полная версия

полная версияA History of Sarawak under Its Two White Rajahs 1839-1908

We have little more of public interest to record concerning the history of the Raj and the lives of its Rajahs. The commercial and industrial progress is dealt with in a later chapter, and that will show the gradual development of the country to its present prosperous condition, and the achievement of an unique undertaking which has been carried into effect slowly, but surely and with determination.

We quote the following extract from Consul Keyser's report to the Foreign Office for 1899: —

This country (Sarawak) makes no sensational advances in its progress. Reference to statistics, however, will prove that this progress is sure, if slow, and each year adds money to the Treasury in addition to the main work of extending a civilisation so gradual that it comes without friction to the people. It is because the ruler of the country regards his position as a trust held by him for the benefit of the inhabitants that this progresses necessarily slow, since sudden jumps from the methods of the past to the up-to-dateism of modern ideas, though advantageous to the pocket, and on paper attractive, are not always conductive to the happiness of the people when peremptorily translated. Yet all the time good work is being quietly done. Improvements are made and commerce pushed, wherever possible, without fuss or the elements of speculation.

The prosperity of the country has not been built up out of the great natural riches of a State such as that of the Malayan peninsula, backed by Imperial support, nor with the aid of the capital and credit of a chartered company, but has followed in the train of a hard and single-handed struggle to convert a desolated country into one happy and contented, and it has succeeded so far as to place Sarawak foremost amongst the Bornean States in commercial wealth.

We have shown how this has been achieved, and "if it is owing to Sir James Brooke that Sarawak is now a civilised state, his nephew, the present Rajah, has the high merit of having completed and extended that work, following out the humane and liberal views of his uncle. The name of Brooke will always have an honoured place in the history of the development of civilisation in the Far East."352

We will give in the Rajah's own words his views as to the form of government best adapted to the nature and requirements of an oriental people, written in 1901: —

To keep such people in order a just and impartial rule, in which both rulers and ruled alike do their portion of work, is required. Like all Easterns they need a government simply formed and tutored by experience gained in the country itself, experienced in the manners and methods of the people, devoted to their welfare and interests, an indigenous product of the country which it governs, untroubled by agents or officials sent from outside, who, partly owing to want of reciprocal feeling and sympathy with the people, partly through ignorance, and partly through adherence to impracticable laws are liable to make such fatal mistakes in their dealings with Easterns which naturally leads to discontent, and even to rebellion.

The success this policy has met with is borne out by the testimony of Sir W. Gifford Palgrave, the Arabian scholar and traveller, and Mr. Alleyne Ireland, as well as by that of many others whom we have already quoted.

The former, when British Minister at Bangkok, visited Sarawak in 1882, and subsequently wrote to the Rajah: —

It is a pleasure to me to think that I shall be able to bear personal witness, when in England, to the success of your administration, which by its justice, firmness and prudence seems to me to work up better towards that almost utopian climax of "the greatest happiness to the greatest numbers" than any Eastern government (white or brown) that I have yet seen.

Mr. Alleyne Ireland was sent out from the United States by the University of Chicago to study British and other Tropical Colonies and to report thereon. A preliminary report was published in 1905, under the title of The Far Eastern Tropics. After commenting severely on the mistaken methods adopted in the Philippines by the U.S.A., he turned to Sarawak, where a method in all points the reverse had been steadily pursued under the two Rajahs. This is what he says: —

For the last two months (written in January 1903) I have been in Sarawak, travelling up and down the coast, and into the interior, and working in Kuching, the capital. At the end of it, I find myself unable to express the high opinion I have formed of the administration of the country without a fear that I shall lay myself open to the charge of exaggeration. With such knowledge of administrative systems in the tropics as may be gained by actual observation in almost every part of the British Empire, except the African Colonies, I can say that in no country which I have ever visited are there to be observed so many signs of a wide and generous rule, such abundant indications of good government as are to be seen on every hand in Sarawak.

