полная версия

полная версияFragments of Earth Lore: Sketches & Addresses Geological and Geographical

If the student of the Pleistocene faunas has certain advantages in the fact that he has to deal with forms many of which are still living, he labours at the same time under disadvantages which are unknown to his colleagues who are engaged in the study of the life of far older periods. The Pleistocene period was distinguished above all things by its great oscillations of climate – the successive changes being repeated and producing correlative migrations of floras and faunas. We know that arctic and temperate faunas and floras flourished during interglacial times, and a like succession of life-forms followed the final disappearance of glacial conditions. A study of the organic remains met with in any particular deposit will not necessarily, therefore, enable us to assign these to their proper horizon. The geographical position of the deposit, and its relation to Pleistocene accumulations elsewhere, must clearly be taken into account. Already, however, much has been done in this direction, and it is probable that ere long we shall be able to arrive at a fair knowledge of the various modifications which the Pleistocene floras and faunas experienced during that protracted period of climatic changes of which I have been speaking. We shall even possibly learn how often the arctic, steppe-, prairie-, and forest-faunas, as they have been defined by Woldrich, replaced each other. Even now some approximation to this better knowledge has been made. Dr. Pohlig,46 for example, has compared the remains of the Pleistocene faunas obtained at many different places in Europe, and has presented us with a classification which, although confessedly incomplete, yet serves to show the direction in which we must look for further advances in this department of inquiry.

During the last twenty years the evidence of interglacial conditions both in Europe and America has so increased that geologists generally no longer doubt that the Pleistocene period was characterised by great changes of climate. The occurrence at many different localities on the Continent of beds of lignite and freshwater alluvia, containing remains of Pleistocene mammalia, intercalated between separate and distinct boulder-clays has left us no other alternative. The interglacial beds of the Alpine Lands of central Europe are paralleled by similar deposits in Britain, Scandinavia, Germany, and France. But opinions differ as to the number of glacial and interglacial epochs – many holding that we have evidence of only two cold stages and one general interglacial stage. This, as I have said, is the view entertained by most geologists who are at work on the glacial accumulations of Scandinavia and north Germany. On the other hand, Dr. Penck and others, from a study of drifts of the German Alpine Lands, believe that they have met with evidence of three distinct epochs of glaciation, and two epochs of interglacial conditions. In France, while some observers are of opinion that there have been only two epochs of general glaciation, others, as, for example, M. Tardy, find what they consider to be evidence of several such epochs. Others again, as M. Falsan, do not believe in the existence of any interglacial stages, although they readily admit that there were great advances and retreats of the ice during the Glacial period. M. Falsan, in short, believes in oscillations, but is of opinion that these were not so extensive as others have maintained. It is, therefore, simply a question of degree, and whether we speak of oscillations or of epochs, we must needs admit the fact that throughout all the glaciated tracts of Europe, fossiliferous deposits occur intercalated among glacial accumulations. The successive advance and retreat of the ice, therefore, was not a local phenomenon, but characterised all the glaciated areas. And the evidence shows that the oscillations referred to were on a gigantic scale.

