полная версия

полная версияThe Fiction Factory

The serial story, published in the Free Press in 1891, had made friends for Edwards. Among these friends was Alfred B. Tozer, editor of The Chicago Ledger. Through Mr. Tozer, Edwards received commissions for stories covering a period of years. The payment was $1.50 a thousand words – modest, indeed, but regular and dependable.2

From 1889 to 1893 Edwards was laboring hard – all day long at his clerical duties and then until midnight in his Fiction Factory. The pay derived from his fiction output was small, (the Ladies' World gave him $5 for a 5,000-word story published March 18, 1890, and The Yankee Blade sent him $13 on Jan. 10, 1891, for a story of 8,500 words), but Edwards was prolific, and often two or three sketches a day came through his typewriter.

Early in 1893, however, he saw that he was at the parting of the ways. He could no longer serve two masters, for the office work was suffering. He realized that he was not giving the contracting firm that faithful service and undivided energy which they had the right to expect, and it was up to him to do one line of work and one only.

"Slips and Tips"One of Mr. White's authors who had never been in Europe set out to write a story of a traveller who determined to get along without tipping. The author described his traveller's horrible plight while being shown around the Paris Bastille – which historic edifice had been razed to the ground some two centuries before the story was written! The author received a tip from Mr. White on his tipping story, a tip never to do it again.

III

METHODS THAT

MAKE OR MAR.

Edwards has no patience with those writers who think they are of a finer or different clay from the rest of mankind. Genius, however, may be forgiven many things, and the artistic temperament may be pardoned an occasional lapse from the conventional. This is advertising, albeit of a very indifferent sort, and advertising is a stepping-stone to success. The fact remains that True Genius does not brand with eccentricity the intelligence through which it expresses itself. The time has passed when long hair and a Windsor tie proclaim a man a favorite of the muses.

Edwards knows a young writer who believes himself a genius and who has, indeed, met with some wonderful successes, but he spoils an otherwise fine character by slovenliness of dress and by straining for a so-called Bohemian effect. Bohemia, of course, is merely a state of mind; its superficial area is fanciful and contracted; it is wildly unconventional, not to say immoral; and no right-thinking, right-feeling artist will drink at its sloppy tables or associate with its ribald-tongued habitues. The young writer here mentioned has been doped and shanghaied. As soon as he comes to himself he will escape to more creditable surroundings.

There is another writer of Edwards' acquaintance who, by profane and blasphemous utterance, seeks to convince the public that he has the divine fire. His language, it is true, shows "character," but not of the sort that he imagines.

A writer, to be successful, must humble himself with the lowly or walk pridefully with the great. For purposes of study he may be all things to all men, but let him see to it that he is not warped in his own self-appraisal. Never, unless he wishes to make himself ridiculous, should he build a pedestal, climb to its crest and pose. If he is worthy of a pedestal the public will see that it is properly constructed.

A writer is neither better nor worse than any other man who happens to be in trade. He is a manufacturer. After gathering his raw product, he puts it through the mill of his imagination, retorts from the mass the personal equation, refines it with a sufficient amount of commonsense and runs it into bars – of bullion, let us say. If the product is good it passes at face value and becomes a medium of exchange.

Any merchant or professional man who conducts his business with industry, taste and skill is the honorable and worthy peer of the man who writes and writes well. Every clean, conscientious calling has its artistic side and profits through the application of business principles.

Nowadays, for a writer to scribble his effusions in pale ink with a scratchy pen on both sides of a letter-sheet is not to show genius but ignorance. If he is a good manufacturer he should be proud of his product; and a good idea is doubly good if carefully clothed.

Edwards counts it a high honor that, in half a dozen editorial offices, his copy has been called "copperplate." "I always like to see one of your manuscripts come in," said Mr. White, of The Argosy. "Here's another of Edwards' stories," said Mr. Harriman of The Red Book,3 "send it to the composing room just as it is." Such a condition of affairs certainly is worth striving for.

As a rule the young writer does not give this matter of neatness of manuscript the proper attention. Is he careful to count the letters and spaces in his story title and figure to place the title in the exact middle of the page? It is not difficult.

