полная версия

полная версияThe Secret of the Totem

This is a very hard saying!

It seems to rest either on Mr. Frazer's opinion that the south tribes of Queensland, and many on the Upper Murray, Paroo, and Barwan rivers are "coastal" ("which is absurd"), or on a failure to take them into account. For these tribes, the Barkinji, Ta-Ta-Thai, Barinji, and the rest, are the least progressive, and "coastal," of course, they are not.

This apparent failure to take into account the most primitive of all the tribes, those on the Murray, Paroo, Darling, Barwan, and other rivers, and to overlook even the more advanced Kamilaroi, is exhibited by Mr. Howitt, whose example Mr. Frazer copies, in the question of Australian religious beliefs.

I quote a passage from Mr. Howitt, which Mr. Frazer re-states in his own words. He defines "the part of Australia in which a belief exists in an anthropomorphic supernatural being, who lives in the sky, and who is supposed to have some kind of influence on the morals of the natives … That part of Australia which I have indicated as the habitat of tribes having that belief" (namely, 'certainly the whole of Victoria and of New South Wales up to the eastern boundaries of the tribes of the Darling River') "is also the area where there has been the advance from group marriage to individual marriage, from descent in the female line to that in the male line; where the primitive organisation under the class system has been more or less replaced by an organisation based on locality – in fact, where those advances have been made to which I have more than once drawn attention in this work."259

This is an unexpected remark!

Mr. Howitt, in fact, has produced all his examples of tribes with descent in the female line, except the Dieri and Urabunna "nations," from the district which he calls "the habitat of tribes in which there has been advance … from descent in the female to that in the male line." Apparently all, and certainly most of the south-eastern tribes described by him who have not made that advance, cherish the belief in the sky-dwelling All Father.

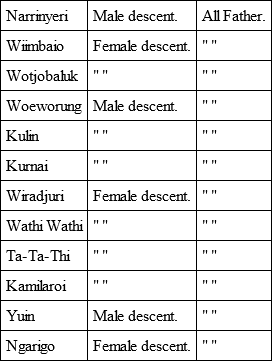

I give examples: —

About other tribes Mr. Howitt's information is rather vague, but, thanks to Mrs. Langloh Parker, we can add: —

Euahlayi – Female descent – All FatherHere, then, we have eight tribes with female descent and the All Father, against five tribes with male descent and the All Father, in the area to which Mr. Howitt assigns "the advance from descent in the female line to that in the male line." The tribes with female descent occupy much the greater part of the southern interior, not of the coastal line, of South-East Australia.

Mr. Frazer puts the case thus, "it can hardly be an accidental coincidence that, as Dr. Howitt has well pointed out, the same regions in which the germs of religion begin to appear have also made some progress towards a higher form of social and family life."260

But though Dr. Howitt has certainly "pointed it out," his statement seems in collision with his own evidence as to the facts. The tribes with female descent and the "germs of religion" occupy the greater part of the area in which he finds "the advance from descent in the female line to that in the male line." He does find that advance, with belief in the All Father, in some tribes, mainly coastal, of his area, but he also finds the belief in the All Father among "nations" and tribes which have not made the "advance" – in the interior. As the northern tribes who have made the "advance" are mainly credited with no All Father, it is clear that the "advance" in social and family life has no connection with the All Father belief. Mr. Howitt, in saying so, overlooks his own collection of evidence. Large tribes and nations, in the region described by him, are in that social organisation which he justly regards as the least advanced of all, yet they have the "germs of religion," which he explains as the results of a social progress which they have not made.

In these circumstances Mr. Howitt might perhaps adopt a large theory of borrowing. The primitive south-east tribes have not borrowed from the remote coastal tribes the usage of male descent; they have not borrowed matrimonial classes from the Kamilaroi. But, nevertheless, they have borrowed, it may be said, their religion from remote coastal tribes. Of course, it is just as easy to guess that the coastal tribes have borrowed their Bunjil All Father from the Kamilaroi Baiame, or the Mulkari of Queensland.

