полная версия

полная версияA History of Lancashire

Many of the Lancashire gentry, hoping to again establish the Catholic religion, openly espoused the cause of Mary, Queen of Scots. The Bishop of Carlisle, writing to the Earl of Essex in 1570, gives an account of the state of Lancashire in that year; he writes: “Before my coming to York, Sir John Atherton arrived there from Lancashire, where he long resided, and not being able to come to my house through infirmities, he sent to my father and declared to him how all things in Lancashire savoured of rebellion; what provision of men, armour, horses and munition was made there; what assemblies of 500 or 600 at a time; what wanton talk of invasion by the Spaniards; and how in most places the people fell from their obedience and utterly refused to attend divine service in the English tongue. How since Felton set up his bull so the greatest there never came to any service, nor suffered any to be said in their houses, but openly entertained Louvainists massers with their bulls.”197 And the same year the Bishop wrote to Sir William Cecil (afterwards Baron Burleigh), that in Lancashire the people were falling from religion altogether, and were returning to “popery and refused to come to church.”

Ten years later things seem little improved, as Sir Edmund Trafford writes in 1580 to the Earl of Leicester, informing him that the state of the county was “lamentable to behold, considering the great disorder thereof in matters of religion, masses being said in several places.” And he winds up with a request that the Government will cause the offenders to be rigorously dealt with.198 Possibly in reply to this appeal a Royal Ecclesiastical Commission was now appointed, consisting of the Bishop of Chester, Lord Derby and others, which was to bring the offenders “to more dutiful minds;”199 and about the same time an Act was passed by which absentees from church for a month were to be liable to a penalty of £20. A contemporary Roman Catholic writer, commenting upon the appointment of Sir Edmund Trafford as Sheriff of Lancashire, describes him as a man “so thoroughly imbued with the perfidy of Calvin and the phrensy of Beza, that it might be said he was merely waiting for this very opportunity of in every way pursuing with insult all that professed the Catholic religion, and despoiling them of their property. For the furious hate of this inhuman wretch was all the more fiercely stirred by the fact that he saw offered to him such a prospect of increasing his slender means out of the property of the Catholics, and of adorning his house with the various articles of furniture filched from their houses.” He then goes on in the same strain to describe the manner in which the Sheriff’s officers took possession of Rossall, and expelled therefrom the widowed mother and sisters of Cardinal Allen.200 The persecution in Lancashire now became more severe, and very few of the old families adhering to the unreformed religion escaped punishment. Amongst those who were imprisoned were Sir John Southworth, Lady Egerton, James Labourne, John Townley, Sir Thomas Hesketh, Bartholomew Hesketh and Richard Massey.

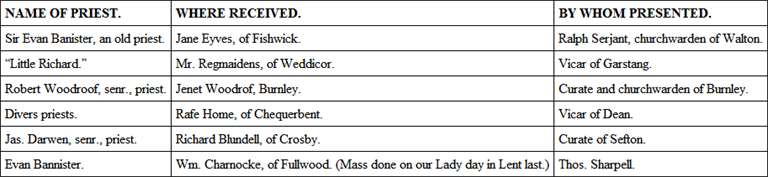

In 1582 the prisoners, on the ground of recusancy, were ordered to be sent to the New Fleet prison in Manchester, instead of, as heretofore, to Chester Castle. At this time numerous amateur detectives seem to have made out lists of recusants and forwarded the same to the Government officials, so that no man knew who was his accuser; but once his name got down on the list, persecution and fine or imprisonment invariably followed. In 1585 the sanguinary law against Jesuits, seminary priests, and others was enacted, and by it all such were ordered at once to quit the country, and anyone harbouring them was to be adjudged guilty of high–treason. This brought a new crime into existence, and many Lancashire people became the victims. Priest–harbouring was soon amongst the most prolific causes of arrest and imprisonment. As samples of the working of this Act in Lancashire, the following are selected from a long list:

The following year (1586–7) no less than 128 gentlemen in various parts of the country were in custody for recusancy, amongst whom were several from this county, who were released on giving bond to yield themselves up on ten days’ notice.

