полная версия

полная версияA History of Lancashire

One curious funeral custom is worth recording. “I went” (writes Stout) “to Preston fair to buy cheese,” the market for cheese being mostly at Garstang and Preston fairs. “At this time we sold much cheese to funerals in the country, from 30 lbs. to 100 lbs. weight, as the deceased was of ability; which was shrived into two or three” (slices or pieces) “in the lb., and one with a penny manchet given to all attendants. And it was customary at Lancaster to give one or two long biscuits, called Naples biscuits, to each attendant, by which from 20 to 100 lbs. was given.” The providing of the penny manchet at the funeral often formed a paragraph in the deceased person’s will, and the doles given to the poor on these occasions were often considerable.

The last Herald’s visitation to the county was made in 1664–65 by Sir William Dugdale, and from it we discover that many old families of the last century have entirely died out, whilst others of more humble origin have succeeded them. The incompleteness of the pedigrees (to say nothing of their glaring inaccuracies) is striking, and one is surprised to find how many families, undoubtedly entitled to bear arms, neglected to enter their descents. The seventeenth century saw the birth of a new order of men in Lancashire, who in many cases rose to opulence and became the founders of what developed into county families; there were the clothiers – they in many instances sprang from the lowest social grade, but by industry and thrift acquired their positions. The clothier purchased the wool (or kept large quantities of sheep), and delivered it to persons who took it to their own homes, and having there made it into cloth, returned it then to their employers. This business was usually carried on in the towns of the county, which were now rapidly springing up, and the demand for the kind of labour required quickly drew workmen from the surrounding agricultural districts. Amongst the most prominent centres for this trade were Manchester, Oldham, Bolton, Rochdale, Ashton, Bury, and Blackburn. In the manorial and other records of this period we find frequent references to “loomhouses,” “bleachouses,” “woolmen,” and “clothmakers.” These pioneers of the wool trade, the clothiers, often lived in large town–houses, adjacent to and communicating with which were their warehouses for the wool and manufactured goods. The contents of one of these establishments is furnished by the inventory attached to the will of Anthony Mosley, of Manchester, clothier, proved at Chester, April 30, 1607. The will itself, after providing for the family of the testator and bestowing several hundred pounds for charitable purposes, concludes with a clause to the effect that the testator’s “walke millers” (i. e., fullers) shall each have a cloak of 10 or 11 shillings a yard; that every one of his servants shall have 40s. each; that at the funeral a dinner shall be provided, and “a dealing to the poor of 2d. a piece”; and finally that the parson who shall make the funeral sermon is to be rewarded with 20s. for his pains. The dwelling–house consisted of the hall, the parlour, and the kitchen, with chambers over them; also a chamber over the warehouse, a brewhouse, a “bolting–chamber,”161 an upper loft, and cellars. The stock of cloth in the warehouse was valued at £255, and the stock at various fulling–mills was estimated at another £740, whilst the various trade debts owing to the deceased amounted to £1,260. The household effects are not given in detail, but are given as “household stuffe and cloth,” and valued at nearly £600, beside £22 of plate. In 1613 there was a heavy decline in the wool trade, to remedy which a Royal Commission was appointed, and subsequently Acts of Parliament passed to remove the impost on cloth, which had been put on by the Merchant Adventurers’ Company, who for some years had an almost complete monopoly of dyeing cloth. The establishment of a free trade in dyeing once more revived the trade, and dyers were found in all our Lancashire towns where woollen cloth was manufactured, and alongside them were found fulling, or, as they were then called, walk mills. Coal, ironstone, and flags where obtainable also now began to find a ready market. Towards the close of the century the making of fustian and other so–called cotton162 goods, which had almost been confined to Manchester, began rapidly to be taken up by the surrounding towns, one of the first of these being Bolton.

