Полная версия

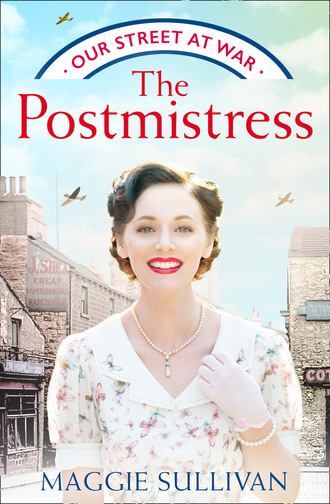

The Postmistress

‘You, my girl, are doing your duty. Nothing more, nothing less, and don’t you ever forget it.’

Vicky’s shoulders slumped for she knew he was right and there was little point in denying it. Life had not been easy for any of them. ‘You know, Dad, I’ve never objected to doing my duty as you call it, it’s just that …’ As she clenched and unclenched her fists, Vicky suddenly realised that this was a fight she had been spoiling for ever since she had been hauled out of school at the age of fourteen and told that, as Dot was now leaving to get married, it was her job to look after her little brother. She had so desperately wanted to continue her education, to stay on at school and perhaps go to secretarial college. But she hadn’t felt able to argue then and she didn’t feel able to say anything now. Not when she had been guilty of contributing to the family’s misfortunes. All she could do was to try her best to make amends. ‘You must know I do my best to do my job and to look after you and the house and … whatever else is needed,’ she said, ‘but I don’t see why—’

‘It was hardly my fault that I came back from the war like this, I can bloody assure you of that!’ Arthur cut in, wheezing heavily, though he still managed to carry on talking. ‘Any more than it was anyone’s fault that your poor mother caught that damned Spanish flu right at the end, even though she’d managed to see out the war. But what was your bloody fault was … was …’

Vicky could see that he was struggling to get the words out now, but as he spoke Arthur stood up and to her astonishment began fumbling with his belt. Fortunately, he didn’t have the strength to disengage the buckle before he fell back onto the couch, overcome by a terrible coughing spasm. As far back as she could remember, her father’s physical strength had not been able to match his temper, though he could still hurt her with his tongue lashings. But for once her tears were frozen. She didn’t need reminding of what she had done.

‘It’s no less than you deserve when I think of the shame you were on the verge of bringing onto this family!’ Arthur shouted at her. ‘You’re no better than you should be.’

‘That was three years ago,’ Vicky said softly. ‘But you certainly make sure I keep paying for it, don’t you? While all the time your precious Henry gets away with murder. When are you going to face up to him and tell him to start pulling his weight?’ As she said this, her father began to cough again and this time she was afraid he wouldn’t be able to stop. She became really scared as his eyes began to bulge and it took all her strength to prop him up on the couch and loosen his collar. She ran into the scullery for a cold compress and tried to dab it on his forehead, but he shrugged her away.

‘I should have thrown you out when I had the chance. You and your wanton ways,’ Arthur gasped between wheezes. ‘I swear to God, you’ll be the death of me. But maybe that’s what you want?’ Without warning he pushed Vicky’s hand away. He swung his legs round and stood up unsteadily, lurching in the direction of the stairs. ‘Call me when my dinner’s ready,’ he said and heaved himself upwards one step at a time.

Vicky could feel her eyes burning but she was determined not to let her father see her cry. She had a problem. Arthur’s breathing seemed to be getting worse. Maybe she should ask Dr Buckley to come and have a look at him, find out if there was anything else he could do. She would even pay him, if necessary, if an extra visit wasn’t covered by Arthur’s GPO Health Insurance scheme. Roger Buckley seemed to be the only person her father really trusted, the only one apart from her and Henry that he would allow inside the house.

She sat at the table for a few minutes, rubbing her eyes with the heels of her hands. She could only feel sorry for what her father had suffered as a direct result of being so badly gassed during the Great War. But on a practical level, the remnants of his injuries put a great strain on her and now she feared that the symptoms were escalating. Today was the first time Arthur had refused to come to help out in the Post Office – and if he wasn’t able to work behind the counter, then she would need to look for some help. It was a full-time job and she could no longer cope with it while at the same time having to be housekeeper, shopper and general factotum as well, no matter what she felt was her duty. And what would she do when Arthur needed more nursing? How would she manage then? Whether she would be able to carry on looking after him if his health continued to deteriorate at the rate it had recently was a question for Dr Buckley.

