полная версия

полная версияThe History of the Indian Revolt and of the Expeditions to Persia, China and Japan 1856-7-8

Another instance, somewhat analogous to this, was presented in the Punjaub. During the early days of the Revolt, the 36th and 61st Bengal regiments at Jullundur, and the 3d at Phillour, were among those which mutinied. Some of the sepoys in each, however, remained free from the taint; they stood faithful under great temptation. At a later date even these men were disarmed, from motives of policy; and they had none but nominal duties intrusted to them. At length Sir John Lawrence, finding that these men had passed through the ordeal honourably, proposed that they should be re-armed, and noticed in a way consistent with their merits. This was agreed to. About three hundred and fifty officers and men, the faithful exceptions of three unfaithful regiments, were formed into a special corps to be called the Wufadar Pultun or ‘faithful regiment.’ This new corps was to be in four companies, organised on the same footing as the Punjaub irregular infantry; and was to be stationed at some place where the men would not have their feelings wounded and irritated by the taunts of the Punjaubee soldiery – between whom and the Hindustani sepoys the relations were anything but amicable. Any of the selected number who preferred it, might receive an honourable discharge from the army instead of entering any new corps. The experiment was regarded as an important one; seeing that it might afford a clue to the best mode of dealing with the numerous disarmed sepoys in the Punjaub.

The Bombay presidency was not so closely engaged in political and military matters as to neglect the machinery of peaceful industry, the stay and support of a nation. Another of those paths to commerce and civilisation, railways, was opened for traffic in India in June. It was a portion of a great trunk-line which, when completed, would connect Bombay with Madras. The length opened was from Khandalla to Poonah; and this, with another portion opened in 1853, completed a route from Bombay to Poonah, excepting a long tunnel under the range of hills called the Bhore Ghauts, which was not expected to be completed until 1860. On the day of ceremonial opening, a journey was made from Bombay to Poonah and back in eighteen hours, including four hours of portage or porterage at the Bhore Ghauts. There were intermediate stations at Kirkee and Tulligaum. The Company organised a scheme including conveyance across the ghauts, by palkees and gharries, as part of their passenger contract. An instructive index to the advancing state of society in India was afforded by the fact, that one of the great Parsee merchants of Bombay, Cursetjee Jamsetjee, was the leading personage in the hospitalities connected with this railway-opening ceremonial.

A few remarks on the sister presidency, and this chapter may close.

If Madras, now as in former months, was wholly spared from fighting and treason, it at least furnished an instance of the difficulty attending any collision on religious matters with the natives. The Wesleyan missionaries had a chapel and school in the district of Madras city called Royapettah. Many native children attended the school, for the sake of the secular instruction there given, without becoming formal converts. One of them, a youth of fifteen or sixteen, mentioned to the Rev. Mr Jenkins, the Wesleyan minister, his wish to become a Christian; it was found on inquiry, however, that the parents were averse to this; and Mr Jenkins left it to the youth whether he would join the mission or return to his parents. He chose the former course. Hereupon a disturbance commenced among the friends of the family; this was put down by the police; but as the youth remained at the mission-house, the religious prejudices of the natives became excited, and the disturbance swelled into a riot. A mob collected in front of the mission-house, entered the compound, threw stones and bricks at the house, forced open the door, and broke all the furniture. Mr Jenkins and another missionary named Stephenson, retreated from room to room, until they got into the bathroom, and then managed to climb over a wall into another compound, where they found protection. It was a mere local and temporary riot, followed by the capture of some of the offenders and the escape of others; but it was just such a spark as, in other regions of India, might have set a whole province into a flame. The missionaries, estimating the youth’s age at seventeen or eighteen years, claimed for him a right of determining whether he would return to his parents (who belonged to the Moodelly caste), or enter the mission; whereas some of the zealots on the other side, declaring that his age was only twelve or thirteen, advocated the rightful exercise of parental authority. The magistrates, without entering into this question of disputed figures, recommended to the missionaries the exercise of great caution, in any matters likely to arouse the religious animosity of the natives; and there can be little doubt that, in the prevailing state of native feeling, such caution was eminently necessary.

