Полная версия

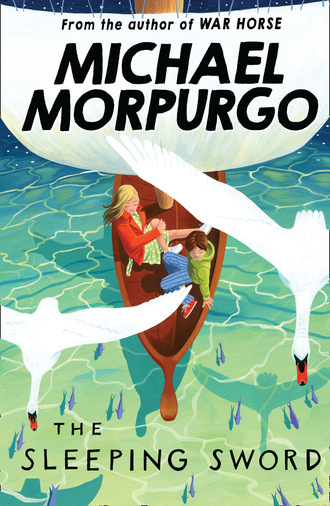

The Sleeping Sword

Also by Michael Morpurgo

Arthur: High King of Britain

Escape from Shangri-La

Friend or Foe

From Hereabout Hill

The Ghost of Grania O’Malley

Kensuke’s Kingdom

King of the Cloud Forests

Little Foxes

Long Way Home

Mr Nobody’s Eyes

My Friend Walter

The Nine Lives of Montezuma

The Sandman and the Turtles

Twist of Gold

Waiting for Anya

War Horse

The White Horse of Zennor

The War of Jenkins’ Ear

Why the Whales Came

For younger readers

Animal Tales

Conker

Mairi’s Mermaid

The Marble Crusher

On Angel Wings

The Best Christmas Present in the World

CONTENTS

Before I wrote my story

The Sleeping Sword by Bun Bendle

1 The dive of my life

2 ‘Not a mummy mummy’

3 Inside my black hole

4 Only one way out

5 Hell Bay

6 One of us

7 ‘Be Happy. Don’t worry.’

8 ‘Be an angel, Bun’

9 Dry bones

10 ‘Isn’t that magical?’

11 ‘No such thing as luck’

12 In my dreams

13 The quest begins

14 Ghost ship

15 Metamorphosis

16 Arthur, High King of Britain

17 The sleeping sword

18 End of the quest

19 ‘Is it really true?’

After I wrote my story

BEFORE I WROTE MY STORY

Before it happened, before the world went black about me, I used to read a lot. I’ve tried Braille, and I am getting better at it all the time, but reading is so slow that way. So now I listen to my audio tapes instead. I’ve got dozens of them on my shelf. The trouble is I can’t tell which is which, so I’ve put my three favourite ones side by side on my bedside table. That way I can find them more easily.

Left to right, it’s The Sword in the Stone, Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, and Arthur, High King of Britain. I’ve listened to those three so often I can say bits of them by heart. But it’s Arthur, High King of Britain I’ve listened to most often, not because it’s the best – The Sword in the Stone is probably the best – but because Arthur, High King of Britain begins and ends on Bryher, on the Scilly Isles, where I live. I can picture all the places so well inside my head and that helps me to feel part of the story, free to roam inside it somehow, to be whoever I want to be, do whatever I want to do.

And that’s my trouble at the moment. There’s so much I can’t do now that I used to do without even thinking about it – you know, ordinary things like going down to the shop, hurdling over mooring ropes, playing football on the green, watching telly, seeing my friends whenever I felt like it, messing about in boats, diving off the quay with them in the summertime. I can still go swimming, but someone always has to be with me. That’s the worst of it, really. I can never go free like I used to.

It’s not so bad at home. I’ve got a sort of memory-and-touch map of the house inside my head, every room, every doorway, every chair. And, provided my father doesn’t leave his slippers in the middle of the kitchen floor – which he often does – and provided no one shifts the furniture or moves my toothbrush, I can manage just about all right. I really hate it if I trip or fumble about or fall over. No one laughs, of course they don’t. In a kind of way I wish they would. Instead they go all silent and feel sorry for me, and that just makes me angry again inside.

And there’s so much I miss – all the colours of the sky and the sea, the blue and the green and the grey, the black and white of the oystercatchers. I can’t picture colours in my head any more, and I can’t picture people’s faces either, not like I could. So, like the oystercatchers, everyone’s a voice now, just a voice. I’m getting used to it, or that’s what I keep telling myself, anyway. I should be after two years. But it still makes me angry when I think about it, the bad luck of it, I mean. I try not to think about it, but that’s a lot easier said than done.