When a line is drawn between title, writer's name and the body of the story, it is easy to set the carriage pointer on "35" and touch hyphens until you reach "45." It is easy to number the pages of a manuscript in red with a bichrome ribbon, and to put the number in the middle of the sheet. Nor is it very difficult to turn out clean copy – merely a little more industry with a rubber eraser, or perhaps the re-writing of an occasional sheet.

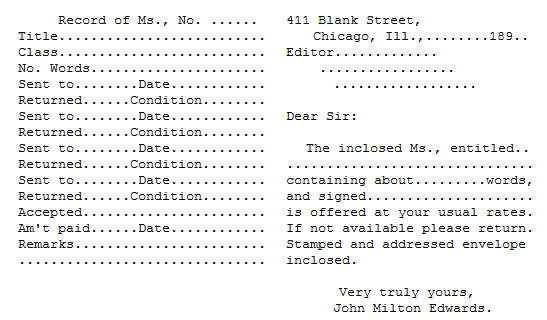

After a manuscript is written, the number of words computed, and a publication selected wherewith to try its fortunes, a record should be made. Very early in his literary career Edwards devised a scheme for keeping track of his manuscripts. He had a thousand slips printed and bound strongly into two books of 500 slips each. Each slip consisted of a stub for the record and a form letter, with perforations so that they could easily be torn apart.

Every manuscript was numbered and the numbers, running consecutively, were placed in the upper right-hand corners of the stubs. This made it easy to refer to the particular stub which held the record of a returned story.

Edwards used this form of record keeping for years. Even after he came to look upon a form letter with a manuscript as a waste of effort, he continued to use the stubs. About the year 1900 card indexes came into vogue, and now a box of cards is sufficient for keeping track of a thousand manuscripts. It is far and away more convenient than the "stub" system.

Each story has its card, and each card gives the manuscript's life history; title, when written, number of words, amount of postage required for its going and coming through the mail, when and where sent, when returned, when accepted and when paid for, together with brief notes regarding the story's vicissitudes or final good fortune. After a story is sold the card serves as a memorandum, and all these memoranda, totalled at the end of the year, form an accurate report of the writer's income.

In submitting his stories Edwards always sends the serials flat, between neatly-cut covers of tarboard girded with a pair of stout rubber bands. This makes a handy package and brings the long story to the editor's attention in a most convenient form for reading.

With double-spacing Edwards' typewriter will place 400 words on the ordinary 8-1/2 by 11 sheet. Serials of 60,000 words, covering 150 sheets, and even novelettes of half that length, travel more safely and more comfortably by express. Short stories, running up to 15 – or in rare instances, to 20 – pages are folded twice, inclosed in a stamped and self-addressed No. 9, cloth-lined envelope and this in turn slipped into a No. 10 cloth-lined envelope. Both these envelopes open at the end, which does not interfere with the typed superscription.

By always using typewriter paper and envelopes of the same weight, Edwards knows exactly how much postage a story of so many sheets will require.

In wrapping his serial stories for transportation by express, Edwards is equally careful to make them into neat bundles. For 10 cents he can secure enough light, strong wrapping paper for a dozen packages, and 25 cents will procure a ball of upholsterer's twine that will last a year.

Another helpful wrinkle, and one that makes for neatness, is an address label printed on gummed paper. Edwards' name and address appear at the top, following the word "From." Below are blank lines for name and address of the consignee.

In his twenty-two years of work in the fiction field Edwards has made certain of this, that there is not a detail in the preparation or recording or forwarding of a manuscript that can be neglected. Competition is keen. Big names, without big ideas back of them, are not so prone to carry weight. It's the stuff, itself, that counts; yet a business-like way of doing things carries a mute appeal to an editor before even a line of the manuscript has been read. It is a powerful appeal, and all on the writer's side.