The relation borne to the glacial accumulations by the old river alluvia which contain relics of palæolithic man early attracted attention. From the fact that these alluvia in some places overlie glacial deposits, the general opinion (still held by some) was that palæolithic man must needs be of post-glacial age. But since we have learned that all boulder-clay does not belong to one and the same geological horizon – that, in short, there have been at least two, and probably more, epochs of glaciation – it is obvious that the mere occurrence of glacial deposits underneath palæolithic gravels does not prove these latter to be post-glacial. All that we are entitled in such a case to say is simply that the implement-bearing beds are younger than the glacial accumulations upon which they rest. Their horizon must be determined by first ascertaining the relative position in the glacial series of the underlying deposits. Now, it is a remarkable fact that the boulder-clays which underlie such old alluvia belong, without exception, to the earlier stages of the Glacial period. This has been proved again and again, not only for this country but for Europe generally. I am sorry to reflect that some twenty years have now elapsed since I was led to suspect that the palæolithic deposits were not of post-glacial but of glacial and interglacial age. In 1871-72 I published a series of papers in the Geological Magazine in which were set forth the views I had come to form upon this interesting question. In these papers it was maintained that the alluvia and cave-deposits could not be of post-glacial age, but must be assigned to pre-glacial and interglacial times, and in chief measure to the latter. Evidence was led to show that the latest great development of glacier-ice in Europe took place after the southern pachyderms and palæolithic man had vacated England – that during this last stage of the Glacial period man lived contemporaneously with a northern and alpine fauna in such regions as southern France – and lastly, that palæolithic man and the southern mammalia never revisited north-western Europe after extreme glacial conditions had disappeared. These conclusions were arrived at after a somewhat detailed examination of all the evidence then available – the remarkable distribution of the palæolithic and ossiferous alluvia having, as I have said, particularly impressed me. I coloured a map to show at once the areas covered by the glacial and fluvio-glacial deposits of the last glacial epoch, and the regions in which the implement-bearing and ossiferous alluvia had been met with, when it became apparent that the latter never occurred at the surface within the regions occupied by the former. If ossiferous alluvia did here and there appear within the recently glaciated areas it was always either in caves, or as infra- or interglacial deposits. Since the date of these researches our knowledge of the geographical distribution of Pleistocene deposits has greatly increased, and implements and other relics of palæolithic man have been recorded from many new localities throughout Europe. But none of this fresh evidence contradicts the conclusions I had previously arrived at; on the contrary, it has greatly strengthened my general argument.

Professor Penck was, I think, the first on the Continent to adopt the views referred to. He was among the earliest to recognise the evidence of interglacial conditions in the drift-covered regions of northern Germany, and it was the reflections which those remarkable interglacial beds were so well calculated to suggest that led him into the same path as myself. Dr. Penck has published a map47 showing the areas covered by the earlier and later glacial deposits in northern Europe and the Alpine Lands, and indicating at the same time the various localities where palæolithic finds have occurred, and in not a single case do any of the latter appear within the areas covered by the accumulations of the last glacial epoch.

A glance at the papers which have been published in Germany within the last few years will show how greatly students of the Pleistocene ossiferous beds have been influenced by what is now known of the interglacial deposits and their organic remains. Professors Rothpletz48 and Andreæ,49 Dr. Pohlig50 and others, do not now hesitate to correlate with those beds the old ossiferous and implement-bearing alluvia which lie altogether outside of glaciated regions.

The relation of the Pleistocene alluvia of France to the glacial deposits of that and other countries has been especially canvassed. Rothpletz, in the paper I have cited, includes these alluvia amongst the interglacial deposits, and in the present year (1889) we have an interesting essay on the same subject by the accomplished secretary of the Anthropological and Archæological Congress which met recently in Paris. M. Boule51 correlates the palæolithic cave- and river-deposits of France with those of other countries, and shows that they must be of interglacial age. His classification, I am gratified to find, does not materially differ from that given by myself a number of years ago. He is satisfied that in France there is evidence of three glacial epochs and two well-marked interglacial horizons. The oldest of the palæolithic stages of Mortillet (Chelléenne) culminated according to Boule during the last interglacial epoch, while the more recent palæolithic stages (Moustérienne, Solutréenne, and Magdalénienne) coincided with the last great development of glacier-ice. The Palæolithic age, so far as Europe is concerned, came to a close during this last cold phase of the Glacial period.

There are many other points relating to glacial geology which have of late years been canvassed by Continental workers, but these I cannot discuss here. I have purposely indeed restricted my remarks to such parts of a wide subject as I thought might have interest for glacialists in this country, some of whom may not have had their attention directed to the results which have recently been attained by their fellow-labourers in other lands. Had time permitted I should gladly have dwelt upon the noteworthy advances made by our American brethren in the same department of inquiry. Especially should I have wished to direct attention to the remarkable evidence adduced in favour of the periodicity of glacial action. Thus Messrs. Chamberlin and Salisbury, after a general review of that evidence, maintain that the Ice Age was interrupted by one chief interglacial epoch and also by three interglacial sub-epochs or episodes of deglaciation. These authors discuss at some length the origin of the löss, and come to the general conclusion that while deposits of this character may have been formed at different stages of the Glacial period, and under different conditions, yet upon the whole they are best explained by aqueous action. Indeed a perusal of the recent geological literature of America shows a close accord between the theoretical opinions of many Transatlantic and European geologists.

