полная версия

полная версияBattles of English History

More important in its moral effect, more remarkable as an instance both of political and military audacity, was the reconquest of Delhi. The imperial city had but a small force of sepoys stationed in it, when the mutiny broke out at Meerut, forty miles off. Many of the mutineers hastened to Delhi, flying, it would seem, from the expected vengeance of the English troops at Meerut, who however were detained inactive by the hopeless incapacity of their general. The Delhi sepoys rose at the news, and slaughtered all the English in the city: those who lived outside fled as best they could. Lieutenant Willoughby, in charge of the great magazine, defended it for some time, aided by eight men only; and then blew it up, and a thousand rebels with it. The ancient capital, with all its resources, was for the time lost: and the mutineers proclaimed the restoration of the Mogul emperor, who, old and blind, resided in the palace, though this did not mean his assumption of any authority. The supreme importance of recovering Delhi was obvious, but it was not till three weeks after the outbreak that General Barnard, who had become commander-in-chief by the death of General Anson, marched for Delhi, ordering all that could be spared from Meerut to join him. Wilson with the Meerut force had to fight his way, and after his junction with Barnard a considerable battle had to be fought; but on June 8 the army established itself in the old garrison cantonments, on a long ridge which looks down on the city from the west and north-west. It was obviously far too small to besiege Delhi in any real sense. It could furnish visible evidence that England had not abandoned the idea of reconquest, but it could do no more without reinforcements and a siege train, unless by a direct and immediate assault. Some of the ardent spirits in the army strongly urged General Barnard to hazard an assault; and if he had done so, he might very possibly have succeeded; for the odds against him were not much greater than when Delhi was taken three months later, and the moral effect of prompt audacity is always great, especially in India. He however thought the consequences of failure too disastrous to be risked without a greater chance of success. Consequently Delhi became more and more the focus of the mutiny, to which streamed all rebels not already in organised bodies: and its fall was a greater material blow to their cause. This however can hardly be set against the value of an early proof that the British could and would re-establish their power. It requires an extraordinary man to realise that the risk of failure is no greater because the result of failure will be ruinous, and to run the risk with a full determination not to fail. Had Nicholson, or Havelock, or Edwardes, been in command before Delhi, the risk would have been faced. Barnard however was not an extraordinary man: the early opportunity once let slip, nothing could be done but hold on. The rebels, daily gaining in number and possessing unlimited stores of ammunition, made repeated attacks. The British army, though invariably successful in their encounters, and slowly gaining more and more ground, could not in any sense be said to besiege the city: they were not far from being themselves beleaguered. Moreover no help could come except from one quarter. The whole mass of the revolted territory lay between Delhi and Calcutta. The means of conquering Delhi must be furnished, if at all, from the Punjab.

England has never been better served than by the men who at the crisis of the mutiny governed the Punjab and adjoining provinces. The country was full of disaffected regiments, but they were nearly all disarmed without mischief: where material force to compel obedience was lacking, the calm assumption of irresistible authority answered nearly as well. Nowhere did the mutineers obtain the superiority, though a certain number made off towards the rebel ranks at Delhi. After a little observation of the temper of the Sikh population, Sir John Lawrence took the bold step of enlisting them by thousands, to take the place of the Mahommedan and Hindoo mutineers. The Sikhs had found the new government just: they saw its attitude of perfect confidence in its own strength, and they served it as devotedly as they had followed Runjeet Sing. Not only did Lawrence win the Sikhs to remain peaceful themselves, and keep down the elements of disorder on the borders, thus setting free the English regiments; he was able also to contribute thousands of Sikh troops of all arms to the recovery of Delhi. The delay increased his difficulties, for it weakened the belief in English invincibility. Regiments mutinied that had hitherto remained quiet: the wild tribes of the frontier, the non-Sikh parts of the population, were in a ferment. Lawrence however held firmly to his conviction that Delhi was the paramount consideration: he even despatched to Delhi the "movable column" which had been organised in the first days of the mutiny to meet emergencies. This force was commanded by John Nicholson, possibly the greatest of the many heroes of Anglo-Indian story, and he became the soul of the besieging army.