In 1591 a report was sent to the Council, from which it appears that the Lancashire commission had made “small reformation,” and that, notwithstanding the rigour of the law, the churches were still empty, and there were still “multitudes of bastards and drunkards”; in fact, the county was in a worse state than ever; the people, it is added, “lack instruction, for the preachers are few: most of the parsons are unlearned, many of them non–resident, and divers unlearned daily [are] admitted into very good benefices.” But even a greater evil is yet added, for the young “are for the most part trained up by such as profess Papistry. The proclamation for apprehension of seminaries, Jesuits and Mass priests, and for calling home children from parts beyond the sea” is not executed, neither are the instructions to the justices to summon before them “all parsons, vicars, churchwardens and sworn men,” and to examine them on oath how the statutes of 1 and 25 Elizabeth, as to resorting to churches, are obeyed. It is further reported that some of “the coroners and justices and their families do not frequent church, and many have not communicated at the Lord’s Supper since the beginning of her Majesty’s reign.” Some of the clergy have “refrained from preaching for lack of auditors, and people swarm in the streets and the ale–houses during divine service time,” and many churches have only present “the curate and the clerk,” and “open markets are kept during service time,” and “there are about many lusty vagabonds.” Marriages and christenings are celebrated in holes and corners by seminary and other priests. Cock–fights and other games are tolerated on Sundays and holidays during service, at which ofttimes are present justices of the peace, and even some of the ecclesiastical commissioners. The report concludes by stating that Yorkshire and the other adjoining counties cannot “be kept in order so long as Lancashire remains unreformed.”

Another report of about the same date, made by several of the Lancashire clergy,201 confirms this account; they state that Popish fasts and festivals were everywhere observed, and that “crosses in the streets and waies, devoutly garnished, were plentiful, and that wakes, ale, greenes, May games, rushbearings, bearbaits, doveales, etc.,” were all exercised on the Sabbath, and that of the number of those who came to church many do more harm than good by their “crossinge and knockinges of theire breste and sometimes with beads closely handled” (i. e., partly concealed), and that at marriages they brought “the parties to and from churche with piping, and spend the whole Sabbothe in daunsinge,” and that the churches generally were in a ruinous condition, being “unrepaired and unfurnished,” whilst the “churches of ease (which were three times as many as the parish churches)” were many of them without curates, and in consequence were growing into “utter ruin and desolation.” This report, which has a strong Puritanical tone about it, was signed by a Fellow of the Manchester Collegiate Church, the rectors of Bury, Wigan, Warrington and Middleton, the vicars of Poulton–in–the–Fylde, Kirkham and Rochdale, and other clergy.

One of the signatories of this document knew well the truth of at all events part of the statement, for in his own parish (Kirkham) was situated the chapel of Singleton, the curate of which in 1578 had been presented because he performed no services, kept no house, did not relieve the poor, nor was he diligent in visiting the sick, he failed to teach the catechism, preached no sermons, churched fornicators without penance, and, to crown his offences, he made “a dunge hill in the chapel yeard and kept a typling hous and a nowty woman in it.”202

At this date it was customary at most of the Lancashire parish churches to ring the curfew at seven o’clock in the evening from All Hallows’ Day (October 31) to Candlemas Day (the Purification of the Virgin), February 2; another duty of the sexton was to whip the dogs out of church. The curfew was tolled in some of the churches up to quite a recent date. Thomas Heneage, Chancellor of the duchy, gave testimony in 1599 that in consequence of the smallness of many of the livings in the county, and the fact that the parsonages were in private hands, there were “few or no incumbents of learning or credit,” and the priests were drawing even those from their duty.

The report led to the ordering of salaries to be paid to certain preachers (afterwards called King’s preachers), who were to deliver sermons in various parts of the county. In the commencement of the seventeenth century things became somewhat more settled, but still the agents of the Government often met with great opposition in their efforts to carry out their instructions, and this continued to the very end of the reign of Elizabeth, for in 1602–3 the Bishop of London complains that “in Lancashire and those parts, recusants stand not in fear by reason of the great multitude there is of them.” Likewise he had heard it “reported publicly that amongst them they of that country had beaten divers pursuivants extremely, and made them vow and swear that they would never meddle with any recusants more. And one pursuivant in particular, to eat his warrant and vow never to trouble them nor any recusants more.”203 On the accession of James to the throne, both the Catholics and Puritans hoped to obtain some redress, or at any rate more freedom from oppression and persecution; but instead of this hope being realized, they soon heard of new penal regulations being issued which in no way encouraged either party. The Puritans in Lancashire were offended by the issue of the “Book of Sports” (see p. 123), and the Catholics were still obliged to resort to all kinds of strategy to avoid arrest and imprisonment or fines. Nor did either of the two great religious factions receive much better treatment under Charles I., in whose reign two (if not more) Catholics suffered for their religion the extreme penalty of the law at Lancaster. One of these was Edmund Arrowsmith, a priest of the Order of Jesus; he was hung, and afterwards beheaded and dismembered. This was in 1628. At Bryn Hall (lately pulled down), until very recently, was preserved what was said to be the hand of Father Arrowsmith, the tradition being that just before his death he requested his spiritual attendant to cut off his right hand, which should then have the power to work cures on those who were touched by it and had the necessary amount of faith. Accounts of the miraculous cures worked by this hand were printed as recently as 1737.204

