полная версия

полная версияThe Complete English Tradesman (1839 ed.)

Now, when the poor insolvent has thus surrendered his all, stript himself entirely upon oath, and that oath taken on the penalty of death if it be false, there seems to be a kind of justice due to the bankrupt. He has satisfied the law, and ought to have his liberty given him as a prey, as the text calls it, Jer. xxxix. 18., that he may try the world once again, and see, if possible, to recover his disasters, and get his bread; and it is to be spoken in honour of the justice as well as humanity of that law for delivering bankrupts, that there are more tradesmen recover themselves in this age upon their second endeavours, and by setting up again after they have thus failed and been delivered, than ever were known to do so in ten times the number of years before.

To break, or turn bankrupt, before this, was like a man being taken by the Turks; he seldom recovered liberty to try his fortune again, but frequently languished under the tyranny of the commissioners of bankrupt, or in the Mint, or Friars, or rules of the Fleet, till he wasted the whole estate, and at length his life, and so his debts were all paid at once.

Nor was the case of the creditor much better – I mean as far as respected his debt, for it was very seldom that any considerable dividend was made; on the other hand, large contributions were called for before people knew whether it was likely any thing would be made of the debtor's effects or no, and oftentimes the creditor lost his whole debt, contribution-money and all; so that while the debtor was kept on the rack, as above, being held in suspense by the creditors, or by the commissioners, or both, he spent the creditor's effects, and subsisted at their expense, till, the estate being wasted, the loss fell heavy on every side, and generally most on those who were least able to bear it.

By the present state of things, this evil is indeed altered, and the ruin of the creditor's effects is better prevented; the bankrupt can no more skulk behind the door of the Mint and Rules, and prevent the commissioners' inspection; he must come forth, be examined, give in an account, and surrender himself and effects too, or fly his country, and be seen here no more; and if he does come in, he must give a full account upon oath, on the penalty of his neck.

When the effects are thus surrendered, the commissioners' proceedings are short and summary. The assignees are obliged to make dividends, and not detain the estate in their own hands, as was the case in former days, till sometimes they became bankrupts themselves, so that the creditors are sure now what is put into the hands of the assignees, shall in due time, and without the usual delay, be fairly divided. On the other hand, the poor debtor having honestly discharged his part, and no objection lying against the sincerity of the discovery, has a certificate granted him, which being allowed by the Lord Chancellor, he is a clear man, and may begin the world again, as I have said above.

The creditor, being thus satisfied that the debtor has been faithful, does not answer the end of the act of Parliament, if he declines to assent to the debtor's certificate; nor can any creditor decline it, but on principles which no man cares to own – namely, that of malice, and the highest resentment, which are things a Christian tradesman will not easily act upon.

But I come now to the other part of the case; and this is supposing a debtor fails, and the creditors do not think fit to take out a commission of bankrupt against him, as sometimes is the case, at least, where they see the offers of the debtor are any thing reasonable: my advice in such case is (and I speak it from long experience in such things), that they should always accept the first reasonable proposal of the debtor; and I am not in this talking on the foot of charity and mercy to the debtor, but of the real and undoubted interest of the creditor; nor could I urge it, by such arguments as I shall bring, upon any other foundation; for, if I speak in behalf of the debtor, I must argue commiseration to the miserable, compassion and pity of his family, and a reflection upon the sad changes which human life exposes us all to, and so persuade the creditor to have pity upon not him only, but upon all families in distress.

But, I say, I argue now upon a different foundation, and insist that it is the creditor's true interest, as I hinted before, that if he finds the debtor inclined to be honest, and he sees reason to believe he makes the best offer he can, he should accept the first offer, as being generally the best the debtor can make;24 and, indeed, if the debtor be wise as well as honest, he will make it so, and generally it is found to be so. And there are, indeed, many reasons why the first offers of the debtor are generally the best, and why no commission of bankrupt ordinarily raises so much, notwithstanding all its severities, as the bankrupt offers before it is sued out – not reckoning the time and expense which, notwithstanding all the new methods, attend such things, and are inevitable. For example —