That’s what’s so good about ‘reading’ stories, and ‘writing’ them, too. I’ve made up lots and lots of short stories. I love doing it because I can be whoever I like inside my stories. I can make my dreams really happen. I’m the maker of new worlds. Inside my dreams, inside my stories I can run free again. I can see again. I can be me again.

I don’t actually write my stories, not like other people do. I find the Braille machine slows me down, like it does with my reading. Instead, I tell them out loud into a recorder. That’s how I’m doing this now, and it’s brilliant, because it lets the story flow. I get things wrong of course, and often too, but I just record over my mistakes and on I go. Easy.

A few days ago, I finished my very first long story and this is it. It took me the whole of the summer to write it. It’s dedicated to Anna – you’ll see why soon enough – and I’ve called it . . .

THE SLEEPING SWORD

BY BUN BENDLE

For Anna

CHAPTER 1

THE DIVE OF MY LIFE

IT WAS NO ONE’S FAULT EXCEPT MINE. I WAS showing off. True, I didn’t exactly want to go in the first place, but then I shouldn’t have allowed Liam and Dan to persuade me. On the way back on the school boat from Tresco it had been cold and blustery. All I wanted to do was to get back home and finish reading my book about King Arthur.

Mum was out somewhere on the farm when I got in. We grow organic vegetables (onions, courgettes, tomatoes, lettuces – all sorts) to sell to the visitors – we get a lot of tourists on Bryher, especially in the summer. As usual, she had left my tea on the table. Dad was out checking his lobster pots. I was deep in my book, munching away at my peanut butter sandwich, when Liam and Dan banged on the window. They were in their wetsuits and breathless with running.

‘Bun, we’re going down the quay,’ Liam shouted. ‘You coming?’ It wasn’t really a question at all.

‘I’m reading,’ I replied, ‘and, anyway, it’s cold.’ Liam ignored me.

‘See you down there,’ he said, and they were gone.

On Bryher we were the only boys of about the same age (there’s only eighty people living here on the island anyway; one shop, one church, no school). We grew up together, went over to Tresco school every day together, we went fishing together, did just about everything together. ‘The Three Musketeers’ they call us. If we had a leader it was Liam, most of the time, anyway. He was the smallest of the three of us, and was by far and away the cleverest, too. He had a real gift of the gab, and was a fantastic mimic, as well. Anyone from Mrs Gee (‘BF’ Gee we called her) in the shop – ‘Get your mucky hands off my ice-creams’ – to ‘Barking’ Barker our head teacher – ‘Look at my voice, Liam, I’m speaking to you!’

Dan was like a big friendly puppy, full of energy and bouncy. He always made us laugh a lot. Of the three of us I was the quietest, happy enough usually to go along with whatever the other two dreamed up. I just liked being with them. But I had my own very private reason, too, for going along with them. Anna.

Anna was Dan’s big sister, and I loved her. Simple as that. I loved her. I couldn’t tell her of course, because I was ten and she was fourteen. I didn’t love her just because she was beautiful, which she was (just the opposite in every way to big, lumpy Dan), but also because we talked – and I mean really talked – about things that really mattered, like books, like feelings, like oystercatchers. Liam and Dan were my mates, best mates, but Anna was my best friend and had been as long as I could remember.

I was finding it difficult to concentrate on my book. I kept regretting I hadn’t gone with them down to the quay. It was the sudden thought that it was Friday and that Anna might possibly be there, back for the weekend from secondary school on St Mary’s, that finally decided me. I would finish the book later.

I pulled on my wetsuit and ran down the sandy track through the farm to the quay. As I rounded the corner by the shed, I saw them all larking about on the quay. Anna was there. She’d already been in swimming, I could see that, but the other two hadn’t. They were standing on the edge, looking down into the water and hesitating.

