полная версия

полная версияTwo Wars: An Autobiography of General Samuel G. French

As Minerva sprung from the brain of Jupiter, full grown, robed in the panoply of war, and took her seat among the gods, so the Confederate States – born in a day, clothed in all the attributes of government, complete in every department – took her station among the nations of the earth. She exacted from the United States the observance of international law on war and official intercourse. After four years of the most sanguinary war of modern times she fell, white and pure, before the mercenary hosts of the nations arrayed against her. She died for the priceless heritage wrung from tyrants "that all just powers of government are derived from the consent of the governed."

For this inalienable right – a right that has been exercised by almost every nation on earth, and for which millions and millions of lives have been sacrificed – the States seceded, and it will never die. It was implanted by Providence like religion in the hearts of mankind. It is an invisible power behind a veil that will break through as certainly as the soul at death lifts the dim veil that hides the life beyond the grave. It is an occult power pervading the air, and gentle until developed by oppression, whether by bad government or remorseless tyranny incident to aggregated wealth or other causes. It was not the victories of the Confederate armies; it was not because they gave the world a Lee, a Johnston, a Forrest, and a Stonewall Jackson that won the admiration of the nations; but because over all these the South was true to her convictions of right. Their achievements were great, but their cause was greater; their deeds are immortal, their cause eternal, and paid for in blood. It will exist till the leaves of the judgment book unfold.

I must now take my farewell of the good Confederate soldiers with whom I have had the honor to serve. I know their valor and their worth. Like the sibylline books, as they diminish in numbers they will increase in value, and with the last veteran the order will end – then silence! Their valor will be the common heritage of mankind. Their memory will be revered by their posterity, and linger in the mind as sweetly as the fragrance of flowers. Their cause let none gainsay; it is the birthright of all the ages.

To you, my children, I have related some of my observations, and given a little of my experience in this wonderful nineteenth century.

In my youth dwellings were lit up with candles; then came gas and kerosene; now electricity illumes cities and streets, cars and ships. Steam power was known, but it had not been applied to railroads or steamships on the ocean, or to many mechanical purposes. How well do I remember the many journeys I made over the Alleghany Mountains by stage to Pittsburg, Brownsville, and Wheeling, and how steam power superseded horse power in ferryboats, treadmills, and sailing vessels on the ocean!

I have told you how I went with Prof. Morse to receive what may be deemed the first message of the telegraph; now we send messages around the world.

In 1862 I saw a telephone established from one house to another, distant about fifty yards, by two young ladies in Wilmington, N. C., to communicate with each other. To-day we talk face to face a thousand miles.

The discovery of anæsthetics has alleviated the pain of the surgeon's knife, and with the X ray he looks through the human body, and makes visible the location and cause of pain, etc.

During this century the map of the world has had many changes by the Napoleonic wars, the upheaval of 1840 by Garibaldi, Bismarck, Germany, and France; and all Africa is subjugated. In the Orient – that empire of occult science and mystery, of magic, fakirs, castes, and barbaric wealth; six times invaded from the West through the gates of India by Alexander, Mahmoud, Genghis Khan, Tamerlane, Monguls, and Persians – at last, in this century, with a population of over 300,000,000, has passed into the possession of England, and Queen Victoria is Empress of India! What destiny awaits China, with her 400,000,000 people?

We have witnessed Spain lose possession of all her colonies in South America, Mexico, and her West Indies possessions and the Philippine Islands; the slave trade, conceded to New England, ended only in 1808; imprisonment for debt was in existence when I was young in some of the States – in short, such has been the progress of liberty during this closing century that it has turned the world upside down, and to all oppressors from any cause the spirit of liberty cries:

"By all ye will or whisper,By all ye leave or do,The silent sullen peopleShall weigh your God and you."APPENDIX

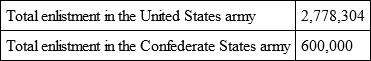

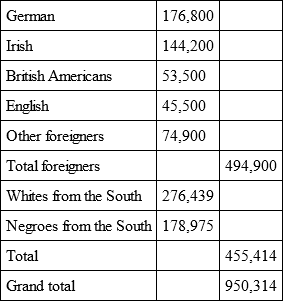

Some Statistics of the War.