Perhaps she should contact her bosses at the GPO and sound them out about getting an assistant? Unless, of course, she could ask Henry. Maybe she should approach her brother and try to make him see how much she would appreciate his help, urge him to at least shoulder some of the responsibility.

The trouble was that as the threat of war became more immediate, so more people wanted to stop and chat about it. She hated being rude to her customers, but it was becoming almost impossible for Vicky to encourage them to pay for their purchases and be on their way. She was named as the postmistress, although the certificate of trading was in Arthur’s name, but she could hardly spell out to her customers, most of whom she had got to know well over the years, that she needed time to be able to see to all her other chores as well. It was even becoming difficult to lock the door for an hour at midday as she was entitled to do because there always seemed to be someone who had something important that needed to be dealt with immediately. She could understand if it involved sending an urgent telegram but it rarely did, so why buying a postage stamp or writing paper and envelopes couldn’t wait for an hour Vicky was unable to understand; she only knew she felt as if she was being pulled in all directions …

Henry came in later than usual that night, through the back door they used as their personal home entrance, and he ran straight up the stairs to the room he shared with his father, ignoring Vicky’s greeting and her enquiry regarding his tea.

‘Where’s Dad?’ he called down over the bannisters.

‘Down the garden,’ Vicky said, invoking the euphemism the family used to describe a visit to the lav.

‘Damn, I need him to be here.’ Henry came down the steep stairs slowly. He sat on one of the chairs at the table and hid his face behind the sports page of the evening paper he’d brought in with him. Then he jumped up and paced back and forth in the small living room.

‘Why don’t you go and wash your hands and I can serve up your tea?’ Vicky said. ‘It’s better than you wearing out the carpet. We don’t have to wait for Dad.’ She was wondering if she might be able to pin Henry down before their father returned, talk to him about taking more responsibility for looking after Arthur.

‘I’m not ready to eat yet,’ Henry said ‘I’ll hang on till Dad gets here. I’ve got summat to tell you both and I’m not saying it twice.’

‘I thought you were looking agitated. What’s wrong?’ Vicky asked, as he circled the table for the third time. Her brother’s restlessness seemed to fill the room and she was beginning to feel the waves of his anxiety wash over her.

Thankfully, it was not for long. Henry had sat down and stood up again several more times when, to the relief of them both, there were the distinctive sounds of Arthur making his way down the path and through the backyard. Vicky saw it as her cue to bring in the large earthenware dish from the oven and begin ladling out the steaming juicy layers of spicy meat, potatoes and vegetables that comprised her own special version of hotpot that she knew they both loved. She brought in three large bowls from the scullery and began to fill them before placing them on the wooden mats she had laid on the table.

‘Hurry up, Dad,’ she called out. ‘Yer tea’s ready. It’s yer favourite and I’m just serving up.’

Arthur ran his hands briefly under the cold water tap, then he rubbed them down the front of his heavy drill trousers in an attempt to dry them.

‘We’ve been waiting for you because Henry’s got something to tell us,’ Vicky said.

‘Oh, and what’s that?’ Arthur asked as he sat down. He turned to face Henry, but as he did so his face seemed to drain of blood. It was then that Vicky gasped, covering her mouth with her hands and looking from one to the other as she suddenly realised from reading her father’s face what it was her brother had come to tell them.

For a moment nobody spoke. Vicky automatically handed round three sets of forks and spoons but no one attempted to eat from their fast-cooling plates. Henry picked a corner off one of the slices of bread that had been piled onto a plate in the centre of the table and almost unconsciously began to roll small fragments between his index finger and thumb. Then he nervously gathered the tiny grey pellets into a cairn-like pile beside his plate on the oilcloth. He didn’t look at her or his father as he spoke.

‘I’m going to join up. Sign on for the army. I thought you ought to know,’ he said eventually.

The silence that followed was broken only by the sound of Arthur wheezing. His brows knitted then his lips twitched into an uncertain smile. Henry looked up at that moment, his eyebrows raised in query as his gaze met Vicky’s but for once she didn’t know what to say.

‘Look …’ Henry filled the void when neither Arthur nor Vicky spoke. ‘There’s no question about whether this war’s going to happen. I’ve no doubt in my mind that it will, and it will be soon. Meaning that it will be over soon, but the thing is … I want to be part of it. I want to be there to stick it to the Germans, so that we can shut them up for ever. I say we need to show them who’s boss, get it over and done with before they’ve got a chance to invade any other countries … And that might include Britain. Whichever way, my bet is that war will be declared sooner rather than later.’