Thus as years advance the picture of Pleistocene times becomes more and more clearly developed. The conditions under which our old palæolithic predecessors lived – the climatic and geographical changes of which they were the witnesses – are gradually being revealed with a precision that only a few years ago might well have seemed impossible. This of itself is extremely interesting, but I feel sure that I speak the conviction of many workers in this field of labour when I say that the clearing up of the history of Pleistocene times is not the only end which they have in view. One can hardly doubt that when the conditions of that period and the causes which gave rise to these have been more fully and definitely ascertained we shall have advanced some way towards the better understanding of the climatic conditions of still earlier periods. For it cannot be denied that our knowledge of Palæozoic, Mesozoic, and even early Cainozoic climates is unsatisfactory. But we may look forward to the time when much of this uncertainty will disappear. Meteorologists are every day acquiring a clearer conception of the distribution of atmospheric pressure and temperature and the causes by which that distribution is determined, and the day is approaching when we shall be better able than we are now to apply this extended meteorological knowledge to the explanation of the climates of former periods in the world’s history. One of the chief factors in the present distribution of atmospheric temperature and pressure is doubtless the relative position of the great land- and water-areas; and if this be true of the present, it must be true also of the past. It would almost seem, then, as if all one had to do to ascertain the climatic conditions of any particular period, was to prepare a map depicting with some approach to accuracy the former relative position of land and sea. With such a map could our meteorologists infer what the climatic conditions must have been? Yes, provided we could assure them that in other respects the physical conditions did not differ from the present. Now there is no period in the past history of our globe the geographical conditions of which are better known than the Pleistocene. And yet, when we have indicated these upon a map, we find that they do not give the results which we might have expected. The climatic conditions which they seem to imply are not such as we know did actually obtain. It is obvious, therefore, that some additional and perhaps exceptional factor was at work to produce the recognised results. What was this disturbing element, and have we any evidence of its interference with the operation of the normal agents of climatic change in earlier periods of the world’s history? We all know that various answers have been given to such questions. Whether amongst these the correct solution of the enigma is to be found, time will show. Meanwhile, as all hypothesis and theory must starve without facts to feed on, it behoves us as working geologists to do our best to add to the supply. The success with which other problems have been attacked by geologists forbids us to doubt that ere long we shall have done much to dispel some of the mystery which still envelopes the question of geological climates.

IX.

The Glacial Period and the Earth-Movement Hypothesis. 52

Perhaps no portion of the geological record has been more assiduously studied during the last quarter of a century than its closing chapters. We are now in possession of manifold data concerning the interpretation of which there seems to be general agreement. But while that is the case, there remain, nevertheless, certain facts or groups of facts which are variously accounted for. Nor have all the phenomena of the Pleistocene period received equal attention from those who have recently speculated and generalised on the subject of Pleistocene climate and geography. Yet, we may be sure, geologists are not likely to arrive at any safe conclusions as to the conditions that obtained in Pleistocene times, unless the evidence be candidly considered in all its bearings. No interpretation of that evidence which does not recognise every outstanding group of facts can be expected to endure. It may be possible to frame a plausible theory to account for some particular conspicuous phenomena, but should that theory leave unexplained a residuum of less conspicuous but nevertheless well-proved facts, then, however strongly it may be fortified, it must assuredly fall.