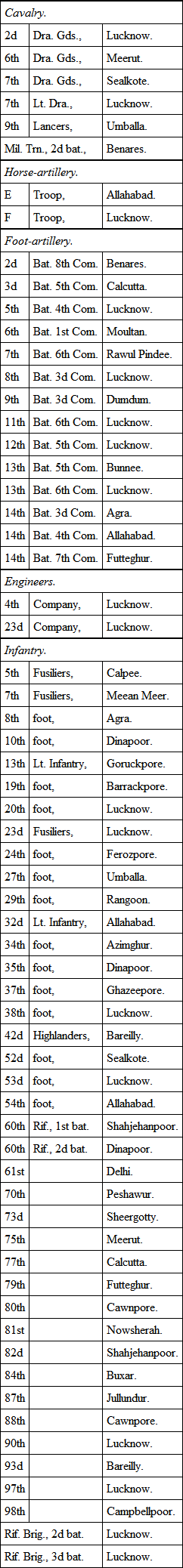

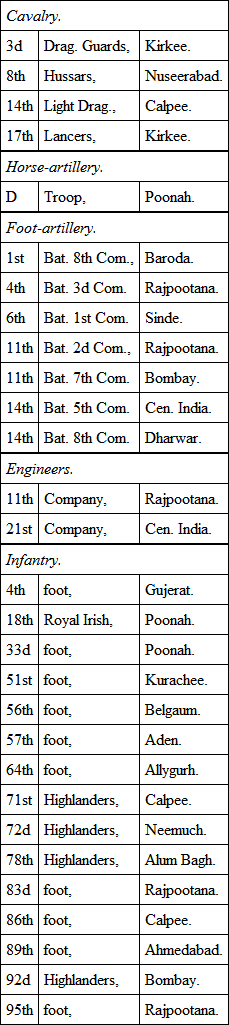

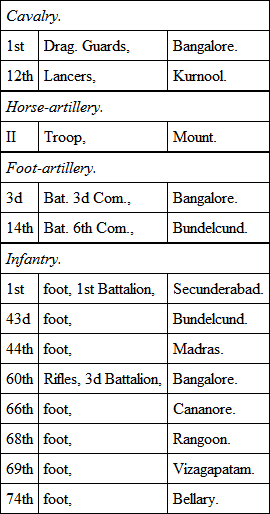

NoteQueen’s Regiments in India in June. – Sufficient has been said in former chapters to convey some notion of the European element in the Indian army in past years; the necessity for increasing the strength of that element; the relation between the Queen’s troops and the Company’s troops; the difficulty of sparing additional troops from England; the mode in which that difficulty was overcome; and the controversy concerning the best route for troop-ships. It seems desirable to add here a few particulars concerning the actual number of European troops in India at or about the time to which this chapter relates, and the localities in which they were stationed.

The following list, correct as to the regiments, is liable to modification in respect of localities. Many of the regiments were at the time in detachments, serving in different places; in such cases, the station of the main body only is named. Other regiments were at the time on the march; these are referred to the station towards which they were marching.

QUEEN’S TROOPS IN THE BENGAL ARMYIt may here be remarked, that the distinctions between ‘fusiliers,’ ‘foot,’ ‘light infantry,’ ‘Highlanders,’ and ‘rifles,’ are more nominal than real; these are all infantry regiments of the line, with a special number attached to each – except the particular corps called the ‘Rifle Brigade.’

The preceding list, relating to the Bengal army, gives the names and localities of regiments for the later weeks of June; the following, having reference to the Bombay army, applies to the earlier part of the same month; but the difference in this respect cannot be considerable.

The following list applies to the state of affairs about the third week in June:

Summing up these entries, it will be seen that out of the 99 regiments of the line in the British army (the 100th, a new Canadian regiment, had not at that time completed its organisation), no less than 59 were in India in June 1858; with a proportion of the other branches of the military service. Nothing can more strikingly illustrate the importance attached to the state of our Indian possessions.

On the 1st of January 1857, there were about 26,000 royal troops and 12,00 °Company’s European troops in India. During the ensuing fifteen months, to April 1858, there were sent over 42,000 royal troops and 500 °Company’s Europeans. These would have given a total of 85,000 British troops in India; but it was estimated that war, sickness, and heat had lessened this number to 50,000 available effective men. At that time the arrangements of the English authorities were such as to insure the speedy increase of this European element to not less than 70,000 men; and during the summer, still further advances were made in the same direction.

CHAPTER XXXII.