On the arrival of the siege train early in September all felt that the crisis was come. Archdale Wilson, who had succeeded to the command on Barnard's death, was still doubtful of success, but he yielded with a good grace to bolder counsels. From the nature of the case nothing could be done but to batter those portions of the walls which were within reach from the English position, and then assault. After a few days' bombardment breaches had been made in the northern walls, one in the water-bastion close to the north-eastern angle, one near the Cashmere gate, which were deemed sufficient. On September 14 the attack was made in four columns; it was not supposed that the whole of the great city, swarming with desperate men, could be conquered at once, but if a firm footing were once gained within the walls, the rest of the work might be done gradually. One column under Jones was to storm the water-bastion, another under Nicholson, the breach near the Cashmere gate: a third under Campbell was to blow in the Cashmere gate, while Reid with the fourth was to take the suburbs on the western side of the city, and make for the Lahore gate, in the middle of the western face. The two first columns advanced first, and both were successful in making good their footing within the walls. While Nicholson was fighting his way house by house onwards, Jones turning to the right made his way along the walls. It would seem as if in the confusion all parties had lost their bearings, or else Jones should apparently have taken the Cashmere gate in flank, and saved the obvious risk of blowing it in. Ultimately, Jones found himself on the west side of the city, near the Lahore gate, but did not attempt to seize it, his rendezvous with Nicholson being at the Cabul gate further north, to which he retired. This waste of a chance was not of as much importance as it might otherwise have been, for Reid's attack failed for want of guns, with which the enemy were well provided. He himself was struck down, and all his men could do was to hold firmly the extreme end of the previous position. When Nicholson at length was able to force his way to the Cabul gate, and meet Jones, the enemy was in great strength there, and it would perhaps have been better policy to be content with what had been gained on that day. Nicholson however pushed forward towards the Lahore gate, and was mortally wounded while attempting the impossible. Meanwhile the Cashmere gate had been blown in: two engineer officers, with three sergeants and a bugler, were told off for this most difficult of military duties, for it requires not merely courage to face almost certain death, but perfect coolness to deal with the unexpected. Both the officers were badly wounded, two of the sergeants were killed, the third barely escaped being crushed in the explosion, but the powder was fired, and the gate blown to pieces. Campbell had no difficulty in entering the city, but he also failed to penetrate far. The day of the storm closed with no more success than to have taken possession of the northern edge of the city, and this at a cost of 1200 men, besides Nicholson, who was worth all the rest. The first blow however was really decisive: the rest of the city had to be conquered piecemeal, but the heart of the resistance was gone. The old Mogul emperor, who had for three months been the puppet of the mutineers, was taken prisoner. His sons were shot without trial by Hodson, commander of a famous regiment of irregular cavalry, a deed for which Hodson, who acted on his own responsibility, has been very strongly condemned and as warmly defended. Terrible severity was at first employed in punishing the rebels at Delhi, for which there was the excuse that nowhere had helpless women and children been so brutally murdered. There were some who even wished to destroy the city, as an example. Thanks to Sir John Lawrence, however, humane counsels prevailed, and the peaceful inhabitants of Delhi, who had been grievously ill-treated by the mutineers, returned to their homes.

The effect of the fall of Delhi was not as great as it would have been had Barnard stormed the place in June: but it put an end to the strain in the Punjab, and followed as it soon was by the relief of Lucknow, marked the definite turn of the tide. From that time onwards it was visible to all India that the English rule would be restored. The mutineers still fought on, but in fury and despair rather than expecting success. Great as was the danger at the outset, narrow as was the margin between the English in India and total destruction, the mutiny ended in strengthening our hold in the country, besides furnishing the most vivid testimony in all history to the maxim that nothing is impossible, while life remains, to those who have courage and coolness.