And again: —

The impression of the country which I carry away with me is that of a land full of contentment and prosperity, a land in which neither the native nor the white man has pushed his views of life to the logical conclusion, but where each has been willing to yield to the other something of his extreme convictions. There has been here a tacit understanding on both sides that those qualities which alone can insure the permanence of good government in the State are to be found in the White Man and not in the Native; and the final control remains therefore in European hands, although every opportunity is taken of consulting the natives and of benefiting by their intimate knowledge of the country and its people.

The wise and essential policy of granting the natives through their chiefs a part in the administration of the Government and in its deliberations, and in the selection of these chiefs of regarding the voice of the people, has always been maintained. Sympathy between the ruled and the rulers has been the guiding feature of the Rajah's policy, and this has led to the singular smoothness with which the wheels of the Government run. It must always exist, as it has ever existed, and still exists. That the country belongs to the natives must never be forgotten, and the people on their part will never forget that they owe their independence solely through the single-hearted endeavours of their white Rajahs on their behalf.

"The real strength of the Government," writes the Rajah, "lies in the native element, and depends upon it, though many Europeans may hold different views, especially those with a limited experience of the East. The unbiased native opinion, Malay and Dayak, concerning matters relating to the country is simply invaluable."

All with a true knowledge of natives, to whom his remarks may be said to apply generally, as well as to the Malays, will agree with Sir Frank Swettenham: —

That when you take the Malay, Sultan, Haji, chief, or simple village headman into your confidence, when you consult him on all questions affecting his country, you can carry him with you, secure his keen interest and co-operation, and he will travel quite as fast as is expedient along the path of progress. If, however, he is neglected and ignored, he will resent treatment to which he is not accustomed, and which he is conscious is undeserved. If such a mistake were ever made (and the Malay is not a person who is always asserting himself, airing grievances, and clamouring for rights) it would be found that the administration had gone too fast, had left the Malay behind, left him discontented, perhaps offended, and that would mean trouble and many years of effort to set matters right again.353

Sir Frank Swettenham pays a high tribute to the Malays of rank of the Malay Peninsula, quite as justly have those of Sarawak earned the same praise. Foremost amongst these latter stood the old Datu Patinggi Ali, the champion of his people's cause, before the deliverer from oppression came in the person of the late Rajah, in whose service he gallantly sacrificed his life. Of a different type was his eldest son, the Datu Bandar Muhammad Lana, whose courage was masked by a gentle and retiring disposition, though it flashed forth on many occasions, notably at the time of the Chinese rebellion. His brother, who succeeded him on his death, the late Datu Bandar Haji Bua Hasan, previously the Datu Imaum, was one of the most trustworthy and faithful chiefs the Government has had. By his long and faithful service of over fifty years he had won the most honoured place amongst those chiefs who so nobly assisted the two Rajahs in their work in laying the foundation of law, order, and civilisation in Sarawak. He was held in esteem and respect by all people, and his dignified and familiar figure is greatly missed. He died on October 6, 1906, over one hundred years of age, another example of longevity of life amongst Malays. As his descendants number exactly one hundred and fifty, the continuity of old Rajah Jarom's line is ensured. Two of his sons, Muhammad Kasim and Muhammad Ali, are now respectively the Datu Bandar and the Datu Hakim. The third son of Datu Patinggi Ali, Haji Muhammad Aim, became the Datu Imaum in 1877. He died in 1898, justly loved by all for his kindly nature and strict probity; no truer or more courteous gentleman could be found.

Of another family and of a very different type was the bluff old Datu Temanggong Mersal, with the reputation of having been a pirate in the bad old days, but who had "a fine spirit of chivalry which made up for a hundred faults."354 He was a stout and staunch servant. Of him the late Rajah, referring to the Datu's Court, humorously wrote: —

The old Temanggong is likewise a judge in Israel, and sometimes he breaks into the Court, upsets the gravity of all present by laying down his law for a quarter of an hour – Krising and hanging, flogging and fining all offenders, past, present or future, and after creating a strong impression vanishes for a month or two.