‘But—’ Arthur started to say but Henry cut him off.

‘No, Dad, I don’t think there are any buts. It won’t be like last time. This time it really will all be over by Christmas. Hitler’s off his rocker, thinking he can take on the world, and I say that the more of us join up early, the easier it will be to show him that he can’t.’

‘When will you …?’ Vicky’s voice croaked as she struggled to control it.

‘Not sure yet, but it will be soon.’

For the moment she forgot the speech with which she had been preparing to confront Henry. Now all she could do was fear for the life of her little brother and worry about how she and Arthur would manage with him gone.

‘What about your job?’ Vicky managed to say eventually as it dawned on her that they would be down to a single wage coming into the household. But Henry was not thinking along the same lines.

‘What about it? I hate the bloody foundry,’ he said vehemently. ‘I’d have left no matter what. In fact, I’ve already handed in my notice so there’ll be no delay in me actually signing on the dotted line.’

‘You mean you …?’ Vicky said.

‘I’ll be volunteering, yes. I don’t imagine I’ll have any problem passing a medical so I’m not waiting for any kind of forced conscription, if that’s what you’re thinking. I’m taking fate into my own hands and doing summat useful for my country at the same time.’

He beamed as he spouted what Vicky knew to be the message on some of the recruitment posters she’d seen pasted up around the town. She felt a cold shiver that was more like an electric charge shoot down her spine. ‘You mean you can’t wait to get away. To leave us here to our own devices?’ she finally managed to say.

Henry looked puzzled. ‘What do you mean? You’re capable of managing perfectly well on your own. You don’t need me.’

Vicky wondered if there would have been a different outcome if she had managed to get her two penn’orth in first before he’d made his announcement. What would have happened if she’d had a chance to tell him of her fears and concerns? Would she have made him change his mind? She had to admit that she doubted it but she asked the question anyway. Turning to face Henry and using as quiet a voice as possible she said, ‘And how am I to cope if Dad gets really sick? I do worry about him, you know.’

Arthur had picked up his empty pipe from the table and was pulling hard on the stem as if it were lit. ‘You don’t have to worry about me, girl. I shan’t be any bother,’ he said quickly as if to show her he’d heard her whispered words. ‘Of course he must go and fight for his King and country,’ he said with a satisfied smirk.

‘How can you say that? Look where fighting for your country got you.’ Her voice was twisted in a sob. ‘And where did fighting get my poor Stan?’ Vicky stopped, angry that she couldn’t disguise her voice breaking. ‘And I didn’t notice the King or your country stepping in to do much once you were wounded.’

‘I was unfortunate. But Henry’s got a chance to be the hero I never was,’ Arthur said, a broad smile on his face now.

Henry blushed but didn’t respond.

‘And you and me will manage, lass, you wait and see.’ Arthur patted Vicky’s leg under the table.

Vicky screwed up her eyes tight but to her chagrin scalding tears still managed to make serious tracks down her cheeks.

‘So once again it’s me that’s left with all the responsibility, me that will have no choice, no life.’ She thought she had whispered the words so that only she could hear them but Arthur’s response was swift and cruel when he gave a scornful laugh.

‘You’ve not shown any interest in having a life for the past however many years, so why suddenly the concern now? You don’t even respond when someone does take an interest in you.’

Vicky looked puzzled but her father didn’t elaborate. Instead, he went on, ‘And once upon a time you were prepared to throw your life away completely for a fella – and you would have too, if the war hadn’t stopped him in his tracks.’ Vicky could feel the colour rising from her neck to her cheeks and up to the top of her head as she glared at her father.

‘All I can say is, I’m glad you’re not thinking of doing that now, sis,’ Henry suddenly said and he reached across the table and squeezed her hand. ‘We’ll be needing the likes of you to keep the home fires burning and all that. Isn’t that what they used to sing about in the Great War, Dad?’

‘They did indeed,’ Arthur said and he began to hum the first line of the well-known song. ‘Besides, you should be thankful your life’s turned out so well, given the kind of start you had. There’s lots of girls would give their eye teeth to have what you’ve got right now: a good job, a home, a family.’

Vicky could only stare at him, her thoughts momentarily bound up with all that she had lost, though she switched her gaze as Henry stood up and pushed his chair back.

