the southernmost village of Cape Comorin, or from Dehooghur, in Upper Assam, to Kurachee at the mouth of the Indus – for no more than three farthings. The postage chargeable on the same letter three years ago in India would not have been less than one shilling, or sixteen times the present charge. Again, since uniform rates of postage between England and India have been established, the Scotch recruit who joins his regiment on our furthest frontier at Peshawur, may write to his mother at John o’ Groat’s House, and may send his letter to her free for sixpence: three years ago, the same sum would not have carried his letter beyond Lahore.’

So great had been the activity of the Company and the governor-general, in the course of eight years, in developing the productive resources of our Oriental empire, that a department of Public Works had become essentially necessary. The Company expended from two to three millions sterling annually in this direction, and a new organisation had been made to conduct the various works on which this amount of expenditure was to be bestowed. When the great roads and canals were being planned and executed, numerous civil engineers were of course needed; and the minute tells us that ‘it was the far-seeing sagacity of Mr Thomason which first anticipated the necessity of training engineers in the country itself in which they were to be employed, and which first suggested an effectual method of doing so. On his recommendation, the civil engineering college at Roorkee, which now rightly bears his honoured name, was founded with the consent of the Honourable Court. It has already been enlarged and extended greatly beyond its original limits. Instruction in it is given to soldiers preparing for subordinate employment in the Public Works department, to young gentlemen not in the service of government, and to natives upon certain conditions. A higher class for commissioned officers of the army was created some years ago, at the suggestion of the late Sir Charles Napier; and the government has been most ready to consent to officers obtaining leave to study there, as in the senior department at Sandhurst. Excellent fruit has already been borne by this institution; many good servants have already been sent forth into [from?] the department; and applications for the services of students of the Thomason College were, before long, received from other local governments.’ But this was not all: civil engineering colleges and classes were formed at Calcutta, Madras, Bombay, Lahore, and Poonah.

So greatly had the various public works on rivers and harbours, roads and canals, telegraphic and postal communications, increased the trade of India, that the shipping entries increased regularly year by year. There were about six hundred vessels, exclusive of trading craft, that ascended the Hoogly to Calcutta in 1847; by 1856, the number had augmented to twelve hundred; and the tonnage had risen in a still greater ratio.

What is the English nation to think of all this, and how reconcile it with the tragedies destined so soon to afflict that magnificent country? Here we find the highest representative of the British crown narrating and describing, in words too clear to be misunderstood, political and commercial advancements of a really stupendous kind, effected within the short period of eight years. We read of vast territories conquered, tributary states annexed, amicable relations with other states strengthened, territorial revenues increased, improved administration organised, the civil service purified, legislative reforms effected, prison-discipline improved, native colleges and schools established, medical aid disseminated, thuggee and dacoitee put down, suttee and infanticide discouraged, churches and chapels built, ministers of religion salaried. We are told of the cultivation of raw produce being fostered, the improvement of live-stock insured, the availability of mineral treasures tested, exact territorial surveys completed, stupendous irrigation and navigation canals constructed, flotillas of river-steamers established, ports and harbours enlarged and deepened, magnificent roads formed, long lines of railway commenced, thousands of miles of electric telegraph set to work, vast postal improvements insured. We read all this, and we cannot marvel if the ruler of India felt some pride in his share of the work. But still the problem remains unsolved – was the great Revolt foreshadowed in any of these achievements? As the mutiny began among the military, it may be well to see what information is afforded by the minute concerning military reforms between the years 1848 and 1856.