When the debtor, first looking into his affairs, sees the necessity coming upon him of making a stop in trade, and calling his creditors together, the first thought which by the consequence of the thing comes to be considered, is, what offers he can make to them to avoid the having a commission sued out against him, and to which end common prudence, as well as honest principles, move him to make the best offers he can. If he be a man of sense, and, according to what I mentioned in another chapter, has prudently come to a stop in time, before things are run to extremities, and while he has something left to make an offer of that may be considerable, he will seldom meet with creditors so weak or so blind to their own interest not to be willing to end it amicably, rather than to proceed to a commission. And as this is certainly best both for the debtor and the creditor, so, as I argued with the debtor, that he should be wise enough, as well as honest enough, to break betimes, and that it was infinitely best for his own interest, so I must add, on the other hand, to the creditor, that it is always his interest to accept the first offer; and I never knew a commission make more of an estate, where the debtor has been honest, than he (the debtor) proposed to give them without it.

It is true, there are cases where the issuing out a commission may be absolutely necessary. For example —

1. Where the debtor is evidently knavish, and discovers himself to be so, by endeavours to carry off his effects, or alter the property of the estate, confessing judgments, or any the usual ways of fraud, which in such cases are ordinarily practised. Or —

2. Where some creditors, by such judgments, or by attachments of debts, goods delivered, effects made over, or any other way, have gotten some of the estate into their hands, or securities belonging to it, whereby they are in a better state, as to payment, than the rest. Or —

3. Where some people are brought in as creditors, whose debts there is reason to believe are not real, but who place themselves in the room of creditors, in order to receive a dividend for the use of the bankrupt, or some of his family.

In these, and such like cases, a commission is inevitable, and must be taken out; nor does the man merit to be regarded upon the foot of what I call compassion and commiseration at all, but ought to be treated like a rapparee,25 or plunderer, who breaks with a design to make himself whole by the composition; and as many did formerly, who were beggars when they broke, be made rich by the breach. It was to provide against such harpies as these that the act of Parliament was made; and the only remedy against them is a commission, in which the best thing they can do for their creditors is to come in and be examined, give in a false account upon oath, be discovered, convicted of it, and sent to the gallows, as they deserve.

But I am speaking of honest men, the reverse of such thieves as these, who being brought into distress by the ordinary calamities of trade, are willing to do the utmost to satisfy their creditors. When such as these break in the tradesman's debt, let him consider seriously my advice, and he shall find – I might say, he shall always find, but I do affirm, he shall generally find – the first offer the best, and that he will never lose by accepting it. To refuse it is but pushing the debtor to extremities, and running out some of the effects to secure the rest.

First, as to collecting in the debts. Supposing the man is honest, and they can trust him, it is evident no man can make so much of them as the bankrupt. (1.) He knows the circumstances of the debtors, and how best to manage them; he knows who he may best push at, and who best forbear. (2.) He can do it with the least charge; the commissioners or assignees must employ other people, such as attorneys, solicitors, &c., and they are paid dear. The bankrupt sits at home, and by letters into the country, or by visiting them, if in town, can make up every account, answer every objection, judge of every scruple, and, in a word, with ease, compared to what others must do, brings them to comply.

Next, as to selling off a stock of goods. The bankrupt keeps open the shop, disperses or disposes of the goods with advantage; whereas the commission brings all to a sale, or an outcry, or an appraisement, and all sinks the value of the stock; so that the bankrupt can certainly make more of the stock than any other person (always provided he is honest, as I said before), and much more than the creditors can do.

For these reasons, and many others, the bankrupt is able to make a better offer upon his estate than the creditors can expect to raise any other way; and therefore it is their interest always to take the first offer, if they are satisfied there is no fraud in it, and that the man has offered any thing near the extent of what he has left in the world to offer from.

If, then, it be the tradesman's interest to accept of the offer made, there needs no stronger argument to be used with him for the doing it; and nothing is more surprising to me than to see tradesmen, the hardest to come into such compositions, and to push on severities against other tradesmen, as if they were out of the reach of the shocks of fortune themselves, or that it was impossible for them ever to stand in need of the same mercy – the contrary to which I have often seen.

To what purpose should tradesmen push things to extremities against tradesmen, if nothing is to be gotten by it, and if the insolvent tradesman will take proper measures to convince the creditor that his intentions are honest? The law was made for offenders; there needs no law for innocent men: commissions are granted to manage knaves, and hamper and entangle cunning and designing rogues, who seek to raise fortunes out of their creditors' estates, and exalt themselves by their own downfall; they are not designed against honest men, neither, indeed, is there any need of them for such.