Absolutely fearless as himself were his sons Abang Pata and Muhammad Hasan. How the former distinguished himself we have already noticed. On the death of his father in 1863 the latter succeeded him as Datu Temanggong. He was a tall, handsome man of a distinct Arab type. Though a good Muhammadan, he was the least bigoted of a broad-minded class, and owing to his liking for their society he was probably the most popular with Europeans of all the datus, and at their club he was a constant and welcome guest. He died on the haj at Mecca in October, 1883.

Other native officials, whose names will ever live in the annals of Sarawak, are some who served in the out-stations, and these have been already noticed. The qualities which distinguished these men, and which brought them to the fore, were grit, sound common-sense and fearlessness, and upon their shoulders fell the hardest task of managing the Sea-Dayaks and other interior tribes, a task fraught with danger and discomfort, and one that gave them little rest, but which they shared with their white leaders faithfully and without a murmur.

Sarawak has been exceptionally fortunate in having been able to draw upon a good class of men capable of supplying the State with servants fitted by intelligence and rank to become native officers. Though, autre temps, autre mœurs, the type is changing, yet the people generally are jealous of their country, and honour its traditions. Contented, they seek no change, and they are ready to uphold their Rajah and to maintain their independence as vigorously now as they have done in the past – an independence which Lord John Russell had many years ago graciously intimated they were at liberty to achieve and maintain as far as it lay in their power; though he declined to hold out a helping hand. These are wholesome and promising indications that good men will always be found worthy to take the places which their forefathers so nobly filled.

Sarawak owes its prosperity, and the people their rights and liberty, to the Brookes, and to the Brookes alone. Equality between high and low, rich and poor, undisturbed rights over property, freedom from the bonds of slavery and from harsh and cruel laws are blessings which but for the Brookes in all probability would have been denied them for many more weary years of desolating tyranny.

In a country like Sarawak, peopled by Easterns of so great a diversity of races, customs and ideas, an union of the people for their common weal is an impossibility. For them the best and only practical form of government is that which they now enjoy, a mild and benevolent despotism, under a Ruler of a superior and exotic race, standing firm and isolated amidst racial jealousies, as no native Ruler could do, and unsuspected of racial partiality; a Ruler upon whom all can depend as a common friend, and a Ruler who has devoted his life to their common welfare.

Strength of character and integrity of purpose, tact and courage, firmness and compassion, combined with a thorough knowledge, not only of their languages and customs, but of the innermost thoughts of his people, to be gained only by a long experience, are qualities without which a despotic Ruler must fall into the hands of the strongest faction, and, eventually bring disaster on himself and his country; but are those which have enabled the Rajah to tide over many political troubles, to consolidate the many and diverse interests of his people, and to guide the State to its present position of prosperity and content.

CHAPTER XVI

FINANCE – TRADE – INDUSTRIES

A general review of the financial, commercial, and industrial progress of Sarawak will probably convey to our readers a better conception than the foregoing history may have enabled them to form of the uniform advance of Sarawak along the path of civilisation: for no better evidence of the prosperity of a country can be advanced than the growth of its trade and industries, dependent as this is upon security to life and property and liberal laws.

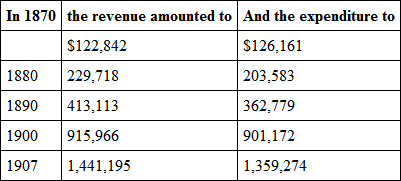

Of the revenue before the Chinese rebellion there are no records, as all the archives were then destroyed. Three years later, in 1860, the revenue was so insignificant as to be quite inadequate to meet the needs of the country, which then for the first time became involved in debt; a debt which was unavoidably increased in subsequent years, until it had reached a somewhat high figure for such a young and striving State, but from which, however, it has now been freed by the exercise of prudent economy, and by improvement in its finances.355

On January 1st, 1908, the Government balances amounted to a little over $800,000, and the only liability was for notes in circulation, amounting to $190,796.

In 1875, fifty-six years after its foundation, the revenue of Singapore was but $967,235, and that of Penang, then established for eighty-nine years, $453,029.356 In 1900, the Raj of Sarawak had been in existence for fifty-eight years. Since 1875, the effect of the development of the rich tin deposits of the Malayan States of the Peninsula has been to so enormously enhance the commercial prosperity of the Straits Settlements that the present revenues of the "sister colonies" have quite surpassed anything that Sarawak may perhaps hope to acquire in a corresponding number of years.