It is truly remarkable, knowing what the English nation now so painfully knows, that the Marquis of Dalhousie, in narrating the various improvements introduced by him in the military system, passes at once to the British soldiers: distinctly asserting that ‘the position of the native soldier in India has long been such as to leave hardly any circumstance of his condition in need of improvement.’ The British troops, we are told, had been benefited in many ways. The terms of service in India had been limited to twelve years as a maximum; the rations had been greatly improved; malt liquor had been substituted for destructive ardent spirits; the barracks had been mostly rebuilt, with modifications depending on the climate of each station; separate barracks had been set apart for the married men of each regiment; lavatories and reading-rooms had become recognised portions of every barrack; punkhas or cooling fans had been adopted for barracks in hot stations, and additional bed-coverings in cold; swimming-baths had been formed at most of the stations; soldiers’ gardens had been formed at many of the cantonments; workshops and tools for handicraftsmen had been attached to the barracks; sanitaria had been built among the hills for sick soldiers; and arrangements had been framed for acclimatising all recruits from England before sending them into hot districts on service. Then, as to the officers. Encouragement had been offered for the officers to make themselves proficient in the native languages. A principle had been declared and established, that promotion by seniority should no longer govern the service; but that the test should be ‘the selection of no man, whatever his standing, unless he was confessedly capable and efficient.’ With the consent of the Queen, the Company’s officers had had granted to them the recognition, until then rather humiliatingly withheld, of their military rank, not only in India but throughout the world. A military orphan school had been established in the hill districts. All the military departments had been revised and amended, the commissariat placed on a wholly new basis, and the military clothing supplied on a more efficient system than before.

Again is the search baffled. We find in the minute proofs only that India had become great and grand; if the seeds of rebellion existed, they were buried under the language which described material and social advancement. Is it that England, in 1856, had yet to learn to understand the native character? Such may be; for thuggee came to the knowledge of our government with astounding suddenness; and there may be some other kind of thuggee, religious or social, still to be learned by us. Let us bear in mind what this thuggee or thugism was, and who were the Thugs. Many years ago, uneasy whispers passed among the British residents in India. Rumours went abroad of the fate of unsuspecting travellers ensnared while walking or riding upon the road, lassoed or strangled by means of a silken cord, and robbed of their personal property; the rumours were believed to be true; but it was long ere the Indian government succeeded in bringing to light the stupendous conspiracy or system on which these atrocities were based. It was then found that there exists a kind of religious body in India, called Thugs, among whom murder and robbery are portions of a religious rite, established more than a thousand years ago. They worship Kali, one of the deities of the Hindoo faith. In gangs varying from ten to two hundred, they distribute themselves – or rather did distribute themselves, before the energetic measures of the government had nearly suppressed their system – about various parts of India, sacrificing to their tutelary goddess every victim they can seize, and sharing the plunder among themselves. They shed no blood, except under special circumstances; murder being their religion, the performance of its duties requires secrecy, better observed by a noose or a cord than by a knife or firearm. Every gang has its leader, teacher, entrappers, stranglers, and gravediggers; each with his prescribed duties. When a traveller, supposed or known to have treasure about him, has been inveigled to a selected spot by the Sothas or entrappers, he is speedily put to death quietly by the Bhuttotes or stranglers, and then so dexterously placed underground by the Lughahees or gravediggers that no vestige of disturbed earth is visible.1 This done, they offer a sacrifice to their goddess Kali, and finally share the booty taken from the murdered man. Although the ceremonial is wholly Hindoo, the Thugs themselves comprise Mohammedans as well as Hindoos; and it is supposed by some inquirers that the Mohammedans have ingrafted a system of robbery on that which was originally a religious murder – murder as part of a sacrifice to a deity.

We repeat: there may be some moral or social thuggee yet to be discovered in India; but all we have now to assert is, that the condition of India in 1856 did not suggest to the retiring governor-general the slightest suspicion that the British in that country were on the edge of a volcano. He said, in closing his remarkable minute: ‘My parting hope and prayer for India is, that, in all time to come, these reports from the presidencies and provinces under our rule may form, in each successive year, a happy record of peace, prosperity, and progress.’ No forebodings here, it is evident. Nevertheless, there are isolated passages which, read as England can now read them, are worthy of notice. One runs thus: ‘No prudent man, who has any knowledge of Eastern affairs, would ever venture to predict the maintenance of continued peace within our Eastern possessions. Experience, frequent hard and recent experience, has taught us that war from without, or rebellion from within, may at any time be raised against us, in quarters where they were the least to be expected, and by the most feeble and unlikely instruments. No man, therefore, can ever prudently hold forth assurance of continued peace in India.’ Again: ‘In territories and among a population so vast, occasional disturbance must needs prevail. Raids and forays are, and will still be, reported from the western frontier. From time to time marauding expeditions will descend into the plains; and again expeditions to punish the marauders will penetrate the hills. Nor can it be expected but that, among tribes so various and multitudes so innumerable, local outbreaks will from time to time occur.’ But in another place he seeks to lessen the force and value of any such disturbances as these. ‘With respect to the frontier raids, they are and must for the present be viewed as events inseparable from the state of society which for centuries past has existed among the mountain tribes. They are no more to be regarded as interruptions of the general peace in India, than the street-brawls which appear among the everyday proceedings of a police-court in London are regarded as indications of the existence of civil war in England. I trust, therefore, that I am guilty of no presumption in saying, that I shall leave the Indian Empire in peace, without and within.’

