Полная версия

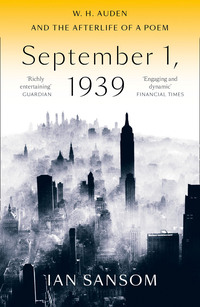

September 1, 1939: A Biography of a Poem

*

This book I began long before I had written or even contemplated writing any of my other books. It was the first – and it may be the last. It may be time to admit defeat, to admit to my own obvious lack of whatever it was that Auden had, which was just about everything. In Auden, one might say – if it didn’t sound so dramatic, if it didn’t sound like I was trying to talk things up by talking myself down – in Auden was my beginning and in Auden is my end.

*

One might, I suppose, console oneself with the knowledge that even some of Auden’s books were not entirely successful: Academic Graffiti, City Without Walls.

But to dwell on the minor faults and failings of the great is hardly a comfort.

It is merely another sign of one’s own inadequacies.

The greater the equality of opportunity in a society becomes, the more obvious becomes the inequality of the talent and character among individuals, and the more bitter and personal it must be to fail, particularly for those who have some talent but not enough to win them second or third place.

(Auden, ‘West’s Disease’)

But surely – surely? – literature is not a competition. Literature is not a sport. One cannot measure oneself by the usual standards of success.

The writer who allows himself to become infected by the competitive spirit proper to the production of material goods so that, instead of trying to write his book, he tries to write one which is better than somebody else’s book is in danger of trying to write the absolute masterpiece which will eliminate all competition once and for all and, since this task is totally unreal, his creative powers cannot relate to it, and the result is sterility.

(Auden, ‘Red Ribbon on a White Horse’)

Let’s not kid ourselves.

It is a competition.

It is a sport.

One does measure oneself by the usual standards of success.

When writing about any great writer – or indeed about anyone who has achieved great things – one can’t help but compare oneself.

*

(Throughout his life, Philip Larkin often measured himself against Auden. Auden, for him, was the Truly Great Man: Philip Larkin loved Auden. When he bought a car in 1984, for example, an Audi, he said he liked the name ‘because it reminds me of Auden’. In a letter to a friend in 1959, extolling the virtues of Auden’s poem ‘Night Mail’, he wrote in horrible realisation, ‘HE’D BE ABOUT SEVEN YEARS YOUNGER THAN ME,’ but then quickly added, ‘I reckon he’d shot his bolt by the age of 33, actually.’ Again, when Larkin was awarded the Queen’s Medal for Poetry in 1965, he told an interviewer, ‘Take this Queen’s Medal. I’m 42, but he got it for “Look, Stranger!” when he was 30. Mind you, I feel he was played out as a poet after 1940.’ This scuttering between despair and disdain is typical of Larkin in general but it is also typical of his attitude towards Auden in particular. He prefaced a home-made booklet of poems in 1941 with the gulping confession ‘I think that almost any single line by Auden would be worth more than the whole lot put together.’ When, in 1972, Auden’s bibliographer Barry Bloomfield asked Larkin if he might be his next subject, Larkin expressed both delight and dismay: Bloomfield ‘has switched to me now Auden’s gone’, he told his friend Anthony Thwaite; ‘I am not much more than a five-finger exercise after Auden,’ he apologised to Bloomfield.)

*

If Philip Larkin was no more than a five-finger exercise compared to Auden, then this – this! – is, what? At the very best, a one-note tribute?

*

Polyphony

↓

Monophony

↓

Penny whistle and kazoo

*

Parnassus after all is not a mountain,

Reserved for A.1. climbers such as you;

It’s got a park, it’s got a public fountain.

The most I ask is leave to share a pew

With Bradford or with Cottam, that will do.

(Auden, ‘Letter to Lord Byron’)

*

Park?

Fountain?

Pissoir.

*

Perhaps one of the only things the rest of us share with the truly great writers is the sense of struggle, the sense of inadequacy.

Flaubert: ‘Sometimes when I find myself empty, when the expression refuses to come, when, after having scrawled long pages, I discover that I have not written one sentence, I fall on my couch and remain stupefied in an internal swamp of ennuis.’

Gerard Manley Hopkins: ‘Birds build – but not I build; no, but strain, / Time’s eunuch, and not breed one work that wakes.’

Katherine Mansfield: ‘For the last two weeks I have written scarcely anything. I have been idle; I have failed.’