It will here be a suitable place to notice briefly a peculiar form of vestry which in the sixteenth century was common in the hundred of Amounderness and recognised as “sworn men.” Preston, Kirkham, Goosnargh, Poulton, St. Michael’s–on–Wyre, Garstang, Lancaster and Ribchester, each had this executive body, though the number varied; but most of the parishes had twenty–four sworn men. The oath taken by these officers was to the effect that they would keep, observe and maintain all ancient customs as far as they agreed with the law of the realm and were for the benefit of the particular parish or chapelry. Their duties were numerous: they levied the rates, elected the parish clerk in some cases, appointed churchwardens, and even laid claim to nominate the vicar, and in a general way they not only looked after the fabric of the church, but regulated its ceremonies and attended to the welfare of the parish. These men were not re–elected annually, as in the case of churchwardens, but, once appointed, they held office for life, unless they left the parish or were disqualified by becoming Nonconformists or other sufficient reason. The best men in the parish often were included in the list, and in many cases sons succeeded fathers for several generations.205

During the years immediately preceding the Civil Wars, Puritanism had gone on increasing, and at the opening of the Long Parliament, in 1640, it was felt that some change in the form of religious worship had become an absolute necessity to meet the clamorous demands heard on all sides. Lancashire, just as it had for long been a stronghold of Catholicism, now became a centre of Puritanism; and for many years to come the intolerant spirit of both parties helped to retard the progress of free religious thought.

Parliament distinctly for some time fostered Puritanism, which ultimately led to the adoption of the Presbyterian form of Church government, which was developed between the years 1643 and 1648. A modern writer206 truly remarks that, “If Puritanism anywhere had scope to live and act, it was here” (in Lancashire); “if anywhere in England it was actually a force, it was in Lancashire. There is no other part of England that can furnish so complete an illustration of the true spirit of this seventeenth–century Puritanism as it was manifested in actual practice, and it is this that gives such a peculiar value to the records of the religious life of the county during the years 1643–60.”

The actual change of Church government did not much affect the county, until the Assembly at Westminster replaced the Book of Common Prayer by the Directory; this was effected on January 3, 1645, when it was sanctioned by Parliament: other orders rapidly followed. Altars, raised Communion–tables, images, pictures, organs, and “all superstitious inscriptions” were soon swept away, and the energies of the Presbyterian party became concentrated against the clergy, the churches, and their endowment. In 1646 the titles of archbishops and bishops were abolished, and their possessions placed in the hands of trustees, and not long afterwards the “title, dignity, function, and office” of dean, sub–dean, and dean and chapter were done away with. Under the Act for providing maintenance of preachers, passed in 1649, the issues of Church livings were employed to pay preachers appointed by Parliament or the presbytery. The Church Survey of the Lancashire parochial districts was begun in June, 1650, and from it we learn the state of each parish through the evidence brought before the commissioners, who had sixteen sittings in the county; they met three times at Manchester, six at Wigan, three at Lancaster, three at Preston, and once at Blackburn. There were then in the county 64207 parish churches, 118 chapels–of–ease, of which no less than 38 were without ministers, chiefly for want of maintenance. All the churches, with one or two exceptions, had curates, pastors, or ministers, as they called themselves. The parishes in many instances were said to be very large, and subdivision was recommended, whilst some of the chapels were so far from the mother church that it was suggested that they should be made into parish churches.