The trade is mainly in the hands of the Chinese merchants, mostly country born, who are successfully carrying on thriving businesses of which the foundations were laid by their fathers in the early days of the raj. These merchants are of a highly respectable class, and they take the interest of intelligent men in the welfare of the country, which they have come to regard as their own. They rarely visit China – some not at all. They are consulted by the Government in all matters in which their interests are concerned.

The only European Firm is the Borneo Company Limited, and the career of this Company has for over fifty years been so closely linked with that of the State, and so much to the advantage of the latter, that it fully merits more than a passing notice in these pages, without which this history would not be complete.

For a considerable period Mr. J. C. Templer, the late Rajah's old friend, laboured very hard to meet the ignorant and cruel criticism which had been cast on the Rajah's great work, and, in order that the development of Sarawak might have financial support, he interested friends in the city in the matter, chiefly Mr. Robert Henderson of Messrs. R. and J. Henderson.

After considerable negotiation, the Borneo Company Limited was registered in May, 1856. The attention of the Company was turned primarily to supporting the Rajah, and to developing the resources of the country. The first Directors were Messrs. Robert Henderson (Chairman), J. C. Templer, J. D. Nicol, John Smith, Francis Richardson and John Harvey (Managing Director).

Most unfortunately, immediately after the formation of the Company troubles arose which nearly overwhelmed the State. The Chinese insurrection the next year, and the later political intrigues obscured for a time the prosperity of Sarawak, and left the prospects of the Company very black indeed, but it struggled on bravely; and it cannot be doubted that its formation before the insurrection was a matter of great value in the history of the country.

The Company, as soon as they received news of the insurrection, instructed their Manager in Singapore to supply the Rajah with all the arms, ammunition, and stores he might require, and it was their steamer, named after himself, that arrived at such an opportune moment, and enabled him to drive the rebels out of Kuching, and to cut short their work of ruin far sooner than he could otherwise have done; and it was the Company which not only subsequently advanced the Rajah the means he so sorely needed to carry on the government, but headed a subscription list started in England to relieve the Government of pressing wants, with a donation of £1000. Long before this the Rajah's private fortune had been exhausted.

Some appear to have formed the opinion that the Company were subsequently inconsiderate in pressing for payment of the loan, but more consideration should have been given to the position of the Directors as being a fiduciary one to the shareholders, who had invested their money in a commercial enterprise, and at that time by no means a prosperous one.

Since the Company was formed over £200,000 has been paid to the Government for mining royalties, and during the same period £2,000,000 has been paid out in wages, which has tended to the prosperity and advantage of the country.

Until 1898, no balance of profit had been made by the Company from Sarawak; indeed, there was a very considerable deficit, which had been met from the profits of their other operations.357 This persistence in the original policy of the founders of the Company for forty years without return has, however, been rewarded by considerable success in the last decade. The enterprise that brought this success, the extraction of gold from poor grade ores by the cyanide process, is noticed further on, and we will conclude this notice of the Company by a quotation from a speech by the Rajah given thirty years after the foundation of the raj.

The Company has held fast and stuck to its work through the perils and dangers and the adversity which Sarawak has experienced and encountered. It has shown a solid and stolid example to other merchants, and has formed a basis for mercantile operations; and the importance of the presence in a new State of such a large and influential body as the Borneo Company cannot be overrated.