We all know that feeling, that sense of despair and woe-is-me and all-I-taste-is-ashes, and all-I-touch-has-turned-to-dust.

Great writers, it seems, are not necessarily those who are most confident about their own capacities or skills. They are more often keenly aware that words are failing them, and that they are failing words. Like us, they find it difficult.

*

Or rather, most of them find it difficult: Auden was convinced of his own skills and capacities from an early age and went on to fulfil and exceed his early promise.

(His tutor at Oxford, Nevill Coghill, recalled Auden announcing his intention to become a poet. Jolly good, said Coghill – or something donnish to that effect – that should help with understanding the old technical side of Eng. Lit., eh, old chap? ‘Oh no, you don’t understand,’ replied Auden – or again, words to that effect – ‘I mean a great poet.’)

He seems never to have been lacking in confidence. He seems always to have been convinced not merely of his brilliance but of his sovereignty.

‘Evidently they are waiting for Someone,’ he told his friend Stephen Spender.

He was that Someone.

*

And me, who am I?

If nothing else, one of the things I have realised over the course of the past twenty-five years, in trying to write a book about W. H. Auden, is the obvious fact that I AM NOT W. H. AUDEN.

*

Other people realise they’re not their heroes much earlier, but I was in the slow learners’ class in school and seem to be a slow learner still.

I think I probably believed that one day – through sheer willpower and determined slog, through dogged persistence and self-discipline – I might somehow overcome my weaknesses and become an artist of some significance.

It is only recently that I have come to accept my true role and status, which is, obviously, naturally, inevitably, as an utterly insignificant bit-part player in the world of literary affairs.

This is the real trouble with studying major writers: it reminds one of one’s minority status.

(Great Lies of Literature No. 1: reading great literature is good for the soul. The truth: reading the greats does not just uplift; it also casts down.)

*

F. R. Leavis once described E. M. Forster, when compared with Henry James, as ‘only too unmistakably minor’ – though Forster accurately remarked of James that though he might have been a ‘perfect novelist’, it wasn’t a ‘very enthralling type of perfection’. It hardly needs stating that I’m not in James’s league, nor in Forster’s – but, alas, the real truth is that I’m not even in Leavis’s league, which is a league no one in their right mind would want to be in anyway, a league whose entry requirements include anger, bitterness and envy. (He was not a great fan of Auden, Leavis, particularly not his irony, which he described as ‘self-defensive, self-indulgent or merely irresponsible’. God, one wonders, what would F. R. Leavis make of this?) Reading Leavis, it is clear that I am only too unmistakably minor even in relation to him writing about Forster writing about James – a gnat on a flea on the shoulders of giants. Forster has an essay, ‘The C Minor of that Life’, whose title is an allusion to Browning’s poem ‘Abt Vogler’, the last line of which begins ‘The C Major of this life’. This life is neither C Major nor Minor, but C very much Diminished.

*

(This book, clearly, is not just about Auden. It’s about everything else I’ve been thinking and reading while I’ve been thinking and reading Auden, and which has influenced my thinking and reading of Auden. As Mr Weller long ago explained to his son, Sam – the archetypal Cockney geezers – in The Pickwick Papers: ‘Ven you’re a married man, Samivel, you’ll understand a good many things as you don’t understand now; but vether it’s worth while goin’ through so much, to learn so little, as the charity-boy said ven he got to the end of the alphabet, is a matter o’ taste. I rayther think it isn’t.’)

*

Other things I have come to realise, in passing, as I have been trying to write a book about W. H. Auden, over the course of the past twenty-five years:

Despite what you may have heard, one’s talents do not necessarily grow and develop over time. One’s character does not necessarily blossom. Things do not necessarily work out. The unique gift that you might have thought you had to offer the world does not necessarily become apparent to you or to anyone else. There is not just the possibility of loss and waste and failure: failure and waste and loss are inevitable. (William Empson, in that wonderful remark about Gray’s ‘Elegy’, in Some Versions of Pastoral – my absolute favourite among all of Empson’s wonderful remarks: ‘And yet what is said is one of the permanent truths; it is only in degree that any improvement of society could prevent wastage of human powers; the waste even in a fortunate life, the isolation even of a life rich in intimacy, cannot but be felt deeply, and is the central feeling of tragedy.’)

There are many individuals whose natural talents far exceed your own.

