Полная версия

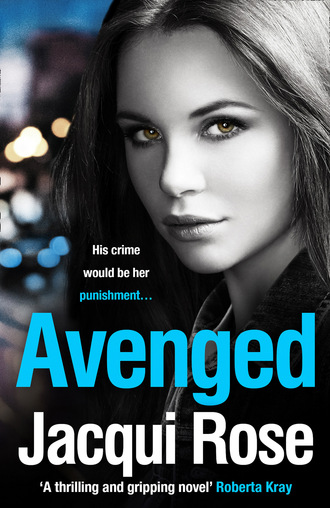

Avenged

Frantically, he picked up his speed; his heart racing faster and faster as the rain, pocketed by the Kerry wind, swirled in the air, battering his face.

Patrick knew he couldn’t outrun the car and get to the side lane in time; petrified, he threw himself into the hedgerows, feeling the gorse cutting at his skin.

The car hurtled past; O’Sheyenne hadn’t seen him as he raced along the road, sending up a spray of water. After waiting another five minutes, Patrick began to run. He was nearly at the church now and it was almost as if what he’d seen back there in the Brogans’ house hadn’t been real.

Desperately trying to distract himself from the images of the Brogans in his head, Patrick thought about his dad, Tommy Doyle; the man he’d once looked up to. The man he’d once been able to trust. But since his mother’s death from an accident ten years ago, his father had drowned himself in whiskey and self-neglect.

His father was a hulk of man who had at one time been hailed a hero as one of Ireland’s finest champion boxers, but now his days were spent drinking, and his nights bare-knuckle fighting to earn the money which barely put food on the table but always put the drink in his belly.

Even though Patrick had only been six when his mother had died, he missed her so much. Even now he didn’t truly know how she’d died. He’d been told she’d fallen down the stairs and broken her neck, but there were various stories and rumours around the village as to how it’d really happened. He’d heard she’d been drunk. He’d heard she’d been sleep-walking. But, worst of all, he’d heard his father had had something to do with it.

With the church coming into view, Patrick shook himself from his thoughts, falling into the heavy wooden doors and flinging them open to be greeted by a sea of heads turning towards him.

‘Patrick Doyle, what’s the meaning of this? Do you not know what it is to be in the house of God? If you’re not here to attend choir practice then kindly leave.’

Patrick, giving a weak smile to Mary, stood trembling, suddenly painfully aware of his own appearance. His black hair hung soaked and matted over his forehead. His sodden second-hand clothes clung to his body and bubbles of rain water squirted out in tiny streams from the hole in his shoes. He was desperate to tell Father Ryan what had happened after the priest had driven off. He needed to tell him about the Brogans, but he was unable to find the words.

‘Well? Are you staying or leaving?’ The harsh tone of Father Ryan’s voice echoed round the church.

With Patrick not forthcoming, Father Ryan grabbed him by his arm, pulling him to the back of the church.

‘I’m speaking to you, Doyle. What have you to say for yourself? What’s going on?’

Patrick stammered, ‘I … I … er …’

Father Ryan slammed down the prayer book on the back of the wooden pew, making the young children in the choir pews jump with fright. ‘Speak up, boy; I haven’t got time for this.’

Patrick paled. ‘It’s O’Sheyenne.’

Hearing the name, Father Ryan shoved Patrick even further away from everybody’s hearing. He lowered his voice to a whisper. ‘What’s happened?’

‘After you left, Mr O’Sheyenne … Mr …’

Much to the frustration of Father Ryan, Patrick stopped, fear preventing him from saying anything else.

‘For God’s sake, boy, tell me.’ Matthew Ryan paused, then caught sight of something on Patrick’s coat. With trepidation, the priest spoke. ‘What’s that?’

Patrick looked down in horror at the bloodstain on his coat. It must have come from Connor when he was next to him in the car. But before he was able to answer the priest, the doors of the church were thrown open.

Standing, swaying in shock, was one of the villagers.

‘Quick! I’ve just passed the Brogans’ house. Their door was open … I think they’re both dead.’

As the cutting Irish wind whipped round his face, it seemed to Patrick Doyle that the whole of the village, led by a tight-faced Father Ryan, had decided to find out what was going on; an unholy candlelight procession of curious onlookers followed him down the road towards the Brogans’ tiny cottage.

The lane down to the cottage was slippery and Patrick could feel his feet moving faster and faster as he hurtled along the road. Images of the Brogans and O’Sheyenne flashed in his head, combining together in a confusing mix of panic.