Owing to the absolute lack of security to life and property, both within and without, before the accession of Sir James Brooke to the raj, Sarawak had no trade. After 1842 a small trade began to spring up, but the Lanun and Balenini pirates and the Sea-Dayaks rendered the pursuit of trade very difficult and dangerous. The lessons administered to the latter by the Rajah and Sir Henry Keppel caused these to confine themselves for some time to their homes, and the Foreign exports rose to $60,000 in 1847. Then the coast again became insecure, and it was not until after the battle of Beting Maru, in 1849, that trade made any considerable advance, and it continued to increase until the Chinese insurrection brought the country to the verge of ruin. A brief respite followed, and then came the internal political troubles, and renewed activity on the part of the Lanun and Balenini pirates. But in 1862, the authority of the Rajah was paramount from Cape Datu to Kedurong Point, and the defeat of the pirates off Bintulu in the middle of this year freed the Sarawak coast for ever from these pests. So in 1862 the increase in the value of the trade was over fifty per cent. In 1860, the Foreign imports and exports amounted to $574,097; in 1880 to $2,284,495; in 1900 to $9,065,715; and in 1905 to $13,422,267. Since 1905, in common with all countries, the State has been suffering from commercial depression, and in 1907 the decrease in the imports was $709,162, and in the exports $823,682, compared with 1905, though only $2276 and $166,285 as compared with 1906. But though the exports have fallen off in value, there has been an increase in the quantities of the products exported. As prices fluctuate, the industrial progress of a country is, therefore, better gauged by the quantity rather than by the value of its products, and in 1907, 7000 tons more sago flour, 800 tons more pepper, 7000 oz. more gold, and 150 tons more gutta and india-rubber were exported than in 1905.

Practically Singapore has the benefit of the whole of the Sarawak trade, which is borne in two steamers of 900 tons each under the Sarawak flag, owned by the Sarawak and Singapore S.S. Company, and these maintain a weekly communication between Kuching and Singapore. The coasting trade is carried in three smaller steamers owned by the same Company. There is a small trade in timber with Hong Kong; and a few junks come yearly from Siam and Cochin China.

Agriculture is the foremost industry, and as it is a permanent one, only requiring wise and liberal measures to foster and encourage it, Sarawak is in this respect fortunate, for the natural products of a country, such as minerals and jungle produce, must in time be worked out; and the future of a country is therefore more dependent upon its industries than on its natural products.

In 1907, the value of the cultivated products exported was $3,133,565. Of these sago may be said to be the staple product, and the markets of the world are mainly supplied by Sarawak with this commodity. From it Borneo derives its Eastern name, Pulo-Ka-lamanta-an (the island of raw sago).358 The palm, the pith of which is the raw or crude sago, is indigenous, and there are many varieties growing wild all over the island that yield excellent sago. On the low, marshy banks of the rivers, lying between Kalaka and Kedurong Point, are miles upon miles of what might be termed jungles of the cultivated palm, where fifty years ago there were but patchy plantations. The raw sago as extracted by the Melanaus is purchased by the Chinese and shipped to the sago factories in Kuching, where it is converted into sago flour, in which form it is exported to Singapore. How the cultivation of the sago palm is increasing, the following figures will show: —

359 Quantity not given in published trade returns.

In 1847-48, only 2,000 tons were imported into Singapore, practically all from Borneo.

In times immemorial pepper was very extensively cultivated in Borneo. In the middle ages this cultivation attracted particular attention to the island; and to obtain a control over the pepper trade by depriving the Turks of their control over the trade in spices was one of the main incentives to the discovery of a route to the East by the Cape. By many the introduction of pepper into Borneo is attributed to the Chinese, and from them the natives are supposed to have learnt its cultivation, but this is doubtful, as pepper is not a product of China, and was probably introduced by the Hindus; but that the Chinese, finding the industry a profitable one, improved and extended the cultivation of pepper, there can be no doubt. What the export of pepper was in the days when the Malayan Sultanates were at their prime it is impossible to determine, but that it must have been very considerable is indicated by the fact that as late as 1809 Hunt estimated the export from Bruni at 3500 tons, and at that time the country had been brought to the verge of ruin by misrule and oppression, which led to the gradual extinction of the Chinese colony, and to the deprival of all incentive to the Muruts and Bisayas to carry on an industry for which they had once been famous – indeed, Hunt notices that he saw numbers of abandoned gardens, and his observations were restricted to a very limited area. In spite of the harmful restrictions of the Dutch, in the south at Banjermasin, two hundred years ago, the export was still from 2000 to 3000 tons.359 Had different conditions prevailed, had native industry been encouraged instead of having been suppressed, then truly might Borneo have become the "Insula Bonæ Fortunæ" of Ptolemy.