Is it necessary to dwell upon the importance of a carbon copy of every story offered through the mails, or entrusted to the express companies? Edwards lost the sale of a $300 serial when an installment of the story went into a railroad wreck at Shoemaker, Kansas, and, blurred and illegible, was delivered in New York one week after another writer had written another installment to take its place. In this case the carbon copy served only as an aid in collecting $50 from the express company.

At another time, when The Woman's Home Companion was publishing a short serial by Edwards, one complete chapter was lost through some accident in the composing room. Upon receipt of a telegram, Edwards dug the carbon copy of the missing chapter out of his files, sent it on to New York, and presently received an extra $5 with the editor's compliments.

"My brow shall be garnished with bays."AMERICA

Editorial Rooms, Chicago.

Aug. 16, 1889.Dear Mr. Edwards: —

In regard to the enclosed verse, we would take pleasure in publishing it, but before doing so we beg to call your attention to the use of the word "garnish" in the last line of the first verse, and the second line of the second. The general idea of "garnish" is to decorate, or embellish. We say that a beefsteak is "garnished" with mushrooms, and so it would hardly be right to use the word in the sense of crowning a poet with a wreath of bays.

You will pardon us for calling attention to this, but you know that the most serious verse can be spoiled by just such a slip, which of course is made without its character occurring to the mind of the writer.

Yours respectfully,Slason Thompson & Co.IV

GETTING "HOOKED UP"

WITH A BIG HOUSE.

It was during the winter of 1892-3 that Edwards happened to step into the editorial office of a Chicago story paper for which he had been writing. His lucky stars were most auspiciously grouped that morning.

We shall call the editor Amos Jones. That was not his name, but it will serve.

Edwards found Jones in a very exalted frame of mind. Before him, on his desk, lay an open letter and a bundle of newspaper clippings. After greeting Edwards, Jones turned and struck the letter triumphantly with the flat of his hand.

"This," he exclaimed, "means ten thousand a year to Yours Truly!"

He was getting $50 a week as editor of the story paper, and a sudden jump from $2,600 to $10,000 a year was sufficiently unsettling to make his mood excusable. Edwards extended congratulations and was allowed to read the letter.

It was from a firm of publishers in New York City, rated up in the hundreds of thousands by the commercial agencies. These publishers, who are to figure extensively in the pages that follow, will be referred to as Harte & Perkins. They had sent the clippings to Jones, inclosed in the letter, and had requested him to use them in writing stories for a five-cent library.

Jones' enthusiasm communicated itself to Edwards. For four years the latter had been digging away, in his humble Fiction Factory, and his literary labors had brought a return averaging $25 a month. This was excellent for piecing out the office salary, but in the glow of Jones' exultation Edwards began to dream dreams.

When he left the editor's office Edwards was cogitating deeply. He had attained a little success in writing and believed that if Jones could make ten thousand a year grinding out copy for Harte & Perkins he could.

Edwards did not ask Jones to recommend him to Harte & Perkins. Jones was a good fellow, but writers are notoriously jealous of their prerogatives. After staking out a claim, the writer-man guards warily against having it "jumped." Edwards went about introducing himself to the New York firm in his own way.

At that time he had on hand a fairly well-written, but somewhat peculiar long story entitled, "The Mystery of Martha." He had tried it out again and again with various publishers only to have it returned as "well done but unavailable because of the theme." This story was submitted to Harte & Perkins. It was returned, in due course, with the following letter:

New York, March 23, 1893.Mr. John Milton Edwards,

Chicago, Ills.

Dear Sir: —

We have your favor of March the 19th together with manuscript of "The Mystery of Martha," which as it is unavailable we return to you to-day by express as you request.

We are overcrowded with material for our story paper, for which we presume you submitted this manuscript, and, indeed, we think "The Mystery of Martha" is more suitable for book publication than in any other shape.

The only field that is open with us is that of our various five and ten cent libraries. You are perhaps familiar with these, and if you have ever done anything in this line of work, we should be pleased to have you submit the printed copy of same for our examination, and if we find it suitable we think we could use some of your material in this line.

Mr. Jones, whom you refer to in your letter, is one of our regular contributors.