There are many individuals whose natural talents may seem far less than your own and yet who will inevitably succeed far beyond your own small successes.

There will always be something, someone, some circumstance pushing you to the side of your life, something obscuring the view, something preventing you from doing what you thought you might do or being who you thought you might be. For me, that something, that someone, was Auden: for me, Auden was the problem as well as the solution. Perhaps this is always the case with the people who really matter: wives, husbands, lovers, friends.

*

So what is the final justification for this book, which has taken so long, for so little apparent reason, and which obviously amounts to so little – 70,000 words, give or take, expended in trying to explain Auden’s 99-line poem?

*

I can’t really claim, as is now often claimed by those attempting to write about their relationship to other – often, conveniently, dead – writers, that this is a record of a ‘relationship’. If it is a relationship, it is clearly a very odd sort of relationship, since I never met Auden and realistically never would have met Auden, and if I had done, it seems doubtful we would have got on. He could never have been, for me, as he was for the poet John Hollander, and for many others, ‘Like a clever young uncle’ or ‘like a wise old aunt’: I am not someone blessed with such uncles or such aunts. My actual uncle Dave was a minicab driver; my auntie worked at Yardley’s. There have been, for me, no mentors: there has been no extending of the hand, no leg-up, no hand-me-downs. (In Ulysses, Mr Deasy asks Stephen what an Englishman is proud of – ‘I will tell you, he said solemnly, what is his proudest boast, I paid my way … I paid my way. I never borrowed a shilling in my life. Can you feel that? I owe nothing? Can you?’ It’s true.) But then, in fairness, I was never really protégé material. My relationship with Auden – had there been anything like a relationship – would have been at best a very vague acquaintanceship, a relationship from a great distance, a one-sided sort of relationship, not so much teacher-to-pupil or guru-to-disciple, as master to his valet.

I am beginning to lose patience

With my personal relations:

They are not deep

And they are not cheap.

(Auden, ‘Case Histories’)

This book does not therefore record my ‘relationship’ with Auden – I have no relationship with Auden in any meaningful sense – so much as my relationship with language, or my relationship with language through Auden. Auden as the OED, as Roget’s, as Brewer’s, Fowler’s, Webster’s, the Encyclopaedia Britannica, and Partridge’s Usage and Abusage and Dictionary of Slang and Unconventional English – all of them, combined.

*

(‘Is it one of those How So-and-So Changed My Life type of books?’ asks a friend. ‘No,’ I say. ‘That’s a shame,’ they say. ‘People really like those sorts of books.’ ‘It’s more about my relationship with language, and literature, and ideas,’ I say. ‘Hmm,’ says my friend. ‘Well, good luck with that.’)

*

One of Auden’s great ambitions was to be included in the OED – ‘that inestimable successor to Holy Writ’, as the critic I. A. Richards called it – with his words and phrases listed as coinages and exemplars. It was an ambition he fulfilled many times over, being credited with more than 100 significant usages, including the phrase ‘Age of Anxiety’ (defined, in the second edition of the OED, as ‘the title of W. H. Auden’s poem applied as a catch-phrase to any period characterized by anxiety or danger’), the adjective ‘entropic’, and the noun ‘agent’ (abbreviated from ‘secret agent’). According to the biographer Humphrey Carpenter, describing Auden’s study in his house in Kirchstetten, ‘The most prominent object in the workroom was a set of the Oxford English Dictionary, missing one volume, which was downstairs, Auden invariably using it as a cushion to sit on when at table – as if (a friend observed) he was a child not quite big enough for the nursery furniture.’

*

(The missing volume – Auden’s hardback dictionary cushion – was, according to Carpenter, volume X of the OED: (Sole–Sz). Which might provide a nice alternative title for this book, would it not? Sole–Sz, a title which offers an obvious homophonic pun on ‘sole’ and which also usefully alludes to Roland Barthes’ S/Z, that impossibly complicated book about Balzac’s story ‘Sarrasine’, which was once required reading on every grad course in literary theory, with its typologies of interacting SEM codes and SYM codes, and REF, and ACT and HER codes, and which therefore might suggest that this book too is a work of great theoretical sophistication. Maybe not.)

*

So, not a book about my relationship with Auden. A book about my relationship with language.

*

But we all know – we don’t have to be a Roland Barthes to know – that there can be no simple explanation in language of our relationship with language. It’s like using a mirror to look at a mirror. Words are insufficient to do justice to words, let alone to everything else.