FIRST.

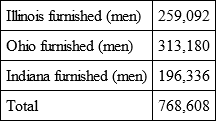

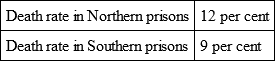

Number of Foreigners in the United States Army.

Here you will discover a force 350,414 stronger than the whole Confederate army, without enlisting a native-born citizen of the North; also that the South furnished the North 455,414 men.

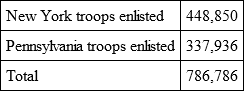

SECOND.

Here is an army larger than the Confederate States army.

THIRD.

Here we have a second army larger than the Confederate army.

FOURTH.

Here is a third army larger than the Confederate army, and the fourth army came from the excess of numbers in the three preceding ones.

But the most remarkable fact is, that there were in the United States army 950,314 men that should be called foreigners, as none belonged to the North by birth.

In connection with the number of foreigners in the United States army, I will remark that Gen. Benjamin F. Butler, of Massachusetts, in his argument before the Tewksbury Almshouse investigating committee, July 15, 1883, said: "Before you go to throwing ridicule on the foreign-born, let me tell you that you had better look into the question of who fought your battles. In the first place, look at the per cent of what birth the inmates in our soldiers' homes were; fifty-eight and one-half per cent of the soldiers in these homes are of foreign birth."

Again he said: "Some of us stayed at home and pressed soft cushions of skinned paupers while these foreigners so much sneered at were fighting our battles."

In regard to the tanning of the skins of the dead inmates of the almshouse, Butler quotes from Carlyle (page 354), and goes on to say that at Meudon the skins of the guillotined were turned into good wash leather and made into breeches for paupers. So the paupers in France were dressed in the skins of my lord and lady, "while in Massachusetts it was our aristocrats that wore slippers made from the breasts of women paupers." Matters here are reversed – it is my lord and lady who wear such slippers.

It may be of some interest to quote further from Butler. In contrasting the expenses of the soldiers' home (one of them) he said it took 278 turkeys for their Thanksgiving dinner, and their last "potpie" required 34 sheep, 15½ barrels of potatoes, and 2 barrels of flour. During the year they ate 758 head of cattle, 1,659 head of sheep, 3,714 barrels of flour, 15,744 dozen eggs, 154,932 pounds of butter, 69,289 pounds of coffee, 57,941 pounds of fish, 7,950 pounds of tea, 10,570 cans of tomatoes, 16,431 pounds of rice, 110,440 pounds of sugar, 21,325 pounds of prunes, and other articles too numerous to mention, amounting to the sum of $204,728, hereby establishing that the inmates of the soldiers' home were fed cheaper and better than the paupers of the Tewkesbury almshouse.

I refrain from naming the horrors of this institution in Massachusetts; but the men who are fond of the horrible depravity of mankind, for money, can find their taste gratified in Butler's pamphlet, illustrated by photographs of tanned skins, etc.

Civilization, even among the cultured, is sometimes a diaphanous garment to hide the infernal. "Nature still makes him; and has an infernal in her as well as a celestial."

Well might it be said by an English writer that "the men in the North could, for a moderate sum, engage substitutes to vicariously die for them, while they sipped their wines at the clubs in safety."

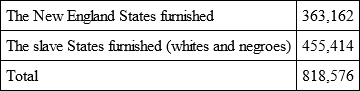

Percentage Killed and Wounded in Late Wars.

This question, as far as I am informed, has not been analyzed to separate it from the concrete mass of men that composed the Confederate army. This is desirable to establish what influence they had in deciding the Southern States to secede from the Union, and the solution of it should give the number of slave owners in the army.

The white population of these States was, in 1860, about 8,300,000. There were 346,000 whites who owned slaves. These figures represent and include men of all ages, widows, and minors: also young married women who owned the servant usually given them.