The sea was murky and choppy and uninviting. I didn’t want to go in, not one bit, but Anna had seen me. I saw an opportunity to impress her, and just went for it. I charged down the quay going full pelt, screaming like a mad thing. Anna tried to wave me down but I ignored her.

I dodged past Dan, who was shouting at me to stop, sprang off and launched myself into the most spectacular swallow dive I could, the best dive of my life, just for her. I remember thinking that it seemed to be taking longer than it should to reach the water. After that I remember nothing.

CHAPTER 2

‘NOT A MUMMY MUMMY’

WHEN I CAME TO, I KNEW AT ONCE I WAS IN hospital. Nowhere else sounds or smells like a hospital. At first I thought that I was back visiting Gran in hospital in Truro, but then I realised that it was me lying there on a bed, not Gran. I couldn’t see where I was because there was a bandage round my eyes. I could feel it. In fact, most of my head seemed to be swathed in bandages. Someone was holding my hand and telling me not to worry, not to move. It was my mother. I wasn’t worried, but I was hurting. My whole head was heavy with pain.

‘What happened?’ I asked.

‘You’re fine, Bundle. You’re in hospital. You had an accident.’

‘What happened?’ I asked again.

‘You went in off the quay. But the water was too low. Your head hit a stone. You were lucky, Bundle. It could have been a lot worse.’ It felt bad enough to me.

‘You need water to dive into, Bun, you silly chump. Didn’t you know that?’ My father was there too, and his voice sounded strange, as if he’d been crying. Now I was worried. ‘Created quite a stir, you did,’ he went on. ‘Anna dragged you out of the sea, and gave you mouth-to-mouth. You’d have drowned else, and the boys went for help. We had the air ambulance in and they flew us straight here to Truro.’

‘You’ve broken your arm, and you’ve had a bit of an operation on your head,’ my mother was saying, ‘so you’ll have to stay in here for a few days. You sleep now.’

She didn’t have to tell me. I was already drifting away. I was in and out of sleep for days and nights, nearly a week they told me afterwards. My mother always seemed to be there when I woke up. Doctors and nurses came, to ask questions mostly and occasionally to examine my head. These were the only times the bandage came off – not that it made any difference, because my whole face was still so swollen that I couldn’t even open my eyes to see.

The doctors always seemed very pleased with me. I was making a good recovery. I wasn’t to worry they said. The swelling would go down in time and I’d be going home soon. I had visitors every day and my mother would always tell them the same thing, that I had had a very lucky escape, that I’d be fine.

I woke up one afternoon and heard my mother saying much the same thing, again. ‘He’ll be fine. But if it hadn’t been for you, Anna, there’d have been no lucky escape at all, and that’s the truth of it.’ Anna was there! In the room! She’d come to visit me. Oh God, how I wished I could see her.

‘And you two boys,’ my mother went on, sounding a bit weepy – it could only be Liam and Dan – ‘going for help like you did. You were wonderful, all of you, truly wonderful.’

I didn’t know what to say to any of them. I was overjoyed they were there, but somehow I couldn’t say it. Why is it that the most important things are so difficult to say? As it was I just pretended I was asleep under my bandages, and listened.

‘He’s sleeping now,’ my mother was saying. ‘But the doctors are sure he’ll be fine. Like I said, he’s lucky to be alive. You stay with him for a while, will you? I need to see the staff nurse. I shan’t be a moment.’ And I heard her go out.

For some moments no one spoke. Then Dan whispered, ‘With all those bandages, he looks like a mummy or something. Not a mummy mummy – an Egyptian tomb mummy, the haunting kind. You know what I mean.’ At that, I curled my hands into claws and then rose up, howling horribly. The giggling that followed was infectious. In the end all four of us were quite helpless with it. It made my head hurt, but I didn’t mind. I was just so happy, so relieved to be back with them.

‘I’ll come and see you again, Bun,’ Anna said as she left. ‘As often as I can.’

I cried behind my bandages when they left, but out of joy, not sadness. Anna had come to see me, and she’d be back. I’d be out of hospital and home in just a week, a couple at the most, that’s what they’d told me. Everything would be back to normal.