So the enterprise is doomed again.

*

This is all entirely obvious, I suppose, to most people. And barely needs stating.

All I can safely say, then, is that it has taken me twenty-five years to work out the entirely obvious.

And these are my notes.

In literature, as in life, affectation, passionately adopted and loyally persevered in, is one of the chief forms of self-discipline by which mankind has raised itself by its own bootstraps.

(Auden, ‘Writing’)

Just a Title

The reason (artistic) I left England […] was precisely to stop me writing poems like ‘September 1, 1939’, the most dishonest poem I have ever written.

(Auden, letter to Naomi Mitchison, 1 April 1967)

‘September 1, 1939’.

If you know anything about the poem – and you may well know more about it than I do, in which case I should warn you, this is probably not the book for you, it’s a book for my friends and my cousins, for everyone who has ever said to me, ‘W. H. Who? September the What?’ – you will know that it was a poem that over the course of his lifetime Auden variously revised and then disowned. It is a poem with a long and troubled history. It is a poem that has undergone a lot of changes. Perhaps that’s part of its appeal: it is a poem with another life, an afterlife. It is a poem, like a person, that comes with a lot of baggage.

Even the title changed. We may know it as ‘September 1, 1939’, but on first publication, in the American magazine the New Republic, on 18 October 1939, it was ‘September – 1939’; in Auden’s collection Another Time (1940) it then became simply number four in a sequence of ‘Occasional Poems’, thus, ‘IV. September 1, 1939’; and not until subsequent versions and revisions did it appear as both ‘1st September 1939’ and ‘September 1, 1939’.

Auden had a strong habit of revision. (He had strong habits generally: drug habits, writing habits.) He liked to change the titles of his poems, just as he liked to change all other aspects of his poems: ‘Palais des Beaux Arts’ became ‘Musée des Beaux Arts’; ‘The Territory of the Heart’ became ‘Please Make Yourself at Home’ became ‘Like a Vocation’; ‘The Leaves of Life’ became ‘The Riddle’; et cetera, et cetera; the list is very long.

Not everyone approved of all these rethinks and rewrites, of course. A lot of people thought them arrogant, or foolish, or merely eccentric. The poet and critic Randall Jarrell thought Auden’s revisions were not only arrogant, foolish and eccentric; he thought they were morally reprehensible: ‘Auden is attempting to get rid of a sloughed-off self by hacking it up and dropping the pieces into a bathtub full of lye,’ he wrote, figuring Auden both as a snake, and as an acid-bath murderer.

(If not the greatest critic of poetry in the twentieth century, Randall Jarrell was certainly the greatest reviewer of poetry in the twentieth century, and to be a great reviewer of anything you need to be given to peculiarly vivid language: Clive James writing on television was given to peculiarly vivid language; Anthony Lane writing on films in the New Yorker; Dorothy Parker; Virginia Woolf, oddly. But Jarrell was undoubtedly the greatest, the most vivid of all, and he had what one might generously describe as a love–hate relationship with Auden. According to fellow poet John Berryman, Jarrell knew Auden’s mind ‘better than anyone ought to be allowed to understand anyone else’s’, even when Auden was in two minds.)

*

But those tiny little adjustments to the title of this poem, do they really matter?

*

Yes.

No.

Of course.

Not really.

Same as anything else.

Does it matter if you leave out that little pinch of salt in your recipe? Would it matter if I was called Samson, instead of Sansom, or Sampson? Simpson? Ivan, not Ian? Ivor? Ifor? Oscar?

(Some years ago, invited to give a reading at a library, I was introduced as C. J. Sansom – the bestselling author of historical crime fiction, and no relation. When I explained that I was not, alas, C. J. Sansom, two women in the audience got up and left. Which was fine, really. The other half of the audience remained.)

I mentioned that I was afraid I put into my journal too many little incidents. JOHNSON: ‘There is nothing, Sir, too little for so little a creature as man. It is by studying little things that we attain the great art of having as little misery and as much happiness as possible.’

(Boswell, The Life of Samuel Johnson, LL.D., 1791)

If one were a certain kind of critic I suppose one might note that a poem titled ‘September 1, 1939’ clearly, deliberately recalls Yeats’s poem ‘September 1913’, signalling that this is a poem written in response to another. (In his poem ‘In Memory of W. B. Yeats’, Auden calls Yeats ‘silly like us’, which he certainly was: silly like us for believing that we might be able to simplify and sum things up.)