APPENDIX

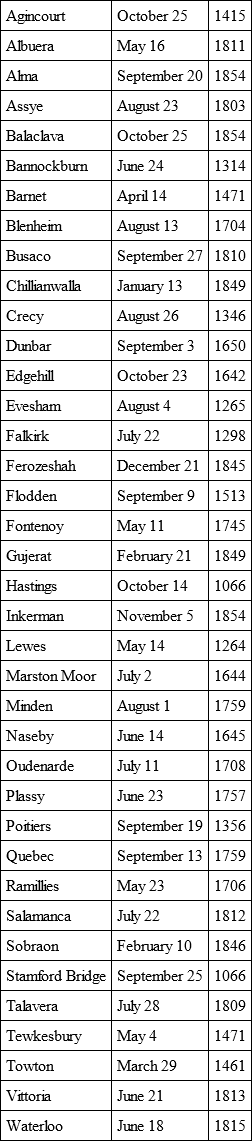

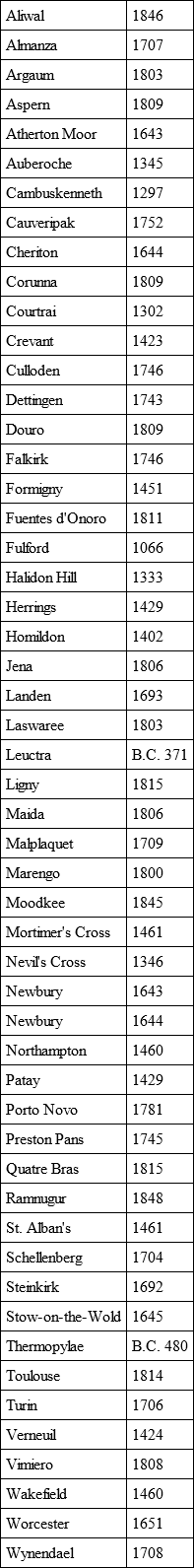

BATTLES DESCRIBED

BATTLES MENTIONED

SIEGES

1

There was doubtless learning in Northumbria, but it was altogether monastic, and limited to that one kingdom.

2

The famous story of Harold having sworn unconsciously on all the relics in Normandy, is told by the Norman writers in many different forms, more or less inconsistent with each other, and some of them demonstrably incorrect; and it is impossible to discover the truth. That William accused Harold of perjury all over Europe, and that no answer was attempted, is evidence that something of the sort had happened. As Professor Freeman points out, the absolute silence of all the English chroniclers implies that they did not know how to meet the accusation. Harold must have taken some such oath, under some form of coercion, and so have given his enemy an advantage; but obviously it would have been a greater crime to keep such an oath than to break it. Obviously too, on any version of the story that is not self-refuted, William's conduct was far more dishonourable than Harold's.

3

Professor Freeman's great History of the Norman Conquest contains a very minute discussion of every point of detail, and a narrative framed by laboriously piecing together the statements which on careful comparison he deems most correct. Much of this is very valuable, though there is at least one important point in which his account cannot be right. Much of it is more or less wasted labour, because it involves giving a precise meaning to expressions in the authorities which were probably used loosely. The main outlines are clear enough, the details are at least partially conjectural, and inferences based on physical facts are a safer guide, so far as they go, than interpretations of the inconsistent and perhaps unmeaning language of monkish writers.

There is also the Bayeux Tapestry, which has been reproduced by Mr. Collingwood Bruce, and which for costume and arms is invaluable: but from the nature of the case it is a very poor guide in determining the tactics of the battle. To rely on it for such purposes, as Professor Freeman and others do, seems to me as unreasonable as to deduce a military history of the battle of Agincourt from Shakespeare's Henry V., as put on the stage.

4

A vehement controversy has raged since Professor Freeman's death regarding the accuracy of his narrative, the point most strenuously disputed being his statement that Harold's front was protected by a solid wooden barrier. It is maintained in opposition that there was nothing but the wall of interlaced shields familiar to both Saxons and Danes. Without entering into the controversy, I content myself with saying that while the weight of testimony seems to be in favour of some kind of obstacle having been erected, I am satisfied, for the reasons given in the text, that there cannot have been anything like the massive structure described by Professor Freeman.

5

It must have been later in reality; since sunrise, the whole Norman army had marched seven miles, had halted, and had then been arrayed in order of battle, and this on October 14. Moreover, such a battle could not have lasted nine hours, and it certainly ended at dark.