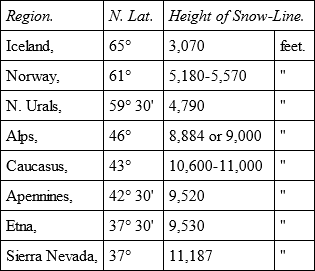

As already remarked, there are many phenomena in the interpretation of which geologists are generally agreed. It is, for example, no longer disputed that in Pleistocene times vast sheets of ice – continental mers de glace– covered broad areas in Europe and North America, and that extensive snow-fields and large local glaciers existed in many mountain-regions where snow-fields and glaciers are now unknown, or only meagrely developed. It is quite unnecessary, however, that I should give even the slightest sketch of the aspect presented by the glaciated tracts of our hemisphere at the climax of the Ice Age. The geographical distribution and extent of the old snow-fields, glaciers, and ice-sheets is matter now of common knowledge. It will be well, however, to understand clearly the nature of the conditions which obtained at the climax of glacial cold – at that stage, namely, when the Alpine glaciers reached their greatest development, and when so much of Europe was cased in snow and ice. This we shall best do by comparing the present with the past. Now in our day the limits of perennial snow are attained at heights that necessarily vary with the latitude. This is shown as follows: —

Thus in traversing Europe from north to south the snow-line may be said to rise from 3000 feet to 11,000 feet in round numbers. It is possible from such data to draw across the map a series of isochional lines, or lines of equal perennial snow, and this has been done by my friend, Professor Penck of Vienna.53 It will be understood that each isochional line traverses those regions above which the line of névé is estimated to occur at the same height. Thus the isochional line of 1000 metres (3280 feet) runs from the north of Norway down to lat. 64° on the west coast, whence it must pass west to the south of Iceland. The line of 1500 metres (4920 ft.) is traced from the north end of the Urals in a westerly direction. It then follows the back-bone of the Scandinavian peninsula, passes over to Scotland, and thence strikes west along lat. 55°. For each of these lines good data are obtainable. The line of 2000 metres (6560 ft.) is, however, hypothetical. It is estimated to extend from the Ural Mountains, about the lat. of 57°, over the mountains of middle Germany and above the north of France. The line of 2500 metres (8200 ft.) passes from the southern termination of the Urals, in lat. 51°, to the east Carpathians, thence along the north face of the Alps, thereafter south-west across the Cevennes to the north-west end of the Pyrenees; and thence above the Cantabrian and the Portuguese Highlands to the coast in lat. 39°. The line of 3000 metres (9840 ft.) is estimated to occur above the Caspian Sea, near lat. 44°, and extends west through the north end of the Caucasus to the Balkans. Thence it is traced north-west to the Alps, south-west to the Pyrenees, which range it follows to the west, and thereafter sweeps south above the coast at Cadiz. The line of 3500 metres (11,480 ft.) runs from the Caucasus south-west across Asia Minor to the Lebanon Mountains; thence it follows the direction of the Mediterranean, and traverses Morocco above the north face of the Atlas range. Finally the line of 4000 metres (13,120 feet) is estimated to trend in the same general direction as the last-mentioned line, but, of course, further to the south. Although these isochional lines are to some extent conjectural, yet the data upon which they are based are sufficiently numerous and well-known to prevent any great error, and we may admit that the lines represent with tolerable accuracy the general position of the snow-line over our Continent. So greatly has our knowledge of the glaciation of Europe increased during recent years, that the height of the snow-line of the Glacial period has been determined by MM. Simony, Partsch, Penck, and Höfer. Their method is simple enough. They first ascertain the lowest parts of a glaciated region from which independent glaciers have flowed. This gives the maximum height of the old snow-line. Next they determine the lowest point reached by such glaciers. It is obvious that the snow-line would occur higher up than that, but at a lower level than the actual source of the glaciers; and thus the minimum height of the former snow-line is approximately ascertained. The lowest level from which independent glaciers formerly flowed, and the terminal point reached by the highest-lying glaciers having been duly ascertained, it is possible to determine with sufficient accuracy the mean height of the old snow-line. The required data are best obtained, as one might have expected, in the Pyrenees and amongst the mountains of middle and southern Europe. In those regions the snow-line would seem to have been some 3000 feet or so lower than now. From such data Professor Penck has constructed a map showing the isochional lines of the Glacial period. These lines are, I need hardly say, only approximations, but they are sufficiently near the truth to bring out the contrast between the Ice Age and the present. Thus the isochional of 1000 metres, which at present lies above northern Scandinavia, was pushed south to the latitude of southern France and north Italy; while the isochional of 2000 metres (now overlying the extreme north of France and north Germany) passed in glacial times over the northern part of the Mediterranean.54