Lancashire had not yet established a printing–press,163 though booksellers and stationers were not unknown in the larger towns; and a fair number of authors from this county had furnished materials for the printers of the Metropolis, amongst whom were Isaac Ambrose, Vicar of Preston and Garstang; John Angier, pastor of Denton; Nehemiah Barnet, minister of Lancaster; William Bell, minister at Huyton; Seth Bushell, Vicar of Preston; Henry Pigott, Vicar of Rochdale; Charles Earl, of Derby; Edward Gee, minister at Eccleston; John Harrison, minister of Ashton–under–Lyne; William Leigh, Vicar of Standish; Charles Herle, Vicar of Winwick; Richard Hollingworth, a Fellow of Manchester College; and Richard Wroe, Warden of Manchester; Joseph Rigby; Alexander Rigby; William Moore, Vicar of Whalley; Jeremiah Horrox, the astronomer; Nathaniel Heywood, Vicar of Ormskirk; and a number of writers for and against Quakers (see Chapter IX.). One reason, perhaps, of this absence of the printing–press was that not until 1695 was the censorship of printed matter swept away.

On the restoration of Charles II., as a reward for faithful services to the House of Stuart during the Civil War, it was intended to establish a new order of knighthood; this intention was ultimately abandoned, but those in Lancashire who were to have been honoured were Thomas Holt, Thomas Greenhalgh, Colonel Kirby, Robert Holt, Edmund Asheton, Christopher Banastre, Francis Anderton, Colonel James Anderton, Roger Nowell, Henry Norris, Thomas Preston, – Farrington, – Fleetwood, John Girlington, William Stanley, Edward Tildesley, Thomas Stanley, Richard Boteler, John Ingleton, and C. Walmesley, all of whom had an estate of the value of at least £1,000.

William III., on his way to Ireland, before the battle of the Boyne, embarked from Liverpool on June 14, 1690, and he probably met with but a poor reception from the Lancashire people, as everywhere in the county the Roman Catholics were dissatisfied at the expulsion of the Stuarts by the House of Orange. The unpopularity of the King gave rise to many plots against him, the last of which was known as the “Lancashire Plot,” which, according to one authority,164 was not only the parent but the companion of all the other conspiracies, and its origin was owing to the politics of James II., who, hoping to regain the crown, concerted with his friends, before his departure for France, that they should raise a ferment in England, and that some trusty person should be commissioned to carry out this scheme.

The person selected for this commission was Dr. Bromfield, who, to suit his purpose, passed himself off as a Quaker,165 and passed rapidly through the North of England to Scotland, sowing the seeds of discontent as he went along. From Scotland he proceeded to Ireland, and then returned to Lancashire, intending to make that county the centre of action. Caryl, Lord Molyneux, had, in 1687, been appointed Lord–Lieutenant of Lancashire in the place of Lord Derby; and it was to his house at Croxteth that Dr. Bromfield first proceeded on his return from Ireland; and here he found at all events a sympathizer, if not an active partisan.

From Croxteth he went to an inn at Rhuddlan, in Flintshire, where he stayed for some time, and soon had a considerable number of visitors. From this place he made frequent visits to Ireland, by this means keeping up a safer communication with the exiled King and his friends in Lancashire. Suspicion having fallen on him, the vessel in which he crossed to Ireland was seized, but with the assistance of the landlord of the inn at Rhuddlan he made his escape and repaired to Ireland, where King James made him a Commissioner of the Mint. The Lancashire Plot included the murder of the King, and Colonel Parker, according to De la Rue, was the person who first propounded this portion of the plot to Lord Melford. Dr. Bromfield now found it absolutely necessary to have an active agent, who was to be at once unscrupulous and trustworthy. Such a man he thought he had secured in John Lunt, an Irishman by birth, but who was successively a labourer at Highgate, a coachman, a licensed victualler at Westminster, and one of King James’s Guards, with a promise of a captaincy. Moreover, he was not a man of good character, as he had been tried for bigamy.