GRADUAL PACIFICATION IN THE AUTUMN

If the events of the three months – July, August, and September, 1858 – be estimated without due consideration, it might appear that the progress made in India was hardly such as could fairly be called ‘pacification.’ When it is found how frequently the Jugdispore rebels are mentioned in connection with the affairs of Behar; how numerous were the thalookdars of Oude still in arms; how large an insurgent force the Begum held under her command; how fruitless were all the attempts to capture the miscreant Nena Sahib; how severely the friendly thalookdars and zemindars of Oude were treated by those in the rebel ranks, as a means of deterring others from joining the English; how active was Tanteea Topee in escaping from Roberts and Napier, Smith and Michel, with his treasure plundered from the Maharajah Scindia; how many petty chieftains in the Bundelcund and Mahratta territories were endeavouring to raise themselves in power, during a period of disorder, by violence and plunder – there may be some justification for regarding the state of India as far from peaceful during those three months. But notwithstanding these appearances, the pacification of the empire was unquestionably in progress. The Bengal sepoys, the real mutineers, were becoming lessened in number every week, by the sword, the bullet, the gallows, and privation. The insurgent bands, though many and apparently strong, consisted more and more exclusively of rabble ruffians, whose chief motive for action was plunder, and who seldom ventured to stand a contest even with one-twentieth part their number of English troops. The regiments and drafts sent out from England, both to the Queen’s and the Company’s armies, were regularly continued, so as to render it possible to supply a few British troops to all the points attacked or troubled. There was a steady increase in the number of Jâts, Goorkhas, Bheels, Scindians, Beloochees, &c., enlisted in British service, having little or no sympathy with the high-caste Hindustani Oudians who had been the authors of so much mischief. There was a re-establishment of civil government in all the provinces, and (excepting Oude) in nearly all the districts of each province; attended by a renewal of the revenue arrangements, and by the maintenance of police bodies who aided in putting down rebels and marauders. There was an almost total absence of anything like nationality in the motions of the insurgents, or unity of purpose in their proceedings; the decrepit Emperor of Delhi, and the half-witted King of Oude, both of them prisoners, had almost gone out of the thoughts of the natives – who, so far as they rebelled at all, looked out for new leaders, new paymasters, new plunder. In short, the British government had gained the upper hand in every province throughout India; and preparations were everywhere made to maintain this hold so firmly, that the discomfiture of the rebels became a matter almost of moral certainty. Much remained to be done, and much time would be needed for doing it; but the ‘beginning of the end’ was come, and men could speak without impropriety of the gradual pacification of India.

The events of these three months will not require any lengthened treatment; of new mutinies there was only one; and the military and other operations will admit of rapid recital.

Calcutta saw nothing of Viscount Canning during the spring, summer, and autumn. His lordship, as governor-general, appreciated the importance of being near Sir Colin Campbell, to consult with him daily on various matters affecting the military operations in the disturbed districts. Both were at Allahabad throughout the period to which this chapter relates. The supreme council, however, remained at the presidential capital, giving effect to numerous legislative measures, and carrying on the regular government of the presidency. Calcutta was now almost entirely free from those panics which so frequently disturbed it during the early months of the mutiny; rapine and bloodshed did not approach the city, and the English residents gradually sobered down. Although the violent and often absurd opposition to the governor-general had not quite ceased, it had greatly lessened; the dignified firmness of Lord Canning made a gradual conquest. Some of the newspapers, here as at Bombay, invented proclamations and narratives, crimes and accusations, with a disregard of truth which would hardly have been shewn by any journals in the mother-country; and those effusions which were not actually invented, too often received a colour ill calculated to convey a correct idea of their nature. Many of the journalists never forgot or forgave the restrictions which the governor-general deemed it prudent to place on the press in the summer of 1857; the amount of anonymous slander heaped on him was immense. One circumstance which enabled his lordship to live down the calumnies, was the discovery, made by the journalists in the following summer, that Lord Derby’s government was not more disposed than that of Lord Palmerston to expel Viscount Canning from office – a matter which will have to be noticed more fully in another chapter. The more moderate journalists of the Anglo-Indian press, it must in fairness be stated, did their part towards bringing about a more healthy state of feeling.