Let no man mistake this part, therefore, and think that I am moving tradesmen to be easy and compassionate to rogues and cheats: I am far from it, and have given sufficient testimony of the contrary; having, I assure you, been the only person who actually formed, drew up, and first proposed that very cause to the House of Commons, which made it felony to the bankrupt to give in a false account. It cannot, therefore, be suggested, without manifest injustice, that I would with one breath prompt creditors to be easy to rogues, and to cheating fraudulent bankrupts, and with another make a proposal to have them hanged.

But I move the creditor, on account of his own interest, always to take the first offer, if he sees no palpable fraud in it, or sees no reason to suspect such fraud; and my reason is good, namely, because I believe, as I said before, it is generally the best.

I know there is a new method of putting an end to a tradesman's troubles, by that which was formerly thought the greatest of all troubles; I mean a fraudulent method, or what they call taking out friendly statutes; that is, when tradesmen get statutes taken out against themselves, moved first by some person in kindness to them, and done at the request of the bankrupt himself. This is generally done when the circumstances of the debtor are very low, and he has little or nothing to surrender; and the end is, that the creditors may be obliged to take what there is, and the man may get a full discharge.

This is, indeed, a vile corruption of a good law, and turning the edge of the act against the creditor, not against the debtor; and as he has nothing to surrender, they get little or nothing, and the man is as effectually discharged as if he had paid twenty shillings in the pound; and so he is in a condition to set up again, take fresh credit, break again, and have another commission against him; and so round, as often as he thinks fit. This, indeed, is a fraud upon the act, and shows that all human wisdom is imperfect, that the law wants some repairs, and that it will in time come into consideration again, to be made capable of disappointing the people that intend to make such use of it.

I think there is also wanting a law against twice breaking, and that all second commissions should have some penalty upon the bankrupt, and a third a farther penalty, and if the fourth brought the man to the gallows, it could not be thought hard; for he that has set up and broke, and set up again, and broke again, and the like, a third time, I think merits to be hanged, if he pretends to venture any more.

Most of those crimes against which any laws are published in particular, and which are not capital, have generally an addition of punishment upon a repetition of the crime, and so on – a further punishment to a further repetition. I do not see why it should not be so here; and I doubt not but it would have a good effect upon tradesmen, to make them cautious, and to warn them to avoid such scandalous doings as we see daily practised, breaking three or four, or five times over; and we see instances of some such while I am writing this very chapter.

To such, therefore, I am so far from moving for any favour, either from the law, or from their creditors, that I think the only deficiency of the law at this time is, that it does not reach to inflict a corporal punishment in such a case, but leaves such insolvents to fare well, in common with those whose disasters are greater, and who, being honest and conscientious, merit more favour, but do not often find it.

CHAPTER XIV

OF THE UNFORTUNATE TRADESMAN COMPOUNDING WITH HIS CREDITORS

This is what in the last chapter I called an alternative to that of the fortunate tradesman yielding to accept the composition of his insolvent debtor.

The poor unhappy tradesman, having long laboured in the fire, and finding it is in vain to struggle, but that whether he strives or not strives, he must break; that he does but go backward more and more, and that the longer he holds out, he shall have the less to offer, and be the harder thought of, as well as the harder dealt with – resolves to call his creditors together in time, while there is something considerable to offer them, and while he may have some just account to give of himself, and of his conduct, and that he may not be reproached with having lived on the spoil, and consumed their estates; and thus, being satisfied that the longer he puts the evil day from him, the heavier it will fall when it comes; I say, he resolves to go no farther, and so gets a friend to discourse with and prepare them, and then draws up a state of his case to lay before them.

First, He assures them that he has not wasted his estate, either by vice and immorality, or by expensive and riotous living, luxury, extravagance, and the like.

Secondly, He makes it appear that he has met with great losses, such as he could not avoid; and yet such and so many, that he has not been able to support the weight of them.

Thirdly, That he could have stood it out longer, but that he was sensible if he did, he should but diminish the stock, which, considering his debts, was properly not his own; and that he was resolved not to spend one part of their debts, as he had lost the other.