CHAPTER 3

INSIDE MY BLACK HOLE

THE NEXT DAY THE BANDAGES CAME OFF SO that the doctor could examine the wound on the side of my head. ‘Good, Bun, very good,’ said the doctor. ‘The swelling’s gone right down. You can open your eyes now.’

It took some doing – they felt a bit gummed up. But I did it. I opened them. The trouble was that I couldn’t see anything. I blinked and tried again. Blackness. Only blackness. I squeezed them tight shut, and opened them again. I felt I was deep inside a black hole, that there was no way out. I was drowning in blackness, unable to breathe, my heart pounding with sudden terror.

‘That looks a lot better, Bun,’ the doctor went on, turning my head with his cold hands, ‘a lot better.’

‘I can’t see,’ I told him. ‘I can’t see.’ There was a long silence. Then I could feel his breath on me, his face close to mine. He was lifting my eyelids.

‘What about now?’ he asked me. ‘Can you see a light? Can you see anything?’

‘No,’ I said.

‘What’s the matter with him, Doctor?’ My mother was asking just the question I wanted to ask, and she was frightened, really frightened. I could hear it in her voice.

‘Well, it’s a little difficult to say at this stage,’ the doctor said. ‘I expect it’s just a side effect of the trauma. He’s had a nasty crack on his head. It’ll correct itself in time, I’m sure. But we’ll do some tests. It’s nothing to worry about, Bun.’ His hand squeezed my shoulder. ‘You’ll be fine.’

If I had a pound for every time doctors told me that in the next few months, I’d be rich, extremely rich. But you can’t blame them. What else could they say? They had to try to reassure me. Everyone was trying to reassure me. When they discharged me and I got back home, it was the same old refrain: ‘Don’t worry, Bun. It’ll be fine.’

To begin with I believed them, because I wanted to believe them, needed to believe them. All the tests – and there were dozens and dozens of them, in Truro, in Bristol, in London – showed that I should be able to see. But the fact was that I couldn’t.

Every morning I opened my eyes hoping and praying, but no longer believing, that this time I’d be able to see something. I never could. Everything else had healed up long ago by now. The plaster was off my broken arm, and the stitches out of my head.

Dan said cheerily, that he preferred me when I’d looked like a mummy. Liam, I could feel, didn’t know what to say, so he said very little. He didn’t know how to include me, so he didn’t.

Only Anna didn’t pretend with me, didn’t feel awkward. She was just herself. She’d sit and talk, talk about anything and everything. She seemed to understand, without my having to tell her, what no one else did: that I felt lost, bewildered and frightened in a strange black world where I was entirely alone. She knew that I just wanted everyone to be normal, as they had been, so that I could still be part of the real world I remembered, their world.

My father was endlessly encouraging, taking me out on the fishing boat as he used to, trying to pretend my blindness didn’t exist. From time to time I’d hear my mother crying quietly downstairs, and I knew only too well why. But when she was with me she was always positive, always concerned and comforting and cuddly, more so than she ever had been, too much so.

No one ever spoke the word ‘blind’, not in my hearing anyway, either at home or in the various hospitals. So in the end I mentioned it myself, to Anna, because I knew she’d be honest with me. ‘I’m blind, aren’t I?’ I said to her, interrupting a story she was reading to me.

‘Yes,’ she replied quietly. ‘But because you’re blind now, it doesn’t mean you will be for ever, does it? I mean, your arm got better, so did your head. Why not your eyes?’

‘What if I stay blind?’ I asked her. ‘What if I don’t get better?’

‘It won’t change anything, not really. You’ll still be the same person. I’ll still be your friend. I always will be.’ I cried then as I’d never cried before, and Anna put her arm round me. It wasn’t exactly worth going blind to have her do that, but it comforted me as nothing else had; calmed my fears, made me feel less alone inside my black hole of despair.