I have not commented on Mr. Frazer's suggestion as to the origin of exogamy. It was the result, he thinks, of a deliberate reformation, and its earliest form was the division of the tribe into the two phratries. "Exogamy was introduced … at first to prevent the marriage of brothers with sisters, and afterwards" (in the matrimonial classes) "to prevent the marriage of parents with children."261 The motive was probably a superstitious fear that such close unions would be harmful, in some way, "to the persons immediately concerned," according to "a savage superstition to which we have lost the clue." I made the same suggestion in Custom and Myth (1884). I added, however, that totemic exogamy might be only one aspect of the general totem tabu on eating, killing, or touching, &c., an object of the totem name. We seem to have found the clue to that superstition, including the blood tabu, emphasised by Dr. Durkheim. But, on this showing, the animal patrons of phratries and totem kins, with their "religion," are among the causes of exogamy, while some unknown superstition, in Mr. Frazer's system, may have been the cause. As we have a known superstition, of origin already explained, it seems unnecessary to suppose an unknown superstition.

Again, if the reformers knew who were brothers and sisters, how can they have been promiscuous? Further, the phratriac prohibition includes vast numbers of persons who are not brothers and sisters, except in the phratry. Sires could prohibit unions of brothers and sisters, each in his own hearth circle; the phratriac prohibition is much more sweeping, so is the matrimonial class prohibition. Once more, parent with child unions do not occur among primitive tribes which have no matrimonial classes at all.

For these reasons Mr. Frazer's system does not recommend itself at least to persons who cherish a different theory.

He may, perhaps, explain the Kaitish usage, in which totems, though not hereditary but acquired in the Arunta manner, remain practically exogamous, by suggesting that the Kaitish are imitating the totemic exogamy of the rest of the savage world. But this hardly accounts for the fact that, among the Arunta, certain totems greatly preponderate in one, and another set of totems in the other exogamous moiety of the tribe. These facts indicate that the Arunta system is relatively recent, and has not yet overcome among the Kaitish the old rule of totemic exogamy. Mr. Frazer, too, as has been said, does not touch on the concomitance of stone churinga nanja with the Arunta system of acquiring totems.

APPENDIX

SOME AMERICAN THEORIES OF TOTEMISM

With some American theories of the origin of totemism, I find it extremely difficult to deal. They ought not to be neglected, that were disrespectful to the valued labours of the school of the American "Bureau of Ethnology." But the expositions are scattered in numerous Reports, and are scarcely focussed with distinctness. Again, the terminology of American inquirers, the technical words which they use, differ from those which we employ. That fact would be unimportant if they employed their technical terms consistently. Unluckily this is not their practice. The terms "clan," "gens," and "phratry" are by them used with bewildering inconsistency, and are often interchangeable. When "clan" or gens, means, now (i) a collection of gentes, or (2) of families, or (3) of phratries, and again (4) "clan" means a totem kin with female descent; and again (5) a village community; while a phratry may be (1) an exogamous moiety of a tribe, or (2) a "family," or (3) a magical society; and a gens may be (1) a clan, or (2) a "family," or (3) an aggregate of families, or (4) a totem kin with male descent, or (5) a magical society, while "tribal" and "sub-tribal divisions" are vaguely spoken of – the European student is apt to be puzzled! All these varieties of terminology occur too frequently in the otherwise most praiseworthy works of some of the American School of Anthropologists. I had collected the examples, but to give them at length would occupy considerable space, and the facts are only too apparent to every reader.262

Once more, and this point is of essential importance, the recent writers on totemism in America dwell mainly on the institution as found among the tribes of the north-west coast of the States and of British Columbia. These tribes are so advanced in material civilisation that they dwell in village settlements. They have a system of credit which looks like a satirical parody of the credit system of the civilised world. In some tribes there is a regular organisation by ranks, noblesse depending on ancestral wealth.