‘Well, I’m off to tell my mates.’ He grinned. ‘See if I can shame them into joining me. I’ve got a feeling I might be the first, but I know I certainly won’t be the last.’

Arthur slowly got up from the table. He went over to Henry and patted him on the shoulder. ‘I’m proud of you, son,’ he said. ‘I’m sure you’re doing the right thing.’ Then he turned to glower for a moment at Vicky. Unexpectedly, she shuddered. It was the kind of look that had frightened her when she was a little girl, when her father had just come back from the war, just after her mother had died. And it frightened her now to think that in her father’s eyes she would probably always be second best. As if to underline the sentiment, Arthur turned his attention back to Henry and beamed at his son one more time.

‘You don’t worry about us, lad,’ he said. ‘You go and do what you’ve got to do.’ And he patted him one more time on the back, ‘We’ll manage, same as we always have.’ And with that he slowly made his way up the stairs.

Chapter 2

‘Daddy! Daddy!’ The little girl squealed with joy as she ran across the hall and into her father’s arms. Roger Buckley put down his doctor’s Gladstone bag that suddenly felt heavy and he opened his arms wide to accommodate the sturdy six-year-old.

‘Julie, my love. What a wonderful welcome, as ever,’ he said. He kissed the top of her head and stroked her gleaming black hair that hung straight to her shoulders. It was smooth and sleek just like her mother’s had been. Such moments always brought a tear to his eyes.

‘Don’t touch my hair, you’ll mess it up,’ Julie said, patting it down with her hands.

Roger didn’t mind that his daughter was unusually vain for her age about her hair. He found it strangely comforting. He loved to see her comparing it with the well-thumbed photos of Anna that, at Julie’s insistence, adorned her bedroom. If she deemed it to be so much as an inch longer than the hair in the photographs, she insisted that her granny cut it.

At that moment Freda Buckley appeared and, as she opened the door from the family’s living quarters that led into the hall, Roger was greeted by the appetising smell that suggested his mother’s indulgence of his favourite – cottage pie.

‘Roger, darling.’ She greeted him warmly. ‘You’re later than usual. I nearly sent your father on a trek to the surgery to make sure you hadn’t got lost coming from there to here.’ She grinned but Roger only shrugged, too tired even to laugh at the well-worn family joke, the clinic where he worked most afternoons being attached to the other side of the house.

‘You know how it is,’ he said. ‘There’s always someone likes to arrive just as I’m about to close up for the night. It’s as if they can’t bear to let me go home.’ Then he smiled. ‘Though I must admit it has been busier than usual today. I think people are gearing themselves up to the fact that there really will be a war and they want to get any niggles sorted out while things are still running relatively normally. I suppose it won’t do them any harm to be in as good a condition as possible if we’re going to be hit by rationing and food shortages.’

‘You might be right. But you should be more assertive.’ Freda playfully wagged her finger at him. ‘Meanwhile, your dinner awaits. Julie’s already had her tea but your father and I haven’t eaten yet; we thought we’d wait for you, though we had almost given up on you.’

‘But I want you to read me a story first!’ Julie tugged at his arm. ‘I’ve been waiting soooo long.’ She sighed in such a grown-up way that it made Roger smile.

‘All right, I’ll read you a story.’ He bent down and kissed her forehead. ‘Though only one. No nagging for another one.’

‘I promise.’ Julie momentarily put her thumb in her mouth and quickly turned away before she could be admonished.

‘But while I take off my things why don’t you tell me all about your day at school,’ Roger said.

Julie let go of his hand and ran through the short corridor that led into the kitchen while he hung up his coat on the hall stand and took off his jacket. She skipped back into the hall waving a piece of sugar paper that had been carefully folded so that it looked as if it had wings, and he could see it had been decorated with patches of pastel-coloured tissue paper that had been stuck all over it.

‘Miss Pegg said it was really good and she pinned it up on the achievements board for the afternoon.’ She made the word ‘achievements’ sound more like a sneeze and the doctor laughed. ‘And I got a star on my work chart,’ Julie said, refusing to be put off.

‘That’s very clever of you,’ her grandmother intervened. ‘And now I think you should go up to bed and Daddy will come and read to you shortly.’

‘Oh, can’t I stay up a little bit longer?’ Julie begged.