That the authorities at Calcutta were not insensible to the value of newspapers and journals, in a region so far away from England, was shewn by an arrangement made in the month of August – which afforded at the same time a quiet but significant proof of an improved attention towards the well-being of soldiers. An order was issued that a supply of newspapers and periodicals should be forwarded to the different military hospitals in Calcutta at the public expense. Those for the officers’ hospital173 comprised some magazines of a higher class than were included in the list for the men’s hospitals; but such were to be sent afterwards to the men’s hospitals, when the officers had perused them.

In connection with military matters, in and near the presidential city, it may be mentioned that the neighbourhood of Calcutta was the scene of a settlement or colonisation very novel, and as unsatisfactory as it was novel. It has been the custom to send over a small number of soldiers’ wives with every British regiment sent to our colonies or foreign territories. During the course of twelve months so many regiments arrived at Calcutta, that these soldiers’ wives accumulated to eighteen hundred in number. They were consigned to the station at Dumdum, a few miles north of Calcutta; and were attended by three or four surgeons and one Protestant chaplain. The accommodation provided for them was sufficient for the women themselves, but not for the children, who added greatly to their number. Many of these women, being of that ignorant and ill-regulated class from which soldiers too frequently choose their wives, brought with them dirty habits and drinking tendencies; and these, when the fierce heat of an Indian summer came, engendered dysentery and diarrhœa, from which diseases a large number of women and children died. Other irregularities of conduct appeared, among a mass of women so strangely separated from all home-ties; and arrangements were gradually made for breaking up this singular colony.

The details given in former chapters, especially in the ‘notes,’ will have shewn how large was the number of regiments conveyed from the United Kingdom and the colonies to India; and when it is remembered that far more of these landed at Calcutta than at Madras, Bombay, or Kurachee, it will easily be understood how military an aspect they gave to the first-named city. Still, numerous as they were, they were never equal to the demand. Without making any long stay at Calcutta, they marched to the scenes of action in the northwest. In the scarcity of regular troops, the Bengal government derived much valuable services from naval and marine brigades – men occupying a middle position between soldiers and sailors. Captain Sir William Peel’s naval brigade has been often mentioned, in connection with gallant achievements in Oude; and Captain Sotheby’s naval brigade also won a good name, in the provinces eastward of Oude. But besides these, there were about a dozen different bodies in Bengal, each consisting of a commandant, two under-officers, a hundred men, and two light field-guns. Being well drilled, and accustomed to active movements, these parties were held in readiness to march off at short notice to any districts where a few resolute disciplined men could overawe turbulent towns-people; and thus they held the eastern districts in quietness without drawing on the regular military strength of the presidency. The Shannon naval brigade acquired great fame; the heroic Peel had made himself a universal favourite, and the brigade became a noted body, not only for their own services, but for their connection with their late gallant commander. When the brigade returned down the Ganges, the residents of Calcutta gave them a public reception and a grand dinner. Sir James Outram was present at the dinner, and, in a graceful and appropriate way, told of his own experience of the services of the brigade at Lucknow in the memorable days of the previous winter. ‘Almost the first white faces I saw, when the lamented Havelock and I rushed out of our prison to greet Sir Colin at the head of our deliverers, were the hearty, jolly, smiling faces of some of you Shannon men, who were pounding away with two big guns at the palace; and I then, for the first time in my life, had the opportunity of seeing and admiring the coolness of British sailors under fire. There you were, working in the open plains, without cover, or screen, or rampart of any kind, your guns within musket-range of the enemy, as coolly as if you were practising at the Woolwich target. And that it was a hot fire you were exposed to, was proved by three of the small staff that accompanied us (Napier, young Havelock, and Sitwell) being knocked over by musket-balls in passing to the rear of those guns, consequently further from the enemy than yourselves.’ Such a speech from such a man was about the most acceptable compliment that the brigade could receive, and was well calculated to produce a healthy emulation in other quarters.

The authorities at all the stations were on the watch for any symptoms which, though trivial in themselves, might indicate the state of feeling among the soldiery or the natives generally. Thus, on the 10th of July, at Barrackpore, a chuprassee happening to go down to a tank near the lines, saw a bayonet half in and half out of the water. A search was thereupon ordered; when about a hundred weapons – muskets, sabres, and bayonets – with balls and other ammunition – were discovered at the bottom of the tank. These warlike materials were rendered almost valueless by the action of the water; but their presence in the tank was not the less a mystery needing to be investigated. The authorities, in this as in many similar cases, thought it prudent not to divulge the results of their investigation.