Fourthly, That he is willing to show them his books, and give up every farthing into their hands, that they might see he acted the part of an honest man to them. And,

Fifthly, That upon his doing so, they will find, that there is in goods and good debts sufficient to pay them fifteen shillings in the pound; after which, and when he has made appear that they have a faithful and just account of every thing laid before them, he hopes they will give him his liberty, that he may try to get his bread, and to maintain his family in the best manner he can; and, if possible, to pay the remainder of the debt.

You see I go all the way upon the suggestion of the poor unfortunate tradesman being critically honest, and showing himself so to the full satisfaction of his creditors; that he shows them distinctly a true state of his case, and offers his books and vouchers to confirm every part of his account.

Upon the suggestion of his being thus sincerely honest, and allowing that the state of his account comes out so well as to pay fifteen shillings in the pound, what and who but a parcel of outrageous hot-headed men would reject such a man? What would they be called, nay, what would they say of themselves, if they should reject such a composition, and should go and take out a commission of bankrupt against such a man? I never knew but one of the like circumstances, that was refused by his creditors; and that one held them out, till they were all glad to accept of half what they said should be first paid them: so may all those be served, who reject such wholesome advice, and the season for accepting a good offer, when it was made them. But I return to the debtor.

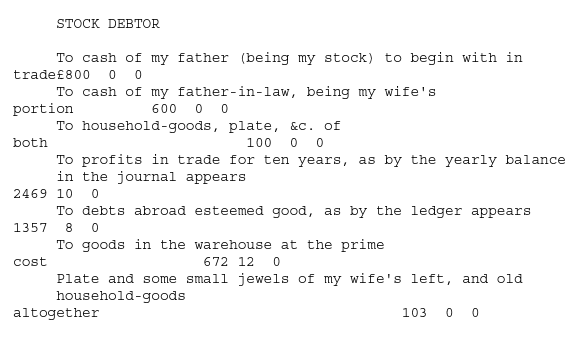

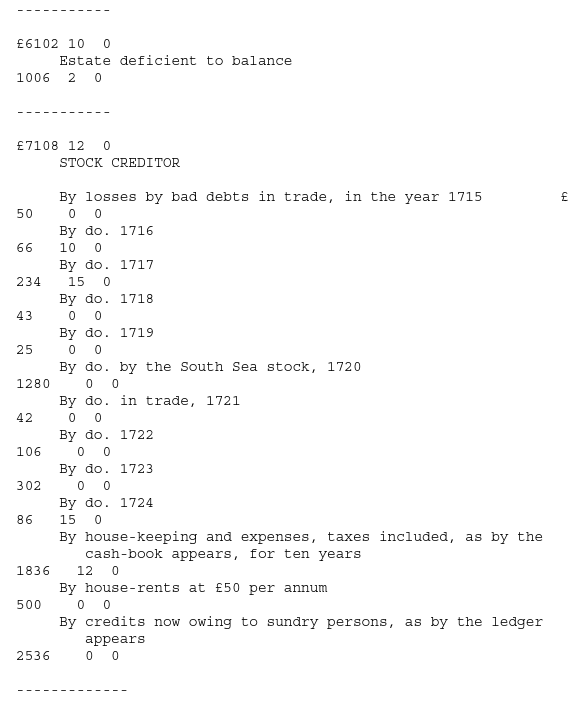

When he looks into his books, he finds himself declined, his own fortune lost, and his creditors' stock in his hands wasted in part, and still wasting, his trade being for want of stock much fallen off, and his family expense and house-rent great; so he draws up the general articles thus: —

This account is drawn out to satisfy himself how his condition stands, and what it is he ought to do: upon the stating which account he sees to his affliction that he has sunk all his own fortune and his wife's, and is a thousand pounds worse than nothing in the world; and that, being obliged to live in the same house for the sake of his business and warehouse, though the rent is too great for him, his trade being declined, his credit sunk, and his family being large, he sees evidently he cannot go on, and that it will only be bringing things from bad to worse; and, above all the rest, being greatly perplexed in his mind that he is spending other people's estates, and that the bread he eats is not his own, he resolves to call his creditors all together, lay before them the true state of his case, and lie at their mercy for the rest.

The account of his present and past fortune standing as it did, and as appears above, the result is as follows, namely, that he has not sufficient to pay all his creditors, though his debts should prove to be all good, and the goods in his warehouse should be fully worth the price they cost, which, being liable to daily contingencies, add to the reasons which pressed him before to make an offer of surrender to his creditors both of his goods and debts, and to give up all into their hands.