Such, then, is a governor-general’s picture of the condition of the British Empire in India in the spring of 1856: a picture in which there are scarcely any dark colours, or such as the painter believed to be dark. We may learn many things from it: among others, a consciousness how little we even now know of the millions of Hindostan – their motives, their secrets, their animosities, their aspirations. The bright picture of 1856, the revolting tragedies of 1857 – how little relation does there appear between them! That there is a relation all must admit, who are accustomed to study the links of the chain that connect one event with another; but at what point the relation occurs, is precisely the question on which men’s opinions will differ until long and dispassionate attention has been bestowed on the whole subject.

Notes[This may be a convenient place in which to introduce a few observations on three subjects likely to come with much frequency under the notice of the reader in the following chapters; namely, the distances between the chief towns in India and the three great presidential cities – the discrepancies in the current modes of spelling the names of Indian persons and places – and the meanings of some of the native words frequently used in connection with Indian affairs.]

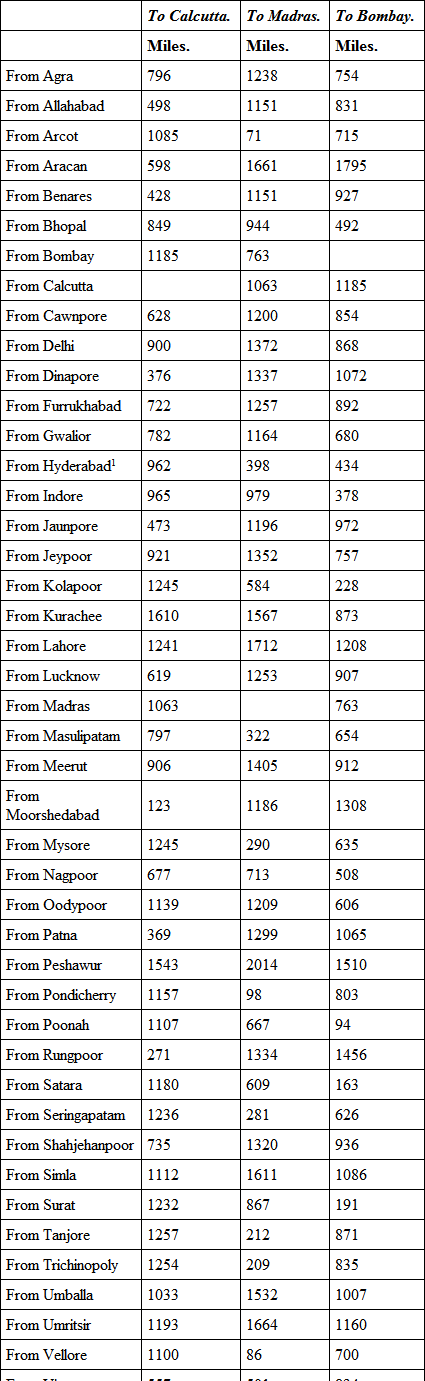

Distances.– For convenience of occasional reference, a table of some of the distances in India is here given. It has been compiled from the larger tables of Taylor, Garden, Hamilton, and Parbury. Many of the distances are estimated in some publications at smaller amount, owing, it may be, to the opening of new and shorter routes:

1There are two Hyderabads – one in the Nizam’s dominions in the Deccan, and the other in Sinde (spelt Hydrabad): it is the former here intended.