This Lunt, having followed the King to France soon after his abdication, was sent from thence with the rest of the guards to Ireland in May, 1689, and there renewed his acquaintance with Bromfield. Being assured that the people in Lancashire only waited the King’s commission to rise in arms on his behalf and restore him to the throne, he at once undertook to be the bearer of the commission. Meanwhile the conspirators in Lancashire, evidently being eager for the rising, sent over to Ireland Edmund Threlfall, of Ashes, in Goosnargh, to fetch the needful commissions, and accordingly he and two others embarked in a “pink” (i. e., a small ship) called the Lion of Lancaster, and sailed down the Lune by night without any Custom–house certificate. This vessel had been used to fetch cattle from the Isle of Man for the Earl of Derby, and the sailors were led to believe that this was again their destination on this occasion; but Threlfall induced the captain to make for Dublin, where they duly arrived, and having received the commission and obtained a passport from Lord Melford, they re–embarked on board the pink, which, to prevent suspicion, was laden with iron pots and bars and other commodities, and they anchored in the Lune near to Cockerham on the morning of June 13, 1689. Whilst in Dublin, Threlfall and Lunt had met, and had now returned together in the pink, and as soon as she was anchored in the Lune they were put ashore, before the arrival of the Custom–house officers, whose practice and duty it was to go on board every vessel as she entered the harbour. Lunt, with that carelessness which so often distinguishes conspirators, left on board his saddle–bags, which contained some of the commissions, and finding out after he got ashore that he had done so, he asked one of the sailors who was returning with the cock–boat to the ship to bring them after him to Cockerham; but before this could be done the officers came on board, and discovering the papers, set off in pursuit of their owners; but not finding them, they handed the documents over to the authorities.

The discovery of these papers caused considerable excitement, and they were carefully examined by the Earl of Devonshire, the Earl of Macclesfield, the Earl of Scarborough and Lord Wharton, who were all in Manchester on army business, and they recommended that warrants should be issued to apprehend Lunt and Threlfall. In the meantime the two conspirators had taken shelter at Myerscough Lodge, near Preston, where lived Thomas Tyldesley, who was one of the foremost supporters of their cause. Here they divided such of the commissions as they had brought with them, Lunt setting off to deliver those for Lancashire, Cheshire and Staffordshire, whilst Threlfall took those for Yorkshire and Durham.

Lunt afterwards went to London to buy arms and enlist men to be sent to Lancashire. At this time Irishmen came into the county in such numbers as to rouse suspicion, and in October the justices of the peace at the adjourned quarter sessions at Manchester sent a letter to the Secretary of State, in which it was stated that the gaols were full of Irish Roman Catholics, that many others were staying at Popish houses, and that boxes with scarlet cloaks, pistols and swords had been sent from London to Roman Catholic gentlemen now absent from home.

The warrants against Lunt and Threlfall were, no doubt, issued, but it was not until August that an arrest was made, when Lunt and Mr. Abbot, the steward of Lord Molyneux, were apprehended at Coventry when they were returning from London. They were cast into prison as enemies to the King, and soon afterward Charles Cawson, the master of the ship which brought Lunt and Threlfall from Ireland, was arrested on a similar charge. Cawson was taken from Coventry to London, where he gave evidence before the Privy Council as to his taking Threlfall to Ireland, and bringing him and Lunt back, also as to the papers left in the pink at Cockerham. Meanwhile Threlfall, having despatched his business in Yorkshire and Durham, where he assumed the name and title of Captain Brown, and probably not knowing that a warrant had been issued against him, returned home to Goosnargh, where he remained for some time concealed, waiting for a chance to get away to Ireland. Ashes, which had been the home of this family for several generations, was well adapted for a place of concealment, not only from its retired situation, but from its peculiar structure, its centre wall being at least 4 feet thick, and containing two cavities large enough to hide half a dozen men in; add to these advantages that the house was surrounded by a moat, and on every side were sympathizing neighbours.

All things considered, perhaps Threlfall was as safe here as anywhere had he used ordinary caution, but on August 20 (1690) he was surprised near his house by a party of militia, and as he offered to resist, he was killed by a corporal who was one of the party. At the trial in Manchester in 1694, one John Wilson, of Chipping, made a deposition that Threlfall had told him that he had twenty Irishmen ready for his troop, who had been at his house and in the county waiting for several months.