The survey furnishes the names of all the ministers, and their fitness or otherwise for the office they held; as most of them were said to be “godly preaching ministers,” or were “of good lyfe and conversation, but keept not the fast–days appointed by Parliament,” it may safely be inferred that the old vicars and curates had mostly either conformed or been superseded by the then holders of the livings. On September 13, 1646, a petition was sent to both Houses of Parliament, styled “The humble petition of many thousand of the well–affected gentlemen, ministers, freeholders, and other inhabitants of the county palatine of Lancaster.” This petition set forth that, “through the not settling of Church government, schism, error, heresy, profaneness, and blasphemy woefully spread”; separate congregations being “erected and multiplied, sectaries grew insolent, confidently expecting a toleration.” The petitioners then go on in the true spirit of those times to pray that some speedy course should betaken “for suppressing of all separate congregations of Anabaptists, Brownists, heretics, schismatics, blasphemers, and other sectaries” which refused to submit to “discipline and government,” and, further, that such “refusers and members of such congregations” should not only be removed from, but kept out of “all places of public trust.” Shortly after this (October 2, 1646) the county was divided into nine classical presbyteries, as follows:

1. The parishes of Manchester, Prestwich, Oldham, Flixton, Eccles, and Ashton–under–Lyne. The members nominated consisted of eight ministers and seventeen laymen.208

2. The parishes of Bolton, Bury, Middleton, Rochdale, Deane, and Radcliffe. Its members, ten ministers and twenty laymen.

3. The parishes of Whalley, Chipping, and Ribchester. Its members, eight ministers and seventeen laymen.

4. The parishes of Warrington, Winwick, Leigh, Wigan, Holland, and Prescot. Its members, fourteen ministers and twenty–eight laymen.

5. The parishes of Walton, Huyton, Childwall, Sefton, Alcar, North Meols, Halsall, Ormskirk, and Aughton. Its members, fifteen ministers and twenty–three laymen.

6. The parishes of Croston, Leyland, Standish, Ecclestone, Penwortham, Hoole, and Brindle. Its members, six ministers and fourteen laymen.

7. The parishes of Preston, Kirkham, Garstang, and Poulton.209 Its members, six ministers and thirteen laymen.

8. The parishes of Lancaster, Cockerham, Claughton, Melling, Tatham, Tunstall, Whittington, Warton, Bolton–le–Sands, Halton, and Heysham. Its members, eight ministers and eighteen laymen.

9. The parishes of Aldingham, Urswick, Ulverston, Hawkshead, Colton, Dalton, Cartmel, Kirkby, and Pennington. Its members, five ministers and eleven laymen.

The names of all these members have many times been printed. It does not necessarily follow that all the persons nominated as “fit to be of” each classis absolutely acted in that capacity; indeed, it is well known that many refused the office.

These classes at once took upon them the management and control of things ecclesiastical. The Manchester classis first met on February 16, 1646/7, when Richard Heyricke, the Warden of the collegiate church, was appointed Moderator, although he had formerly been one of the warmest supporters of the Church and King; at their second meeting, on March 16, 1646/7, they passed a resolution to the effect that all who preached within the classis who were not members of it were to be called to account, as were also all ministers or others who permitted them so to preach. A considerable part of the time of the successive meetings was taken up by the inquiry into cases of immoral conduct and social scandals affecting the members of the various congregations: candidates for the ministry were examined by the Presbyters of each classis, and, if approved, were duly ordained; and it was also part of their work to see that improper persons were not admitted to the Lord’s Supper.

From two remarkable papers, signed by a large number of the Lancashire ministers, in 1648 and 1649, we gather something of the spirit of the age. One of these is “the Harmonious Consent of the Ministers of the Province within the County–Palatine of Lancaster, etc., in their testimony to the truth of Jesus Christ and to our solemn League and Covenant; as also against the errours, heresies, and blasphemies of these times and the toleration of them”; the other is, “The Paper called the Agreement of the People taken into consideration, and the lawfulness of Subscription to it examined and resolved in the negative, by Ministers of Christ in the Province of Lancaster, etc.” In the “Harmonious Consent”210 toleration is thus dealt with: “We are here led to express with what astonishment and horrour we are struck when we seriously weigh what endeavours are used for the establishing of an universal toleration of all the pernicious errours, blasphemies, and heretical doctrines broached in these times, as if men would not sin fast enough except they were bidden”; such a toleration, it is urged, would be “a giving Satan full liberty to set up his thresholds by God’s thresholds and his posts by God’s posts, his Dagon by God’s Ark”; and further, “it would be putting a sword in a madman’s hand, a cup of poyson into the hand of a child, a letting loose of madmen with firebrands in their hands, an appointing a city of refuge for the devil to fly to, a laying of a stumbling block before the blind, a proclaiming of liberty to the wolves to come into Christ’s fold to prey upon his lambs; a toleration of soul–murther (the greatest murther of all others), and for the establishing whereof damned souls in hel would accurse men on earth.” The petitioners also dreaded “to think what horrid blasphemies would be belched out against God, what vile abominations would be committed, how the duties of nearest relatives would be violated”; they then express their opinion that “the establishing of a toleration would make us to become the abhorring and loathing of all nations,” and after adding the words, “we do detest the forementioned toleration,” they conclude by praying that Parliament may be kept from “being guilty of so great a sin” as the granting of it would be.