Yours truly,Harte & Perkins.Here was the opening! Edwards lost no time in taking advantage of it and sent the following letter:

Chicago, March 25, '93.Messrs. Harte & Perkins, Publishers,

New York City.

Gentlemen: —

I have your letter of the 23d inst. In reply would state that I have done some writing for Beadle & Adams ("Banner Weekly") although I have none of it at hand, at present, to send you. I also am a contributor to "Saturday Night," (James Elverson's paper) and have sold them a number of serial stories, receiving from them as much as $150 for 50,000 words. It is probable that material suitable to the latter periodical would be out of the question with you; still, I can write the kind of stories you desire, all I ask being the opportunity.

Inclosed please find Chapter I of "Jack o' Diamonds; or, The Cache in the Coteaux." Perhaps Western stories are bugbears with you (they are, I know, with most publishers) but there are no Indians in this one. I should like to go ahead, write this story, submit it, and let you see what I can do. I am able to turn out work in short order, if you should desire it, and feel that I can satisfy you. All I wish to know is how long you want the stories, what price is paid for them and whether there is any particular kind that you need. I have an idea that the Thrun case would afford material for a good story. At least, I think I can write you a good one with that as a foundation. Please let me hear from you.

Yours very truly,John Milton Edwards.To this Edwards received the following reply, under date of March 30:

We have your favor of March 25th together with small installment of story entitled "Jack o' Diamonds." Our careful reading of the installment leads us to believe that you write easily, and can probably do suitable work for our Ten-Cent Library, though the particular scene described in this installment is one that can be found in almost any of the old time libraries. It is a chestnut. A decided back number.

What we require for our libraries is something written up-to-date, with incidents new and original, with which the daily press is teeming. I inclose herewith a clipping headed, "Thrun Tells it All," which, used without proper names, might suggest a good plot for a story, and you could work in suitable action and incident to make a good tale.

If you will submit us such a story we shall be pleased to examine same, and if found suitable we will have a place for it at once. We pay for stories in this library $100; they should contain 40,000 words, and when issued appear under our own nom de plume.

Installment "Jack o' Diamonds" returned herewith.

Thus it was up to Edwards to go ahead and "make good." Such a climax has a weird effect on some authors. They put forth all their energy securing an order to "go ahead" and then, at the critical moment, experience an attack of stage fright, lose confidence and bolt, leaving the order unfilled.

Years later, in New York, such a case came under Edwards' observation. A young woman had besieged a certain editor for two years for a commission. When the coveted commission arrived, the young woman took to her bed, so self-conscious that she was under a doctor's care for a month. The story was never turned in.

Edwards, in his own case, did not intend to put all his eggs in one basket. He not only set to work writing a ten-cent library story (which he called "Glim Peters on His Mettle") but he also wrote and forwarded a five-cent library story entitled, "Fearless Frank." "Fearless Frank" – galloped home again bearing a request that Edwards make him over into a detective. On April 15 Edwards received the following:

We have your favor of April 13, and note that the insurance story, relating to Thrun, is nearly completed, and will be forwarded on Monday next. I hope you have not made the hero too juvenile, as this would be a serious fault. The stories in the Ten-Cent Library are not read by boys alone but usually by young men, and in no case should the hero be a kid, such as we fear would be your idea of a Chicago newsboy.

We note that you have considered our suggestions, and also that you will fix up the "Fearless Frank" manuscript with a view of making it a detective story.

For your information, therefore, we mail you under separate cover Nos. 2, 11, 15 and 20 of the Five-Cent Library, which will give you an idea of the character of this detective. We hope you will give us what we want in both these stories.

On April 25 Edwards received a long letter that delighted him. He was "making good."

I have carefully read your story, "Glim Peters on His Mettle," and, as I feared, find the same entirely too juvenile for the Ten-Cent Library, though quite suitable for the Five-Cent Library, had it not been double the length required. I first considered the question of asking you to make two stories of it for this library, but finally decided that this would be somewhat difficult and unnecessary, as we shall find a place for it later in the columns of our Boy's Story Paper, to be issued under nom de plume, and will pay you $75 for same.