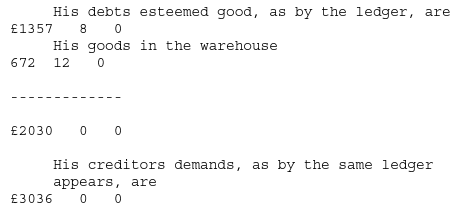

The state of his case, as to his debts and credits, stands as follows: —

This amounts to fifteen shillings in the pound upon all his debts, which, if the creditors please to appoint an assignee or trustee to sell the goods, and collect the debts, he is willing to surrender wholly into their hands, hoping they will, as a favour, give him his household goods, as in the account, for his family use, and his liberty, that he may seek out for some employment to get his bread.

The account being thus clear, the books exactly agreeing, and the man appearing to have acted openly and fairly, the creditors meet, and, after a few consultations, agree to accept his proposals, and the man is a free man immediately, gets fresh credit, opens his shop again, and, doubling his vigilance and application in business, he recovers in a few years, grows rich; then, like an honest man still, he calls all his creditors together again, tells them he does not call them now to a second composition, but to tell them, that having, with God's blessing and his own industry, gotten enough to enable him, he was resolved to pay them the remainder of his old debt; and accordingly does so, to the great joy of his creditors, to his own very great honour, and to the encouragement of all honest men to take the same measures. It is true, this does not often happen, but there have been instances of it, and I could name several within my own knowledge.

But here comes an objection in the way, as follows: It is true this man did very honestly, and his creditors had a great deal of reason to be satisfied with his just dealing with them; but is every man bound thus to strip himself naked? Perhaps this man at the same time had a family to maintain, and had he no debt of justice to them, but to beg his household goods back of them for his poor family, and that as an alms? – and would he not have fared as well, if he had offered his creditors ten shillings in the pound, and took all the rest upon himself, and then he had reserved to himself sufficient to have supported himself in any new undertaking?

The answer to this is short and plain, and no debtor can be at a loss to know his way in it, for otherwise people may make difficulties where there are none; the observing the strict rules of justice and honesty will chalk out his way for him.

The man being deficient in stock, and his estate run out to a thousand pounds worse than nothing by his losses, &c, it is evident all he has left is the proper estate of his creditors, and he has no right to one shilling of it; he owes it them, it is a just debt to them, and he ought to discharge it fairly, by giving up all into their hands, or at least to offer to do so.

But to put the case upon a new foot; as he is obliged to make an offer, as above, to put all his effects, books, and goods into their power, so he may add an alternative to them thus, namely – that if, on the other hand, they do not think proper to take the trouble, or run the risk, of collecting the debts, and selling the goods, which may be difficult, if they will leave it to him to do it, he will undertake to pay them – shillings in the pound, and stand to the hazard both of debts and goods.

Having thus offered the creditors their choice, if they accept the proposal of a certain sum, as sometimes I know they have chosen to do, rather than to have the trouble of making assignees, and run the hazard of the debts, when put into lawyers' hands to collect, and of the goods, to sell them by appraisement; if, I say, they choose this, and offer to discharge the debtor upon payment, suppose it be of ten or twelve shillings in the pound in money, within a certain time, or on giving security for the payment; then, indeed, the debtor is discharged in conscience, and may lawfully and honestly take the remainder as a gift given him by his creditors for undertaking their business, or securing the remainder of their debt to them – I say, the debtor may do this with the utmost satisfaction to his conscience.

But without thus putting it into the creditors' choice, it is a force upon them to offer them any thing less than the utmost farthing that he is able to pay; and particularly to pretend to make an offer as if it were his utmost, and, as is usual, make protestations that it is the most he is able to pay (indeed, every offer of a composition is a kind of protestation that the debtor is not able to pay any more) – I say, to offer thus, and declare he offers as much as possible, and as much as the effects he has left will produce, if his effects are able to produce more, he is then a cheat; for he acts then like one that stands at bay with his creditors, make an offer, and if the creditors do not think fit to accept of it, they must take what methods they think they can take to get more; that is to say, he bids open defiance to their statutes and commissions of bankrupt, and any other proceedings: like a town besieged, which offers to capitulate and to yield upon such and such articles; which implies, that if those articles are not accepted, the garrison will defend themselves to the last extremity, and do all the mischief to the assailants that they can.