This petition was signed by eighty–four ministers who had in their charge the principal parishes in the county. The other paper is quite as rabid in its tone, and bears the signature of nearly as many divines as the “Harmonious Consent.” It sets forth clearly the points at issue, one of which was that it was proposed that “such as profess faith in God by Jesus Christ (however differing in judgement from the doctrine, worship or discipline publiquely held forth) shall not be restrained from, but shall be protected in their profession of their faith and exercise of religion, according to their consciences.” To this proposition the minister of the province of Lancaster exclaims: “Thus all damnable heresies, doctrines of devils, idolatrous, superstitious and abominable religions, that ever have been broached, or practised, or can be devised (if the persons owning them will but profess faith in God by Jesus Christ) are set at liberty in this kingdom; nay, not only granted toleration, but enfranchisement, yea, protection and patronage.”

We now find practically all the churches and chapels in the hands of the Presbyterians, and governed by the various classes, which met periodically at central places. These classes sent delegates to attend the provincial synod which met at Preston twice a year. In little less than three years after the formation of these classes difficulties arose in their working, not only because some places, such as Denton, Salford and Oldham, became disaffected, but in other places several members declined to continue their membership. A great cause of division amongst the various congregations was the conduct of the ministers and elders as to the admission of communicants. Oliver Heywood gives an account of the proceedings on this point at Bolton; he says: “There were two ministers, with whom were associated twelve elders, chosen out of the parish. These sat with the ministers, carried their votes into effect, inquired into the conversation of their neighbours, assembled usually with the ministers when they examined communicants, and though the ministers only examined, yet the elders approved or disapproved. These together made an order that every communicant, as often as he was to partake of the Lord’s Supper, should come to the ruling elders on the Friday before, and request and receive a ticket which he was to deliver up to the elders immediately before his partaking of that ordinance. The ticket was of lead, with a stamp upon it, and the design was that they might know that none intruded themselves without previous permission. The elders went through the congregation and took the tickets from the people, and they had to fetch them again by the next opportunity, which was every month. But this became the occasion of great dissension in the congregations, for several Christians stumbled at it, and refused to come for tickets; yet ventured to sit down, so that when the elders came they had no tickets to give in.”

This state of things was not confined to a single parish, but was widespread, so that in some churches, rather than administer the Sacrament “promiscuously,” the minister declined to administer it at all, and it was in a few places suspended for several years.

Whatever may be said as to the general dogmatical and narrow–minded views of the Lancashire Puritan clergy, they certainly did make great efforts to institute and maintain a high moral tone amongst their flocks. The every–day life of each member was subjected to rigid inquisitorial supervision, and his sins were dealt with in no half–hearted manner, excommunication being a frequent punishment, and even after the offender’s death a funeral sermon was preached and the “occasion improved.” Lancashire is fortunate in having had preserved several of the diaries of her Puritan divines, and these all bear strong testimony to the almost childlike faith which these men held as to the special interference of Providence in the events of everyday life. If a minister was to be tried at Lancaster, God graciously took away the judge by death; if he journeyed to London, the weather was specially arranged to suit; and if anyone was more than ordinarily rebellious against the Church’s discipline and he thereabouts died, it was without the slightest hesitation attributed to a special judgment of God. We have seen with what signs of rejoicing the people of Lancashire (see p. 157) welcomed the restoration of Charles II. The country had got tired of the Commonwealth, and as to the religious feeling, the Episcopalians and Presbyterians were alike glad to have a return to the old form of government; yet the old rancour against Papists was still there, and to it was added a hatred of Anabaptists, Quakers and Independents: against the latter the Puritans were specially exercised.