In the February following a deposition was made before the Mayor of Evesham, in Worcestershire, that divers persons in that neighbourhood had received commissions from King James to raise two regiments of horse, two of dragoons, and three of foot for Lancashire, and that in various places were hidden arms, etc., especially in the houses of Mr. Blundell, of Ince, and John Holland, of Prescot; and further, that the deponent had seen and heard read a letter from the late Queen in the hand of Lord Molyneux’s son, which gave assurance from the French King of assistance in arms and men. This information led to the imprisonment of several leading Lancashire Roman Catholics.

In the May following, Mr. Robert Dodsworth declared on oath to the Lord Chief Justice Holt that the troops in Lancashire were to be joined by the late King’s forces for Ireland, while the French were to land in Cornwall, and the Duke of Berwick was to cause a diversion in Scotland, but that no rising was to take place until the late King landed in Lancashire, which he had promised to do within a month.

John Lunt in November was committed to Newgate, where he was kept for twenty weeks, and then bailed out to appear at the Lancaster Assizes, where he appeared in August, 1690, and was then committed to Lancaster Castle on a charge of high–treason. Here he remained until April, 1691, when he was brought to trial and acquitted, partly because the Custom–house officers were unable to swear to the papers, and partly because Charles Cawson, the master of the ship, had in the meantime fallen sick and died. Lunt, notwithstanding his long imprisonment and narrow escape from the scaffold, appears almost immediately to have set about raising men and collecting arms for the proposed insurrection. The destruction of the French fleet off the Hague on May 20, 1692, dispersed all thoughts of an invasion and for awhile partially arrested the designs of the conspirators.

The progress of the conspiracy was now slow and spasmodic, and was seriously checked in May, 1694, by the arrest and committal to the Tower of Walter Crosby, on whom were found papers containing many details of the proposed insurrection; but more fatal even than this was that Lunt turned traitor, and on June 15, 1694, made a full confession of all he knew to one of the Secretaries of State. This, then, is the Lancashire Plot as given by the Court advocates, who, if they erred at all, would certainly not do so in favour of the conspirators. As far as Lancashire is concerned, the whole matter was at an end, except that the following gentlemen were all tried at Manchester in 1694, viz.: Caryl, Lord Molyneux, Sir William Gerard, Sir Rowland Stanley, Sir Thomas Clifton, William Dicconson, Esq., Philip Langton, Esq., Bartholomew Walmsley, Esq., and Mr. William Blundell.166

It is but fair to add that the various accounts published regarding this so–called Lancashire Plot contain many variations and inconsistencies, and it is no easy matter to decide which of these various writers is correct; a full account of the trials is now, however, in print, to which the curious reader is referred.167 The result of these trials was that the prisoners were acquitted, the witnesses not being considered worthy of credit; but subsequently the House of Commons, by a vote of 133 to 37, resolved that there were grounds for the prosecution of the gentlemen at Manchester, as it appeared that there was a dangerous plot carried on against the King and his Government; this resolution was also confirmed by the House of Lords.

The Lancashire gentlemen at the next assizes prosecuted Lunt and two others, who were the chief witnesses against them, and they were all three convicted of perjury.

During the reigns of James I. and Charles II. several towns applied for and got fresh powers by royal charter; this was the case with Preston and Liverpool and several smaller towns – amongst the latter were Kirkham and Garstang. At a very early period a market was held at Garstang, but it was not incorporated until 1680, when Charles II. granted a charter whereby the inhabitants were declared to be a “body corporate by the name of the Bailiff and burgesses of the Borough of Garstang.” From 1680 to the present time the Bailiff has regularly been elected.

