полная версия

полная версияSocial Origins and Primal Law

ILLUSTRATION FROM FOLK-LORE

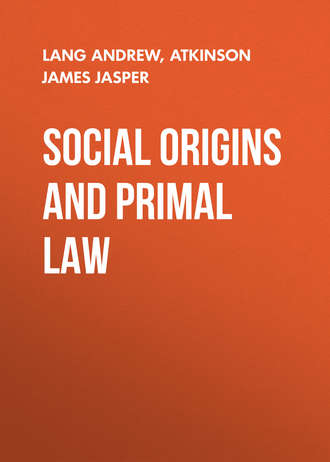

I select illustrative examples from the blason populaire of modern folk-lore. Here we find the use of plant and animal names for neighbouring groups, villages, or parishes. Thus two informants in a rural district of Cornwall, living at a village which I shall call Loughton, found that, when they walked through the neighbouring village, Hillborough, the little boys 'called cuckoo at the sight of us.' They learned that the cuckoo was the badge, in folk-lore, of their village. An ancient carved and gilded dove in the Loughton church 'was firmly believed by many of the inhabitants to be a representation of the Loughton Cuckoo,' and all Loughton folk were Cuckoos. 'It seems as if the inhabitants do not care to talk about these things, for some reason or other.' A travelled Loughtonian 'believes the animal names and symbols to be very ancient, and that each village has its symbol.' My informants think that 'some modern badges have been substituted for more ancient ones,' such as tiger and monkey. There is apparently no veneration of the local beast, bird, or insect, which seems often, on the other hand, to have been imposed from without as a token of derision. Australians make a great totem of the Witchetty Grub (as Spencer and Gillen report), but the village of Oakditch is not proud of its potato grub, the natives themselves being styled 'tater grubs.' I append a list of villages (with false names230) and of their badges:

At Loughton, when the Hillborough boys pass through on a holiday excursion, the Loughton boys hang out dead mice, the Hillborough badge, in derision. The boys have even their 'personal totem,' and a lad who wishes for a companion in nocturnal adventure will utter the cry of his peculiar beast or bird, and a friend will answer with his. If boys remained always boys (that is, savages), and if civilisation were consequently wiped out, myths about these group names of villages would be developed, and Totemism would flourish again. Later I give other instances of village names answering to totem names, and in an Appendix I give analogous cases collected by Miss Burne in Shropshire, and others, we saw, are to be found in the blason populaire of France.

It appears to me that totem group names may, originally, have been imposed from without, just as the Eskimo are really Inuits; 'Eskimo,' 'Eaters of raw flesh,' being the derisive name conferred by their Indian neighbours. Of course I do not mean that the group names would always, or perhaps often, have been, in origin, derisive nicknames. Many reasons, as has been said, might prompt the name-giving. But each such group would, I suggest, evolve animal and vegetable nicknames for each neighbouring group. Finally some names would 'stick,' would be stereotyped, and each group would come to answer to its nickname, just as 'Pussy Moncrieff,' or 'Bulldog Irving,' or 'Piggy Frazer,' or 'Cow Maitland,' does at school.

HOW THE NAMES BECAME KNOWN

Here the questions arise, how would each group come to know by what name each of its neighbours called it, and how would hostile groups Come to have the same nicknames for each other? Well, they would know the nicknames through taunts exchanged in battle.

'Run, you deer, run!''Off with you, you hares!''Skuttle, you skunks!'They would readily recognise the appropriateness of the names, if derived from the plants, trees, or animals most abundant in their area, and most important to their food supply: for, at this hypothetical stage, and before myths had crystallised round the names, they would have no scruples about eating their name-giving plants, fruits, fishes, birds, and animals. They would also hear their names from war captives at the torture stake, or on the road to the oven, or the butcher. But the chief way in which the new group names spread would be through captured women; for, though there might as yet be only a tendency towards exogamy, still girls of alien groups would be captured as mates. 'We call you the Skunks,' or whatever it might be, such a bride might remark, and so knowledge of the new group names would be diffused. These names would adhere to groups, on my hypothesis, already exogamous in tendency, and, when the totem myth arose, the exogamy would be sanctioned by the totem tabu.231