The chief point of merit in the story is the excellent and taking dialogue between Glim Peters, his chum and the detectives. This boy is a strong character, well delineated and natural. The incident covered by clairvoyant visits, the scene at the World's Fair and the Chinese joint experience were all excellent; but the ghost in the old Willett house, and indeed the whole plot, is poor. Judging from this story and the previous one submitted, the plot is your weak point. In future stories make no special effort to produce an unusual plot, but stick closer to the action and incident, taken as much as possible from newspapers, which are teeming with material of this character.

We shall now expect to receive from you at an early date, the detective story, and to follow this we will forward you material, in a few days, for a Ten-Cent Library story. We forward you to-day, under separate cover, several numbers to give you an idea of the class of story that is suitable for the Ten-Cent Library. Such scenes in your last story as where Glim Peters succeeded in buying a mustang and defeated the deacon in so doing, are just the thing for the Ten-Cent Library; the same can also be said of the scene in which Meg, the girl in the bar, stands off the detectives in a vain attempt to save the villains. That is the sort of thing, and we feel that you will be able to do it when you know what we want.

I forward you, also, a copy of Ten-Cent Library No. 185, which I would like you to read, and let me know whether you could write us a number of stories for this particular series, with the same hero and the same class of incidents. If so, about how long would it take you to write 40,000 words? It is possible I may be able to start you on this series, of which we have already issued a number.

About May 1 Edwards sent the first detective story. On May 10 he received a letter, of which the following is an extract:

We are in a hurry for this series (the series for the Ten-Cent Library) but after you have finished the first one, and during the time that we are reading it, you can go ahead with the second detective story, "The Capture of Keno Clark," which, although we are in no hurry for it, we may be able to use in about six weeks or two months. You did so well with the first detective story that I have no doubt you can make the second a satisfactory one. However, if we find the series for the Ten-Cent Library O. K., we will want you to write these, one after the other as rapidly as possible until we have had enough of them.

As to our method of payment, would say that it is our custom to pay for manuscripts on Thursday following the day of issue, but, agreeably with your request, we mail you a check tomorrow in payment of "Glim Peters on His Mettle," and will always be willing to accomodate you in like manner when you find it necessary to call upon us.

So Edwards made good with the publishing firm of Harte & Perkins, and for eighteen years there have been the pleasantest of business relations between them. Courteous always in their dealings, prompt in their payments to writers, and eager always to send pages and pages of helpful letters, Harte & Perkins have grown to be the most substantial publishers in the country. Is it because of their interest in their writers? Certainly not in spite of it!

For them Edwards has written upwards of five hundred five-cent libraries, a dozen or more serials for their story paper, many serials for their boys' weekly, novelettes for their popular magazines, and a large number of short stories. For these, in the last eighteen years, they have paid him more than $35,000.

Nor, during this time, was he writing for Harte & Perkins exclusively. He had other publishers and other sources of profit.

As an instance of helpfulness that did not help, Edwards once attempted to come to the assistance of Howard Dwight Smiley. Smiley wrote his first story, and Edwards sent it on to The Argosy with a personal letter to Mr. White. Such letters, at best, can do no more than secure for an unknown writer a little more consideration than would otherwise be the case; they will not warp an editor's judgment, no matter how warmly the new writer is recommended. The story came back with a long letter of criticism and with an invitation for Smiley to try again. He tried and tried, perhaps a dozen times, and always the manuscript was returned to the patient Smiley by the no less patient editor. At last Smiley wrote a story about a tramp who became entangled with a cyclone. The "whirler," it seems, had already picked up the loose odds and ends of a farm yard, along with a churnful of butter. In order to escape from the cyclone, Smiley's tramp greased himself with the butter from the churn and slid out of the embrace of the twisting winds. "Chuck it," said Edwards; "I'm surprised at you, Smiley." Smiley did "chuck it" – but into a mail-box, addressed to Mr. White, and Mr. White "chucked" a check for $12 right back for it! Whereupon Smiley chuckled inordinately – and came no more to Edwards for advice.

V

NICKEL THRILLS AND