It seems sanguine to look for the origins of totemism among tribes so advanced in material culture. The origin of totemism lies far behind the lowest savagery of Australia. It is found in a more primitive form among the southern and eastern than in most of the north-western American tribes, but the north-western are chiefly studied, for example, by Mr. Hill-Tout, and by Dr. Boas. A new difficulty is caused by the alleged intermixture of tribes in very different states of social organisation. That intermixture, if I understand Mr. Hill-Tout, causes some borrowing of institutions among tribes of different languages, and different degrees of culture, in the west of British Columbia and the adjacent territories. We find, in the north, the primitive Australian type of organisation (Thlinket tribe), with phratries, totems, and descent in the female line. South of these are the Kwakiutl, with descent wavering in a curious fashion between the male and female systems. Further south are the Salish tribes, who have evolved something like the modern family, reckoning on both sides of the house. I, with Mr. McGee of the United States Bureau of Ethnology, suppose the Kwakiutl to be moving from the female to the male line of descent. In the opinions of Mr. Hill-Tout and Dr. Boas, they are moving from the advanced Salish to the primitive Thlinket system, under the influence of their primitive neighbours. It is not for me to decide this question. But it is unprecedented to find tribes with male reverting to female reckoning of descent

Next, Mr. Hill-Tout employs "totem" in various senses. As totems he reckons (1) the sacred animals of the tribe; (2) of the religious or magical societies (containing persons of many totems of descent); (3) of the individual and (4) the hereditary totems of the kin. All these, our author says, are, by their original concept, Guardian Spirits. All such protective animals, plants, or other objects, which patronise and give names to individuals, or kins, or tribes, or societies, are "totems," in the opinion of the late Major Powell, and the "American School," and are essentially "guardian spirits." All are derived by the American theory263 from the manitu, or guardian, of some individual to whom the animal or other object has been revealed in an inspired dream or otherwise. The object became hereditary in the family of that man, descended to his offspring, or, in early societies with reckoning in the female line, to the offspring of his sisters (this is Mr. Hill-Tout's theory), and so became the hereditary totem of a kin, while men of various totem kins unite in religious societies with society "totems" suggested by dreams. These communities may or may not be exogamous, they may even be endogamous. By the friends of this theory the association of exogamy with hereditary kin-totemism is regarded as "accidental," rather than essential.

Using the word "totem" in this wide sense, or in these many senses, which are not ours, it is plain that a man and woman who chance to have the same "personal totem," (i) or belong to the same religious society with its "totem," (i) or to the same local tribe with its "totem," (3) may marry, and, by this way of looking at the matter, "totems" do permit marriage within the totem, and are not exogamous. But we, for our part (like Mr. E. B. Tylor, and M. Van Gennep264), call none of these personal, tribal, or society sacred animals "totems." That term we reserve for the hereditary totem of the exogamous kin. Thus it is not easy, it is almost impossible, for us to argue with Mr. Hill-Tout, as we and he use the term "totem" in utterly different senses.

On his theory there are all sorts of "totems," belonging to individuals and to various kinds of associations. The totems hereditary in the kins when they are exogamous, are exogamous (on Mr. Hill-Tout's theory) because the kins, in certain cases, made a treaty of alliance and intermarriage with other kins for purely political purposes. They might have made such treaties, and become exogamous, though they had no totems, no name-giving animals; and they might have had name-giving animals, and yet not made such treaties involving exogamy. Thus totemic exogamy is, on this theory, a mere accident: the totem has nothing to do with the exogamous rule.

Mr. Hill-Tout writes to me, "The totem groups are exogamous not because of their common totem, but because of blood relationship. It is the blood-tie265 that bans marriage within the totem group, not the common totem. That exogamy and the totem group with female descent go together is accidental, and follows from the fact that the totem group is always, in Indian theory at least, blood related. Where I believe you err is in regarding exogamy as the essential feature of totemism. I cannot so regard it. To me it is secondary, and becomes the bar to marriage only because it marks kinship by blood, which is the real bar, however it may have arisen, and from whatever causes."

Here I am obliged to differ from Mr. Hill-Tout. I know no instance in which a tribe with female kin (the most primitive confessedly), and with hereditary totems, is not exogamous. Exogamy, then, if an accident, must be called an inseparable accident of totemism, with female descent, till cases to the contrary are proved to exist. Mr. Hill-Tout cites the Arunta case: totems among the Arunta are not exogamous. But of that argument we have disposed (see Chapter IV.), and it need no longer trouble us.