Now divide 8,300,000 by 346,000, and we have 8,300,000/346,000==24, which shows that only one person in twenty-four was a slaveholder, and we know not what number in this twenty-four were women, orphans, and old men. If allowance be made for the old men, women, and minors, there would not be over four able-bodied men to the one hundred; hence in a company of one hundred soldiers four would be slave owners. In a regiment of one thousand there would be forty, in ten thousand there would be four hundred, and in the whole Confederate army of six hundred thousand there would be only twenty-four thousand who represented slavery. The remainder (600,000-24,000) would be 576,000 who were not slave owners! This number, however, might be reduced by young men heirs apparent of slaves.

Henceforth, then, let it be known that the Confederate army was not an army of slave owners. To the people of the South it was well known that the slaves were fast becoming the property of the owners of large estates, and on many sugar and cotton plantations there were from one to two hundred negroes employed. The tendency was to consolidate labor, as it was more profitable. Therefore it was that the Confederate army was mainly composed of men as free from interests in slavery as were the men living in sight of Bunker Hill. These men were contending for an object far more dear to them than any arising from slavery. They had seen the accumulated funds of the United States treasury expended in making harbors for towns on the great Northern lakes yearly, and in digging deep-water channels for Eastern cities, and appropriations for little creeks called rivers; while the harbors of the Southern cities were neglected. Then, again, the tariff almost invariably discriminated against the South, even to the extent of nullification, almost thirty years anterior to the war; then the fugitive slave act was nullified by Northern State laws; "underground railroad" was a term used to express how negro slaves were conveyed under cover of the night to the North when enticed from their owners. They openly published that the Constitution was a "compact made with the devil;" and the hatred of the North and the West was so widespread that by a sectional party vote they elected a President antagonistic to the South. These are but a few of the acts that caused secession; and yet he who believes that secession was entertained by more than a mere majority of the people South is mistaken. Genuine love and an abiding fidelity to the Constitution were ever found in the South. Her cause for complaint also was that the people of the North and West, actuated by hatred of the people South, proclaimed that the higher law of conscience was superior to the Constitution!

Events came on apace. The Southern people were homogeneous, "to the manner born." Save only in the commercial cities were there any foreigners and but few Northerners. North Carolina did not have quite one per cent foreign; the West had about thirty-five per cent. (Census Report.)

When coercion of the South was proclaimed, it was the homogeneousness of her people that solidified both parties at once to a common defense of their homes, and these five hundred and seventy-six thousand soldiers, without interest in slavery, for four years fought for the right of their people to govern themselves in their own way. Their deeds are now a matter of history that will, by them, be recorded, contrary to the past rule, that the conquerors always write history.

Appomattox terminated the war only – it was not a court to adjudicate the right of secession – but its sequence established the fact that secession was not treason nor rebellion, and that it yet exists, restrained only by the question of expediency. Wherefore the Union will be maintained mainly by avoiding sectional and class legislation, and remembering always that in the halls of legislation the minority have some rights, and in the minority the truth will generally be found.

The charge, then, that the slaveholders, so few in number, forced secession, or that the five hundred and seventy-six thousand nonslaveholders who really constituted the Confederate army were battling to maintain slavery, is a popular error.

The cry at the North that the South was fighting to maintain slavery was proclaimed (as I have elsewhere said) to prejudice the Emperor Napoleon III. and the English Cabinet against forming an alliance with the Confederate States; but the power of public opinion and the press were such that they were obliged to remain neutral; for this constrained neutrality England was rewarded by being forced, when the war ended, to pay the United States the sum of fifteen million dollars – the Geneva award– for the ships destroyed by Admiral Raphael Semmes, Confederate States Navy; and France was rewarded by obliging Napoleon to withdraw his troops from Mexico, and leave poor Maximilian to his fate – a warning for weak men thirsting for empire.

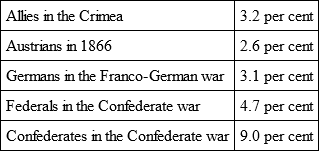

Prison Deaths and PrisonersThe number of Confederate prisoners in Northern prisons was 220,000, and the number of Federal prisoners in prisons South was 270,000.

See the report of Secretary Stanton, made July 9, 1866; also the report of Surgeon General Barnes, United States Army.

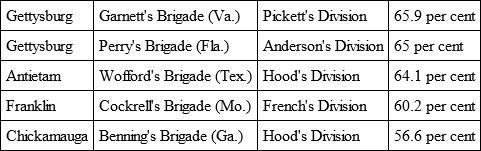

Some of the Brigade Losses in Particular Engagements.