The great jails of India were a source of much trouble and anxiety during the mutiny. All the large towns contained such places of incarceration, which were usually full of very desperate characters; and these men were rejoiced at any opportunity of revenging themselves on the authorities. Such opportunities were often afforded; for, as we have many times had occasion to narrate, the mutineers frequently broke open the jails as a means of strengthening their power by the aid of hundreds or thousands of budmashes ready for any atrocities. So late as the 31st of July, at Mymensing, in the eastern part of Bengal, the prisoners in the jail, six hundred in number, having overpowered the guard, escaped, seized many tulwars and muskets, and marched off towards Jumalpore. The Europeans at this place made hurried preparations for defence, and sent out such town-guards and police as they could muster, to attack the escaped prisoners outside the station. About half of the number were killed or recaptured, and the rest escaped to work mischief elsewhere. It is believed, however, that in this particular case, the prisoners had no immediate connection with rebels or mutinous sepoys; certain prison arrangements concerning food excited their anger, and under the influence of this anger they broke forth.

So far as concerns actual mutiny, the whole province of Bengal was nearly exempt from that infliction during the period now under consideration; regular government was maintained, and very few rebels troubled the course of peaceful industry.

Behar, however, was not so fortunate. Situated between Bengal and Oude, it was nearer to the scenes of anarchy, and shared in them more fully. Sir Edward Lugard, as we have seen, was employed there during the spring months; but having brought the Jugdispore rebels, as he believed, to the condition of mere bandits and marauders, he did not think it well to keep his force in active service during the rainy season, when they would probably suffer more from inclement weather than from the enemy. He resigned command, on account of his shattered health, and his Azimghur field-force was broken up. The 10th foot, and the Madras artillery, went to Dinapoor; the 84th foot and the military train, under Brigadier Douglas, departed for Benares; the royal artillery were summoned to Allahabad; the Sikh cavalry and the Madras rifles went to Sasseram; and the Madras cavalry to Ghazeepore. Captain Rattray, with his Sikhs, was left at Jugdispore, whence he made frequent excursions to dislodge small parties of rebels.

A series of minor occurrences took place in this part of Behar, during July, sufficient to require the notice of a few active officers at the head of small bodies of reliable troops, but tending on the other hand to shew that the military power of the rebels was nearly broken down – to be followed by the predatory excursions of ruffian bands whose chief or only motive was plunder. On the 8th a body of rebels entered Arrah, fired some shot, and burnt Mr Victor’s bungalow; the troops at that station being too few to effectually dislodge them, a reinforcement was sent from Patna, which drove them away. Brigadier Douglas was placed in command of the whole of this disturbed portion of Behar, from Dinapoor to Ghazeepore, including the Arrah and Jugdispore districts; and he so marshalled and organised the troops placed at his disposal as to enable him to bring small bodies to act promptly upon any disturbed spots. He established strong posts at moderate distances in all directions. The rebels in this quarter having few or no guns left, Douglas felt that their virtual extinction, though slow, would be certain. He was constantly on the alert; insomuch that the miscreants could never remain long to work mischief in one place. Meghur Singh, Joodhur Singh, and many other ‘Singhs,’ headed small bands at this time. On the 17th, Captain Rattray had a smart encounter with some of these people at Dehree, or rather, it was a capture, with scarcely any encounter at all. His telegram to Allahabad described it very pithily: ‘Sangram Singh having committed some murders in the neighbourhood of Rotas, and the road being completely closed by him, I sent out a party of eight picked men from my regiment, with orders to kill or bring in Sangram Singh. This party succeeded most signally. They disguised themselves as mutinous sepoys, brought in Sangram Singh last night, and killed his brother (the man who committed the late murders by Sangram Singh’s orders), his sons, nephew, and grandsons, amounting in all to nine persons – bringing in their heads. At this capture, all the people of the south [of the district?] are much rejoiced. The hills for the present are clear from rebels. I shall try Sangram Singh to-morrow.’ The trunk-road from Calcutta to the upper provinces, about Sasseram, Jehanabad, Karumnassa, and other places, was frequently blocked by small parties of rebels or marauders; and then it became necessary to send out detachments to disperse them. As it was of immense importance to maintain this road open for traffic, military and commercial, the authorities, at Patna, Benares, and elsewhere, were on the alert to hunt down any predatory bands that might make their appearance.