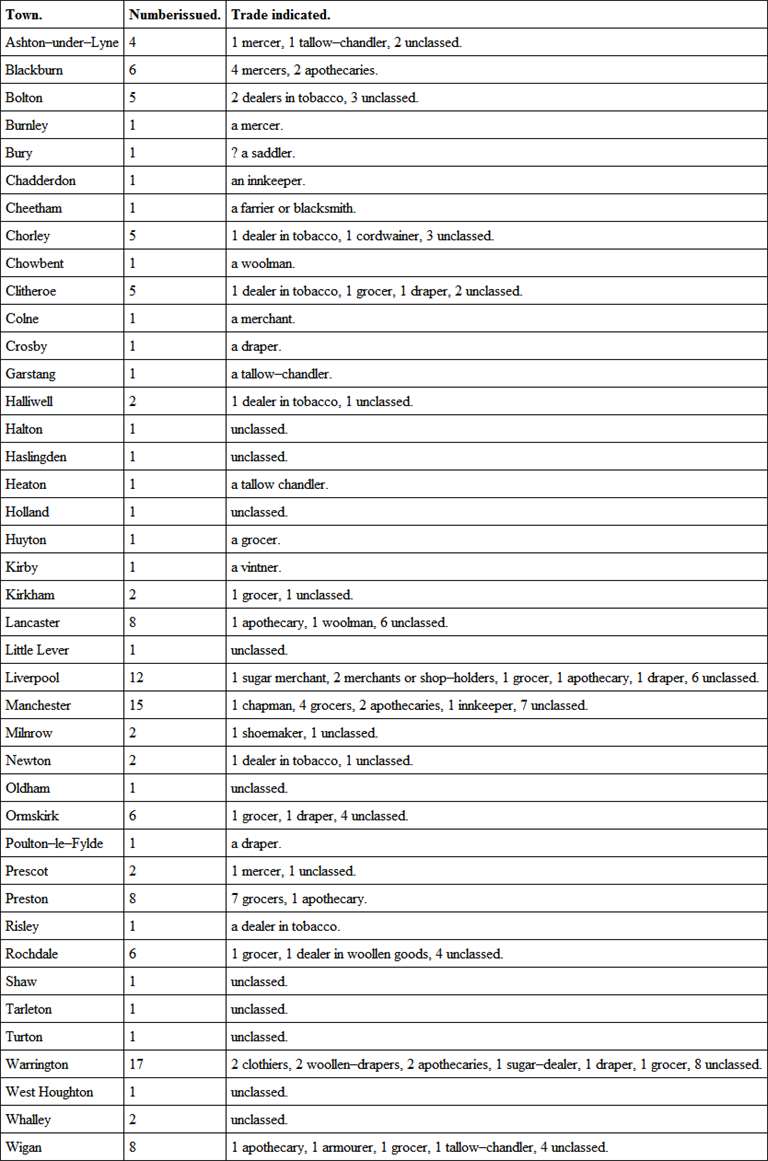

The birth of many new trades in Lancashire dates from the seventeenth century, although many of the national industries were followed here at a much earlier period. We now find numerous references to various trades on the tokens, which were somewhat extensively issued in Lancashire in consequence of the great scarcity of small change shortly after the execution of Charles I. Some of these local tokens were of superior workmanship, and of material calculated to stand the wear to which they were subjected. They represented pennies, half–pennies and farthings.

About 150 varieties of these Lancashire tokens were issued before the close of the seventeenth century,168 some of which indicate the trade followed by the issuer, and thus furnish some clue to the spread of certain industries within the county. A study of them gives the following results:

SEVENTEENTH–CENTURY TOKENS.

Amongst the unclassified several tokens bore religious emblems, such as “the bleeding heart” and the “dove and olive branch”; and the “eagle and child” was a favourite design. Crests or family arms were also often used, but in these cases there is nothing to indicate the occupation of the person who issued the token.