TOTEMIC AND OTHER GROUP NAMES – ENGLISH AND NORTH AMERICAN INDIAN

It may seem almost flippant to suggest that this old mystery of Totemism arises only from group names given from without, some of them, perhaps, derisive. But I am able to demonstrate that, in North America, the names of what some American authorities call gentes (meaning old totem groups, which now reckon descent through the male, not the female line), actually are nicknames – in certain cases derisive. Moreover, I am able to prove that, when the names of these American gentes are not merely totem names, they answer, with literal precision, to our folk-lore village sobriquets, even when these are not names of plants or animals. The late Rev. James Owen Dorsey left, at his death, a paper on The Siouan Sociology.232 Among the gentes (old totem kindreds with male descent) he noted, the gentes of a tribe, 'The Mysterious Lake Tribe.' There were, in 1880, seven gentes. Three names were derived from localities. One name meant 'Breakers of (exogamous) Law.' One was 'Not encumbered with much baggage.' One was Rogues ('Bad Nation'). These three last names are derisive nicknames. The seventh name was 'Eats no Geese,' obviously a totemic survival. Of the Wahpeton tribe all the seven gentes derived their names from localities. Of the Sisseton tribe, the twelve names of gentes were either nicknames (one, 'a name of derision'), or derived from localities.

Of the Yankton gentes, five names out of seven were nicknames, mostly derisive, the sixth was 'Bad Nation' ('Rogues'), the seventh was a totem name, 'Wild Cat.' Of the Hunpatina (seven gentes), three names were totemic (Drifting Goose, Dogs, Eat no Buffalo Cows); the others were nicknames, such as 'Eat the Scrapings of Hides.' Of the Sitcanxu, there were thirteen gentes. Six or seven of their titles were nicknames, three were totemic, the others were dubious, such as 'Smellers of Fish.' The Itaziptec had seven gentes; of their names all were nicknames, including 'Eat dried venison from the hind quarter.' Of the Minikooju, there were nine gentes. Eight names were nicknames, including 'Dung Eaters.' One seems totemic, 'Eat no Dogs.' Of five Asineboin gentes the names were nicknames from the habits or localities of the communities. One was 'Girl's Band,' that is, 'Girls.'

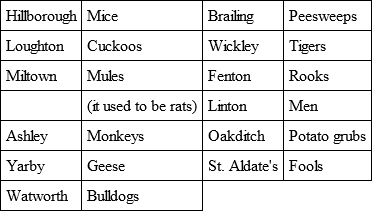

Now compare parish sobriquets in Western England.233 In this list of parish or village nicknames, twenty-one are derived from plants and animals, like most totemic names. We also find 'Dog Eaters,' 'Bread Eaters,' 'Burd Eaters,' 'Whitpot Eaters,' and, answering to 'Girl's Band' (Gens des Filles), 'Pretty Maidens:' answering to 'Bad Nation,' 'Rogues': answering to 'Eaters of Hide Scrapings' 'Bone Pickers': while there are, as among the Siouans, names derived from various practices attributed to the English villagers, as to the Red Indian gentes.

No closer parallel between our rural folk-lore sobriquets of village groups, given from without, and the names given from without of old savage totem groups (now reckoning in the male line, and, therefore, now settled together in given localities) could be invented. (For other examples see Appendix A.) I conceive, therefore, that my suggestion – the totem names of pristine groups were originally given from without, and were accepted (as in the case of the nicknames of Siouan gentes, now accepted by them) – may be reckoned no strain on our sense of probability. It is demonstrated that the name-giving processes of our villagers exist among American savage groups which reckon descent in the male line, and that they also existed among the savage groups which reckoned descent in the female line is, surely, a not unreasonable surmise. I add a list in parallel columns.

Примечание 1234

THEORY THAT SIOUAN GENTES NAMES ARE OF EUROPEAN ORIGIN

To produce, from North America, examples of group names conferred from without, as in the instances of our English villages, may, to some students, seem inadequate evidence. For example an unconvinced critic may say that the nicknames of Mr. Dorsey's 'Siouan gentes' were originally given by white men; the Sioux, Dacota, Asineboin, and other tribes having been long in contact with Europeans. Now it is quite possible that some of the names had this origin, as Mr. Dorsey himself observed. But no critic will go on to urge that the common totemic names which still designate many gentes were imposed by Europeans who came from English villages of 'Mice,' 'Cuckoos,' 'Tater Grubs,' 'Dogs,' and so forth. We might as wisely say that our peasantry borrowed these village names from what they had read about totem names in Cooper's novels. To name individuals, or groups, after animals, is certainly a natural tendency of the mind, whether in savage or civilised society.