6

This suggestion is not based on any direct statement, but it seems to be the only way in which the archers could have aimed effectually. If they had been behind the horsemen, shooting over their heads, the arrows would have been as likely to strike Normans as Saxons.

7

Harold's tomb was shown at Waltham down to the date of the dissolution of the abbey. There is no positive information on the point, but there seems no reason for rejecting the explanation that William afterwards allowed the corpse of Harold to be removed to Waltham. It is at least much more probable than that a falsehood should have been allowed to pass unchallenged.

8

This word, which is of course French but was adopted in English with the same signification, definitely means a body of men, originally mailed horsemen, drawn up together; but it implies nothing as to their formation or strength. The usual practice was to form three; the vanguard, which became ordinarily the right when in line of battle; the rearguard, which similarly became the left; and the main battle or centre. In the Latin chroniclers the equivalent term is generally acies, which occasionally leads to some confusion in interpreting their statements, as the classical sense of acies is order of battle, as contrasted with agmen, order of march.

9

It is suggested that this was a waggon, such as was habitually used in Italy at an earlier date, and occasionally at least in England (as at the battle of the Standard), to carry to battle the standard of the town. The earl's standard certainly floated over it, and attracted prince Edward's attention: and from the account given of the prisoners being shut up in it, it would seem to have been very substantially built. Montfort however would hardly have travelled in such a waggon, and certainly the royalists imagined he was in it. There is no reason except the silence of the chroniclers why there should not have been both a carroccio, and also Montfort's own carriage.

10

As he had not been crowned at Rome he had no right to use the imperial title.

11

The name itself may very possibly be derived from the event.

12

There are the remains of an ancient bridge at this spot, where so many of the fugitives from the battle were cut to pieces that the meadow bears the name of Dead Man's Eyot: but there is no mention of a bridge in the authorities, so that probably the bridge was built later.

13

Here again I have given the account which seems to me most probable, after study of the ground and of the authorities. Professor Prothero, in his Life of Simon de Montfort (p. 339 note), gives the different possibilities, and comes to a conclusion differing from mine on one point only.

14

Philip IV. was playing the same game, over-asserting his claims as feudal suzerain over Guienne.

15

A map showing all this part of Scotland will be found at p. 147.

16

The first victory of the pike was gained by the Flemings at Courtrai, five years later.

17

All accounts agree in representing the English numbers as more than double the Scottish, with an enormous superiority in men-at-arms, the most important item.

18

The use of the crossbow was solemnly condemned by the Lateran Council of 1139: no reasons were given, but presumably it was thought that the cross-bow neutralised the natural, and therefore divinely intended, advantage of superior strength.

19

There is a statute of Henry VIII. which forbids practising at any less distance.

20

The so-called Salic law had never been heard of till Philip V. evolved it for his own purposes a few years before: but the principle of exclusive male succession is a natural one for a feudally organised nation to adopt.

21

Louis VII. of France had it is true married the heiress of Aquitaine and ruled the province for a few years, but only in her name: and she soon repudiated him, to marry Henry II. of England.

22

This is said by Froissart to have been done on the advice of Godfrey of Harcourt, who was certainly one of the king's most trusted officers during the campaign, habitually leading the advanced guard.

23

He was in the county of Ponthieu, which had been the portion of Margaret of France, second wife of Edward I. He was not descended from her, but from Eleanor of Castile: there does not however seem to have been any provision for Ponthieu being inherited by Margaret's children.

24

Herse has another and less familiar meaning, which still better corresponds to the formation indicated – the stands used in churches for seven candles, the centre one forming the apex, and those at the sides gradually lower.

25

This theory is so far as I know novel, and I put it forward as a suggestion for what it may be worth. It explains, I venture to think, the extraordinary success of the English tactics, and it contradicts no ascertained facts. Every one who knows a little about drill will see that in this formation the archers would be able to change the direction of their shooting with perfect ease, and without interfering with each other. The archers cannot have been on the flanks of the whole line only, or their arrows, long as the range was, would not have told across the whole front. They could obviously move with ease and rapidity, and it is quite possible that they may have formed a line in front of the dismounted men-at-arms, when no attack was impending, as for instance to encounter the Genoese, and have fallen back to the herse when the knights were seen preparing to charge.