CHAPTER 4

ONLY ONE WAY OUT

AFTER THAT, RESIGNATION GREW IN ME SLOWLY, imperceptibly. I would never see again. Never. There was to be no going back. I was going to have to live with myself as I was, sightless and alone, in permanent unending darkness. For a while I could think of nothing else and sank into a deep sadness, a bottomless pit of bitterness and self-pity. Anna tried to get me out of it, not by pitying me but by arguing with me.

‘It’s like a living death,’ I told her once.

‘You can’t say that,’ she said. ‘You know nothing about death. You haven’t been there and neither have I. We’re alive. All right, so you can’t see. But you can live. We’ve got to think about living.’

Anna came over to see me whenever she could, whenever she was home from school. More than anyone else she lightened my darkness. We’d talk of all the good times we’d had together and laugh about them. She brought me some of her CDs – Robbie Williams, Britney Spears, the Corrs – and some audio tapes as well –The Sword in the Stone, Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, and Arthur, High King of Britain. With their help I managed to banish the hateful silence of my room and to fill my life with sound. This seemed to help, to distract me, to take myself out of myself – at least, for a while. But as time went on I found I also had something else to worry about. I had tried to ignore it, to pretend it wasn’t so. But I couldn’t, not any longer.

At first I hoped it might be temporary, just a phase that would pass. But it didn’t pass. If anything it became worse. It was something I had to hide, something I’d told no one about, not even Anna. Ever since the accident I had been unable to remember things, little things that might not have mattered so much on their own. But there were also, I discovered, important parts of my life that had just gone missing. For instance, apparently we’d all been on holiday to Canada when I was five, to see my uncle Bill, my father’s brother, who lived in Toronto. People still talked about it. I remember I’d seen the photographs. It was the only time I’d been up in a jumbo jet. But I couldn’t remember any of it.

Nor could I recall anything of a trip up to London only a year or so ago, when we’d been to the zoo, and to the Science Museum, to the Tower of London, and to Stamford Bridge to see my favourite team Chelsea playing Tottenham Hotspur. All these events were a complete mystery to me. In fact, I had no memories of even being a Chelsea fan.

My mind, I was discovering, was full of blank spaces, gaps in my memory that were completely unpredictable, so that I was never prepared for them.

The vicar came to see me one day – ‘just to cheer you up,’ as he put it – and started going on about a production of Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat he’d put on the year before in the church, apparently.

‘You’ve a fine singing voice, Bun,’ he said. ‘Everyone said so. You were a wonderful Pharaoh, just wonderful.’

I didn’t have a clue what he was talking about. I had no memory of it whatsoever. I covered up as best I could, but how well I had covered up I could never really be sure, because of course I couldn’t see people’s faces to see how they reacted.

As each new memory gap became evident I became more and more terrified, because it made me fear I might now be losing my mind as well as my sight. It was my darkest, deepest secret and I kept it to myself.

There was even worse to come. It was becoming obvious that I couldn’t go back to school with the others on Tresco, that sooner or later I’d have to go to a ‘special’ school for the blind. There was no school for the blind on Scilly. I’d have to go to the mainland. I’d have to leave home.

When the time came my mother tried to break it to me as gently as she could. ‘All the kids have to go to school on the mainland at sixteen anyway, for their sixth form. You know that, Bundle. You’d just be doing the same thing, only a few years earlier, that’s all. And it’s just the right place for you. Dad and I have been to see it. They’ve got all the right equipment, all the specialist teachers you need. Lovely grounds, too. It’s only up at Exeter. Not far. We can come and see you, and you can come back home often. I promise.’

It was the final confirmation that I was indeed different from everyone around me and that, therefore, I was to be treated differently.

‘It won’t be until the end of the summer, Bun,’ said my father, laying a hand on my arm. ‘And it won’t be so bad, honest it won’t. You’ll see. I went away to school at your age, and I loved it. Lots to do, lots of new friends.’

I was to be separated from home, from everyone I knew and loved, my mother, my father, from Liam and Dan, and from Anna, too. It was more than I could bear. I lay there all night thinking it through. By the time I heard the dawn chorus of gulls and oystercatchers, I had made up my mind.

There was only one way out, and I would have to take it.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.