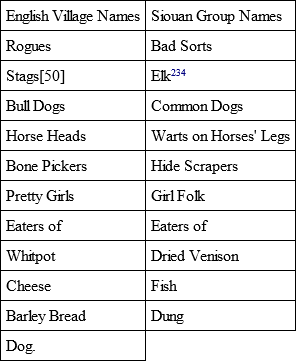

If we take the famous Mandan tribe, now reckoning descent in the male line, but with undeniable survivals of descent in the female line, we find that the gentes are:

Here, out of seven gentes, four names are totemic; one is a name of locality, 'High Village,' not a possible name in pristine nomadic society. While there are hundreds of such cases, we cannot reasonably regard the American group nicknames as generally of European origin. Still more does this theory fail us in the case of Melanesia, where contact with Europeans is recent and relatively slight. Among such tribes as the Mandans, and other Siouan peoples, we see Totemism with exogamy and female kinship waning, while kinship, recognised by male descent, plus settled conditions, brings in local names for gentes, and tends to cause the substitution of local names and nicknames for the totem group name. Precisely the same phenomena meet us, as we are to see, in Melanesia.

CHAPTER IX

THE MELANESIAN SYSTEMS

We have, fortunately, an opportunity in Melanesia of studying, as it seems, the Australian marriage system in a state of decay.235 The institutions of Melanesia bear every note of being Australian institutions, decadent, dislocated, contaminated and partially obliterated. Starting from New Guinea, we find a long archipelago sloping down, away from the east side of Australia, towards the Fiji Islands. The archipelago consists mainly, in the order given, of New Ireland, New Britain, the Solomon Group, Banks Island, the New Hebrides, Loyalty Island, and New Caledonia. The inhabitants are a fusion of many oceanic elements, and are much more advanced in culture than the natives of Australia: they have chiefs, whose office tends to be hereditary (and in one place, Saa, is hereditary), in the male line, the father handing on to the son his magical acquirements and properties, and leaving to him his wealth, as far as he may. This is not very far, as, curious to say, descent in the female line is generally prevalent. Wealth is both real and personal: landed property consisting (1) of Town Lots, (2) of Gardens (ἓρκος), (3) of the Waste ('the Bush'). The 'town lots' and gardens pass by inheritance; the possessor being only 'possessor,' not proprietor, and real property passing in the female line, where that line still prevails. The reclaiming of land from the Waste tends, however, to direct property into the male line, which, except in certain districts, is not dominant. Money is divided, on a death, among brothers, nephews – and sons, 'if they can get it' – the money being the native shell currency. The tendency towards the substitution, as heirs, of a man's sons for his sister's sons, is powerful.236

This is a curious and anomalous condition of the family. As regards material advantages (χορηγία, Greek [choreigia]) Melanesian society is greatly in advance of Australian. It is in possession of houses, fruit trees, agricultural allotments, domesticated animals, and a native currency. Thus there is much property to be inherited, and where that is the case, and where the family has a house of its own, the desire of men to leave their goods and dwellings to their sons usually results in the reckoning of descent on the sword side. Yet, in this respect, the Melanesians of many regions are behind the naked, houseless Arunta, and other Australian tribes with male descent.. What influences caused these tribes to depart from the reckoning in the female line, still used among their equally destitute neighbours, the Urabunna, is a most difficult question; indeed the number of distinct grades, in relation to family laws among the Australians, is an enigma. Among the Melanesians, at all events, material advance and accumulation of property have often failed to bring inheritance out of the female into the male line.

Insular conditions are apt to develop divergences from any given type – local varieties – while the mixture of races, and the introduction into one island, or part of it, of the customs of settlers from other islands, produces peculiarities and anomalies in Melanesia. We expect, therefore, to find Melanesian marriage rules rather dislocated and contaminated, and to see that the archaic type is half obliterated. In fact, this is the case, and Totemism, if it exists, survives in fragments and vestiges.

'Where are the totems?' Dr. Codrington asks, and we can only reply that they seem to be half obliterated. 'Nothing is more fundamental than the division of the people into two or more classes, which are exogamous, and in which descent is counted through the women.'237 This answers to the Australian 'primary divisions,' or 'phratries.' But, in Australia, as we showed, these divisions appear to be of totemic origin. If this was so, in Melanesia, the evidence for the fact is much less distinct. In a large region of the Solomon Islands 'there is no division of the people into kindreds, as elsewhere, and descent follows the father… The particular or local causes which have brought this exceptional state of things are unknown.'238