He ran whilst the rain continued to splinter down, causing him to lose his balance. He scrambled up, feeling, yet not reacting to, the sting of his hands as they grazed and bled from the hard stony ground. He was first to arrive at the Brogans’ house; even though he’d seen the horror of it all only an hour or so before, looking at the bloody scene again made Patrick freeze at the door then turn to be sick.

He could see Connor’s blood splattered all over the walls, the lifeless bodies of the couple in the middle of the room and, in the corner, the empty cot.

‘Saints and the holy mother preserve us! Who could have done such a thing?’ A villager spoke as he stood shoulder to shoulder with Patrick at the door. A throng of people came up behind, pushing eagerly forward in an attempt to get a look at the horror which lay within.

‘Did anyone see anything?’

The room fell silent as dozens of onlookers, squeezing themselves into the kitchen, formed a circle around the room, staring at the slaughtered couple.

‘I saw someone earlier coming out of here.’ A man Patrick recognised from the local bakery spoke up.

‘Who? Who?’ The cry sounded around the room.

‘I couldn’t make out his face. I was a distance away and it was dark, but the person I saw coming out of here was tall … strong looking, to be sure.’

The villagers looked puzzled, reflecting on the baker’s words, before another voice shouted out from the back.

‘That sounds like Tommy Doyle!’

In a cacophony of gasps, prayers and cries, the villagers began to shout out. ‘He’s capable of something like this’, ‘I always knew he was trouble’, ‘The man’s a monster’, ‘It must be him.’

Alarmed, Patrick turned to face the crowd. ‘No, it wasn’t my da!’

‘Then he’ll be able to tell the Gardaí that … Call them! Call the Gardaí! Tommy Doyle should pay for this.’ The shout was bellowed out by a man from the back of the room. As the crowd joined in again, shouting their agreement, Patrick’s blood ran cold.

‘No! Please! Wait! Me da didn’t do it. I swear it wasn’t him.’

The man from the back continued to talk. ‘We all know what he’s like when he has a drink inside him. Raging for a fight. ’Tis still a mystery what happened to your mother.’

Patrick’s face reddened. His anger and hurt shone through. ‘Leave my ma out of it; this has nothing to do with my da, I tell ye!’

Someone else called out. ‘’Tis no mystery; we all know what really happened to poor Evelyn.’

Patrick cried, ‘Stop! … Stop! You don’t understand. He didn’t do it.’

The first man shouted out again, ‘Where is he anyway? We need to find him. Everyone, go! Do not stop until you find Thomas Doyle.’

Patrick swirled around to look at Father Ryan. ‘No, wait. Father, tell them. Tell them me da couldn’t have done this … he couldn’t have, because … because … I know who did!’

‘Really? We’d all like to hear this. Tell us, Patrick; we’re fascinated.’

Slowly, Patrick turned round to look at the person who’d just spoken, watching as the crowd parted. There, in front of him, was Donal O’Sheyenne.

Patrick spoke, quietly at first, then he became gradually louder. ‘It was him … It was him! Father, it was him!’ Patrick pointed furiously at Donal.

Father Ryan opened his mouth to speak but it was Donal who got there first. He stared at Patrick, dancing amusement in his eyes. ‘Are you sure about that? From what I just heard it was your da.’

‘He never had anything to do with it. You know that.’

Donal gave Patrick a wry smile, menacing in the candlelight. ‘There’s no point trying to defend him, Patrick. The sins of your da’s actions are probably dripping from his hands as we speak, wouldn’t you say so, Father Ryan?’

Father Ryan gave Donal a hostile stare but turned away quickly as Patrick began to address him.

‘Father Ryan, you’ve got to believe me.’

Matthew Ryan shifted uncomfortably. ‘Enough, boy! Let me think.’

Patrick was distraught. ‘It’s true! You’ve got to believe me.’ He looked round at the sea of people; his eyes pleading with them as he saw the condemnation on their faces.

‘I saw Mr O’Sheyenne earlier. I swear. He had Connor in the car. He’d beaten him up then and afterwards he came back here to finish the job.’

Donal smirked. ‘I’ve no idea what you’re talking about.’

‘It’s true!’

O’Sheyenne shook his head. ‘Then why didn’t you say anything then, hey boy? Why would you not say anything to anyone when you saw me with this poor wretch in the back of my car? Why didn’t you tell Father Ryan earlier or even call the Gardaí?’

To no-one in particular, Patrick cried, ‘I tried. I did. I was going to, but I couldn’t because …’

Donal interrupted. ‘Because it’s not true. This is a mighty big accusation, Patrick, and seeing I was with Father Ryan most of the night, it’s also an untrue one. Not even a good man like meself can be in two places at once.’