26

There is no need to insist on the picturesque detail of the rain which fell just before the battle having wetted the strings of the cross-bows, while the English kept their bows under cover. It may well have been true: but the range of the long-bow was always greater than that of the cross-bow.

27

It is convenient to use this word for those who were fighting in the English cause: but as a matter of fact two-thirds of the Black Prince's men-at-arms were from among his Gascon subjects, and the servientes therefore in about the same proportion. The archers doubtless were all, or nearly all, English: there is no trace of the long-bow except in English armies.

28

I am indebted for these details, except so far as they are from my own observation, to Colonel Babinet, a retired French officer living at Poitiers, who has published in the Bulletin des Antiquaires de l'Ouest a very elaborate memoir on the battle, which he has kindly supplemented by private letters. His study of the topography has been most minute, and his conclusions about it, so far as I can judge, are entirely sound. If there were many investigators as patient and careful, historians would find many battles less perplexing. Every one who attempts to understand the battle of Poitiers must feel grateful to Colonel Babinet, even if he does not accept all that gentleman's views as to the course of events.

29

The Chandos Herald was in the service of Sir John Chandos, one of the Black Prince's best officers. The herald was not apparently present, but he obviously must have had every means of knowing about the battle, in which Sir John fought; he did not, however, publish his rhymed narrative till some thirty years later. Froissart, who was nineteen years old in 1356, devoted his whole life to the work of his history; he was familiar with courts, if not with camps, indefatigable in acquiring information, but not critical. He too had ample opportunities of learning all about the battle of Poitiers, at any rate from the English side. The manuscripts of Froissart, however, vary greatly, which casts a certain doubt over the trustworthiness of such details as are not given identically in all. Baker was a clerk of Swinbrook in Oxfordshire: the last words of his chronicle were written before the peace of Bretigny in 1360, so that he was even more strictly contemporary than Froissart. Several passages in his history, in which he makes very definite statements about the tactics of the long-bow, prove that he, or his informant, understood military matters well. None of them can have seen the ground, and therefore no stress need be laid on minor inaccuracies of description. Mistakes about the names of actors in the drama might easily be made: all that can be said is that the writer who has made fewest errors has a slightly better claim to general credibility. None of them can be deemed likely to have deliberately misrepresented, or to have been totally misinformed about the ground-work of the whole story. Yet there is the fact, that their narratives are substantially contradictory. Critical ingenuity may no doubt patch up some sort of superficial reconciliation between them, but it can only be superficial. Under these conditions I have no alternative but to follow the narrative which seems to be most in accordance with the known facts. I am not ignorant of the difficulties involved in this course, but my plan does not admit of a full discussion of every point that might be raised. On the whole I incline to discard the Chandos Herald, the more so because none of the less detailed narratives support him, and as between Froissart and Baker, to prefer the latter. My account of the actual battle will therefore follow the chronicle of Baker of Swinbrook, in all matters in which he and Froissart are completely at variance.

30

According to Baker, the prince began this movement cum cariagiis, to which, however, there is no further reference. It is obviously possible that the prince may have wished to get the baggage out of the way, and therefore started it towards the Gué de l'Homme, and that he shifted his troops in order to cover this from the French. If so, this would be the element of truth in the Chandos Herald's narrative; but it does not in any way remove the essential contradiction between the Chandos Herald and the other authorities.

31

Froissart calls him Thomas lord of Berkeley, a young man in his first battle, and says he was son of Sir Maurice Berkeley, who died at Calais a few years before. Thomas the then lord of Berkeley, and elder brother of that Sir Maurice, was in the battle, but he was a man of over fifty, and he had his son Maurice with him for his first campaign. That Baker should be right, and Froissart wrong, on a point peculiarly within Froissart's province, is a striking incidental testimony to Baker's trustworthiness.