Speaking generally, however, the two primary exogamous classes exist, and to a Melanesian man, all women of his own generation count either as 'sisters' (barred) or as (potential) 'wives.' The appropriation of actual wives to their actual husbands 'has by no means so strong a hold on native society,' as the exogamous class divisions. By many students this license will be considered a survival of 'group marriage.' Prenuptial unchastity is wrong, but a breach of the exogamous rule used to be punished by death. Wife-lending used to be common, as in Central Australia, if the wife and guest were of opposite 'divisions.' Whether the license of certain feasts (as among Australians and Fijians) smiles on breaches of the exogamous law, does not seem quite certain.239

In Banks Island and the North New Hebrides, there are but the two 'primary class divisions.' These have not names as in Australia – if once they had names, the names are lost. We find merely 'divisions' (veve), two 'sides of the house.' Every man knows his own division; all the women in it are tabu to him; all the women of the other division, in the same generation, are potential wives (with certain restrictions in practice).

In Merlav, one of the Banks Islands, there are 'families within the kin' (answering to gentes– totem kins – in Australia). These families have local names, as a rule: one has its name from the Octopus, but eats it freely.

It is not inconceivable that here we have broken down and obliterated Totemism, among a settled agricultural people, probably dwelling, as a rule, in close contiguity.

In Florida, and adjacent parts of the Solomon Islands, not merely two, but six 'kema' or exogamous divisions ('phratries?') exist. Two of the six have names derived from localities, two have animal names, Eagle and Crab: two kema came in from abroad. All this points to contamination, and rearrangement, under new circumstances. Each kema in Florida has one or more buto, the clam, pig, pigeon, and so on, not to be eaten by members of the kema. This looks like the 'totemic subdivisions' (that is, the totem groups within the 'phratries') of the Australians. Again, these butos within each kema, animals and plants not to be eaten, are exactly like the survivals of Totemism in the names of the Siouan totem kins with male descent, 'Do not eat small Birds,' 'Do not eat Dogs,' 'Do not eat Buffalo,' and so forth. The buto of each kin within the Melanesian exogamous kemas, then, seems to me to be the old totem of the kin, now relegated to a position more obscure, in the changes of society, and, with one exception, not giving its name and tabu to the kema. Only in one case is the animal which is the buto, also the animal which gives its name to the kema. The Kakau kema may not eat Kakau – the crab. The Manukuma (eagle) kema may eat the eagle: one fancies that they find it tough. In the same way the Narrinyeri and other tribes in Australia permit their totem kins to eat their totems. Members of each kema are apt to speak of their butos (which they may not eat) as their ancestors, as in Totemism, but this is a mere mythical explanation of why they may not eat the buto. With half a dozen other myths, it is used by totemists to explain why they may not eat their totems.

Dr. Codrington, on the other hand, writes, 'the buto of each kema is probably comparatively recent in Florida, it has been introduced at Bugotu within the memory of living men.'240 Dr. Codrington, as we have already seen, inclines to the theory which derives totems originally from individuals. He cites Mr. Sleigh, of Lifu (mentioned by us before), who writes, 'When a father was about to die, surrounded by members of his family, he might say what animal he will be, say a butterfly or some kind of bird. That creature would be sacred to his family, who would not injure or kill it; on seeing or falling in with such a creature the person would say, "That is kaka" (papa), and would, if possible, offer him a young cocoa-nut. But they did not thus adopt the name of a tribe.'241

We need not repeat the objections to all such theories of the derivation of pristine totem group names from individuals, The butos, ancestors, not to be eaten, have all the air of archaic totems, now reduced to a lower plane, and, save in one case out of six, not giving the name to a kema, in Florida. Thus the butos of each kema would be, originally, totemic, but immigrations, settled conditions, the tendency to male descent, and the introduction of local or place names for some groups, of nicknames for others, broke down the old totemic nomenclature, leaving only the Kakau, or crabs, true to their colours and to their totem and totem name, while the other kemas got local names or nicknames – the Hongokikki being named from the pastime of Cat's Cradle – clearly a nickname. Apparently the pigeon is their buto. How did these conditions arise?