There are thirteen more brigades with losses, varying in numbers, before the percentage is reduced to forty per cent.

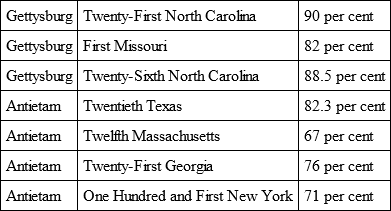

Percentage of Loss in Some Regiments in Single Battles.

And so on. There are over fifty regiments in the Confederate army before forty per cent is reached. How many there are in the Federal army I do not know. (From "The Confederate Soldier in the Civil War," and other sources.)

The Authority to Taxis the greatest power a people can give a government, yet it is a necessary measure, but often dangerous; it can be used to impoverish a people, or enrich a comparatively few individuals, or to rob one section of a vast country to build up another. It has caused more distress than droughts or floods; it has caused more insurrections, revolutions, and wars than all other acts of man intrusted with authority. There are many modes of taxation, but the most insidious one is the quiet robbery by a tariff.

This might be demonstrated by the United States pension laws. The pensioners (and I am a Mexican war pensioner) receive as a free gift from the treasury the sum of about one hundred and fifty million dollars annually. It goes to enrich the people of the States where they reside.

If there be no pensioners living in any one State, that State contributes to support the pensioners, but receives nothing in return: so, if all the pensioners were to become citizens of any one State, that State would receive in pension money one hundred and fifty million dollars yearly, or in fifteen years the enormous sum of two billion two hundred and fifty million dollars derived by taxation of the people in the other States, less the sum that one State paid and returned to it.

Now, if all the pensioners, from any cause, should migrate to Ohio, or North Carolina, would the other forty-four States be taxed for (say) the benefit of the people of the State of North Carolina in the sum of two billion two hundred and fifty million dollars during the next fifteen years? No, never.

The presumption is that the Southern States pay, under the revenue laws, one-third of the revenue collected. If so, then the South pays the pensioners about fifty million dollars annually, and receives in return only the small sum paid the few pensioners residing within the Southern States; and thus one section of the country is taxed, under the revenue tariff laws, to enrich the other, Q. E. D.

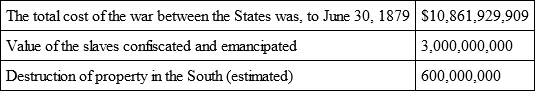

Cost of the War.

The following enumeration of the vessels in the United States service will convey some idea of the power of the North:

Seven hundred vessels were employed in blockading our coast and guarding our rivers.

During the year 1862-63 there were 533 steamers, barges, and coal boats belonging to the United States on the Mississippi river and its tributaries; and at the same time the United States Quartermaster's Department chartered 1,750 steamers and vessels to aid Gen. Grant in his operations against Vicksburg. In short, there were 2,283 vessels, exclusive of iron-clad mortar boats, operating to capture Vicksburg. The actual siege commenced May 18, and ended July 4, 1863, embracing a period of forty-seven days.

Names, Rank, and Positions of Officers on My Staff• Abercrombie, Wiley, Lieutenant, Aid-de-Camp.

• Anderson, Archer, Major, Aid-de-Camp.

• Archer, C., Lieutenant, Ord. Officer.

• Baker, J. A., Captain, Aid-de-Camp.

• Baldwin, John M., Captain, Acting Ord. Officer.

• Cain, W. H., Captain, Commissary.

• Danner, Albert, Captain, Quartermaster.

• Daves, Graham, Major, A. A. General.

• Drane, N. M., Captain, Quartermaster.

• Freeman, E. T., Lieutenant, A. A. I. General.

• Haile, Calhoun, Lieutenant, Aid-de-Camp.

• Harrison, William B., Major, Chief Surgeon.

• Morey, John B., Major, Chief Quartermaster.

• Myers, C. D., Lieutenant, Aid-de-Camp.

• Overton, M., Captain, Ord. Officer.

• Reynolds, F. A., Captain, A. A. General.

• Robertson, N. H., Lieutenant, Artillery.