Orthography.– It is perfectly hopeless to attempt here any settlement of the vexed question of Oriental orthography, the spelling of the names of Indian persons and places. If we rely on one governor-general, the next contradicts him; the commander-in-chief very likely differs from both; authors and travellers have each a theory of his own; while newspaper correspondents dash recklessly at any form of word that first comes to hand. Readers must therefore hold themselves ready for these complexities, and for detecting the same name under two or three different forms. The following will suffice to shew our meaning: – Rajah, raja – nabob, nawab, nawaub – Punjab, Punjaub, Penjab, Panjab – Vizierabad, Wuzeerabad – Ghengis Khan, Gengis Khan, Jengis Khan – Cabul, Caboul, Cabool, Kabul – Deccan, Dekkan, Dukhun – Peshawur, Peshawar – Mahomet, Mehemet, Mohammed, Mahommed, Muhummud – Sutlej, Sutledge – Sinde, Scinde, Sindh – Himalaya, Himmaléh – Cawnpore, Cawnpoor – Sikhs, Seiks – Gujerat, Guzerat – Ali, Alee, Ally – Ghauts, Gauts – Sepoys, Sipahis – Faquir, Fakeer – Oude, Oudh – Bengali, Bengalee – Burhampooter, Brahmaputra – Asam, Assam – Nepal, Nepaul – Sikkim, Sikim – Thibet, Tibet – Goorkas, Ghoorkas – Cashmere, Cashmeer, Kashmir – Doab, Dooab – Sudra, Soodra – Vishnu, Vishnoo – Buddist, Buddhist, &c. Mr Thornton, in his excellent Gazetteer of India, gives a curious instance of this complexity, in eleven modes of spelling the name of one town, each resting on some good authority – Bikaner, Bhicaner, Bikaneer, Bickaneer, Bickanere, Bikkaneer, Bhikanere, Beekaneer, Beekaner, Beykaneer, Bicanere. One more instance will suffice. Viscount Canning, writing to the directors of the East India Company concerning the conduct of a sepoy, spelled the man’s name Shiek Paltoo. A fortnight afterwards, the same governor-general, writing to the same directors about the same sepoy, presented the name under the form Shaik Phultoo. We have endeavoured as far as possible to make the spelling in the narrative and the map harmonise.

Vocabulary.– We here present a vocabulary of about fifty words much used in India, both in conversation and in writing, connected with the military and social life of the natives; with the initials or syllables P., Port., H., M., A., T., Tam., S., to denote whether the words have been derived from the Persian, Portuguese, Hindustani, Mahratta, Arabic, Tatar, Tamil, or Sanscrit languages. Tamil or Tamul is spoken in some of the districts of Southern India. In most instances, two forms of spelling are given, to prepare the reader for the discrepancies above adverted to:

Ab, aub (P.), water; used in composition thus: Punjaub, five waters, or watered by five rivers; Doab, a district between two rivers, equivalent in meaning to the Greek Mesopotamia.

Abad (P.), inhabited; a town or city; such as Allahabad, city of God; Hyderabad, city of Hyder.

Ayah (Port.), a nurse; a female attendant on a lady.

Baba (T.), a term of endearment in the domestic circle, nearly equivalent to the English dear, and applied both to a father and his child.

Baboo, a Hindoo title, equivalent to our Esquire.

Bag, bágh, a garden; Kudsiya bágh is a celebrated garden outside Delhi.

Bahadoor (P.), brave; a title of respect added to the names of military officers and others.

Bang (P.), an intoxicating potion made from hemp.

Bazar, bazaar, an exchange or market-place.

Begum (T.), a princess, a lady of high rank.

Bheestee, bihishtí, a water-carrier.

Bobachee, báwarchí (T.), an Indian officer’s cook.

Budgerow, bajrá (S.), a Ganges boat of large size.

Bungalow, banglá (H.), a house or dwelling.

Cherry, cheri (Tam.), village or town; termination to the name of many places in Southern India; such as Pondicherry.

Chit, chittí (H.), a note or letter.

Chupatty, chápátí (P.), a thin cake of unleavened Indian-corn bread.

Coolie, kuli (T.), a porter or carrier.

Cutcherry, kacharí (H.), an official room; a court of justice.

Dacoit, dákáit (H.), a gang-robber.

Dâk, dahk, dawk (H.), the Indian post, and the arrangements connected with it.

Dewan, a native minister or agent.

Dost (P.), a friend.

Feringhee, a Frank or European.

Fakeer, fakír (A.), a mendicant devotee.