Patrick shouted. ‘You’re lying! You’re lying.’

‘Shall we put it to the test, Paddy?’ Donal turned to speak to Father Ryan. ‘I was with you all night. Isn’t that right, Father?’

Stammering slightly, Father Ryan fidgeted with the hooks on his cassock as he felt the gathered crowds stare.

‘Yes … yes. That’s right. Er … Mr O’Sheyenne had come to see me earlier and was waiting for me to finish choir practice. He was sitting at the back of the church the whole time.’

Patrick shook his head furiously. ‘No! No! That’s impossible; you know it is!’

‘Stop, boy!’ Father Ryan snapped at Patrick. ‘I don’t want to hear any more.’

Red-faced and holding back the tears, Patrick gawked at the priest. His voice rasping. ‘Please, please, you know I’m telling the truth—’

‘Don’t make this harder for yourself. Get yourself home now.’ Father Ryan stared into Patrick’s face. The man was inches away, allowing him to see the crease of tiredness around the priest’s mouth and eyes.

Through a haze of tears, Patrick stumbled out of the cottage; desperate to find his father to try to warn him.

He couldn’t make sense of what was happening, but most of all, he couldn’t understand why Father Ryan had lied.

Once Patrick and the other villagers had left the Brogans’, Father Ryan grabbed hold of Donal’s arm, who looked down at the grip with amusement.

‘Can I help you, Father?’

Father Ryan hissed through his teeth. ‘Look at the carnage you’ve caused. Hold your head down in shame.’

‘My head, Matthew? I’d say you’d need to hold yours.’

The priest’s face was a picture of rage. ‘It’s not me that has blood on my hands.’

‘I’d say that was a matter of opinion, wouldn’t you?’

Father Ryan pointed at the slaughtered couple. ‘This. This has nothing to do with me.’

Donal tapped Father Ryan on his back and grinned; bursting out into laughter. ‘Why, Father, you crack me up, so you do. It must be wonderful to purge yourself of your sins.’

‘A massacre wasn’t what we agreed.’

‘I don’t think you’re in a position to agree anything.’

Father Ryan’s face flushed. ‘I have no option but to go to the Gardaí, O’Sheyenne.’

Donal grabbed Father Ryan round his throat, squeezing it hard. Barely able to breathe, the priest wheezed, ‘I can’t be part of this.’

‘I’d say you already are. All I need you to do is go along with it being Tommy Doyle until I tell you otherwise and figure something else out. Do I make myself clear?’

Father Ryan gave a tiny terrified nod. Satisfied he’d made his point, O’Sheyenne let go of the priest’s neck, watching whilst he gasped and struggled for breath.

‘Now I’ll bid you goodnight, Father, and I’ll leave you with a little word of advice: if you’re ever thinking of going to the Gardaí again, take another look at the poor Brogans. We certainly wouldn’t want such a godly man as yourself ending up like that now, would we?’

4

Mary O’Flanagan sat on her bed in the darkness and shivered. She was soaking wet and there was no way she was going to be able to get herself warm. There’d been a power cut. Nothing unusual there; it was a regular occurrence in the village, but tonight the difference was that she was alone.

There was no way she’d be able to start the parlour fire without her da. Besides, the logs in the yard were probably soaking wet, which meant she’d have to get the wood from the shed in the back field on her own; and one thing Mary O’Flanagan hated was the dark.

Her parents had gone out; taking it upon themselves to join the search party for Patrick’s father. She wasn’t quite sure what good they’d do. Her own father was a tiny, timid man and if he were to come across the formidable Tommy Doyle hiding out, she was certain he’d bag himself. Not unkindly, Mary laughed out loud at the image in her head.

Thinking about Tommy Doyle made Mary wonder about Patrick. She hoped he was all right. She hadn’t been able to talk to him but he’d looked as handsome as he ever did when he’d stood soaking wet in the church that evening.

She and Patrick had been friends as far back as she could remember; much to her parents’ dismay. And a few months ago he’d made her swear she’d marry him once he’d made his fortune.

‘Patrick Doyle, I’m a good Catholic girl and good Catholic girls don’t swear. Perhaps if you came to church more often you’d know that.’

‘Don’t be acting the maggot with me, Mary O’Flanagan. The Dublin chancers would blush to hear the mouth on ye.’

She’d pushed him gently. ‘Feck off, Paddy!’

‘Ah, you see. How can I make ye me wife, Mary, if you’ve a tongue which would eat the head off a viper?’

‘I never said I’d be your wife, Patrick Doyle, and you’re no more likely to make your fortune than poor Bridget Henley with those rotten apples she sells.’