Isochional lines are not isotherms. Their height and direction are determined not only by temperature, but by the amount and distribution of the snow-fall. Nevertheless, the position of the snow-line in Europe during the Ice Age enables us to form a rough estimate of the temperature. At present in middle Europe the temperature falls 1° F. for every 300 feet of ascent. Hence if we take the average depression of the snow-line in glacial times at 3000 feet, that would correspond approximately to a lowering of the temperature by 10°.55 This may not appear to be much, but, as Penck points out, were the mean annual temperature to be lowered to that extent it would bring the climate of northern Norway down to southern Germany, and the climate of Sweden to Austria and Moravia, while that of the Alps would be met with over the basin of the Mediterranean.

Let it be noted further that this lowering of the temperature – this displacement of climatic zones, was experienced over the whole continent – extending on the one hand south into Africa, and on the other east into Asia. But while the conditions in northern and central Europe were markedly glacial, further south only more or less isolated snow-capped mountains and local glaciers appeared – such, for example, as those of the Sierra Nevada, the Apennines, Corsica, the Atlas, the Lebanon, etc. In connection with these facts we may note also that the Azores were reached by floating ice; and I need only refer in a word to the evidence of cold wet conditions as furnished by the plant and animal remains of the Pleistocene tufas, alluvia, and peat of southern Europe. Again in north Africa and Syria we find, in desiccated regions, widespread fluviatile accumulations, which, in the opinion of a number of competent observers, are indicative of rainy conditions contemporaneous with the Glacial period of Europe.

When we compare the conditions of the Ice Age with those of the present we are struck with the fact that the former were only an exaggeration of the latter. The development of glaciation was in strict accordance with existing conditions. Thus in Pleistocene times North America was more extensively glaciated than northern Europe, just as to-day Greenland shows more snow and ice than Scandinavia. No traces of glaciation have been observed as yet in northern Asia or in northern Alaska, and to-day the only glaciers and ice-sheets that exist in northern regions are confined to the formerly glaciated areas. Again, in Pleistocene Europe glacial phenomena were more strongly developed in the west than in the east. Large glaciers, for example, existed in central France, and a considerable ice-flow poured into the basin of the Douro. But in the same latitudes of eastern Europe we meet with few or no traces of ice-action. Again, the Vosges appear to have been more severely glaciated than the mountains of middle Germany; and so likewise the old glaciers of the western Alps were on a much more extensive scale than those towards the east end of the chain. Similar contrasts may be noted at the present day. Thus we find glaciers in Norway under lat. 60°, while in the Ural Mountains in the same latitude there is none. The glaciers of the western Alps, again, are larger than those in the eastern part of the chain. The Caucasus region, it is true, has considerable glaciers, but then the mountains are higher.

Now turn for a moment to North America. The eastern area was covered by one immense ice-sheet, while in the mountainous region of the west gigantic glaciers existed. In our own day we see a similar contrast. In the north-east lies Greenland well-nigh drowned in ice, while the north-west region on the other hand, although considerably higher and occurring in the same latitude, holds only local glaciers. We may further note that at the present day very dry regions, even when these are relatively lofty and in high latitudes, such as the uplands of Siberia, contain no glaciers. And the same was the case in the Glacial period. These facts are sufficient to show that the conditions of glacial times bore an intimate relation to those that now obtain. Could the requisite increase of precipitation and lowering of temperature take place, we cannot doubt that ice-sheets and glaciers would reappear in precisely the same regions where they were formerly so extensively developed. No change in the relative elevation of the land would be required – increased precipitation accompanied by a general lowering of the snow-line for 3000 or 3500 feet would suffice to reintroduce the Ice Age.