• Rogers, H. J., Captain, Engineer.

• Sanders, D. W., Major, Adj. General.

• Shingleur, James A., Lieutenant, Maj. and A. A. G.

• Shumaker, S. M., Major, Chief Artillery.

• Storrs, George S., Lieutenant, Maj. and Chief Art.

• Venet, John B., Captain, Engineer.

• Yerger, James R., Lieutenant, Aid-de-Camp.

• Thomas, Grigsby E., Sergeant, Ordnance.

Government in Louisiana, 1875-76The forces that were developed during the last two years of the war found a wide field for operation as the Union troops marched through the South, and induced the troops to plunder, because there was money in it, and when the war ended this force entered the wide area of reconstruction, and produced those cursed scenes witnessed all over the South, because there was money in it, and yet when the States were admitted into the Union it was natural to suppose that its power for evil was spent. Not at all; it rallied, and entered the field of politics; debased by all the license of war, which exempted them from punishment for all crimes, they sold themselves for a price, and the dual governments commenced: the one established by the property owners and respectable people, the other by the carpetbaggers, scalawags, and negroes. Here were offices by election and by appointment affording almost unlimited opportunity to plunder. They had no conscience when they could put money in their pockets.

To illustrate, I will, as briefly as I can, take the State of Louisiana. In 1875 this State had two rival courts, two opposing Legislatures. One was the radical carpetbaggers, and the other conservative. There were three governors; also United States Senators, black and white, and Gen. P. H. Sheridan was military director; and over and above all the United States intermeddling in her affairs. The rival courts were occupied in reversing the decisions of each other, the Legislatures in passing bills that were not valid for the want of a quorum, or obtaining the signature of the right governor, whether of Kellogg, Warmouth, or McEnery (the three governors).

As this threefold government presaged the probability of the radical party not receiving the electoral vote of the State in the coming election for President, something had to be done to accomplish it. Accordingly the President directed the Secretary of War to issue an order directly and secretly to Gen. P. H. Sheridan, who was in Chicago, to proceed to New Orleans, and it was suggested that he should make the journey appear as one undertaken for recreation. So he and some of his staff, and a party of ladies on pleasure bent, sailed down the turbulent Mississippi river to New Orleans, and established headquarters in the St. Charles Hotel.

Sheridan's secret orders, dated December 24, 1874, were sent to him direct from the Secretary of War, and without the knowledge of Gen. Sherman, commanding the army, or of Gen. McDowell, commanding the Department of the South, which embraced Louisiana, with his headquarters in Louisville, Ky.; but he was advised that he might stop and make known to Gen. McDowell the object of his mission if he deemed it proper to do so, but he passed by without seeing McDowell. On arriving in New Orleans he made the State of Louisiana a part of his department, and then issued his decree declaring the people of the state "banditti." This alarmed the President. It was too imperialistic. Sheridan then suggested that Congress be called on to pass an act in a few words making the people banditti. The President declined. Then the chief of the banditti advised the President to issue an order through the War Department declaring the people banditti, and to leave ALL TO HIM, and he would quell them without giving him (the President) any further trouble. In all this there is a thirst for blood and punishment by military authority. But Grant, sitting on the ragged edge of imperialism, declined to support his man-of-all-work on the banditti question. But still undaunted, Sheridan perchance recalled to mind how Cromwell entered the "Praise God Barebone" house of Parliament, and, charging the members to be guilty of dishonorable acts, drove them out of the house by an armed force, locked the door, and put the key in his pocket; or how Napoleon entered the hall of the council of live hundred in Paris, and at the point of the bayonet dissolved the convention – resolved to imitate those great men by taking a company of the United States army, and thrust the members of the conservative Legislature into the street. This he did by sending Gen. De Trobirand to close the legislative hall of a sovereign State in the Union, first ejecting the members.

However much the North was willing to punish the South, they saw in this a usurpation of United States authority which, if unrebuked, might be applied to a "truly loyal" State in the North; and now the Northern press howled, not because it had been done in Louisiana, but for fear their Legislatures might be invaded likewise, and they cried: "Have we also a Cæsar?" And all this was done to secure the vote of Louisiana to the radical party in the coming presidential election.