During the century to which the Lancashire plot just recorded formed a fitting close, Lancashire had witnessed many stirring events – the monarchy had been destroyed, the Commonwealth set up, and the rule of kings again established; Roman Catholics had persecuted Protestants, and Puritans had tried their best to repress Roman Catholicism; and in each and every case this county had done its share: if battles were to be fought, the Lancashire lads were in the thick of them; if religious creeds had to be repressed, in their mistaken zeal, there again were the people of this county to the fore. But, notwithstanding wars, plagues, persecutions, insurrections, and a host of minor evils, Lancashire still progressed, her towns increased in number and in size, and her sons were leading the van in all matters of trade, commerce and enterprise. Manchester, Liverpool, Preston, and other large towns were attracting to them men, not only from the surrounding districts, but from all civilized countries; whilst the woollen and other goods manufactured in the county had already obtained a world–wide fame. Amongst other industries introduced during this century was bell–founding, which trade was carried on in Wigan with considerable success as early as 1647, and many church bells in the surrounding districts came from this foundry.

CHAPTER IX

RELIGION

Of the non–Aryan tribes who at some remote period lived in the North of England we do not know sufficient to even conjecture what was their religion, if they had any; but judging from analogy, it may be presumed that they had some kind of belief in a super–human power.

The tribes who next succeeded these rude savages in effecting settlements in this country were all of the Aryan race, and all that we are able to ascertain as to their religious faith is that when Julius landed in Britain he found that the inhabitants were pagans, and followed a mysterious kind of worship known as Druidism, and that their priests were called Druids, and were not only the arbitrators in disputes, but also judges of crime.

One of the tenets of this religion was a belief in the immortality of the soul, and also in its transmigration. As to the nature of their gods we know little or nothing, except that to them were offered human sacrifices, who were sometimes criminals and at other times prisoners of war. Of temples they appear to have had few, but to have performed their mystic rites in the secluded groves of oak which were then found on every side. The Druids were exempt from military service, and were at once priests, lawgivers, and teachers. From the time the Romans penetrated into Northumbria (see p. 15) near the beginning of the fifth century, the religion of the people of that district (which includes, of course, Lancashire) must have undergone a gradual change, as the polytheism of the Romans made itself apparent.

At all their large stations the conquerors erected temples dedicated to their gods, and altars to their various deities were put up in every direction, and thus, no doubt, year by year the influence of the Druidical priesthood diminished, and was probably finally extinguished by the more attractive worship which found favour in imperial Rome.

After the Romans vacated Lancashire, the conversion of Constantine the Great to Christianity (see p. 17) had no doubt some effect upon religious thought even in Northumbria. But long after the Roman Empire became a Christian State, the tribes which were then struggling for supremacy in Britain still adhered to the old pagan worship, and Thor, the god of thunder, Wodin, the god of war, Eostre, the goddess of spring, and a host of others, were numbered amongst their deities. They believed, however, in a future state, as their warriors slain in battle were supposed to inhabit a bright and happy palace called Valhalla. Near the end of the sixth century, King Æthelbert, who ruled in Kent, married the daughter of King Charibert of Paris, and by the terms of her marriage contract she was to be allowed to enjoy the exercise of Christian worship, which she did in a small chapel near Canterbury. With her, from France, came a Frankish Bishop named Liuhard, who was soon followed by a Roman Abbot named Augustine, who came by instructions from Pope Gregory I., accompanied by some forty monks, who were to establish the Christian religion in Kent; they ultimately persuaded the King to be baptized, and this event may be regarded as the foundation of the Christian religion in England. Little by little the new religion spread, and in A.D. 627 Edwin, the King of Northumbria, became a convert through the instrumentality of his wife, who was a daughter of Æthelbert, (see p. 42), and Paulinus, one of the company who came to Britain with Augustine. He had been consecrated to the episcopate by Justus, Archbishop of Canterbury, “in order that he might be to Ethelburga, in her Northern home, what Liuhard had been to her mother in the still heathen Kent.”169 On the authority of Bede, Paulinus was a man of striking appearance, being tall, though slightly stooping, with black hair, but of worn and wasted visage; his nose thin, but curved like an eagle’s beak, and altogether a presence to command respect and veneration.