Again, it is not possible to agree with Mr. Hill-Tout when he writes, "It is the blood-tie that bars marriage within the totem group, not the common totem." The totem does not by its law prevent marriages of blood kin. A man, as far as totem law goes, may marry his daughter by blood, a brother may marry his sister on the father's side (with female descent), and a man may not marry a woman from a thousand miles away if she is of his totem, though she is not of his blood. It is not the real blood-tie itself, but the blood-tie as defined and sanctioned by the totem, that is not to be violated by marriage within it.

To return to the theory that totems are tutelary spirits in animal or other natural forms. A man may have a spirit guardian in animal form, that is his "totem," on the theory. He may transmit it to his descendants, and then it is their "totem"; or his sisters may adopt it, and hand it down in the female line, and then it is the totem of his nephews and nieces for ever; or the man may not transmit it at all. Usually, it is manifest, he did not transmit it; for there must have been countless species of animal protectors of individuals, but tribes in America have very few totems. If a man does transmit his animal protector, his descendants, lineal or collateral, may become exogamous, on the theory, by making other kins treaties of intermarriage to secure political alliances; or they may not, just as taste or chance direct. All the while, every "totem" of every sort, hereditary or not, is, on this theory, a guardian spirit. That spiritual entity is the essence of totemism, exogamy is an accident – according to Mr. Hill-Tout.

Such is his theory. It is, perhaps, the result of studying the North-West American Sulia, or "personal totem" answering to the nyarongs of Borneo, the naguals of the Southern American tribes, the yunbeai of the Euahlayi of New South Wales, and the "Bush Souls" of West Africa. All of these are, as the Ibans of Borneo imply in the term nyarong, "spirit helpers," in animal or material form. Some tribes call genuine totems by one name, but call animal familiars of an individual by another name. Budjan, among the Wiradjuri, stands both for a man's totem, and for the animal familiar which, rduring apparently hypnotic suggestion," he receives on being initiated.266 Among the Ibans (but not among the few Australian tribes which have yunbeai), the spirit helper may befriend the great-grandchildren of its original protégé.267

But in no case recorded does this nyarong become the hereditary totem of an exogamous kin.

The "spirit helper" does not do that, nor am I aware, on the other hand, that the hereditary totem of an exogamous kin is ever, or anywhere, regarded as a "tutelary spirit." No such idea has ever been found in Australia. Again, if I understand Dr. Boas, among his north-western tribes, such as the Thlinket, who have female descent and hereditary exogamous totems, the totem is no more regarded as a tutelary spirit than it is among the Australians. Of the Kwakiutl he says, "The manitu" (that is, the individual's tutelary spirit) "was acquired by a mythical ancestor, and the connection has become so slight, in many cases, that the tutelary genius of the clan has degenerated into a crest."

That the "crest" or totem mark was originally a "tutelary genius" among the Thlinket, seems to be merely the hypothesis of Dr. Boas. Even among the Kwakiutl, in their transitional state, the totem mark now is "in many cases a crest." "This degeneration" (from spirit to crest), our author writes, "I take to be due to the influence of the northern totemism," such as that of the Thlinket.268 Thus the Thlinket, totemic on Australian primitive lines, do not regard their hereditary exogamous totems as "tutelary spirits."269 No more do the Australians, nor the many American totemists who claim descent from the animal which is their totem.270

The tutelary spirit and the true totem, in my opinion, are utterly different things. The American theory that all things (their name is legion) called "totems" by the American School are, in origin and essence, tutelary spirits, is thus countered by the fact that the Australian tribes do not regard their hereditary totems as such; nor do many American tribes, even when they are familiar with the idea of the tutelary spirits of individuals. The Euahlayi, in Australia for instance, call tutelary spirits yunbeai; hereditary totems they call by a separate name, Dhe.271

The theory that the hereditary totem of the exogamous kin is the "spirit helper" or "tutelary genius," acquired by and transmitted by an actual ancestor, cannot be proved, for many reasons. We know plenty of tribes in which the individual has a "spirit helper," we know none in which he bequeaths it as the totem of an exogamous kin.