Ghazee, ghazi (A.), a true believer who fights against infidels: hence Ghazeepoor, city of the faithful.

Golundauze, golandáz (P.), a native artilleryman.

Havildar (P.), a native sergeant.

Jehad (A.), a holy war.

Jemadar (P.), a native lieutenant.

Jhageerdar, jaghiredar, jágírdár (P.), the holder of land granted for services.

Mohurrum (A.), a fast held sacred by Mohammedans on the tenth day of the first month in their year, equivalent to the 25th of July.

Musjid (A.), a mosque; thence jumma musjid or jum’aah masjid, a cathedral or chief mosque.

Naik, naig (S.), a native corporal.

Náná, nena (M.), grandfather, a term of respect or precedence among the Mahrattas; Náná Sahib, so far from being a family or personal name, is simply a combination of two terms of respect (see Sahib) for a person whose real name was Dhundu Punt.

Nawab, nabob, núwáb (A.), derived from náib, a viceroy or vicegerent.

Nuddee, nadi (S.), a river.

Nullah, nálá (H.), a brook, water-course, the channel of a torrent.

Patam, pattanam (S.), a town; the termination of the names of many places in Southern India; such as Seringapatam, the city of Shrí Ranga, a Hindoo divinity.

Peon (P.), a messenger or foot-attendant.

Pore, poor, a town; the final syllable in many significant names, such as Bhurtpore or Bharatpoor, the town of Bharata.

Rajpoot, a Hindoo of the military caste or order; there is one particular province in Upper India named from them Rajpootana.

Ryot, a peasant cultivator.

Sahib, saheb, sáaib (A.), lord; a gentleman.

Sepoy, sípahí, in the Bengal presidency, a native soldier in the Company’s service; in that of Bombay, it often has the meaning of a peon or foot-messenger.

Shahzadah (P.), prince; king’s son.

Sowar (P.), a native horseman or trooper.

Subadar, soubahdar (A.), a native captain.

Tuppal, tappál (H.), a packet of letters; the post.

Zemindar, zamindár (P.), a landowner.

CHAPTER I.

THE ANGLO-INDIAN ARMY AT THE TIME OF THE OUTBREAK

The magnificent India which began to revolt from England in the early months of 1857; which continued that Revolt until it spread to many thousands of square miles; which conducted the Revolt in a manner that appalled all the civilised world by its unutterable horrors – this India was, after all, not really unsound at its core. It was not so much the people who rebelled, as the soldiers. Whatever grievances the hundred and seventy millions of human beings in that wonderful country may have had to bear; whatever complaints may have been justifiable on their parts against their native princes or the British government; and whatever may have been the feelings of those native princes towards the British – all of which matters will have to be considered in later chapters of this work – still it remains incontestable that the outbreak was a military revolt rather than a national rebellion. The Hindoo foot-soldier, fed and paid by the British, ran off with his arms and his uniform, and fought against those who had supported him; the Mohammedan trooper, with his glittering equipments and his fine horse, escaped with both in like manner, and became suddenly an enemy instead of a friend and servant. What effect this treachery may have had on the populace of the towns, is another question: we have at present only to do with the military origin of the struggle.

Here, therefore, it becomes at once necessary that the reader should be supplied with an intelligible clue to the series of events, a groundwork on which his appreciation of them may rest. As this work aims at something more than a mere record of disasters and victories, all the parts will be made to bear some definite relation one to another; and the first of these relations is – between the mutinous movements themselves, and the soldiers who made those movements. Before we can well understand what the sepoys did, we must know who the sepoys are; before we can picture to ourselves an Indian regiment in revolt, we must know of what elements it consists, and what are its usages when in cantonments or when on the march; and before we can appreciate the importance of two presidential armies remaining faithful while that of Bengal revolted, we must know what is meant by a presidency, and in what way the Anglo-Indian army bears relation to the territorial divisions of India. We shall not need for these purposes to give here a formal history of Hindostan, nor a history of the rise and constitution of the East India Company, nor an account of the manners and customs of the Hindoos, nor a narrative of the British wars in India in past ages, nor a topographical description of India – many of these subjects will demand attention in later pages; but at present only so much will be touched upon as is necessary for the bare understanding of the facts of the Revolt, leaving the causes for the present in abeyance.