‘Well, that’s a fine thing to say to a man, Mary O’Flanagan!’

She’d scoffed, but the kindness had shone through her eyes. ‘A man, Paddy? You’re nothing more than a boy.’

‘I’m sixteen, Mary, and I can hold me own.’

She’d fallen silent before saying, ‘And if I were to marry you, Patrick. What would we name our first child?’

Patrick had pondered on the question. ‘I take it, it’ll be a boy.’

Indignantly, she’d replied. ‘It’ll be no such thing. It’ll be a girl and I shall call her Franny.’

Patrick had burst out laughing. ‘Franny? And what sort of name is that?’

‘Francesca. Franny for short. And for your information, it’s a good Catholic name, Patrick Doyle – but that’s something you’ll know nothing about either.’

‘Well, I won’t allow it! Franny. Have you ever heard the like?’

She’d pulled a face but she’d had a twinkle in her eye. ‘And have you ever heard what a pig you are, Patrick Doyle? And, to be sure, I certainly won’t be marrying you now.’

‘Then I’ll just have to marry old Bridget Henley.’

‘You’ll do no such thing … and to think I had a present for ye. I shan’t give it ye now.’

Patrick’s face had lit up. ‘For me? You remembered me birthday?’

She’d spoken haughtily. ‘I did indeed. Not that you deserve anything, not now you’re going to marry Bridget Henley.’

‘Oh Mary, you know you’re the only girl for me. And I reckon if I kissed poor Bridget her false teeth might fall out.’

She’d grinned at the thought and then taken a tiny box out of her coat pocket and handed it to Patrick.

He’d opened the box with delight on his face. In it was a silver chain with a tiny cross on it.

‘Do you like it?’ she’d asked eagerly. ‘I saved up all year.’

His eyes had glistened with tears. ‘I love it, Mary. Like I love you. I should give you something.’ Patrick had looked around, then seeing an early bloom of gorse, the bright yellow pea-flower which in the spring months seemed to light up the landscape of Kerry, ran to pick some.

She’d shouted. ‘Patrick, you’ll tear your hands on the prickles—’

‘Then tear them I will. I have to give my girl a blossom.’

After five minutes of Mary giggling and Patrick struggling with the stems of sharp tiny spikes, he’d conceded defeat and returned with just a dozen yellow gorse petals.

‘When we’re married, Mary, I’ll fill our house with flowers, but for now here’s a petal for every month of the year. Every month that I love you.’

She’d taken the petals and smiled sweetly. ‘Well, to be sure, it’s true to say in me life I’ve never wanted a whole bunch of flowers. Why would I want that when the real beauty is in the petals?’

Patrick had winked at her, grateful for her kind nature.

‘You know what they say around here, Mary? When gorse is out of blossom, kissing’s out of fashion; so it looks like we’re in luck.’

They’d laughed as they always did, pushing and shoving each other in jest, then Patrick had caught hold of her and leant in for a kiss.

Sitting on the bed, Mary jolted herself out of her memories; not wanting them to go any further because she certainly didn’t want to have to confess them to Father Ryan on Sunday.

On the day Patrick had kissed her, she’d cycled all the way to the church at Kenmere – almost twenty miles away – to make her confession. Even though the hard seat on her bike had rubbed and caused painful blisters on her inner thighs, it’d still been better than having to confess to Father Ryan.

She certainly wasn’t keen on making the long trip again and she certainly wasn’t going to make a confession here, at St Peter’s, so the easiest thing was to have no more thoughts of Patrick, especially in the direction they were beginning to head.

About to take a deep sigh, Mary suddenly held her breath. She heard the creak of the wooden stairs. There it was again. It wasn’t her parents; they always yelled a cheery hello as they entered through the side door. The creak sounded again, only this time louder.

Mary’s mouth began to dry as her heart pounded. Almost immediately her eyes filled with tears as her whole body began to shake, terror gripping her.

As the howl of the wind swirled through the trees, and the rain struck against the arched window, Mary heard footsteps coming along the landing. Petrified, she opened her mouth to cry out. Then she heard her name.

‘Mary? Mary?’

Cautiously, Mary got up; tentatively crossing to the other side of the room.

‘Mary?’ The voice, just outside, was gentle and hushed.

‘Patrick? Patrick? Is that you?’ She reached for her bedroom door, opening it quickly, but she suddenly let out a scream. A large hand pressed against her face and a small beam of torchlight hit her eyes.

‘Mary, for the love of God, I’m not going to hurt you. I promise. Just don’t scream.’

The hand was lowered from her mouth and Mary stood staring into the face of Tommy Doyle. She stepped backwards, reaching out for the wall behind her.