‘You heard what Grandma said,’ Roger said. ‘I’m very tired and I need to have something to eat, but I’ll put you to bed first with one story, as I said. And if you’re really good and go to sleep then, like you promised, then we can go fishing in the park, maybe even this weekend so long as it doesn’t rain.

‘Ooh, goodee!’ Julie clapped her hands with delight as she started up the stairs.

‘But haven’t you forgotten something?’

‘Oops!’ Julie said and she ran quickly back into the kitchen where Roger heard the sound of a sloppy kiss.

‘Night-night, Grandad,’ she called and within seconds she was back in the hall where the sound of the kiss was repeated. ‘Night-night, Grandma,’ she said. ‘Come on, Daddy.’ She pulled on his hand. ‘Come and read Mr Galliano’s Circus to me.’ She put on an imitation of an adult voice, ‘The sooner we start, the sooner you can eat. Isn’t that what you always say?’

Roger couldn’t help laughing at that. ‘It is indeed.’ He ruffled her hair. ‘Now come on, my precocious little child, or Grandma will be chasing after the both of us.’

He didn’t even get to the end of the chapter before he heard Julie breathing deeply and he crept downstairs so as not to disturb her. His father poured two fingers of whisky into a crystal glass and pushed it towards him almost the moment he appeared, and his mother began serving up the appetising dish of well-seasoned meat topped with creamy potatoes as if she had been standing, ladle poised, waiting for him to appear. But on cue, as they were ready to begin eating, they were assailed by a loud wail from upstairs followed by, ‘Where’s my water? I want a glass of water.’

Roger half rose but his mother patted his arm. ‘You stay and eat; I’ll see to her.’ And Roger didn’t protest.

‘I’ll be back in a moment, Cyril,’ she said to her husband as she poured a tumbler full of water ready to take upstairs.

‘Long day?’ his father said when Freda had left the room. Roger nodded. ‘I remember them well,’ Cyril said smiling. ‘And I can tell you, long hours are not something I miss.’

Roger took a sip from his whisky glass then sat back. ‘Oh dear,’ he said. ‘That sounds ominous.’

‘Oh dear? What’s that supposed to mean?’ Cyril said.

‘It means I was hoping you were going to say something else. Does a tiny part of you really not sometimes hanker to come out of retirement and go back to work for a little while? Just to keep your hand in?’

The older man exploded into a blustering laugh. ‘Good heavens, no! Why should I want to do that?’ He picked up his whisky glass but he put it down again before it reached his lips and he gave Roger a quizzical look. ‘You’re serious? Come on, spit it out, old chap.’

‘Unfortunate choice of phrase, Dad.’ Roger gave a humourless laugh.

‘Are you really saying what I think you’re saying?’ Cyril said, his brow creasing with a frown.

‘Yes, I think I am,’ Roger admitted. ‘You must have seen the recruitment posters? They’re all over the place.’

‘And you’re thinking … what, exactly?’

‘I’m thinking that, as a medic, I could make a damned useful contribution.’

Cyril frowned, looking worried for a moment, but then he sat back with a look of genuine relief. ‘But they won’t want you, Roger. You’re too old.’ He hesitated. ‘Aren’t you? You won’t have to go into the forces, surely?’

‘Not immediately, no. But once this thing gets going, how long do you think it will be before they widen the parameters?’

‘What? Do you mean extend the age groups?’

‘That and the fact that they’ll want trained doctors, not just medics or nurses.’

‘You really think it’s going to happen?’

‘Without a shadow of a doubt, I’m afraid. If you listen to the news it sounds inevitable.’

‘Hmm.’ The older man nodded. ‘You’re probably right. So you’d rather pre-empt a compulsory call-up and volunteer?’

‘I thought that if I did it might give me the edge, a little leverage, a bit more choice about where I end up.’

‘Who knows what’s going to happen? Who knows?’ Cyril looked pensive but didn’t ask any more questions and nothing further was said about it when Freda came back to join them.

They finished their meal without further conversation, the only sounds in the room being the genteel tapping of the highly polished silver-plated cutlery on the fine china plates. Then Roger helped his mother pile the dirty dishes into the sink in the kitchen and left her to deal with them while he poured another splash of whisky for himself and Cyril. He sat at an angle next to his father so they both faced the hand-embroidered fireguard that hid the empty fireplace and he pulled a small table into place between them. He refused the offer of a cigar but leaned across the table to grasp hold of the table lighter to light one for Cyril.