Again we find, (1) in Australia, tribes with hereditary totems, but with no "personal totems," as far as our knowledge goes. Whence, then, came Australian hereditary totems? Next, (2) we find tribes with both hereditary and "personal totems," but the "personal totems" are never hereditable. The "spirit helpers," where they do occur in Australia, are either the familiars of wizards (like the witch's cat or hare), or are given by wizards to others.272 Next, (3) we find, in Africa and elsewhere, tribes with "personal totems," but with no hereditary totems. Why not? For these reasons, the theory that hereditary kin-totems are personal tutelary spirits become hereditary, seems a highly improbable conjecture. If it were right, genuine totemism, with exogamy, might arise in any savage society where "personal totems" flourish. But we never find totemism, with exogamy, just coming into existence.

To sum up the discussion as far as it has gone, Mr. Hill-Tout had maintained (1) that the concept of a ghostly helper is the basis of all his varieties of so-called "totems." I have replied that the idea of a tutelary spirit makes no part of the Australian, or usually of the American "concepts" about the hereditary totems. This is matter of certainty.

Mr. Hill-Tout next argues that hereditary totems are only "personal totems" become hereditary, which may happen, he says, in almost any stage of savage society. I have replied, "not plus the totemic law of exogamy," and he has answered (3) that the law is casual, and may or may not accompany a system of totemic kindred, instancing the Arunta, as a negative example. In answer, I have shown that the Arunta case is not to the point, that it is an isolated "sport."

I have also remarked frequently, in previous works, that under the primitive method of reckoning descent in the female line, an individual male cannot bequeath his personal protective animal as a kin-name to his descendants, so that the hereditary totem of the kin cannot have originated in that way. Mr. Hill-Tout answers that it can, and does, originate in that way – a male founder of a family can, and does, found it by bequeathing his personal protective animal to the descendants of his sisters, so that it henceforth passes in the female line. I quote his reply to my contention that this is not found to occur.273

"The main objection brought against this view of the matter by Mr. Andrew Lang and others is that the personal totem is not transmissible or hereditable. But is not this objection contrary to the facts of the case? We have abundant evidence to show that the personal totem is transmissible and hereditable. Even among tribes like the Thompson, where it was the custom for every one of both sexes to acquire a guardian spirit at the period of puberty, we find the totem is in some instances hereditable. Teit says, in his detailed account of the guardian spirits of the Thompson Indians, that 'the totems of the shamans274 are sometimes inherited directly from the parents'; and among those tribes where individual totemism is not so prevalent, as, for instance, among the coast tribes of British Columbia, the personal totem of a chief or other prominent individual, more particularly if that totem has been acquired by means other than the usual dream or vision, such as a personal encounter with the object in the forest or in the mountains, is commonly inherited and owned by his or her posterity. It is but a few weeks ago that I made a special inquiry into this subject among some of the Halkomelem tribes of the Lower Fraser. 'Dr. George,' a noted shaman275 of the Tcil'Qe'Ek, related to me the manner in which his grandfather had acquired their family totem,276 the Bear; and made it perfectly clear that the Bear had been ever since the totem of all his grandfather's descendants. The important totem of the Sqoiàqî277 which has members in a dozen different tribes of the coast and Lower Fraser Salish, is another case in point. It matters little to us how the first possessor of the totem acquired it. We may utterly disregard the account of its origin as given by the Indians themselves, the main fact for us is, that between a certain object or being and a body of people, certain mysterious relations have been established, identical with those existing between the individual and his personal totem; and that these people trace their descent from and are the lineal descendants of the man or woman who first acquired the totem. Here is evidence direct and ample of the hereditability of the individual totem, and American data abound in it."

All these things occur under the system of male kinship. Even if the "personal totem" of a chief or shaman is adopted by his offspring, it does not affect my argument, nor are the bearers of the badge thus inherited said to constitute an exogamous kin.278 If they do not, the affair is not, in my sense, "totemic" at all. We should be dealing not with totemism but with heraldry, as when a man of the name of Lion obtains a lion as his crest, and transmits it to his family. Meanwhile I do not see "evidence direct and ample," or a shred of evidence, that a man's familiar animal is borrowed by his sisters, and handed on to their children.