One would also note that a poem titled ‘September 1, 1939’ clearly announces itself as an American poem: Americans write Month/Day/Year; in the UK we normally write Day/Month/Year.

One might note further that to use a date as a title perhaps suggests that the poem might be something like a diary entry, setting certain expectations and a tone. It suggests that the poem might have been composed or conceived on that specific date, for example – such as Wordsworth’s famous sonnet ‘Composed upon Westminster Bridge, September 3, 1802’ (which was in fact originally published as ‘Composed upon Westminster Bridge, September 3, 1803’, which rather suggests that it might be foolish simply to read dates in poems as facts in a poet’s life, not least because the actual date of Wordsworth’s crossing Westminster Bridge, according to his sister Dorothy’s journal entry, was 31 July 1802).

(One might speculate further, parenthetically, that a minor artist is someone who is very precisely not prepared to risk breaking and bending the rules a little. A definition of the minor artist – the non-Wordsworth, the un-Auden – is that they are not prepared to fiddle around with inconvenient details like dates and facts and figures. As everyone knows, Tennyson got it wrong in ‘The Charge of the Light Brigade’ when he wrote, ‘Into the jaws of Death, / Into the mouth of Hell / Rode the six hundred’ – it was closer to 700 who rode into the jaws of death. But when challenged on the point, Tennyson is said to have remarked, ‘Six is much better than seven hundred metrically, so keep it.’ Poets are not historians, or statisticians.)

One might suggest, furthermore, that a poem whose title appears to commemorate some famous historic event is not necessarily a poem written with the sole intent of commemorating that event. Even Yeats, that great commemorator, who loved to use dates for titles – ‘September 1913’, written after the Dublin lock-out, and ‘Easter, 1916’ – wasn’t writing manifestos or reports. The titles may be significant but they are hardly a full explanation. Yeats’s poem ‘Nineteen Hundred and Nineteen’, for example, was originally titled ‘Thoughts Upon the Present State of the World’, which suggests exactly the kind of meandering activity that is going on in much of his work, which is then given shape and focus by the addition of a date and title, rather than proceeding in a straight line either from or towards it.

Which might lead one, finally, towards the conclusion that though a title may appear to come first, very often it may in fact come last: a poem’s title may be a post hoc rationalisation. It might also be a false sign.

Or, ultimately, just a title.

*

Anyway.

I’m not that kind of critic.

*

September 1, 1939, as it happens, was a Friday.

Auden had just returned to New York from his road-trip honeymoon with his young lover Chester Kallman. For almost three months – ‘the eleven happiest weeks of my life’ – they had criss-crossed the nation, from New York to Washington, New Orleans, New Mexico, Arizona and Nevada and on to California. ‘C is getting quite a tan’, Auden told Chester’s father, ‘and I scribble away.’

But now the summer of love was over. ‘At 32½ I suppose I shall not change physically very much for some time except in weight which is now 154lbs […] I am happy, but in debt […] I have no job. My visa is out of order. There may be a war. But I have an epithalamion to write and cannot worry much.’

(There may be a war. But I have an epithalamion to write and cannot worry much. It’s reassuring, isn’t it, that like us – whatever else was happening – Auden had stuff on. I remember when the Berlin Wall came down, and it was the end of the Cold War and the beginning of a New World Order, and I was in my early twenties and I was working as a farm labourer up in the Craigantlet Hills, just outside Belfast, and I’d listen to the news on the radio in the morning, but it was like listening to news from another planet: I was busy; I had work to do; I had stuff on. It’s the whole point of Auden’s poem ‘Musée des Beaux Arts’, which is about Brueghel’s painting The Fall of Icarus: ‘About suffering they were never wrong, / The Old Masters: how well they understood / Its human position; how it takes place / While someone else is eating or opening a window or just walking dully along.’ It turns out that I have spent a lifetime walking dully along, unable and unwilling to recognise the extraordinary and the other while it’s happening all around me. Like Auden’s description of the dogs in his poem, I have simply ambled on, leading my doggy life. Attending to Auden is probably the closest I’ve ever come to stopping and noticing something truly amazing, an actual Icarus, a boy falling out of the sky.)