‘What … what are you doing here?’ Mary tried not to show her fear but she could hear it in her voice. ‘You do know the Gardaí are out looking for ye?’

‘Ah Jaysus, Mary. Don’t look so frightened. I never meant to give you a fright. Patrick would have me guts if he thought I’d scared ye.’

Seeing her fear, Tommy spoke again. ‘I never did it love. I swear.’

‘Then why don’t you tell them that?’

Tommy shook his head. ‘When I heard they were looking for me, I knew I’d never stand a chance. Who’s going to believe me? I know what they all think of the likes of me.’ There was a long pause as Tommy stared pleadingly at Mary. Tears brimmed in his eyes. His voice was soft as he spoke. ‘Connor was my friend; there’s no way I would hurt him, or Clancy for that matter. For all her nagging ways she was a good woman.’

Even though Mary could smell the alcohol on Tommy as he spoke, she began to feel more at ease. She smiled. ‘I know, Mr Doyle. She was a lovely woman; fierce kind to me.’

‘Call me Tommy.’

Mary bristled, yet again feeling uncomfortable. It didn’t feel right to call an adult by his first name. Then, as if he could read her mind, he spoke.

‘To be sure, if you prefer to call me Mr Doyle, I’m grand with that as well.’

In the distance, above the sound of the storm, voices and barking dogs were heard. Tommy turned in panic to Mary. His face was strained, his voice full of urgency.

‘You’ve got to help me.’

Mary turned her head towards the sound of the voices. They were coming closer and they were sure to be here in a few minutes. ‘I can’t … I …’

‘Please, Mary, I can’t think of anyone else. They won’t be suspicious of you.’

‘What about Patrick? He’d help you. I know he would.’

‘I can’t risk going back home; they’ll be bound to be waiting there and I’m not going to jail for something I didn’t do.’ Tommy’s eyes were wild with fear. ‘Please, you’ve got to help me!’

Just then, a voice came from downstairs. ‘Mary! We’re back. If I didn’t know better, I’d say this storm was the wrath of God. I’ve been a God-fearing man all me life and I’ve never …’

The voice became inaudible as a crack of thunder broke above the small house. Mary looked at Tommy.

‘That’s me da, Mr Doyle. Even if I wanted to help ye; it’s too late now. I’m sorry.’

‘Mary! Didn’t you hear me calling you from downstairs?’

‘No, Da.’

‘Well I was. We’ve come to check on you, to make sure you’re all right. You can’t be too careful with a man like that on the loose.’

Mary stood at the top of the stairs as she watched her da walking up the wooden stairs, followed by other villagers. Then, a moment later, trailing behind dressed in black, Mary saw the ominous figure of Father Ryan.

Father Ryan, her da, her mother, the Brogans, Tommy and his late wife, Evelyn … even Donal O’Sheyenne, who her father was too frightened to have anything to do with. All of them went right back to childhood. All school mates, playground pals; every single one of them.

They’d shared their childhood, their youth and eventually their adulthood together, yet the power and disdain Father Ryan held over his contemporaries, in particular her da, made her seethe with anger. Though it didn’t do her any good: each week it was inevitable she’d feel obliged to confess these dark thoughts she had about Father Ryan to Father Ryan, who she was certain smirked with pleasure as he handed her more Hail Marys than she’d known him give anyone else.

Addressing what her dad had just said, Mary spoke quietly. ‘You don’t know if it’s him, Da. Mr Doyle has always seemed a nice man.’

Mary’s father was standing opposite her, dripping pools of rain water on the highly polished mahogany floor. He smiled at his daughter.

‘Ah, you’re a good girl, Mary, blessed with innocence so you are; seeing no wrong in people. I know you’re sweet on his boy, Mary, but Thomas Doyle is not a nice man. Even when we were children he was no different, always getting into scrapes. Isn’t that right, Father Ryan?’

Father Ryan scowled, irritated at the chatter. ‘Now is not the time to talk the hind legs off a donkey, Fergus O’Flanagan. Plus I think it’s time we had a talk about allowing Mary to be sweet on the Doyle boy.’

Fergus hung his head. ‘Yes, Father. Sorry, Father.’

‘Aye, well that’s as may be, but sorry without action won’t see you through the gates of heaven, Fergus, nor keep Mary on a virtuous road. Come and see me tomorrow and we can discuss it.’

Mary glared at Father Ryan, not just because of his unwelcome interference in her life but because of the way he spoke to her da. She’d always hated it and he’d always done it – belittling him in front of everyone. It angered Mary all the more knowing that they’d gone to school together.