Say that there were once four exogamous totem groups in Ettrickdale – Grouse, Deer, Hares, Partridges. Say that there came in two alien groups, Trout and Plover. Of these two, one might come to be called Quoits, from their skill in that game. – Two of the original four might get local names, from their places of residence, say Singlee and Tushielaw. One might keep its old totem, Grouse, and its old totem name, abstaining from grouse. One might get a new name, Roe Deer, but all, under the names of Tushielaw, Singlee, Quoits, Roe Deer, and Grouse (with another not given), would retain their old totems as butos, ancestral in some way, and not to be eaten. But the new, not the totemic, names would now mark off the exogamous kemas. Something of this kind must have occurred in Florida, under new social conditions, and the stress of immigrants. But Dr. Codrington gives a case in which the banana was tabued, just before his death, by 'a man of much influence who said that he would be in the banana.'242

This origin of Totemism (namely, in animism, a man of influence tabuing, and bequeathing to his descendants for ever, the animal or plant that is to be his soul vehicle) is approved of, as the original cause of Totemism, by Dr. Wilken. But could it arise in a much lower state of society, wherein 'men of much influence' are rare, and are readily forgotten? Now in Melanesia, generally, a man's fame, however great, perishes with those who remember him in his life.243 Again, this sort of tabuing the banana affected 'all the people' of the isle Ulawa, and so could not be the base of an exogamous prohibition, unless all brides were to be brought in from foreign islands. If the prohibition was confined to known descendants of the banana man, then we have the patriarchal family, founded by a known ancestor, and exogamous. Now, in Ulawa, descent is reckoned in the male line, and there are no exogamous divisions.244 'This is an exceptional state of things,' says Dr. Codrington (p. 22), yet he thinks it (p. 32) 'in all probability' —plus the tabuing of an object by a dying patriarch – the cause of the buto prohibition in the kemas of Florida. Thus a solitary case from an isle without exogamous divisions ('the only restriction on marriage is nearness in blood'), and with male descent, is supposed by Dr. Codrington to cause the buto prohibition in an island with exogamous divisions, and with female descent.245

His theory is manifestly inconsistent with his facts – moreover, it involves the existence of the patriarchal system at the time when totems first arose.

On the whole, this reasoning does not convince, but, if Dr. Codrington is right, Melanesian institutions are shattered, dislocated, contaminated, and worn down to a remarkable degree. Yet, behind them, where the two, or the six exogamous divisions prevail, with descent counted in the female line, we can scarcely help recognising a basis of Australian customary law, with obsolescence of the totem, slowly tending towards inheritance through the father. 'A chief's sons are none of them of his own kin; and, as will be shown, he passes on what he can of his property and authority to them.'246 In spite of the 'generation names,' 'father,' 'brothers and sisters,' 'children,' the real distinctions of own father, cousin, and so forth, are understood, and expressed, as they usually are, everywhere.247

Thus Melanesia shows us some of the ways out from Totemism, exogamy, and descent in the female line. It also shows us, what Australia does not, ghost worship: most prominently in Saa, where, with descent in the male line, and hereditary chiefship, eleven generations of ancestors are remembered, 'by the invocation of their successive names in sacrifices.'248 This is a solitary case of such genealogical knowledge among Melanesians, as distinct from Polynesians. It is made possible by the sacrifices to the ancestors. Now, in Australia, there are no such sacrifices. Without them ancestors among low savages cannot be remembered, and could not hand down, as an hereditary totem, the animal or other object which is their 'soul-box,' or the vehicle of the ancestral soul after death. There appears to myself to exist, in Melanesia, a notable tendency to adore, nay, almost to deify, a dead man, as a tindalo. Dr. Codrington cites, from Bishop Selwyn, a case in which a renowned brave man was slain in action. A house, or shrine, was built over his head, and he was canonised, or made a tindalo.

His claims to sanctity were automatically certified by canoe tilting, in principle like our table tilting. The men in the canoe cease paddling, 'in a quiet place,' and, when the canoe begins to tilt, they call over a roll of names of tindalos (human ghosts). At the name of the dead warrior,'the canoe shook again.' A successful raid followed, a new shrine was built for the warrior, and fish and food were sacrificed to him. By this means a great man's memory is, now and then, contrary to general custom, kept green in this region of Melanesia. Occasionally he seems to be on the way towards godship, as a departmental deity, perhaps as god of war.249 Pigs are common victims, now, in sacrifice. We do not hear of any 'totem sacrifice,' if ever such a thing anywhere existed. In the case of a tindalo called Manoga, deification seems close at hand. His 'dwelling is the light of setting suns,' or of the dawn: or in high heaven, or in the Pleiades, or Orion's belt. It is a remarkable circumstance that this discarnate spirit is the tindalo or saint of a kema, or exogamous division, one of the six of Florida, and all of the six possess their tindalo, a ghost patron in receipt of sacrifice, as well as their buto, or animal not to be eaten.250